ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

A study was conducted on ‘Escherichia coli’ to reveal its presence in poultry and poultry environment in Jammu (India). A total of 200 samples (90 of poultry droppings, 45 waterers, 40 feeders and 25 poultry handlers) were processed, of which 148 samples yielded E. coli isolates. The isolation rate of E. coli from poultry droppings was 92.22% while from poultry environment was 59%. The 148 isolates of E. coli were further characterized by performing multiplex polymerase chain reaction for the genes, stx1, stx2, eaeA and ehxA. 16 of 148 (10.81%) of isolates were carrying the virulence genes. Out of them 13 isolates were from poultry and three isolates were obtained from waterers. Thirteen isolates from poultry droppings were positive for virulence genes, eight (61.5%) harbored eaeA gene, while four harbored stx2 and eaeA, both. One of the isolate demonstrated the presence of stx2 gene, alone. A total of three out of 36 isolates from waterers revealed the presence of eaeA gene. All the isolates were negative for the ehxA gene. Also, none of the isolate from poultry feed or poultry handlers carried virulence genes. The antibiotic sensitivity assay of isolates was done against 11 antibiotics commonly practiced in poultry medicine revealed maximum resistance to Enrofloxacin (100%), followed by Cefotaxime (91.89%), while maximum sensitivity was noted to Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid (95.27%).

Escherichia coli, Virulence Genes, Multiplex PCR, Environment, AMR

The Escherichia coli is a normal intestinal flora of humans and warm-blooded animals. Some strains are pathogenic and some strains of E. coli transfer plasmid DNA responsible for enterotoxin or invasive factors.1 However, the bacterium has been implicated in the etiology of many diarrhoeal diseases and systemic infections in animals and humans.2 In poultry E. coli are responsible for causing many infections including swollen head syndrome, omphalitis (yolk sac infection), and colibacillosis.3 The E. coli possesses several pathogenic determinants, such as shiga-like toxins encoded by genes stx1 and stx2 and also these toxins are referred as verotoxins; intimin encoded by eaeA gene and entrohemolysins encoded by ehxA gene.4 Shiga-like toxins are the phage encoded toxins responsible for causing serious disease conditions especially in immunocompromised humans and children.5 Intimin (virulence – associated factor) helps in the attachment of the bacterium to epithelial cells of intestines, there by producing attaching and effacing lesions in the intestinal mucosa.6 Intimin encode by eaeA is a chromosomal gene which resides in the pathogenicity island called as locus for enterocyte effacement. Another virulence determinant enterohemolysin encode by ehxA7 is found in some strains of organism alone or in combination with other genes. These pathogenic E. coli have been found associated with number of disease conditions as endocarditis, meningitis, septicemia, urinary tract infections and diarrhea in human beings.8

The presence of E. coli in foods of animal origin indicates contamination and may lead to the food spoilage in addition to causing various foodborne outbreaks, especially when such bacteria acquire drug resistance determinants by different mechanisms.9 The transmission of pathogenic strains of E. coli to man could occur not only through poultry meat and meat products but also from their environment due to unhygienic conditions prevailing at the processing sites.10 Further water and green vegetables that are contaminated by the feces of carriers have also been implicated in the spread of bacterium.11

Faecal contamination of poultry farm environment supports’ re-infection of birds and therefore, persistence of the pathogens in the farm. Hence poultry production units represent a major reservoir for the E. coli and human infections can occur via faecal contamination of food products with poultry/other livestock wastes and slurries.12,13 Therefore, to reduce the risk of human infections, it is critical to prevent bacterial population in live birds at the primary production site and finally elimination from the food chain. In comparison to the other developed countries, poultry farming in the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir is a house hold practice. To generate the data on the occurrence of multidrug-resistant E. coli, possessing the pathogenic genetic markers from poultry and poultry environment will play a significant role in identification of niche areas and thereby in controlling the emerging foodborne pathogen from important lively hood sources of the area. Such studies are poorly conducted in this Union Territory and antibiotic resistance in bacteria is a global threat. So keeping in view the significance and public health importance this study was conducted.

Two hundred samples from 23 different poultry farms of the Jammu district were collected. The samples collected were from poultry birds and from poultry environment. The samples from poultry birds included faecal material (90 samples) while the samples from poultry environment included those from the waterers (45 samples), feeders (40 samples) and swab from poultry workers (25 samples). The samples were aseptically collected and transported to the laboratory maintaining the refrigeration conditions with ice packs and processed in the division of veterinary public health and epidemiology.

Research involved poultry droppings and poultry environment samples. The study adheres to the approval of the advisory committee and the informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrolling in the study.

For the isolation of E. coli, samples first inoculated on the MacConkey’s agar plates (HiMedia Pvt. Ltd., India) and incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C. Colonies showing the pink colour were selected and further inoculated on the Eosin Methylene Blue agar (EMB) (HiMedia Pvt. Ltd., India). Colonies exhibiting the characteristic greenish gold metallic sheen were further cultured on nutrient agar slants and further confirmed as per the standard microbiological techniques.14

Bacterial DNA extraction

Extracted the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) of bacteria by snap chill technique. By suspending a loop of bacterial culture in 500 µl sterile distilled water in a 2 ml microcentrifuge tube. Boiled the tube for 10 minutes in a water bath, followed by chilling on ice and centrifugation at 10000 g for 5 minutes. 2.0 µl of supernatant was used as template DNA for mPCR.

Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction for detecting the virulence genes

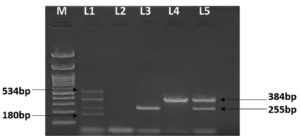

The presence of the virulence genes viz. eaeA, ehxA, stx1 and stx2 were detected by multiplex PCR as described previously with slight modifications.4 The polymerase chain reaction was constituted in a volume of 25 µl by adding 12.5 µl of (master mixture) IX Green GoTag Flexi buffer (Promega Pvt. Ltd.), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each 2′-deoxynucloside 5′-triphosphate (dNTPs), 0.5 mM of each forward and reverse primer (Table 1), Tag polymerase 1 unit (Promega) and 2.0 µl DNA template. The samples in the beginning subjected to denaturation at 95 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 15 cycles, each cycle consisting of denaturation at 95 °C for 1 minute, annealing at 65 °C for 1 minute and elongation at 72 °C for 1.5 minutes. A 2nd phase of twenty cycles was performed with each cycle consisting of denaturation of one minute at 95 °C, annealing at 60 °C for two minutes, extension for two minutes at 72 °C, final extension was done at 72 °C for 5 minutes. The PCR product was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis for amplicon sizes of 180 bp, 255 bp, 384 bp and 534 bp for stx1, stx2, eaeA and ehxA genes respectively by using 1.5% agarose gel containing 0.5 µg/ml ethidium bromide15 and visualized under ultraviolet light in a gel documentation system (Bio-rad).

Table (1):

List of Primers (5′-3′) used in the multiplex PCR

| Primer | Sequence | Amplicon size |

|---|---|---|

| stx1-F | ATAAATCGCCATTCGTTGACTAC | 180 bp |

| stx1-R | AGAACGCCCACTGAGATCATC | |

| stx2-F | GGCACTGTCTGAAACTGCTCC | 255 bp |

| stx2-R | TCGCCAGTTATCTGACATTCTG | |

| eaeA-F | GACCCGGCACAAGCATAAGC | 384 bp |

| eaeA-R | CCACCTGCAGCAACAAGAGG | |

| ehxA-F | GCATCATCAAGCGTACGTTCC | 534 bp |

| ehxA-R | AATGAGCCAAGCTGGTTAAGCT |

Antibiotic sensitivity assay

All the Escherichia coli isolates obtained in the present research work were tested against the eleven commonly used antibiotics in poultry practice at the farms. The sensitivity assay was carried out by using the Muller Hinton Agar plates by the disc diffusion method as described previously.16 The susceptibility/resistance patterns of bacteria against the antibiotics viz. Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid, Chloramphenicol, Cefotaxime, Ciprofloxacin, Enrofloxacin, Polymixin B, Tetracycline, Doxycycline HCl, Norfloxacin, Nalidixic acid and Sulphadiazine, was determined. The bacterial strains were designated as sensitive, intermediate or resistant to an antibiotic, based on the diameter of zone of inhibition interpreted as per CLSI guidelines.17

The isolates exhibiting characteristic pink colonies on MacConkey’s Lactose agar (MLA) and greenish golden metallic sheen on Eosin Methylene Blue Agar were recognized as E. coli and further confirmed based on Gram staining coupled with the biochemical profile of the isolates. The 148 isolates obtained on processing 200 samples were confirmed by the standard microbiological procedures.14

Out of 148 isolates, 83 were from poultry droppings, 36 were from waterers, 21 were from feeders and eight were from hand swab samples taken from poultry workers. The detail of isolates from different samples is given in Table 2.

Table (2):

Occurrence of E. coli from Poultry and Poultry Environment

No. |

Type of samples |

Sample analysed |

E. coli isolate |

Occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Poultry droppings |

90 |

83 |

92.22% |

2 |

Water (waterers) |

45 |

36 |

71.11% |

3 |

Feed (feeders) |

40 |

21 |

52.50% |

4 |

Hand swab from workers |

25 |

08 |

32.00% |

Total |

200 |

148 |

74.00% |

Detection of pathogenic genes by Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction

All the 148 isolates obtained were screened for the presence of genes viz. stx1, stx2, eaeA and ehxA by using, 180 bp, 255 bp, 384 bp and 534 bp primers respectively. Out of them 16 strains were found to carry virulence gene. From the 83 strains from poultry droppings, 13 were positive for one or more genes alone or in combination. 12 of the 13 isolates from poultry droppings harboured eaeA gene, and one isolate harboured stx2 gene, while four were having both stx2 and eaeA gene (Figure). None of the isolate from poultry droppings revealed stx1 gene or ehxA gene.

Figure. Multiplex PCR presenting the genes stx1, stx2, eaeA, and ehxA of E. coli isolated from poultry and poultry environment. Lane M is showing 100 bp marker, Lane L1 shows positive control, revealing all four genes, viz. stx1, stx2, eaeA, and ehxA having the amplicon size of 180 bp, 255 bp, 384 bp, 534 bp respectively. Lane L2 is negative control while lane L3 shows presence of stx2 (255 bp), lane L4, shows eaeA (384 bp) while lane 5 demonstrates presence of stx2 (255 bp) coupled with eaeA (384 bp)

Out of 65 isolates from poultry environment, only three isolates (all from water samples) revealed virulence gene eaeA. None of the Escherichia coli species from poultry environment revealed stx1, stx2, or ehxA gene. The detail of all these four genes viz. stx1, stx2, eaeA, and ehxA have been presented in Table 3.

Table (3):

Profile of virulence genes of Escherichia coli

| Sample | No. of Isolates | E. coli virulence genes screened | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stx1 | stx2 | eaeA | ehxA | |||

| Poultry | Poultry feces | 01 | – | + | – | – |

| 04 | – | + | + | – | ||

| 08 | – | – | + | – | ||

| Poultry environment | Water | 03 | – | – | + | – |

| Feed | 00 | – | – | – | – | |

| Poultry workers (hand swabs) | 00 | – | – | – | – | |

| Total | 16 | – | 05 | 15 | – | |

Antibiotic sensitivity assay

The antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Escherichia coli obtained in the study revealed maximum resistance to Enrofloxacin (100% – all isolates were resistant), followed by Cefotaxime (91.89% – 136 isolates resistant), Nalidixic acid (58.79% – 87 resistant isolates), Norfloxacin (56.76% – 84 resistant isolates), Tetracycline 52.03% – 77 isolates resistant), Ciprofloxacin (43.92% – 65 isolates resistant), and sulphadiazine 39.86% – 59 isolates resistant). Maximum sensitivity of E. coli isolates from poultry was noted against Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid 95.27% – 141 isolates sensitive), Chloramphenicol 83.79% – 124 isolates sensitive), Polymixin B 75.68% – 112 isolates sensitive), Doxycycline hydrochloride 64.86% – 96 isolates sensitive). The detail of each of the antibiotic, sensitivity/resistance pattern is explained in the Table 4.

Table (4):

Phenotypic profile of Escherichia coli obtained from poultry and poultry environment against 11 commonly used antibiotics in farms

No. |

Antibiotic |

Abbreviation |

Disc content (in µg) |

Sensitive isolates |

Resistant isolates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid |

AMC |

30 |

(141) 95.27% |

(07) 04.73% |

2 |

Tetracycline |

TE |

30 |

(71) 47.97% |

(77) 52.03% |

3 |

Chloramphenicol |

C |

30 |

(124) 83.79% |

(24) 16.21% |

4 |

Cefotaxime |

CTX |

30 |

(12) 08.11% |

(136) 91.89% |

5 |

Polymyxin B |

PB |

300 Units/disc |

(112) 75.68% |

(36) 24.32% |

6 |

Sulphadiazine |

SZ |

100 |

(89) 60.14% |

(59) 39.86 % |

7 |

Ciprofloxacin |

CIP |

5 |

(83) 56.08% |

(65) 43.92% |

8 |

Doxycycline hydrochloride |

DO |

30 |

(96) 64.86% |

(52) 35.13% |

9 |

Enrofloxacin |

EX |

10 |

0% |

(148) 100% |

10 |

Nalidixic acid |

NA |

30 |

(61) 41.21% |

(87) 58.79% |

11 |

Norfloxacin |

NX |

10 |

(64) 43.24% |

(84) 56.76% |

Escherichia coli are the foodborne pathogen, usually transmitted through the contaminated foods or water among the animals, birds and human beings.10 The E. coli are extremely diverse, with commensal and pathogenic strains coexisting in nature. In the present study, a total of 23 poultry farms in and around Jammu were studied and 200 samples from poultry and poultry environment were collected.14 The samples included poultry droppings, as well as samples from waterers, feeders, and poultry handler swabs. Out of 200 samples, 90 samples were from poultry droppings, while 110 samples were collected from poultry environment. The isolation rate of Escherichia coli from poultry droppings was 92.22%. (83 isolates from 90 samples), while from poultry environment the isolation rate was 59% (65 isolates from 110 samples). Isolation rate of E. coli from waters was 71.11% (36 isolates from 45 samples), from feeders was 52.5% (21 isolates from 40 samples), containers used for providing water to birds from swabs samples collected from handlers was 32% (08 isolates from 25 samples). All the 148 E. coli isolates were screened for presence of multiple virulence genes. 16 of 148 (10.81%) of the isolates revealed one or more gene, among stx1, stx2, eaeA, and ehxA gene. The presence of virulence genes in this study was slightly lower in comparison to a study conducted at Andhra Pradesh (India), where a prevalence rate of 12% was reported.18 A total of 13 of 16 (81.25%) from dropping revealed virulence gene, while three isolates carrying the virulence genes were isolated from waterers. Out of 13 isolates from poultry 8 (61.5%) harboured eaeA gene. Thus in all a total of 11 of 16 (68.75%) carried eaeA. Four isolates carried eaeA in association with stx2 (25%), and only one isolate (6.25%) harbored stx2 gene alone. No isolate revealed the presence of stx1 and ehxA gene. Thus the overall presence of virulent genes, stx1, stx2, eaeA and ehxA was 0% (00/16), 31.75% (5/16), 68.75% (11/16) and 0% (00/16), respectively. In previous study on E. coli isolates from samples collected from chicken and free flying pigeon in Kashmir (India), eaeA gene was also more prevalent (2.34%), followed by hlyA (1.64%), while 1.4% isolates harbored both eaeA and hlyA gens.19 All isolates with the eaeA gene but no stx1 or stx2 gene were classified as EPEC, whereas, isolates with stx1 or stx2 or both genes but no eaeA were classified as STEC. As 11 of 16 (68.75%) isolates carrying the virulence gene harboured eaeA gene alone, and was identified as EPEC. 4 of 16 (25%) harboured stx2 genes while none of the isolate carried stx1 or ehxA gene.

The E. coli is one of the seven, antimicrobial resistant bacteria identified by WHO and act as a sentinel organism for the evolution of antimicrobial resistance. The indiscriminate and extensive use of antimicrobials in the field led the development of drug resistance against number of antibiotics. Many of the antibiotics have lost their potency due to the establishment of drug resistance strains as a result of continuous indiscriminate use of antibiotics in poultry and other animals.20 However, the resistance to antibiotics is being frequently reported in different bacteria, jeopardizing the efficacy of antimicrobial medications. Antimicrobial resistance in bacteria colonizing intestines is gaining importance because gut is a complex and cohesively inhabited habitat of bacteria where antibiotic resistant organisms can horizontally transmit resistance genes to others. Antibiotic usage in animal husbandry is also being recognized as a worldwide health issue, both in terms of poultry/animal health and welfare and due to the development of resistant bacteria.

All the E. coli bacterial isolates obtained in the present study were screened against the eleven commonly used antibiotics in poultry medicine. The isolates demonstrated maximum sensitivity to Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid (95.27%), followed by Chloramphenicol (83.79%), while maximum resistance was observed against Enrofloxacin (100%).

E. coli occurrence was found highest in fecal matter followed by birds waterer, Feeder, and hand wash of poultry workers. Presence of E. coli, in hand wash samples reflects unhygienic practices of workers and contamination from poultry environment predicting alarming situations and easy passage of resistant gene factors. However, presence of STEC genes producing E. coli in poultry and poultry environment from Jammu district was found low. As per the data collected during the research study on antimicrobial usage in the poultry sector in the Jammu district was found coherent with the antibiotic resistance of isolates obtained from samples.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful to Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Jammu for providing necessary facilities to conduct the study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

This study was funded by Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Jammu, sanctioned by the research committee, communicated by Director Research, vide his office no. AUJ/DR/21-22/F-50/587-628, dated: 07-06-2021.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Dean FVSc & AH, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Jammu- vide his office No. AUJ/FVSJ/21-22/PF/261-63, dated 06/09/2021.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrolling in the study.

- Makvana S, Krilov LR. Escherichia coli Infections. Pediatr Rev. 2015;36(4):167-70.

Crossref - Buxton A, Fraser G. Animal Microbiology. Escherichia coli. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, London, Edinburg, Melbourne. 1977;1:94-102.

- Gross WB. Diseases due to Escherichia coli in poultry, Escherichia coli in domesticated animals and humans. Wallingford, U.K. Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International. 1994;1:237-259.

- Paton AW, Paton JC. Detection and Characterization of Shiga Toxigenic Escherichia coli by Using Multiplex PCR Assays for stx1 , stx2 , eaeA , Enterohemorrhagic E. coli hlyA, rfbO111 , and rfbO157. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(2):598-602.

Crossref - Jourdan-da Silva N, Watrin M, Weill FX, et al. Outbreak of Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome due to Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia Coli O104;114 among French Tourists Returning from Turkey. European Centre for Prevention and Control. 2012;17(4):20063.

Crossref - Jerse AE, Yu J, Tall BD, Kaper JB. A genetic locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli necessary for the production of attaching and effacing lesions on tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(20):7839-7843.

Crossref - Schmidt H, Beutin L and Karch H. Molecular analysis of the plasmid-encoded hemolysin of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL 933. Infect Immun. 1995;63(3):1055-1061.

Crossref - Daini OA, Ogbulo OD, Ogunledun A. Quinolones Resistance and R-plasmids of some gram-negative enteric Bacilli. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2005;6(1):14-19.

Crossref - Donnenberg MS, Whittam TS. Pathogenesis and evolution of virulence in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(5):539-548.

Crossref - Rashid M, Kotwal SK, Malik MA, Singh M. Prevalence, genetic profile of virulence determinants and multidrug resistance of Escherichia coli isolates from foods of animal origin, Vet World. 2013;6(3):139-142.

Crossref - Hui YH, Sattar SA, Murrell KD, Nip W-K, eds. Foodborne Disease Handbook. 2nd ed. Revised and Expanded. Vol 2: Viruses, Parasites, Pathogens, and HACCP. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 2001.

- Mainil JG, Daube G. Verotoxigenic Escherichia coli from animals, humans and foods:who’s who? J Appl Microbiol. 2005;98(6):1332-1344.

Crossref - Fairbrother JM, Nadeau E. Escherichia coli:on-farm contamination of animals. Rev Sci Tech. 2006;25(2):555-69.

- Cruickshank R, Duguid JP, Marmion BP, Swain RHA. (eds.). Medical Microbiology, 12th Ed. Volume –II. 1975:428-434.

- Smith SB, Aldridge PK, Callis JB. Observation of individual DNA molecules undergoing gel electrophoresis. Science. 1989;243:203–206.

Crossref - Bauer AW, Kirby WMM, Sherris JC, Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disc method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;36:493-496.

- CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing:20th informational supplement, CLSI document M100-S20. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. 2010.

- Sekhar MS, Sharif NM, Rao TS, Metta M. Genotyping of virulent Escherichia coli obtained from poultry and poultry farm workers using enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus-polymerase chain reaction. Vet world. 2017;10(11):1292-1296.

Crossref - Wani SA, Samanta I, Bhat MA, Nishikawa Y. Investigation of Shiga toxin- producing Escherichia coliin avian species in India. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2004;39(5):389-394.

Crossref - White DG, Zhao S, Simjee S, Wagner DD, McDermott PF. Antimicrobial resistance of foodborne pathogens. Microbes Infect. 2002;4(4):405-412.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.