ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

The World Health Organization (WHO) recorded an estimated 263 million malaria cases globally in 2023, leading to about 597,000 mortalities. Most of this burden occurred in the WHO African Region, which accounted for approximately 94% of cases and 95% of malaria-related deaths. Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) remain the mainstay of malaria treatment globally; however, the emergence of Plasmodium falciparum resistance compromises their sustained efficacy. Although mutations in the Plasmodium falciparum Kelch 13 (Pfk13) propeller domain are largely proven to be markers of partial artemisinin resistance, greater focus has turned to Plasmodium falciparum Adenosine Triphosphatase 6 (PfATPase6) as a potential supplementary determinant. This review compiled evidence from published articles between 2015 and 2025, sourced from Google Scholar, PubMed, ProQuest, and ScienceDirect, with a focus on PfATPase6 polymorphisms, their distribution, functional role, detection techniques, and implications for malaria prevention. Notable nonsynonymous single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) such as E431K, S769N, A623E, S769M, and M699V have been reported spanning Asia, the Americas, and Africa. Several studies reveal a correlation with decreased in vitro susceptibility or enhanced artemether Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50), although findings are inconsistent due to interrelated resistance markers, environmental differences, and deviations in methodology. Recent improvements in molecular monitoring techniques, like next-generation sequencing, high-resolution melting analysis, and advanced real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques, have broadened the ability to detect uncommon variants and have reinforced surveillance systems. Despite inconsistency in findings, there is evidence that PfATPase6 reduces sensitivity to artemisinin; therefore, it should be taken into consideration in resistance surveillance schemes. It is recommended to incorporate PfATPase6 genotyping alongside Pfk13 surveillance and treatment efficacy studies to offer more insights into the emergence of resistance. These approaches are vital to expound the underexplored role of the PfATPase6 in resistance patterns and encourage the sustainability of antimalarial drugs.

Malaria, Resistance, PfATPase6, Artemisinin, Plasmodium falciparum, Mutations

Malaria is a significant public health threat, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions, caused by Plasmodium falciparum, which can be transmitted via the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito.1 While the genus “Plasmodium” encompasses numerous species, five are associated with human malaria: Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium knowlesi, and Plasmodium falciparum. The deadliest among the species is Plasmodium falciparum, which predominates in Sub-Saharan Africa.2 According to the World Malaria Report 2024, an estimated 263 million malaria cases were recorded globally in 2023, leading to about 597,000 mortalities. Most of this burden occurred in the World Health Organization (WHO) African Region, which accounted for approximately 94% of cases and 95% of malaria-related deaths. Nigeria solely contributed approximately 68 million cases (26% of the worldwide total) and 30.9% of global mortalities, emphasizing the country’s major role in the malaria landscape, globally.3 This constant high burden reinforces the urgent demand for continual surveillance and significant advancement in effective control tactics.

The use of artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) has revolutionized malaria treatment, providing effective alternatives against Plasmodium falciparum infections.3 Artemisinin, obtained from Artemisia annua (a sweet wormwood plant), exhibits rapid action against Plasmodium falciparum and is often administered in combination with other partner drugs to enhance efficacy and reduce the risk of emerging resistance.4 Given the rising incidence of resistance to older antimalarial medications, such as sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and Chloroquine, reported from various regions, artemisinin and its derivatives have consistently gained prominence as an alternative drug.5,6 Artemisinin combination therapy, which consists of artemisinin (ART) in combination with one or more other antimalarial medications known as partner therapies, is currently used as the first and second-line treatment for malaria in most endemic countries.7,8 Six ACTs are currently recommended by the WHO for treating malaria cases worldwide: Artemether + Lumefantrine, Artesunate + Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine, Artesunate + Amodiaquine, Artesunate + Mefloquine, Dihydroartemisinin + Piperaquine, and Artesunate + Pyronaridine.9

Although the increasing emergence of resistance to artemisinin and its partner drugs threatens these benefits.9 Resistance has been documented majorly in Southeast Asia and, more recently, in numerous African nations, highlighting issues regarding the long-lasting sustainability of an apostrophe to the ACT potency.10 To ensure treatment outcomes and develop efficient surveillance systems, it is pivotal to comprehend the molecular mechanisms driving artemisinin resistance.

Among the implicated genetic factors in artemisinin resistance, the Plasmodium falciparum Adenosine Triphosphatase 6 (PfATPase6) gene has garnered attention because of its function in calcium homeostasis within the parasite.10 It encodes a protein that is an ortholog of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) located in Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of the deadliest form of malaria.11 This protein maintains calcium homeostasis, which depends on several cellular functions, such as muscle contraction and signal transduction. There is cognition that this PfATPase6 is the target of artemisinin and its derivatives, which hamper calcium transport and eventually lead to the parasites’ cell death.4 Recent studies have shown that the interaction of artemisinin with PfATPase6 is through hydrophobic interactions, specifically affecting protein conformation. Notably, mutations in this gene could alter its structure, resulting in target site alteration and decreasing drug binding affinity.12 An in silico study revealed that specific mutations, including L263D, L263E, and L263K, could impact the PfATPase6 structure and reduce the artemisinin’s binding affinity.13 Understanding the impact of mutations in the PfATPase6 gene on treatment outcomes is pivotal for optimizing malaria control approaches and continually ensuring ACTs’ effectiveness.

Although Plasmodium falciparum Kelch 13 (PfK13) mutations have been thoroughly investigated, the role of the PfATPase6 gene mutations in artemisinin resistance is still negotiable and little understood. This study summarizes emerging information to determine if PfATPase6 mutations are a valid secondary molecular indicator of resistance, especially in African regions where traditional PfK13 mutations are almost absent.

Published articles on malaria, antimalarial drug resistance, PfATPase6 gene, and Plasmodium falciparum resistance to antimalarial drugs were obtained from Science Direct, ProQuest, PubMed, and Google Scholar within the range of 2015-2024. Relevant articles with keywords on Malaria, Resistance, PfATPase6, Artemisinin, and Plasmodium falciparum were retrieved for review. Papers featuring Plasmodium falciparum without significant data on the PfATPase6 gene and resistance to artemisinin were excluded from the study.

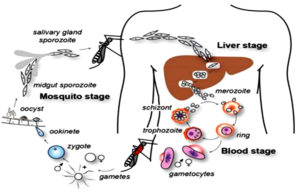

Life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum

Humans are the intermediate hosts where asexual reproduction occurs, but Anopheles mosquitoes are the definitive hosts that harbor the sexual reproduction stage.14 In humans, parasitic infection starts following a bite from an infected female Anopheles mosquito.15 Out of 460 Anopheles mosquito species, reports suggest that over 70 transmit falciparum malaria.16 Among the most well-known and common vectors, Anopheles gambiae is predominant in Africa.17 The mosquito uses its proboscis to pierce the skin during feeding, releasing the infectious stage (sporozoite) from its salivary glands.17 The saliva of mosquitoes contains anti-inflammatory and anti-hemostatic enzymes that prevent blood clotting and suppress the pain response.16 Usually, there are 20-200 sporozoites in each infected bite, but a few sporozoites invade the hepatocytes.18

The actin and myosin proteins under their plasma membrane work as a motor to propel the sporozoites as they glide through the bloodstream. After entering the hepatocytes, the parasite becomes a trophozoite, losing its surface coat and apical complex.19

Hepatocytes undergo 13-14 rounds of mitosis to produce schizonts, which are syncytial cells (coenocytes) that reside inside the parasitophorous vacuole. This process is known as schizogony.16 The surface of the schizont produces thousands of haploid (1n) daughter cells, called merozoites, from tens of schizont nuclei. In the liver stage, up to 90,000 merozoites can be produced, which are then released into the bloodstream as merosomes, which are parasite-filled vesicles.

The apicomplexan invasion organelles (pellicle, apical complex, and surface coat) are used by merozoites to recognize and enter the host erythrocyte (red blood cell).20 Initially, the merozoites attach themselves randomly to the erythrocyte. After that, it reorients so that the erythrocyte membrane is close to the apical complex. The parasite can grow inside the erythrocyte by forming a parasitophorous vacuole.21 Almost every parasite in the blood is in the same stage of growth during this infection cycle, which occurs in a highly coordinated manner.22 The circadian cycle of the human host is necessary for this exact timing mechanism to function.

Haemoglobin digestion is essential for parasite metabolism within the erythrocyte.23

Anemia, fever, and neurological disorders are among the clinical presentations of malaria that manifest throughout the blood stage.24 In Addition, the parasite changes its erythrocytic shape by producing knobs on the membrane.25 The liver, brain, and heart are only a few human tissues or organs where infected erythrocytes are frequently seen. This is because proteins on the erythrocyte membrane derived from parasites attach to receptors in human cells.22

Cerebral malaria is a highly critical form of disease that is caused by sequestration in the brain and raises the risk of mortality for the victim.22

Following erythrocyte invasion, the parasite differentiates into a spherical trophozoite inside a parasitophorous vacuole and loses its unique invasion organelles, surface coat, and apical complex.23 By breaking down the proteins in the erythrocyte’s hemoglobin, the trophozoite transforms the leftover heme into insoluble, chemically inert β-hematin crystals known as hemozoin.23

The parasite divides asynchronously into several mitotic divisions and replicates its Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) several times during the schizont stage.24 The term erythrocytic schizogony refers to dividing and multiplying cells within the erythrocyte.25 The schizonts generate 16-18 merozoites each, and the merozoites cause red blood cell rupture.26 The released merozoites infiltrate newly formed erythrocytes, but before a free merozoite enters another erythrocyte, it spends around 60 seconds in the bloodstream. It takes about 48 hours to complete one erythrocytic schizogony. As a result, the infected erythrocytes rupture simultaneously, which leads to the typical clinical signs of falciparum malaria, including fever and chills.25 Certain merozoites undergo sexual differentiation to become gametocytes, either male or female. Approximately 7 to 15 days are needed for these gametocytes to grow fully during gametocytogenesis, releasing sporozoites to complete the lifecycle.27 A female Anopheles mosquito subsequently consumes these during a blood meal to begin another cycle. The life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum is presented in Figure 1.

Molecular Basis of Antimalarial Drug Resistance in Plasmodium falciparum

Resistance to antimalarial drugs is a significant threat to controlling and eradicating malaria.28 Malaria resistance is notably exhibited by Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax, which have been reported by many studies indicating their resistance to antimalarial medications.29 The primary mechanism underlying the development of this phenotype is the mutation of drug resistant genes or an increase in the number of copies of those genes.30 Plasmodium falciparum’s resistance to antimalarial medications has been demonstrated in most of the classes of antimalarials, including quinolines, antifolates, and ART derivatives.31 According to the WHO, drug resistance refers to the ability of a parasite to survive and persist despite exposure to a drug and its toxic effects, even when the drug is present at adequate levels at the site of action. Antimalarial drug resistance emergence depends on the parasites’ genetic makeup, with gene amplification or mutations that confer reduced susceptibility.32 Changes in the quantity, structure, or composition of proteins cause resistance to drugs in organisms.33 Gene amplification and SNPs are the two forms of genetic alteration that mediate the protein change.34 Antimalarial resistance is currently a significant hindrance to disease control; hence, researchers are always looking for solutions. Since there is no guarantee that resistant parasite strains won’t emerge, new compounds must constantly be developed; innovative drugs with unique modes of action are currently undergoing clinical trials.33

Resistance to currently available antimalarial drugs can arise for a few reasons. It is also important to take into consideration factors such as the total parasite load, the rate of drug effectiveness, drug compliance, and inadequate adherence to the malaria treatment protocol.33 Misuse of medications, poor pharmacokinetic characteristics, and improper dosing result in insufficient drug exposure to parasites.35 The danger of hyper-parasitemia, recrudescence, and hyper-gametocytaemia is enhanced by low-quality or fabricated antimalarials that lack active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), which can encourage resistance. The genes Pfnhe1, Pfmdr1, Pfmrp, Pfdhps, Pfk13, Pfdhfr, Pfcrt, and PfATPase6 are associated with antimalarial drug resistance.36 Identifying the molecular markers linked to resistance in the laboratory is essential to sustain the efficacy of the current antimalarial drugs. The molecular markers that are often implicated in antimalarial drug resistance are shown in Table 1.

Table (1):

Molecular markers that are commonly associated with antimalarial drug resistance

Genes |

Notable Mutations |

Chromosomal Locations |

Class of Antimalarials associated with resistance |

Phenotypic Effect |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pfcrt |

K76T, C72SN326S, A220SI356T |

Chromosome 7 |

Chloroquine and Amodiaquine |

Resistance to Chloroquine, Reduction in drug accumulation in the food vacuole |

35-37 |

Pfmdr1 |

N86Y, D1246YY184F, N1042D |

Chromosome 5 |

Amodiaquine, Chloroquine, Mefloquine, Lumefantrine, |

Regulation of the potency of ACT partner drugs Multiple drug transport modification |

36,37 |

Pfdhfr |

N51I, I164LC59R, S108N |

Chromosome 4 |

Cycloguani Pyrimethamine, |

Sulfadoxine-Pyrimethamine resistance Decreased binding to antifolate drugs |

36,38 |

Pfcytb |

Y268C, Y268SY268N |

Mitochondrial genome |

Atovaquone |

Increase in atovaquone EC50/clinical therapeutic failure Altered binding of atovaquone |

32,39 |

Pfnhe-1 |

Repeat polymorphisms (DNNND) |

Chromosome 13 |

Quinine |

Decreased susceptibility (higher IC50 for quinine) |

32,40 |

PfATPase4 |

P990R, G358SD1116G, D1116N398F, 917L, 211T, 415D |

Chromosome 12 |

Pyrazoles, Dihydroisoquinolones |

Decreased affinity for Naz, a High increase in IC50 to medications targeting PfATP4 |

38,41 |

PfATPase6 |

L263E, A623E, S769N, E431K |

Chromosome 1 |

Artemisinin and its derivatives |

Decreased susceptibility Potential altered Ca²+ homeostasis |

11 |

Pfk13 |

C580Y, R539TI543T, Y493HF446I, P553LM476I, N458Y |

Chromosome 13 |

Artemisinin and its derivatives |

Ring stage tolerance Delayed parasite clearance |

39,41,42 |

Pfpm2 |

Copy Number Variation (CNV); Increased copy number |

Chromosome 14 |

Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine |

Higher rates of treatment failures decreased vulnerability in piperaquine survival assays |

40,43 |

Mechanisms of action of artemisinin

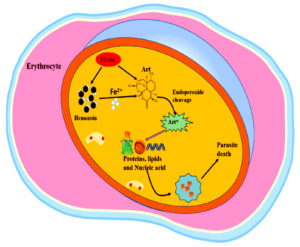

The mode of action of artemisinin against Plasmodium falciparum involves the destruction of proteins by carbon-centered radicals released upon activation of the drug. Artemisinin produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) when ferrous iron (Fe2+) is activated during hemoglobin digestion, as shown in Figure 2. This activation results in the development of alkylating agents that disrupt vital biomolecules, lipids, and proteins, damaging cellular roles and causing the death of parasites.42 This action radically differs from Other antimalarial medications, which usually target one enzyme or pathway.

Recent studies proposed a direct interaction between Artemisinin and PfATPase6, a calcium ATPase essential for maintaining calcium homeostasis in Plasmodium falciparum.32 The binding of artemisinin to PfATPase6 causes notable structural changes that impair its role, resulting in elevated levels of calcium intracellularly and, ultimately, cell death.43 Emerging evidence shows that derivatives of Artemisinin could target Mitochondrial roles within the parasite, disrupting vital metabolic processes essential for survival, although this mechanism calls for more investigations.32

All drugs containing artemisinin are metabolized in the body to dihydroartemisinin, a sesquiterpene lactone endoperoxide.44 This endoperoxide is responsible for the death of parasites by cleaving them and producing free radicals. To activate artemisinin, the reduced form of Fe2+ iron catalyzes reductive scission of the endoperoxide bond.44 The main source of this iron is probably imported host hemoglobin, which, when proteolyzed, produces extremely reactive heme species. Although most of this heme is trapped in hemozoin crystals, a small amount would be left vacant and accessible for artemisinin activation. Other iron sources, including the low steady-state labile iron pool found in parasites, may be used for artemisinin activation.45

Lastly, there is evidence that the parasite’s biosynthetic heme may also activate ART in early rings.46 This reliance on free Fe2+ for activation illustrates why ARTs are proactive against blood-stage parasites but ineffective against liver stages or mature gametocytes.47

Mechanisms of artemisinin resistance

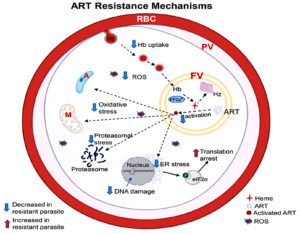

One vital component of antimalarial therapies is artemisinin, which is particularly effective against Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest malaria parasite species.48 However, artemisinin resistance has emerged, primarily in Southeast Asia and, more recently, in Africa,49 emphasizing the demand for a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms. This complex resistance involves mutations in key genes, cellular stress response alterations, and hemoglobin uptake modification as shown in Figure 3.50

In clinical terms, artemisinin resistance is the inability of patients receiving artemisinin derivatives or artemisinin combination therapy to rapidly eliminate malaria parasites from their peripheral blood.43 Slow parasite clearance and decreased early ring-stage parasite susceptibility are characteristics of ART resistance.51 The relationship between ART resistance and polymorphisms in the Plasmodium falciparum Kelch 13 propeller protein has been shown by numerous studies, and parasites with different SNPs in the gene encoding it (PfK13) exhibit different parasite clearance rate phenotypes.52 The PfK13 is now widely recognized as a reliable indicator of artemisinin resistance. However, about twenty more recorded polymorphisms need to be phenotypically described for their effects on parasite sensitivity to ARTs.53 Currently, parasites with PfK13 mutations, such as R561H, F446I, N458Y, M476I, Y493H, R539T, C580Y, I543T, and P553L, are linked to reduced in vitro drug sensitivity and delayed clearance in clinical trials.54

The most well-known genetic basis for artemisinin resistance is associated with alterations in the Pfk13 protein.55 These variations have been linked with delayed parasite clearance after treatment, indicating decreased vulnerability to Artemisinin. A summary of PfATPase6 gene mutations reported in previous studies, along with their prevalence, associated IC50 increases, and genotyping methods, is presented in Table 2.

Table (2):

Summary of PfATPase6 gene mutations recorded from existing selected literature

| Mutation | Country | Genotyping/Sequencing method | Prevalence % | Associated IC50 Increase | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E431K | North-Eastern Tanzania | PCR-RFLP for PfATPase6 gene mutations | 16 | Yes (Artemether) | 56 |

| Nigeria | PCR + Sequencing | 17 | NA | 11 | |

| Gabon, Ghana, and Kenya | PCR, Sanger sequencing | 41 | NA | 57 | |

| Republic of Congo | Nested PCR | 1.6 | NA | 58 | |

| L263E | North-Eastern Tanzania | PCR-RFLP for PfATPase6 gene mutations | 5.8 | Yes | 56 |

| A623E, | Gabon, Ghana, and Kenya | PCR, Sanger sequencing | 3.1 | NA | 57 |

| S769N | North-Eastern Tanzania | PCR-RFLP for PfATPase6 gene mutations | 3.9 | Yes | 56 |

| S769M | Southwest Nigeria | PCR, Sanger sequencing | 3.6 | 59 | |

| M699V | Southwest Nigeria | PCR, Sanger sequencing | 9.6 | 59 | |

| S679S | Southwest Nigeria | PCR, Sanger sequencing | 8.4 | 59 | |

| R37K | Somalia (Afgol and Balad) | PCR-RFLP, Sanger sequencing | 3.5 | NA | 60 |

| G639D | Somalia (Afgol and Balad) | PCR-RFLP, Sanger sequencing | 4.7 | NA | 60 |

| I898I | Somalia (Afgol and Balad) | PCR-RFLP, Sanger sequencing | 33.7 | NA | 60 |

NA = Not Applicable

Research has proven that a specialized point mutation in the K13 propeller domain results in a notable reduction in drug potency, enabling the survival of parasites regardless of exposure to ART.56 The rise of these mutations has been noticed as a selective response to the pressure brought about by Artemisinin-based therapies, resulting in drug-driven selection across several Plasmodium falciparum populations.

The mechanism of action of Artemisinin is directly associated with the breakdown of hemoglobin within the parasite’s food vacuole.57 The process starts with endocytosis of hemoglobin from the host red blood cells (RBC) through cytostomes.58 This uptake is essential because the breakdown of hemoglobin generates heme, which is hazardous to the parasite but also necessary to activate Artemisinin.59 Decreased breakdown and hemoglobin uptake have been linked to changes in molecules involved in hemoglobin transport (AP-2 µ, Rab GTPases, and Coronin). By implication, this results in lesser production of heme and reduced activation of Artemisinin, ultimately decreasing oxidative stress within the parasite.60

Recent studies have emphasized the function of Transfer Ribonucleic Acid (tRNA) alteration in conferring resistance to Artemisinin.61 Adjustments in tRNA molecules enable Plasmodium falciparum to swiftly fit the expression of its protein profile under drug-induced conditions. This acclimatization allows the survival of resistance strains regardless of reduced levels of heme and artemisinin activation.61 The ability to modify tRNA insinuates a complicated level of regulation that improves the parasite’s resilience against therapeutic strategies.62

Artemisinin employs its impact partially via the production of reactive oxygen species after heme activation as shown in Figure 2.42 There is proof that reactive oxygen species are modified either via alterations in metabolic pathways that combat oxidative stress response or by a reduction in the availability of heme.63 This modification enables resistant strains to tolerate the cellular injury induced by Artemisinin. Figure 3 presents mechanisms of ART resistance in Plasmodium falciparum.

Impact of Pfatpase6 mutations on the effectiveness of artemisinin-based therapies

The PfATPase6 gene is a significant focus point in Plasmodium falciparum regarding malaria treatment outcomes, especially in relation to artemisinin-based combination therapies. Studies have pointed out specific mutations in this gene that correspond with decreased susceptibility to treatments, making close investigation of their effects on malaria management necessary.

Research has linked decreased susceptibility to artemisinin-based treatments to several single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).64 Studies have reported that decreased sensitivity to artemisinin is associated with specific mutations. Notably, the E431K mutation occurs in approximately 17% of samples from affected regions.

Furthermore, the S769N mutation is linked to an increased Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) value for artemether, implying a correlation with artemisinin resistance. However, the prevalence depends on the region.65,66 Mutation such as A623E is usually studied alongside E431K, which may contribute to decreased drug efficacy with other SNPs.65 Other forms like L263E and R37K have been reported but infrequently. These mutations reveal the genetic diversity and adaptive abilities of Plasmodium falciparum in response to drug pressure from artemisinin-based combination therapies.12,65

A study in Nigeria specifically investigated the molecular profile of the PfATPase6 gene among Plasmodium falciparum isolates and ascertained a minimal prevalence of already established SNPs associated with resistance, indicating that other factors may be part of treatment failures.11 Conversely, broader studies have investigated numerous genes (pfmdr1, pfcrt, and others, including PfATPase6).66 These investigations often show complex interactions between various genetic factors affecting antimalarial drug resistance, revealing that while Pfatpaes6 is important, it is among a broader network of genes that collectively impact treatment outcomes.

A recent finding emphasizes the significance of continuous molecular surveillance, aiding an improved comprehension of the dynamics of these mutations and their implications in malaria treatment options.67 Constant surveillance would be imperative as new mutations may emerge due to selective pressure from the broad use of ACTs.

Research utilizing field isolates and eukaryotic models has suggested that changes in in vitro sensitivity to Artemisinin or its derivatives are caused by SNPs in the PfATPase6 gene.68 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated in many studies that PfATPase6 has many SNPs, four of which (L263E, E431K, A623E, and S769N) have been linked to a significant rise in artemether IC50.69

However, previous research with P. falciparum revealed that the main target of these medications may be a sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA)-type protein encoded by the gene pfatp6, and mutations in this gene could alter P. falciparum’s susceptibility to artemisinin.70 The idea that PfATPase6 is a target for artemisinin emphasizes the necessity of a continuous fight against malaria to mitigate the emergence of resistance to these therapies.

After heterologous expression of PfATPase6, inhibitor profiles for antimalarial activity in vitro showed a positive association.70 Parasites transfected with the PfATPase6 mutant L263E-PfATPase6 exhibited reduced sensitivity to artemisinin and dihydroartemisinin in both ex vivo and in vivo tests and greater variability in sensitivity assays.70

Comparative synthesis of studies reporting PfATPase6 mutations

Although SNPs like S769N and E431K have been observed in regions such as Tanzania, Brazil, and Nigeria, research on their direct impact on phenotypic resistance remains uncertain.71 Nguetse et al.57 recorded a high frequency of the E431K mutation (118 cases in 287 samples), which could suggest a possible hotspot for the mutation, probably because of high antimalarial pressure among the studied population. The E431K may be adaptive in response to artemisinin-based combination therapies, improving parasite survival because the PfATPase6 gene is implicated in calcium transport and ATPase functions. Suradji et al.56 and Adedire et al.11 observed a moderate occurrence of the E431K mutation (16.2% and 17%), respectively. These differences may be due to variations in the partner drug combinations employed in ACTs, sampling times, and parasite genetic backgrounds, which may suggest that, regardless of the E431K mutation, the selection pressure in these regions may not be high compared to Nguetse et al.57 It will be important to investigate if these two studies were carried out in regions with low usage of ACT, contrary to Nguetse et al.57

Standardized methods, such as ex vivo IC50 measurements and ring-stage survival assays, must be employed in future studies to investigate the functional importance of mutations in the PfATPase6 gene. Koukouikila-Koussounda et al.58 observed a very low frequency of 2 cases in 120 samples (1.7%). This obvious variation from other studies with the same mutation indicates that the mutation is not widespread yet in the population, or that artemisinin drug pressure is notably very low in this region. Moreover, variations in the genetic backgrounds of parasites in this region could impact the presence of the mutation.

The E431K in the PfATPase6 gene is suspected to impact artemisinin resistance through numerous mechanisms. It could impair the function of ATPase, possibly impacting the transport of calcium ions within the parasite.72,73 Furthermore, it may be associated with compensatory mutations that allow parasites to survive regardless of exposure to ACTs.70 While this mutation could be linked to decreased sensitivity to artemisinin, more research is required to define its specific role in resistance.74 This corresponds with the findings of Chilongola et al.71 who proposed that the PfATPase6 E431K variant has been linked with enhanced artemether IC50 when found in alongside mutation A623E in P. falciparum isolates. In their study, this mutation (E431K) was the second most prevalent (16.4%) due to its occurrence at every site sampled and was present in three different haplotypes.

Tola et al.75 examined 83 samples and observed three distinct mutations (M699V, S679S, and S769M). Among the three mutations, M699V had a relatively high prevalence (9.6%), although its specific impact is still uncertain. S769M was found among 3 samples out of the 83 samples analysed (3.6%). This mutation has been pointed out in recent studies as a candidate marker implicated in artemisinin resistance because of its effect on the role of ATPase. A synonymous mutation such as S679S (8.4%) usually has no functional role but might be associated with nearby resistance-conferring variations.

Out of the 86 samples examined by Jalei et al.,60 four distinct mutations were identified (R37K, I898I, S769N, and G639), having mutation frequencies of 3/86, 29/86, 0/86, and 4/86, respectively. The R37K and G639D have not been broadly studied concerning resistance, which makes their significance uncertain. The synonymous mutation (I898I) does not incur any changes in the amino acid sequence, but its high frequency suggests that it could be a polymorphism that occurs frequently among Plasmodium falciparum populations. Remarkably, the S769N was absent among the 86 samples analysed, even though a similar mutation(S769M) was identified in a study by Mwaiswelo et al.76 This implies that while S769M may be significant in resistance, S769N is not implicated. In a similar study by Hassan et al.,77 all the 1000 (100%) isolates carried the wild-type allele, which shows that there are no S769N mutations for the PfATPase6 gene in that region at present. Since there was no artemisinin-resistant gene detected in the study, it was concluded that the drug remains effective against malaria in that area.

Demographic factors for PfATPase6 mutations

Recent research has highlighted the notable influence of age and gender on malaria rate and resistance to antimalarials, especially mutations in the PfATPase6 gene.72 The prevalence of malaria in many sub-Saharan regions is high in children below the age of five (5) years due to their underdeveloped immune systems.73 This demographic trend implies that young people are more vulnerable to severe malaria, which may impact the selection pressure for drug resistant strains of malaria. Gender disparities are significant in the epidemiology of malaria.74

Research has revealed that males could be at higher risk of malaria infection compared to females because of their frequent outdoor activities and the risk of their jobs.65 Additionally, biological factors associated with gender could influence immunological responses, which may affect the emergence of resistance to antimalarial drugs.78 Studies have ascertained that the prevalence of certain mutations in the PfATPase6 could differ among genders, although there is insufficient data to support this notion.75

Prevalence of PfATPase6 mutations in Nigeria

Plasmodium falciparum, which causes malaria, possesses a gene known as PfATPase6. The gene (PfATPase6) is associated with resistance to antimalarial drugs, specifically artemisinin-based combination therapies.32 Efforts to control malaria are hindered by the presence of mutations in this gene, especially in endemic regions or rural areas with limited access to healthcare.

Recent research has highlighted the prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum in the Southwestern part of Nigeria. Wicht et al.32 observed several antimalarial drug resistance markers alongside mutations in PfATPase6 and other key resistance genes, such as pfcrt and pfmdr1.32 Non-synonymous mutations in the PfATPase6 were observed in this research from samples of symptomatic malaria patients, indicating a possible correlation to reduced drug efficacy. In another research on the molecular detection of drug-resistant polymorphisms, 3.6% of the tested cases exhibited ACT-resistant-related single-nucleotide polymorphisms (S769) in PfATPase6, highlighting the significance of continuous surveillance.76

Molecular detection methods for PfATPase6 mutations

The PfATPase6 gene in Plasmodium falciparum is an essential marker in evaluating artemisinin resistance.76 Numerous detection methods have been the target of recent research to identify mutations in this gene, which is necessary for understanding the mechanisms underlying antimalarial drug resistance. Several molecular methods have been utilized to identify mutations in the PfATPase6 gene. The Polymerase chain reaction is the primary method of detecting mutations, followed by Sanger sequencing.77

In a study conducted in Brazil, the scientists used PCR to amplify specific regions of the genome to detect polymorphisms at codons 37, 630, and 898, with a significant prevalence of mutation, including R37K at 16% and A630S at 32% observed in the isolates.78 The Mutation Surveyor enhanced the analysis of these sequences, emphasizing the effectiveness of automated techniques in identifying genetic mutations.

The PCR-RFLP (Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism) is another broad technique to detect SNPs linked with artemisinin resistance.79 A study in Tanzania employed PCR-RFLP to evaluate mutations such as L263E and E431K and discovered the prevalence rate of local isolates.80 This approach allows rapid analysis of multiple samples and is essential for epidemiological research.

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is also an effective technique in molecularly characterizing the PfATPase6 mutations.65 This method quantifies gene copy number and can be employed in Allelic discrimination, making it possible for researchers to distinguish between wild and mutant alleles efficiently. A study in Nigeria utilized RT-qPCR to evaluate the prevalence of mutations linked with resistance to antimalarial drugs, revealing its usefulness in high-throughput settings.76

Genotyping techniques are essential in understanding the prevalence of the PfATPase6 gene mutations in various geographic regions and their interaction with artemisinin resistance.72 One such technique that has gained attention is High-Resolution Melting analysis (HRM), which can differentiate between closely related genotypes without broad post-PCR processing. This method was efficiently utilized in research that evaluated Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Iran, and mutations were linked to treatment outcomes.78

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques are revolutionizing research, making it possible to conduct a detailed analysis of genetic diversity in the PfATPase6 gene.68 The NGS can provide an understanding of several mutations simultaneously and their possible interactions, providing more holistic insights into the impact of mutations on resistance mechanisms.81 Studies utilizing NGS have evaluated new mutations that may not be feasible with conventional methods, highlighting the significance of adopting advanced genomic technologies in malaria research.

To evaluate how specific PfATPase6 mutations affect drug binding or calcium transport, subsequent studies must go beyond conventional genotypic cataloguing and introduce functional genomics methods, like Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats CRISPR associated protein 9(CRISPR-Cas9)-based gene editing alongside heterologous expression platforms. Treatment outcome models could be enhanced by incorporating PfATPase6 mutation data into real-time resistance monitoring frameworks like those for PfK13

Limitations

This review is limited by its reliance on previously published articles, which differ in study design, study population, and geographic distribution. Data from several African regions remains insufficient, making it hard to make continent-wide inferences. Furthermore, the biological role of several PfATPase6 mutations has not been completely verified in a clinical or experimental context, and differences in the use of partner drugs may further complicate interpretation. These limitations emphasize the demand for more detailed, region-specific studies and functional genomic investigations to spell out the contribution of PfATPase6 mutations to artemisinin resistance. Bridging these gaps will enhance global initiatives to sustain the potency of ACTs and educate future malaria therapeutic approaches.

Prospect for future research and treatment strategies

The obvious evidence of the impact of PfATPase6 mutations highlights the necessity for ongoing surveillance to monitor dynamics in resistance patterns. Evaluating genetic mutations within Plasmodium falciparum is vital for comprehending resistance mechanisms and ensuring efficient treatment protocols.33 Although certain mutations have been linked to altered vulnerability to artemisinin treatments, the total effect on treatment efficacy diverges notably across different areas.12 Looking forward, certain areas need more exploration. Functional genomic research is essential to understand the biological importance of mutations in the PfATPase6 gene and their interplay with other determinants of resistance.

Broadening research in marginalized regions of Africa will help bridge knowledge gaps and improve the completeness of surveillance data. Furthermore, utilizing NGS and other advanced molecular methods will enhance the sensitivity for detecting minor forms that can act as early signals of emerging resistance.

Maintaining the potency of artemisinin and its partner medications will therefore need a cohesive approach that combines clinical surveillance, molecular epidemiology, and improved health systems. Further research should focus on clarifying these interplays and delving more deeply into other molecular markers that could be implicated in resistance, thereby facilitating efforts to mitigate malaria efficiently.

The emergence of artemisinin resistance in P. falciparum presents a notable challenge in efforts to mitigate malaria worldwide. This article examined the genetic basis of resistance, with a major focus on mutations in the PfATPase6 gene. Findings propose that certain mutations (A623E, L263E, and E431K) could impair drug efficacy, highlighting the necessity for continuous molecular surveillance of these genetic mutations; however, there are variations in the frequency of occurrence and clinical impact across regions. The study points out that although mutations in the PfATPase6 gene have been linked to altered treatment potency, their prevalence and effect differ across diverse regions, including Nigeria’s populace. Additionally, demographic factors affecting the frequency of the PfATPase6 gene mutations were evaluated, providing valuable information on how local populations may respond to artemisinin-based combination therapies. The molecular methods of detection explored provided vital tools to identify these genetic mutations in medical settings, allowing early interventions; hence, the impact of demographics and the parasite’s genetic basis further affects treatment outcomes. Sustained genetic monitoring alongside advanced detection techniques will be vital to maintain the efficiency of ACTs.

Genetic-based knowledge of ART resistance will be critical in developing efficient protocols, enhancing global health policies aimed at malaria eradication. Continuous research on PfATPase6 gene mutations and other resistant genes is imperative to guarantee the effectiveness of treatment regimens against emerging strains of Plasmodium falciparum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors appreciate the Covenant University Centre for Research Innovation and Discovery (CUCRID) for covering the publication costs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

This study was funded by Covenant Applied Informatics and Communication Africa Center of Excellence (CApIC-ACE), Scholarship, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Not applicable.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Olasehinde GI, Diji-Geske RI, Fadina I, et al. Epidemiology of Plasmodium falciparum infection and drug resistance markers in Ota Area, Southwestern Nigeria. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:1941-1949.

Crossref - Oranusi SU, Mameh EO, Oyegbade SA, Balogun DO, Aririguzoh VGO. Inhibitors of Protein Targets of Plasmodium falciparum. j pure Appl Microbiol. 2024;18(4):251-2162.

Crossref - Alghamdi JM, Al-Qahtani AA, Alhamlan FS, Al-Qahtani AA. Recent advances in the treatment of malaria. Pharm. 2024;16(11):1416.

Crossref - Septembre-Malaterre A, Rakoto ML, Marodon C, et al. Artemisia annua, a Traditional Plant Brought to Light. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(14):4986.

Crossref - Narula AK, Azad CS, Naiwal LM. New dimensions in the field of antimalarial research against malaria resurgence. Eur J Med Chem Rep. 2019;181:111353.

Crossref - Kuesap J, Suphakhonchuwong N, Kalawong L, Khumchum N. Molecular Markers for Sulfadoxine/Pyrimethamine and Chloroquine Resistance in Plasmodium falciparum in Thailand. Korean J Parasitol. 2022;60(2):109-116.

Crossref - Maiga FO, Wele M, Toure SM, et al. Artemisinin-based combination therapy for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Mali: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Malar J. 2021;20(1):356.

Crossref - World Health Organization. World malaria report 2018. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria -programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2018 Accessed: 26 December 2024.

- World Health Organization. World malaria report 2022. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2022 Accessed: 30 October 2024.

- Pongwattanakewin O, Phyu T, Suesattayapirom S, Jensen LT, Jensen AN. Possible Role of the Ca2+/Mn2+ P-Type ATPase Pmr1p on Artemisinin Toxicity through an Induction of Intracellular Oxidative Stress. Molecules. 2019;24(7):1233.

Crossref - Adedire ND, Iwegbulam NC, Funwei NR, et al. Molecular profile of Pfatpase-6 gene from Plasmodium falciparum isolates in Nigeria. Int J Life Sci Res. 2023;4(1):029-035.

Crossref - Obasi DO, Azorji JN, Onyenwe NE, Duru OO. Analysis of Knowledge Management Practice Studies among the Plasmodium falciparum Positive Patients Attending Outpatient Departments in Awka, South Anambra State. Int J Trop Dis Health. 2019;35(3):1-13.

Crossref - NaB J, Efferth T. Development of artemisinin resistance in malaria therapy. Pharmacol Res. 2019;146:104275.

Crossref - Kumar A, Singh P, Verma GK, et al. Pondering Plasmodium: revealing the parasites driving human malaria and their core biology in context of antimalarial medications. Gupta Y, Kumar PS, Kushwah RBS. eds. Breaking the Cycle of Malaria – Molecular Innovations, Diagnostics, and Integrated Control Strategies. IntechOpen eBooks.2024.

Crossref - Nwinyi OC, Balogun DO, Isibor PO, et al. Environmental Impact Assessment for Sustainable Development in Malaria-Endemic Regions: Addressing the Threat of Drug-Resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Africa. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2024;1428(1):012013.

Crossref - Arora G, Chuang YM, Sinnis P, Dimopoulos G, Fikrig E. Malaria: influence of Anopheles mosquito saliva on Plasmodium infection. Trends Mol. 2023;44(4):256-265.

Crossref - Sinka ME, Pironon S, Massey NC, et al. A new malaria vector in Africa: Predicting the expansion range of Anopheles stephensi and identifying the urban populations at risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(40):24900-24908.

Crossref - Singh M, Suryanshu N, Kanika N, Singh G, Dubey A, Chaitanya RK. Plasmodium’s journey through the Anopheles mosquito: A comprehensive review. Biochimie. 2020;181:176-190.

Crossref - Maier AG, Matuschewski K, Zhang M, Rug M. Plasmodium falciparum. Trends Parasitol. 2018;35(6):481-482.

Crossref - Burns AL, Dans MG, Balbin JM, et al. Targeting malaria parasite invasion of red blood cells as an antimalarial strategy. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2019;43(3):223-238.

Crossref - Matz JM, Beck JR, Blackman MJ. The parasitophorous vacuole of the blood-stage malaria parasite. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18(7):379-391.

Crossref - Jensen AR, Adams Y, Hviid L. Cerebral Plasmodium falciparum malaria: The role of PfEMP1 in its pathogenesis and immunity, and PfEMP1 based vaccines to prevent it. Immunol Rev. 2019;293(1):230-252.

Crossref - Reyes-Lopez M, Aguirre-Armenta B, Pina-Vazquez C, De La Garza M, Serrano-Luna J. Hemoglobin uptake and utilization by human protozoan parasites: a review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1150054.

Crossref - Zambare KK, Thalkari AB, Tour NS. A review on Pathophysiology of malaria: An overview of etiology, life cycle of malarial parasite, clinical signs, diagnosis and complications. Asian Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2019;9(3):226-230.

Crossref - Wiser MF. Knobs, adhesion, and severe falciparum malaria. Trop Med Infect. 2023;8(7):353.

Crossref - Zhong A, Zhang H, Li J. Insight into molecular diagnosis for antimalarial drug resistance of Plasmodium falciparum parasites: A review. Acta Tropica. 2023;241:106870.

Crossref - Dash M, Sachdeva S, Bansal A, Sinha A. Gametogenesis in Plasmodium: delving deeper to connect the dots. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:877907.

Crossref - Lamy A. Lipid Flippases from Plasmodium Parasites: From Heterologous Production towards Functional Characterization [doctoral dissertation]. Paris, France: Université Paris-Saclay; 2018. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02088128

- Habtamu K, Petros B, Yan G. Plasmodium vivax: the potential obstacles it presents to malaria elimination and eradication. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2022;8(1):27.

Crossref - Escalante AA, Cepeda AS, Pacheco MA. Why Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum are so different? A tale of two clades and their species diversities. Malar J. 2022;21(1):139.

Crossref - Arya A, Foko LPK, Chaudhry S, Sharma A, Singh V. Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) and drug resistance molecular markers: A systematic review of clinical studies from two malaria endemic regions – India and sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Parasitol Drugs. 2020;15:43-56.

Crossref - Wicht KJ, Mok S, Fidock DA. Molecular Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in Plasmodium falciparum Malaria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2020;74(1):431-454.

Crossref - La Fuente IMD, Benito MJS, Ousley J, et al. Screening for K13-Propeller Mutations Associated with Artemisinin Resistance in Plasmodium falciparum in Yambio County (Western Equatoria State, South Sudan). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023;109(5):1072-1076.

Crossref - Musyoka KB, Kiiru JN, Aluvaala E, et al. Prevalence of mutations in Plasmodium falciparum genes associated with resistance to different antimalarial drugs in Nyando, Kisumu County in Kenya. Infect Genet Evol. 2019;78:104121.

Crossref - Kim J, Tan YZ, Wicht KJ, et al. Structure and drug resistance of the Plasmodium falciparum transporter PfCRT. Nature. 2019;576(7786):315-320.

Crossref - Ramirez AM, Akindele AA, Gonzalez-Mora V, et al. Mutational profile of pfdhfr, pfdhps, pfmdr1, pfcrt and pfk13 genes of P. falciparum associated with resistance to different antimalarial drugs in Osun state, southwestern Nigeria. Trop Med Health. 2025;53(1):49.

Crossref - Baina MT, Djontu JC, Mbama-Ntabi JD, et al. Polymorphisms in the Pfcrt, Pfmdr1, and Pfk13 genes of Plasmodium falciparum isolates from southern Brazzaville, Republic of Congo. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):27988.

Crossref - Dakorah MP, Aninagyei E, Attoh J, Adzakpah G, Tukwarlba I, Acheampong DO. Profiling antimalarial drug-resistant haplotypes in Pfcrt, Pfmdr1, Pfdhps and Pfdhfr genes in Plasmodium falciparum causing malaria in the Central Region of Ghana: a multicentre cross-sectional study. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2025;12:20499361251319665.

Crossref - Balta VA, Stiffler D, Sayeed A, et al. Clinically relevant atovaquone-resistant human malaria parasites fail to be transmitted by mosquitoes. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):6415.

Crossref - Wu K, Yao Y, Chen F, et al. Analysis of Plasmodium falciparum Na+/H+ exchanger (pfnhe1) polymorphisms among imported African malaria parasites isolated in Wuhan, Central China. BMC Infect Dis. 2019:19(1):354.

Crossref - Auparakkitanon S, Wilairat P. Ring stage dormancy of Plasmodium falciparum tolerant to artemisinin and its analogues – A genetically regulated “Sleeping Beauty.” Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2023;21:61-64.

Crossref - Dieng CC, Morrison V, Donu D, et al. Distribution of Plasmodium falciparum K13 gene polymorphisms across transmission settings in Ghana. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):801

Crossref - Zheng D, Liu T, Yu S, Liu Z, Wang J, Wang Y. Antimalarial mechanisms and resistance status of artemisinin and its derivatives. Trop Med Infect. 2024;9(9):223.

Crossref - Lu F, He XL, Richard C, Cao J. A brief history of artemisinin: Modes of action and mechanisms of resistance. Chin J Nat Med. 2019;17(5):331-336.

Crossref - Rahman A, Tamseel S, Dutta S, et al. Artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum Kelch13 mutant proteins display reduced heme-binding affinity and decreased artemisinin activation. Commun Biol. 2024;7(1):1499.

Crossref - Liu S, Wei C, Liu T, et al. A heme-activatable probe and its application in the high-throughput screening of Plasmodium falciparum ring-stage inhibitors. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):160.

Crossref - Kannan D, Yadav N, Ahmad S, et al. Pre-clinical study of iron oxide nanoparticles fortified artesunate for efficient targeting of malarial parasite. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:261-277.

Crossref - Tse EG, Korsik M, Todd MH. The past, present, and future of anti-malarial medicines. Malar J. 2019;18(1):93.

Crossref - Balikagala B, Fukuda N, Ikeda M, et al. Evidence of Artemisinin-Resistant malaria in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(13):1163-1171.

Crossref - Rosenthal MR, Ng CL. Plasmodium falciparum Artemisinin Resistance: The Effect of Heme, Protein Damage, and Parasite Cell Stress Response. ACS Infect Dis. 2020;6(7):1599-1614.

Crossref - Siddiqui FA, Liang X, Cui L. Plasmodium falciparum resistance to ACTs: Emergence, mechanisms, and outlook. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2021;16:102-118.

Crossref - Platon L, Menard D. Plasmodium falciparum ring-stage plasticity and drug resistance. Trends Parasitol. 2023;40(2):118-130.

Crossref - Iwuafor A, Ogban G, Elem D, et al. Plasmodium falciparum Kelch 13-propeller gene mutation update in Nigeria – a systematic review. The Nigerian Health Journal. 2023;23(2).

- Agaba BB, Travis J, Smith D, et al. Emerging threat of artemisinin partial resistance markers (pfk13 mutations) in Plasmodium falciparum parasite populations in multiple geographical locations in high transmission regions of Uganda. Malar. J. 2024;23(1):330.

Crossref - Kahunu GM, Thomsen SW, Thomsen LW, et al. Identification of the PfK13 mutations R561H and P441L in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Int J Infect Dis. 2023;139:41-49.

Crossref - Siddiqui FA, Boonhok R, Cabrera M, et al. Role of Plasmodium falciparum Kelch 13 Protein Mutations in P. falciparum Populations from Northeastern Myanmar in Mediating artemisinin Resistance. mBio. 2020;11(1):1134-19.

Crossref - Suradji EW, et al. Polymorphism of pfcrt K76T and pfatpase6 S769N Genes in Malaria Patients at Teluk Bintuni Regency, Papua, Indonesia. Pharmacol Clin Pharm Res. 2016;1(1).

Crossref - Nguetse CN, Adegnika AA, Agbenyega T, et al. Molecular markers of anti-malarial drug resistance in Central, West and East African children with severe malaria. Malar J. 2017;16(1):217.

Crossref - Koukouikila-Koussounda F, Jeyaraj S, Nguetse CN, et al. Molecular surveillance of Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance in the Republic of Congo: four and nine years after introducing artemisinin-based combination therapy. Malaria J. 2017;16(1):1-7.

Crossref - Lechuga GC, Pereira MCS, Bourguignon SC. Heme metabolism as a therapeutic target against protozoan parasites. J Drug Target. 2018;27(7):767-779.

Crossref - Jalei AA, Na-Bangchang K, Muhamad P, Wanna C. Monitoring antimalarial drug-resistance markers in Somalia. Parasites, Hosts and Diseases, 2023;61(1):78.

Crossref - Small-Saunders JL, Sinha A, Bloxham TS, et al. tRNA modification reprogramming contributes to artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Microbiol. 2024;9(6):1483-1498.

Crossref - Tewari SG, Rajaram K, Swift RP, Reifman J, Prigge ST, Wallqvist A. Metabolic Survival Adaptations of Plasmodium falciparum Exposed to Sublethal Doses of Fosmidomycin. J Antimicrob Agents. 2021;65(4):e02392.

Crossref - Vasquez M, Zuniga M, Rodriguez A. Oxidative stress and pathogenesis in malaria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11.

Crossref - Owoloye A, Olufemi M, Idowu ET, Oyebola KM. Prevalence of potential mediators of artemisinin resistance in African isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Malar J. 2021;20(1):451.

Crossref - Sutherland CJ, Henrici RC, Artavanis-Tsakonas K. Artemisinin susceptibility in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum: propellers, adaptor proteins and the need for cellular healing. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2020;45(3): fuaa056.

Crossref - Patel P, Bharti PK, Bansal D, et al. Prevalence of mutations linked to antimalarial resistance in Plasmodium falciparum from Chhattisgarh, Central India: A malaria elimination point of view. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):16690.

Crossref - Chinnappanna NKR, Yennam G, Chaitanya CBHNV, et al. Recent approaches in the drug research and development of novel antimalarial drugs with new targets. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;73(1):1-27.

Crossref - Hjelmqvist D. Effects of DNA damage and vesicular exchange in P. falciparum (Order No. 28423710). Available from ProQuest One Academic. (2572679686). 2019. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/effects-dna-damage-vesicular-exchange-em-p/docview/2572679686/se-2

- Fola AA, Ciubotariu II, Dorman J, et al. National genomic profiling of Plasmodium falciparum antimalarial resistance in Zambian children participating in the 2018 Malaria Indicator Survey. medRxiv. 2024.

Crossref - Goomber S, Mishra N, Anvikar A, Valecha N. Geographic Plasmodium falciparum sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (PfSERCA) genotype diversity in India. Acta Trop. 2019;202:105095.

Crossref - Chilongola J, Ndaro A, Tarimo H, et al. Occurrence of PfATPase6 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Associated with Artemisinin Resistance among Field Isolates of Plasmodium falciparumin North-Eastern Tanzania. Malar Res Treat. 2015;2015(1):1-7.

Crossref - World Health Organization. World malaria report 2024. Geneva: WHO.2024. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2024 Accessed: 13 September 2025.

- Watson OJ, Gao, B, Nguyen TD, et al. Pre-existing partner-drug resistance to artemisinin combination therapies facilitates the emergence and spread of artemisinin resistance: a consensus modelling study. Lancet Microbe. 2022;3(9):e701-e710.

Crossref - Okiring J, Epstein A, Namuganga JF, et al. Gender difference in the incidence of malaria diagnosed at public health facilities in Uganda. Malar J. 2022;21(1):22.

Crossref - Tola M, Ajibola O, Idowu ET, Omidiji O, Awolola ST, Amambua-Ngwa A. Molecular detection of drug-resistant polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Southwest, Nigeria. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):497.

Crossref - Mwaiswelo R, Ngasala B, Jovel I, et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors Associated with Polymerase Chain Reaction-Determined Plasmodium falciparum Positivity on Day 3 after Initiation of Artemether-Lumefantrine Treatment for Uncomplicated Malaria in Bagamoyo District, Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2019;100(5):1179-1186.

Crossref - Hassan AO, Ademujumi OG, Popoola AO. Molecular screening of S769N mutation for PFATPASE in subjects with plasmodiasis in Owo. Int J Med Biomed Res. 2016;5(1):28-34.

- Mamudu CO, Iheagwam FN, Okafor EO, Dokunmu TM, Ogunlana OO. Contriving a novel multi-epitope subunit vaccine from Plasmodium falciparum vaccine candidates against malaria. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2024;14(09):156-168.

Crossref - Cheng W, Wang W, Zhu H, Song X, Wu K, Li J. Detection of Antimalarial Resistance-Associated Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum via a Platform of Allele-Specific PCR Combined with a Gold Nanoparticle-Based Lateral Flow Assay. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(6):e0253522.

Crossref - Qamar F, Ashrafi K, Singh A, Dash PK, Abdin MZ. Artemisinin production strategies for industrial scale: Current progress and future directions. Ind Crop Prod. 2024;218:118937.

Crossref - Murmu LK, Sahu AA, Barik TK. Diagnosing the drug resistance signature in Plasmodium falciparum: a review from contemporary methods to novel approaches. J Parasit Dis. 2021;45(3):869-876.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.