Mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue, Zika, chikungunya, and lymphatic filariasis continue to impose enormous health and economic burdens worldwide. The traditional reliance on chemical insecticides has been undermined by the rapid evolution of resistance, ecological concerns, and declining efficacy. Next-generation biocontrol strategies are framed within the concept of a “genomic arms race” between mosquitoes, pathogens, and microbial agents. Entomopathogenic fungi are eco-friendly bioinsecticides with demonstrated efficacy in laboratory, semi-field, and transgenic applications. Symbiont-based approaches, particularly those involving Wolbachia, have been evaluated for their ability to reduce vector competence and spread through populations. Parallel advances in CRISPR-based gene drive technologies have provided transformative tools for population suppression and modification, although their deployment is limited by ethical, ecological, and regulatory concerns. An integrated vector management (IVM) framework combining fungi, gene drives, and symbiont-based tools is proposed as the most promising approach for sustainable mosquito management. This multipronged strategy has the potential to reduce disease transmission, delay resistance development, and minimize ecological disruption, paving the way for resilient, eco-friendly solutions against vector-borne diseases.

Mosquito Management, Entomopathogenic Fungi, Wolbachia, Gene Drive, Vector-borne Diseases, Genomic Arms Race, Integrated Vector Management

Mosquitoes are among the most important vectors of human and animal diseases, responsible for transmitting malaria, dengue, Zika virus, chikungunya, and lymphatic filariasis. Together, these diseases account for hundreds of millions of cases annually and continue to impose heavy public health and economic burdens worldwide.1 Malaria alone accounted for an estimated 249 million cases and over 600,000 deaths in 2022, whereas dengue is now considered the most rapidly spreading arboviral disease, with half of the world’s population at risk.2 Emerging arboviruses, such as Zika and chikungunya, have further highlighted the vulnerabilities of global vector surveillance and control programs.3 Globally, mosquito-borne diseases exert a tremendous economic burden on public health systems and national economies. The cumulative cost attributed to Aedes mosquitoes and their associated arboviruses from 1975-2020 is estimated at US$ 94.7 billion, averaging approximately US$ 3.29 billion per year, with peaks reaching ~US$ 20.9 billion in 2013.4,5 At a national scale, Brazil’s dengue vector control programs have consumed nearly US$ 1 billion each year, underscoring the immense fiscal pressure of mosquito management in endemic regions.6

Historically, vector control has relied heavily on chemical insecticides, which have been applied through indoor residual spraying, space spraying, and insecticide-treated nets.7 Although these interventions contributed significantly to malaria reduction in the early 2000s, their long-term effectiveness is now undermined by widespread resistance to insecticides. Resistance to pyrethroids, organophosphates, and carbamates has been documented in major mosquito genera, including Anopheles and Aedes.8,9 This resistance not only reduces the efficacy of control tools but also threatens to reverse the progress in malaria and arbovirus management.10 Moreover, chemical-based interventions raise environmental and public health concerns, including non-target impacts, bioaccumulation, and community hesitancy toward large-scale spraying.11 The ability to develop resistance to both synthetic and biological insecticides, compounded by ecological pressures, poses a major challenge to arboviral management in tropical regions.12 Global climate change is facilitating the expansion of mosquito habitats and prolonging transmission seasons, thereby increasing the potential for the transmission of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya in regions that are not traditionally endemic.13

Notably, resistance has extended beyond synthetic insecticides and now encompasses biological larvicides and botanical formulations. Field populations of Aedes aegypti L. (Diptera; Culicidae) and Culex quinquefasciatus Say (Diptera; Culicidae) have shown reduced susceptibility to the microbial larvicide Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis Barjac (Bti) (Bacillales; Bacillaceae) in several regions, linked to repeated exposure and selection pressure.14 Similarly, tolerance to Lysinibacillus sphaericus Meyer and Neide (Bacillales; Bacillaceae) formulations has emerged in African and Asian mosquito populations, driven by midgut receptor mutations that reduce toxin binding efficiency.15 Furthermore, cases of reduced sensitivity to botanical insecticides, such as neem (Azadirachta indica) and pyrethrum-based formulations, have been observed due to adaptive metabolic detoxification mechanisms in Aedes albopictus (Skuse) and Anopheles stephensi Liston (Diptera; Culicidae).16,17

The limitations of insecticide-based approaches underscore the urgent need for sustainable, evolution-resilient, and environmentally friendly alternatives to vector management. Innovative approaches, such as entomopathogenic fungi (EPF), gene drive technologies, and symbiont-based interventions (e.g., Wolbachia), represent promising tools to complement and eventually replace the reliance on chemicals.18,19 This review explores these next-generation strategies through the lens of the “genomic arms race”, the co-evolutionary struggle between mosquitoes, pathogens, and microbial control agents, and evaluates their roles in shaping sustainable mosquito-borne disease management.

The genomic arms race: Mosquito-pathogen-microbe interactions

The transmission of mosquito-borne diseases is shaped by a continuous co-evolutionary struggle between mosquito vectors, pathogens, and the microbial agents influencing these dynamics. This interaction, often described as a “genomic arms race”, involves reciprocal adaptations that determine the vector competence and disease outcomes.

Mosquitoes possess a complex innate immune system that defends against invading pathogens through several key pathways, including Toll, immune deficiency (IMD), Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT), and RNA interference (RNAi).20 These pathways orchestrate antimicrobial peptide expression, melanization, and cellular immunity, which restrict pathogens such as Plasmodium and arboviruses.21 In response, pathogens have evolved immune evasion strategies, including the suppression of signaling cascades and the exploitation of mosquito midgut microbiota.22 For instance, Plasmodium ookinetes secrete proteins to evade melanization, whereas the dengue virus modulates RNAi pathways to enhance replication.23

Microbial symbionts and entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) play important roles in shaping evolutionary dynamics. Endosymbionts, such as Wolbachia, modify host immunity and reduce vector competence by enhancing reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and interfering with pathogen replication.18,19 Similarly, gut microbiota have been shown to modulate immune priming and affect susceptibility to infection.24 Entomopathogenic fungi (EPF), such as Metarhizium anisopliae (Metchnikoff) Sorokin (Hypocreales: Clavicipitaceae) and Beauveria bassiana (Balsamo) Vuillemin (Hypocreales: Cordycipitaceae), are known to activate the Toll and IMD pathways. However, they frequently circumvent host immune defenses by secreting immune-suppressive metabolites.25,26

From the perspective of the pathogen, adaptation to mosquito immunity and microbial competitors is crucial for successful transmission. Arboviruses display high genomic plasticity, which enhances their fitness across multiple mosquito species,27 Similarly, malaria parasites continually evolve antigenic diversity to evade immune recognition in both vertebrate and invertebrate hosts.28 This ongoing interplay forms a triangular evolutionary battlefield among mosquitoes, pathogens, and their microbial associates.

Comprehending these arms race dynamics is essential, as they contribute to the development of innovative vector management strategies. By exploiting microbial symbionts and EPF, researchers can develop natural antagonists of mosquito vectors and their pathogens. Moreover, genetic technologies such as CRISPR-based gene drives can directly modify mosquito immunity or reproduction, potentially reshaping the evolutionary balance among vectors, pathogens, and microbes.29,30

Entomopathogenic fungi as Eco-friendly Mosquito biocontrol agents

Entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) have emerged as promising and environmentally sustainable alternatives to chemical insecticides for mosquito management. Unlike conventional chemical agents, fungi such as M. anisopliae and B. bassiana infect mosquitoes through direct contact with their cuticles. The fungal conidia adhere, germinate, and penetrate the hemocoel, where they proliferate by depleting nutrients and releasing insecticidal metabolites, ultimately leading to the death of the host31 This unique infection route reduces the likelihood of resistance development compared with chemical insecticides.32,33

Recent advances in fungal biotechnology have further enhanced their biocontrol potential. Transgenic Metarhizium strains engineered to express anti-Plasmodium effector molecules or insect-selective toxins exhibit rapid killing and transmission-blocking efficacy in malaria-endemic regions.34 Wang et al. highlighted that engineered fungal systems, when integrated into vector management frameworks, can complement genetic and symbiont-based tools by providing strong short-term suppression.30

The efficacy of EPF is often influenced by environmental conditions, with high humidity favouring spore viability, whereas UV radiation reduces persistence in open environments.35 Recent advancements in formulation science, encompassing oil-based emulsions, nanoparticle carriers, and electrostatic spraying technologies, have effectively addressed these limitations.36 Recent studies have highlighted the potential of diverse Metarhizium and Beauveria species as sustainable mosquito biocontrol agents (Table). For instance, a transgenic Metarhizium pingshaense Chen and Guo (Hypocreales; Clavicipitaceae) expressing anti-Plasmodium peptides demonstrated near-complete blocking of disease transmission in semi-field trials,37 whereas indigenous isolates such as M. anisopliae TK-6 from India achieved up to 96% larval mortality in Ae. aegypti and C. quinquefasciatus.38 B. bassiana nano formulations induced over 90% mortality in Anopheles and Aedes species.39,40 These findings reaffirm the adaptability of EPFs and their potential for integration into environmentally sustainable mosquito control programs.

Table:

The use of EPF strains and their efficacy against mosquito vectors

EPF strain |

Country |

Formulation |

Mechanism |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

M. pingshaense (Transgenic strain) |

Burkina Faso |

Engineered fungus expressing anti-Plasmodium peptide |

Effector proteins blocking parasite development |

Rapid mosquito mortality and complete Plasmodium transmission blocking in semi-field trials.37 |

M. anisopliae TK-6 |

India |

Solid-state fermentation (rice bran substrate), conidial suspensions (10v -10x conidia/mL) |

Cuticle penetration, spore adhesion, secondary metabolites |

96% larval mortality in Ae. aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus at 10x conidia/mL within 96 hrs.38 |

B. bassiana (myco- synthesized AgNPs) |

India |

Myco-synthesis of silver nanoparticles (36-60 nm), tested against larval instars |

Silver nanoparticle toxicity + fungal metabolites |

LC50 = 0.79 ppm; LC90 = 1.09 ppm; 100% mortality in 1st-2nd instars; up to 86.6% in late instars at 1 ppm.94 |

B. bassiana strain MHK |

USA |

Laboratory bioassay using conidial suspensions (1 × 10w – 1 × 10x conidia/mL) applied to A. gambiae and Ae. albopictus larvae |

Cuticular penetration; hyphal proliferation in hemocoel; production of Beauvericin and Bassianolide toxins |

85%-95% larval mortality at 1 × 10x conidia/mL; delayed pupation and adult emergence.39 |

B. bassiana strain BBPTG4 |

Mexico |

Spore suspension bioassay (1 × 10x conidia/mL) against Ae. aegypti adults |

Cuticle infection; enzymatic degradation via proteases and chitinases; toxin secretion |

LT50 = 7.5 days for BBPTG4; cumulative mortality > 90% after 10 days.40 |

Molecular and immunological responses of mosquitoes to fungal infections

Mosquitoes possess a multilayered immune defense system that is rapidly activated following exposure to EPF such as M. anisopliae and B. bassiana. Initial recognition occurs via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect fungal cell wall components, triggering canonical innate immune pathways, such as the Toll, IMD, and JAK-STAT pathways.41 These cascades lead to the upregulation of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), including defensins, cecropins, and gambicins, which contribute to fungal growth suppression.42 Melanization, mediated by the prophenoloxidase (PPO) cascade, is a critical component of the antifungal immunity of mosquitoes.43 Activation results in the encapsulation of fungal hyphae and the production of cytotoxic intermediates that restrict fungal proliferation.44 Experimental silencing of immune-related genes, such as Relish, STAT-A, and Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO) enzymes, significantly enhances fungal pathogenicity, underscoring the importance of these pathways in defense.45

Interestingly, immune responses against fungi often overlap with antiviral and antiparasitic defenses, suggesting a shared evolutionary origin of mosquito immunity.46 For example, RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown of Dicer-2 and Argonaute-2 increases fungal susceptibility, linking antiviral RNAi to antifungal defense.47 Moreover, fungal infections can dysregulate mosquito physiology by modulating oxidative stress pathways, metabolism, and gut microbiota composition.48 Symbiotic bacteria further complicate this interaction. Wolbachia-infected Ae. aegypti display altered susceptibility to Metarhizium infections, likely due to the symbiont-induced priming of the Toll and IMD pathways.48 This complex crosstalk illustrates how mosquito immunity is continuously shaped by interactions among fungi, symbionts, and pathogens.49 Collectively, molecular and immunological investigations demonstrate that fungal infections in mosquitoes are not passive occurrences; rather, they activate intricate host defense mechanisms.

Symbiont-based strategies: Wolbachia and microbial interference

Wolbachia, a maternally inherited intracellular bacterium, is a promising symbiont-based mosquito control tool. Its ability to manipulate host reproduction through cytoplasmic incompatibility enables rapid spread through mosquito populations.18 Importantly, several strains, including wMel and wAlbB, can block the replication of arboviruses, such as dengue, Zika, and chikungunya, thereby reducing their transmission capacity.50 Field deployments have provided robust epidemiological evidence of this efficacy. The Applying Wolbachia to Eliminate Dengue (AWED) trial conducted in Indonesia reported a 77% reduction in dengue incidence in regions where Wolbachia was released.51 Wolbachia large-scale releases in Brazil resulted in significant reductions in the incidence of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya, despite its heterogeneous prevalence.52 Similarly, city-wide deployments in Colombia have demonstrated stable establishment and reduced arbovirus incidence.53

Recent innovations in symbiont-based mosquito control extend beyond natural Wolbachia infections to paratransgenic strategies that utilize genetically modified (GM) symbiotic bacteria.54 These bacteria, derived from the mosquito midgut microbiome, can be engineered to express antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) or lethal effector molecules that inhibit or destroy pathogens inside the mosquito.55 Once reintroduced, these modified symbionts colonize the gut, establish stable populations, and can be vertically transmitted across generations, providing a self-sustaining and eco-friendly control mechanism. Such approaches have shown potential to disrupt the transmission of arboviruses by blocking pathogen development at the vector stage.56 The overall workflow of this paratransgenic system, from gene selection to transgenerational pathogen interference, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. This schematic illustrates the workflow for developing genetically modified (GM) symbionts for mosquito vector control. Antimicrobial or lethal genes are selected from EPF and inserted into plasmids, which are introduced into symbiotic bacteria isolated from the mosquito midgut. These chimeric symbionts are reintroduced into mosquitoes through feeding, colonize the gut within hours, and inhibit pathogen development. Over successive generations (F1-F3), GM symbionts are vertically transmitted, maintaining pathogen resistance and reducing disease transmission potential

At the molecular level, Wolbachia infection alters mosquito gene expression, particularly in immune and metabolic pathways, which may underlie its antiviral effects.57 The stability of Wolbachia has been confirmed in long-term studies, with wMel strain persisting in Australian populations for over a decade without significant loss of viral blocking capacity.58 Likewise, wAlbB strain has shown thermal stability and robust blocking capacity across diverse mosquito genetic backgrounds.59 These outcomes are consistent with findings from Abbasi, who highlighted that biological interventions such as Wolbachia-based control play a central role within integrated vector management (IVM) frameworks.60,61

Interactions between Wolbachia and Entomopathogenic fungi

The interplay between Wolbachia symbiosis and EPF adds a crucial layer of complexity to mosquito management. While Wolbachia infection generally enhances host immunity and reduces susceptibility to arboviruses.62 it may also confer partial protection against fungal pathogens, thereby limiting the effectiveness of fungal biocontrol.63 Laboratory assays have revealed that Wolbachia-infected Ae. aegypti exhibit reduced mortality when challenged with B. bassiana, suggesting antagonistic interactions mediated by immune priming.64,65 Conversely, studies have indicated that engineered M. pingshaense strains can overcome these defenses by delivering insect-specific toxins, achieving higher virulence even in Wolbachia-carrying populations.24

Recent studies have indicated that these interactions are context-dependent. In some Anopheles and Culex species, Wolbachia coinfection does not reduce fungal infection rates, suggesting potential synergism.29 Moreover, fungal infections may suppress Wolbachia-induced reproductive advantages, influencing cytoplasmic incompatibility dynamics.66 Field studies in Africa and Southeast Asia suggest that combining fungal sprays with Wolbachia releases could enhance vector suppression if strain compatibility and environmental parameters are optimized.29,61 Future research should focus on the effects of genetic background, host immune trade-offs, and temperature stressors that may shift the balance between fungal virulence and Wolbachia-mediated protection.67,68 Collectively, these findings position Wolbachia-fungus interactions as both a challenge and an opportunity in next-generation integrated vector management.

Gene drive technologies: CRISPR-based vector suppression

Gene drive systems exploit biased inheritance to rapidly spread engineered traits through mosquito populations, surpassing classical Mendelian expectations. With the advent of CRISPR-Cas9 editing, highly efficient drives have been constructed in Anopheles mosquitoes, designed for two primary goals: population suppression and modification.69,70 Suppression drives target fertility-associated genes such as double sex, leading to sterile females and population collapse in caged trials.71 Modification drives aim to introduce refractory traits that block Plasmodium or arbovirus development in mosquitoes, thereby reducing the transmission potential.72,73

Recent advancements have augmented the gene drive toolkit by incorporating split-drive systems, temperature-sensitive drives, and localized or self-limiting drives. These innovations enhance biosafety and facilitate controlled propagation within semi-field environments.74 These innovations reflect a shift toward reversible and geographically confined drives, addressing early ecological concerns about uncontrollable spread.75 Multiplexing guide RNAs and targeting conserved genomic regions are strategies that have been proposed to mitigate resistance.76

In addition to molecular barriers, ecological and ethical considerations are central to gene drive deployment. Field releases raise questions regarding irreversible ecological changes, non-target effects, and community acceptance.77 Global policy discussions have emphasized the importance of containment, reversibility, and governance prior to widespread application.78,79

Advances in next-generation CRISPR-based gene drive systems, including self-limiting and Cas12a-based designs, now offer greater precision and control, mitigating some of these earlier concerns.80 Such innovations, supported by recent modeling and semi-field studies, suggest that responsibly deployed drives could substantially reduce malaria transmission in endemic regions.81 Although CRISPR gene drives are not yet ready for large-scale release, they remain a transformative tool for rigorous scientific and ethical evaluation.

Integrating fungi, gene drives, and symbionts in vector control

Sustainable mosquito management requires a shift from single-method to integrated strategies. EPF, gene drives, and symbiont-based methods are complementary tools with unique strengths that can overcome the limitations of insecticide-based management strategies. EPF, such as M. anisopliae and B. bassiana, provide rapid population suppression through direct infection and pathogenicity. Moreover, recent advances have enabled the engineering of fungal strains capable of expressing antiparasitic effectors that target malaria parasites within mosquitoes.82 Gene drive systems, particularly CRISPR-based drives targeting fertility or pathogen transmission, offer long-term suppression or modification; however, they face resistance evolution and regulatory concerns.83,84 Wolbachia spreads through populations by inducing cytoplasmic incompatibility, a reproductive mechanism that prevents uninfected females from producing viable offspring with infected males, thereby favouring the spread of infection.85,86

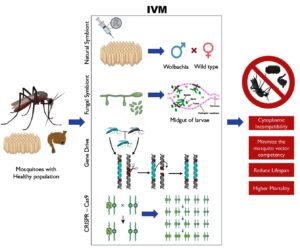

The integration of these methods offers synergistic potential: fungi provide short-term suppression, gene drives enable self-propagating modification, and Wolbachia provides ecological persistence. Studies indicate that combining microbial and genetic tools can reduce the selective pressure on vectors and pathogens, slowing resistance evolution and enhancing sustainability.19,87 Moreover, integrated strategies fit within the World Health Organization (WHO) framework of Integrated Vector Management (IVM), enhancing sustainability and social acceptance (Figure 2).61,88

Figure 2. This schematic illustrates the integrated vector management combining EPF, natural symbionts, and gene drives

Ethical considerations

The use of advanced biocontrol technologies such as Wolbachia, gene drives, and engineered fungi raises important ethical questions. This encompasses ensuring informed consent from the community, clearly communicating potential risks, and equitably sharing the benefits and responsibilities of these interventions.75

Gene drives, in particular, pose challenges because they can spread rapidly through wild populations once they are released. This raises concerns about who has the right to decide when and where such releases should take place, especially in regions that are most affected by mosquito-borne diseases but may have limited regulatory capacity.77,89 Examples from Wolbachia field programs in Australia, Brazil, and Indonesia show that early community engagement and transparent communication are essential for public acceptance.90 The Eliminate Dengue Program (now known as the World Mosquito Program) succeeded largely because it involved local communities in decision-making and used culturally sensitive outreach strategies91 These experiences provide useful models for the ethical planning and implementation of future gene drive projects.

Ecological and environmental risks

Ecological risks associated with these biocontrol methods include potential effects on non-target species, disruption of food webs, and unpredictable evolutionary changes. Engineered fungi may persist in the environment longer than anticipated, potentially affecting native microbial communities. Similarly, Wolbachia infections can introduce ecological uncertainty through horizontal transfer to other insect species or by changing the natural microbiota.19

Gene drives pose the greatest ecological concern because they can spread rapidly and permanently alter mosquito populations across ecosystems and national borders. Although molecular safeguards, such as threshold-dependent drives, split drives, and reversal systems have been developed to limit these risks, their reliability in natural settings remains uncertain.77 Comprehensive environmental monitoring and adaptive management strategies must accompany any field release to detect unintended ecological consequences and resistance evolution.

Regulatory and governance frameworks

The regulatory oversight of biocontrol technologies remains uneven across regions. While Wolbachia field trials have received approval in several countries, gene drive research is still limited to laboratory and semi-field settings because of biosafety concerns.91 Coordinated international regulation is essential, as mosquitoes and their genetic modifications can cross national borders.92

Global bodies such as the WHO, Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety are working to establish guidelines for safe testing and deployment.93 However, there is currently no globally binding framework that clearly defines standards for gene drive research, risk assessment, or responsibility in the case of cross-border impacts.30 Integrating ethical, ecological, and social considerations into these regulations is vital to ensure transparency, accountability, and public trust.

Ultimately, responsible vector control innovation requires balancing the urgent need for sustainable mosquito management with precautionary principles.92,93 Transparent risk communication, participatory decision-making, and iterative policy reviews can help align technological innovations with societal values. Stakeholder engagement, spanning scientists, policymakers, ethicists, and affected communities, will determine whether integrated strategies using fungi, symbionts, and gene drives gain societal acceptance and regulatory approval.

Mosquito-borne diseases continue to pose a major global health challenge, intensified by the spread of insecticide resistance and the adaptive resilience of vector populations. Although historically effective, traditional chemical control methods are no longer sufficient on their own. Emerging biological and genetic tools, such as M. anisopliae and B. bassiana, Wolbachia-based symbiont strategies, and CRISPR-based gene drives offer innovative alternatives for sustainable mosquito suppression and disease prevention.

The future of mosquito control depends on the integration of these complementary methods within an integrated vector management framework. For example, EPF can deliver immediate population suppression, whereas Wolbachia ensures a long-term reduction in vector competence, and gene drives can provide durable genetic modifications for resistance management. Pilot programs could explore sequential or combined field applications, such as releasing Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes in areas pre-treated with fungal biocontrol agents to maximize the short- and long-term impact.

To effectively implement these strategies, researchers should focus on optimizing the compatibility between biological and genetic interventions. Policymakers must establish clear biosafety and regulatory guidelines, and public health authorities should prioritize community engagement and transparent risk communication to foster social acceptance. Rigorous ecological monitoring and adaptive management are essential to ensure environmental safety and long-term effectiveness.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Department of Agricultural Entomology, Centre for Plant Protection Studies, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, for providing the necessary infrastructure and support to carry out this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made substantial, direct, and intellectual contributions to the work and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Not applicable.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Bhatt S, Weiss DJ, Cameron E, et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature. 2015;526(7572):207-211.

Crossref - Thellier M, Gemegah AAJ, Tantaoui I. Global fight against malaria: goals and achievements 1900–2022. J Clin Med. 2024;13(19):5680.

Crossref - Cortes N, Lira A, Prates-Syed W, et al. Integrated control strategies for dengue, Zika, and Chikungunya virus infections. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1281667.

Crossref - Chilakam N, Lakshminarayanan V, Keremutt S, et al. Economic burden of mosquito-borne diseases in low-and middle-income countries: Protocol for a systematic review. JMIR Res Protoc. 2023;12(1):e50985.

Crossref - Roiz D, Pontifes PA, Jourdain F, et al. The rising global economic costs of invasive Aedes mosquitoes and Aedes-borne diseases. Sci Total Environ. 2024;933:173054.

Crossref - Fernandes JN, Moise IK, Maranto GL, Beier JC. Revamping mosquito-borne disease control to tackle future threats. Trends Parasitol. 2018;34(5):359-368.

Crossref - Matthews GA. Integrated vector management: Controlling vectors of malaria and other insect vector-borne diseases. London, UK: FAO/WHO. 2011.

- Yewhalaw D, Kweka EJ. Insecticide resistance in East Africa – history, distribution and drawbacks on malaria vectors and disease control. In: Trdan S, ed. Insecticides Resistance. London, UK: IntechOpen. 2016.

Crossref - Hancock PA, Ochomo E, Messenger LA. Genetic surveillance of insecticide resistance in African Anopheles populations to inform malaria vector control. Trends Parasitol. 2024;40(7):604-618.

Crossref - Riveron JM, Tchouakui M, Mugenzi L, et al. Insecticide resistance in malaria vectors: An update at a global scale. In: Inyang-Etoh PC, ed. Towards Malaria Elimination – A Leap Forward. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2018.

Crossref - Benelli G, Mehlhorn H. Declining malaria, rising of dengue and Zika virus: Insights for mosquito vector control. Parasitol Res. 2016;115(5):1747-1754.

Crossref - Abbasi E. Insecticide resistance and arboviral disease transmission: Emerging challenges and strategies in vector control. J Adv Parasitol. 2025;11:46-59.

Crossref - Abbasi E. Global expansion of Aedes mosquitoes and their role in the transboundary spread of emerging arboviral diseases: A comprehensive review. IJID One Health. 2025;6:100058.

Crossref - Almeida JS, Mohanty AK, Kerkar S, Hoti SL, Kumar A. Current status and future prospects of bacilli-based vector control. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2020;13(12):525-534.

Crossref - Pitton S. A new strategy for mosquito biocontrol based on the improvement of Bacillus thuringiensis effectiveness [doctoral dissertation]. Milan, Italy: University of Milan, Department of Biosciences; 2024. https://hdl.handle.net/2434/1055108

- Senthil-Nathan S. A review of resistance mechanisms of synthetic insecticides and botanicals, phytochemicals, and essential oils as alternative larvicidal agents against mosquitoes. Front Physiol. 2020;10:1591.

Crossref - Pavela R, Kovarikova K, Novak M. Botanical antifeedants: An alternative approach to pest control. Insects. 2025;16(2):136.

Crossref - Flores HA, O’Neill SL. Controlling vector-borne diseases by releasing modified mosquitoes. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(8):508-518.

Crossref - Caragata EP, Dutra HL, Sucupira PH, Ferreira AG, Moreira LA. Wolbachia as translational science: Controlling mosquito-borne pathogens. Trends Parasitol. 2021;37(12):1050-1067.

Crossref - Kumar A, Srivastava P, Sirisena PDNN, et al. Mosquito innate immunity. Insects. 2018;9(3):95.

Crossref - Angleró-Rodríguez YI, MacLeod HJ, Kang S, Carlson JS, Jupatanakul N, Dimopoulos G. Aedes aegypti molecular responses to Zika virus: Modulation of infection by the Toll and JAK/STAT immune pathways and virus host factors. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2050.

Crossref - Dong S, Fu X, Dong Y, Simoes ML, Zhu J, Dimopoulos G. Broad spectrum immunomodulatory effects of Anopheles gambiae microRNAs and their use for transgenic suppression of Plasmodium. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(4):e1008453.

Crossref - Sim S, Jupatanakul N, Dimopoulos G. Mosquito immunity against arboviruses. Viruses. 2014;6(11):4479-4504.

Crossref - Coon KL, Brown MR, Strand MR. Mosquitoes host communities of bacteria that are essential for development but vary greatly between local habitats. Mol Ecol. 2016;25(22):5806-5826.

Crossref - Ramirez JL, Schumacher MK, Ower G, Palmquist DE, Juliano SA. Impacts of fungal entomopathogens on survival and immune responses of Aedes albopictus and Culex pipiens mosquitoes in the context of native Wolbachia infections. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(11):e0009984.

Crossref - Mehmood N, Hassan A, Zhong X, Zhu Y, Ouyang G, Huang Q. Entomopathogenic fungal infection following immune gene silencing decreased behavioral and physiological fitness in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2023;195:105535.

Crossref - Liu Z, Zhou T, Lai Z, et al. Competence of Aedes aegypti, Ae. albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes as Zika virus vectors, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(7):1085.

Crossref - Zhang S, Wang Z, Luo Q, Zhou L, Du X, Ren Y. Effects of microbes on insect host physiology and behavior mediated by the host immune system. Insects. 2025;16(1):82.

Crossref - Bilgo E, Mancini MV, Gnambani JE, et al. Wolbachia confers protection against the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium pingshaense in African Aedes aegypti. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2024;16(4):e13316.

Crossref - Wang GH, Hoffmann A, Champer J. Gene drive and symbiont technologies for control of mosquito-borne diseases. Annu Rev Entomol. 2025;70.

Crossref - Butt TM, Greenfield BP, Greig C, et al. Metarhizium anisopliae pathogenesis of mosquito larvae: A verdict of accidental death. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81686.

Crossref - Perumal V, Kannan S, Pittarate S, Krutmuang P. A review of entomopathogenic fungi as a potential tool for mosquito vector control: A cost effective and environmentally friendly approach. Entomol Res. 2024;54(3):e12717.

Crossref - Rajendran Y, Koushik PV, Sankaran SP, et al. Pathogenicity and ultramicroscopic analysis of green muscardine fungus, Metarhizium anisopliae, infecting the tomato fruit borer, Helicoverpa armigera. Mycologia. 2025;117(4):559-575.

Crossref - Lovett B, Bilgo E, Millogo SA, et al. Transgenic Metarhizium rapidly kills mosquitoes in a malaria-endemic region of Burkina Faso. Science. 2019;364(6443):894-897.

Crossref - Quesada-Moraga E, Gonzalez-Mas N, Yousef-Yousef M, Garrido-Jurado I, Fernandez-Bravo M. Key role of environmental competence in successful use of entomopathogenic fungi in microbial pest control. J Pest Sci. 2024;97(1):1-15.

Crossref - Sarmah K, Anbalagan T, Marimuthu M, et al. Innovative formulation strategies for botanical- and essential oil-based insecticides. J Pest Sci. 2025;98(1):1-30.

Crossref - Bilgo E, Lovett B, Bayili K, et al. Transgenic Metarhizium pingshaense synergistically ameliorates pyrethroid-resistance in wild-caught, malaria-vector mosquitoes. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0203529.

Crossref - Ravindran K, Rajkuberan C, Prabukumar S, Sivaramakrishnan S. Evaluation of pathogenicity of Metarhizium anisopliae TK-6 against developmental stages of Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus. J Pharm Biol Eval. 2015;2(5):188-196.

- Tawidian P, Kang Q, Michel K. The potential of a new Beauveria bassiana isolate for mosquito larval control. J Med Entomol. 2023;60(1):131-147.

Crossref - Zamora-Aviles N, Orozco-Flores AA, Cavazos-Vallejo T, et al. Intra-phenotypic and -genotypic variations of Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill. strains infecting Aedes aegypti L. adults. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(16):8807.

Crossref - Mogensen TH. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(2):240-273.

Crossref - Martinez-Culebras PV, Gandia M, Garrigues S, Marcos JF, Manzanares P. Antifungal peptides and proteins to control toxigenic fungi and mycotoxin biosynthesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(24):13261.

Crossref - Nakhleh J, El Moussawi L, Osta MA. The melanization response in insect immunity. Adv Insect Physiol. 2017;52:83-109.

Crossref - Zdybicka-Barabas A, Staczek S, Kunat-Budzynska M, Cytrynska M. Innate immunity in insects: The lights and shadows of phenoloxidase system activation. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(3):1320.

Crossref - Tafesh Edwards G, Eleftherianos I. The Drosophila melanogaster prophenoloxidase system participates in immunity against Zika virus infection. Eur J Immunol. 2023;53(12):2350632.

Crossref - Waterhouse RM, Kriventseva EV, Meister S, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of immune-related genes and pathways in disease-vector mosquitoes. Science. 2007;316(5832):1738-1743.

Crossref - Liu S, Han Y, Li WX, Ding SW. Infection defects of RNA and DNA viruses induced by antiviral RNA interference. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2023;87(2):e00035-22.

Crossref - Malassigne S, Valiente Moro C, Luis P. Mosquito mycobiota: An overview of non-entomopathogenic fungal interactions. Pathogens. 2020;9(7):564.

Crossref - Zhang W, Chen X, Eleftherianos I, Mohamed A, Bastin A, Keyhani NO. Cross-talk between immunity and behavior: Insights from entomopathogenic fungi and their insect hosts. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2024;48(1):fuae003.

Crossref - Ant TH, Mancini MV, McNamara CJ, Rainey SM, Sinkins SP. Wolbachia-virus interactions and arbovirus control through population replacement in mosquitoes. Pathog Glob Health. 2023;117(3):245-258.

Crossref - Indriani C, Tanamas SK, Khasanah U, et al. Impact of randomised wMel Wolbachia deployments on notified dengue cases and insecticide fogging for dengue control in Yogyakarta City. Glob Health Action. 2023;16(1):2166650.

Crossref - Pinto SB, Riback TIS, Sylvestre G, et al. Effectiveness of Wolbachia-infected mosquito deployments in reducing the incidence of dengue and other Aedes-borne diseases in Niteroi, Brazil: A quasi-experimental study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(7):e0009556.

Crossref - Velez ID, Santacruz E, Kutcher SC, et al. The impact of city-wide deployment of Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes on arboviral disease incidence in Medellin and Bello, Colombia: Study protocol for an interrupted time-series analysis and a test-negative design study. F1000Res. 2020;8:1327.

Crossref - Gao H, Hu W, Cui C, et al. Emerging challenges for mosquito-borne disease control and the promise of symbiont-based transmission-blocking strategies. PLoS Pathog. 2025;21(8):e1013431.

Crossref - Hixson B, Chen R, Buchon N. Innate immunity in Aedes mosquitoes: From pathogen resistance to shaping the microbiota. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2024;379(1901):20230063.

Crossref - Yen PS, Failloux AB. A review: Wolbachia-based population replacement for mosquito control shares common points with genetically modified control approaches. Pathogens. 2020;9(5):404.

Crossref - Wimalasiri-Yapa BMCR, Huang B, Ross PA, et al. Differences in gene expression in field populations of Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes with varying release histories in northern Australia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17(3):e0011222.

Crossref - Ross PA, Robinson KL, Yang Q, et al. A decade of stability for wMel Wolbachia in natural Aedes aegypti populations. PLoS Pathog. 2022;18(2):e1010256.

Crossref - Liang X, Tan CH, Sun Q, et al. Wolbachia wAlbB remains stable in Aedes aegypti over 15 years but exhibits genetic background-dependent variation in virus blocking. PNAS Nexus. 2022;1(4):pgac203.

Crossref - Abbasi E. The impact of climate change on travel-related vector-borne diseases: a case study on dengue virus transmission. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2025;65:102841.

Crossref - Abbasi E. Emerging global health threats from arboviral diseases: a comprehensive review of vector-borne transmission dynamics and integrated control strategies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. SSRN. Published June 16, 2025.

Crossref - Johnson KN. The impact of Wolbachia on virus infection in mosquitoes. Viruses. 2015;7(11):5705-5717.

Crossref - Ramirez A, Brelsfoard CL. A comparison of the structure and diversity of the microbial communities of Culicoides midges. Acta Trop. 2025;266:107622.

Crossref - Paula AR, Silva LEI, Ribeiro A, Butt TM, Silva CP, Samuels RI. Improving the delivery and efficiency of fungus-impregnated cloths for control of adult Aedes aegypti using a synthetic attractive lure. Parasites Vectors. 2018;11(1):285.

Crossref - Katak RdM, Cintra AM, Burini BC, Marinotti O, Souza-Neto JA, Rocha EM. Biotechnological potential of microorganisms for mosquito population control and reduction in vector competence. Insects. 2023;14(9):718.

Crossref - Hochstrasser M. Molecular biology of cytoplasmic incompatibility caused by Wolbachia endosymbionts. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2023;77(1):299-316.

Crossref - Correa CC, Ballard JWO. Wolbachia associations with insects: Winning or losing against a master manipulator. Front Ecol Evol. 2016;3:153.

Crossref - Lindsey ARI, Bhattacharya T, Newton IL, Hardy RW. Conflict in the intracellular lives of endosymbionts and viruses: A mechanistic look at Wolbachia-mediated pathogen-blocking. Viruses. 2018;10(4):141.

Crossref - Adolfi A, Gantz VM, Jasinskiene N, et al. Efficient population modification gene-drive rescue system in the malaria mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5553.

Crossref - Carballar-Lejarazת R, Ogaugwu C, Tushar T, et al. Next-generation gene drive for population modification of the malaria vector mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(37):22805-22814.

Crossref - Li Z, Dong Y, You L, et al. Driving a protective allele of the mosquito FREP1 gene to combat malaria. Nature. 2025;645(8081):746-754.

Crossref - Achee NL, Grieco JP, Vatandoost H, et al. Alternative strategies for mosquito-borne arbovirus control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(1):e0006822.

Crossref - Williams AE, Franz AW, Reid WR, Olson KE. Antiviral effectors and gene drive strategies for mosquito population suppression or replacement to mitigate arbovirus transmission by Aedes aegypti. Insects. 2020;11(1):52.

Crossref - Sanz Juste S, Okamoto EM, Nguyen C, Feng X, Amo VLD. Next-generation CRISPR gene-drive systems using Cas12a nuclease. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):6388.

Crossref - Abbasi E. Innovative approaches to vector control: integrating genomic, biological, and chemical strategies. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2025;87(8):5003-5011.

Crossref - Wang GH, Gamez S, Raban RR, et al. Combating mosquito-borne diseases using genetic control technologies. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4388.

Crossref - Collins JP. Gene drives in our future: Challenges of and opportunities for using a self-sustaining technology in pest and vector management. BMC Proc. 2018;12(8):9.

Crossref - Akbari OS, Bellen HJ, Bier E, et al. Safeguarding gene drive experiments in the laboratory. Science. 2015;349(6251):927-929.

Crossref - Zapletal J, Najmitabrizi N, Erraguntla M, Lawley MA, Myles KM, Adelman ZN. Making gene drive biodegradable. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2021;376(1818):20190804.

Crossref - Ajibola FO, Ogunmoyero TS, Lawal M, et al. Gene editing approaches to combat infectious diseases: therapeutic innovations and diagnostic platforms. World J Biol Pharm Health Sci. 2025;22(2):389-418.

Crossref - Smidler AL, Akbari OS. CRISPR technologies for the control and study of malaria-transmitting anopheline mosquitoes. Parasites Vectors. 2025;18(1):252.

Crossref - Qin Y, Liu X, Peng G, Xia Y, Cao Y. Recent advancements in pathogenic mechanisms, applications and strategies for entomopathogenic fungi in mosquito biocontrol. J Fungi. 2023;9(7):746.

Crossref - Wedell N, Price TAR, Lindholm AK. Gene drive: progress and prospects. Proc R Soc B. 2019;286(1917):20192709.

Crossref - Zhao Y, Li L, Wei L, Wang Y, Han Z. Advancements and future prospects of CRISPR-Cas-based population replacement strategies in insect pest management. Insects. 2024;15(9):653.

Crossref - Kaur R, Meier CJ, McGraw EA, Hillyer JF, Bordenstein SR. The mechanism of cytoplasmic incompatibility is conserved in Wolbachia-infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes deployed for arbovirus control. PLoS Biol. 2024;22(3):e3002573.

Crossref - Minwuyelet A, Petronio GP, Yewhalaw D, et al. Symbiotic Wolbachia in mosquitoes and its role in reducing the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases: Updates and prospects. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1267832.

Crossref - Wang GH, Du J, Chu CY, Madhav M, Hughes GL, Champer J. Symbionts and gene drive: Two strategies to combat vector-borne disease. Trends Genet. 2022;38(7):708-723.

Crossref - Marcos-Marcos J, de Labry-Lima AO, Toro-Cardenas S, et al. Impact, economic evaluation, and sustainability of integrated vector management in urban settings to prevent vector-borne diseases: A scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):83.

Crossref - Moreno RD, Valera L, Borgono C, Castilla JC, Riveros JL. Gene drives, mosquitoes, and ecosystems: an interdisciplinary approach to emerging ethical concerns. Front Environ Sci. 2024;11:1254219.

Crossref - Ogunlade ST, Adekunle AI, McBryde ES. Mitigating dengue transmission in Africa: the need for Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes’ rollout. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1506072.

Crossref - Anders KL, Indriani C, Ahmad RA, et al. The AWED trial (Applying Wolbachia to Eliminate Dengue) to assess the efficacy of Wolbachia-infected mosquito deployments to reduce dengue incidence in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):302.

Crossref - Kuzma J. Gene drives: Environmental impacts, sustainability, and governance. In: Florin M-V, ed. Ensuring the Environmental Sustainability of Emerging Technologies. Lausanne: EPFL International Risk Governance Center; 2023.

Crossref - James SL, Dass B, Quemada H. Regulatory and policy considerations for the implementation of gene drive-modified mosquitoes to prevent malaria transmission. Transgenic Res. 2023;32(1-2):17-32.

Crossref - Banu AN, Balasubramanian C. Myco-synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Beauveria bassiana against dengue vector, Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol Res. 2014;113(8):2869-2877.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.