ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

An outbreak of acute gastrointestinal illness occurred among personnel in an army camp in West Sikkim, India, between 27 June and 4 July 2023. The investigation aimed to determine the extent of the outbreak, identify the causative organism and source of infection, and implement effective control measures. A case was defined as any individual residing or working in the camp who, during the outbreak period, experienced ≥3 loose stools within 24 h, accompanied by abdominal pain or vomiting. Clinical samples including stool and rectal swabs, along with food and water samples, were collected and tested using conventional bacteriological culture methods and by multiplex PCR. Data were organized in Microsoft Excel to prepare a line list and epidemic curve was plotted by date and time of onset acute gastroenteritis (AGE) along with calculation of age specific attack rates. A total of 30 army personnel living in an army camp suffered from AGE with an attack rate of 13.5%. The mean age of case patients was 35.7 years (standard deviation ±6.85). Culture results revealed the presence of multiple bacteria including Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. The presence of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) was confirmed by multiplex PCR in rectal swab samples. The findings suggest that the most probable cause of the outbreak was contamination of the in-camp water supply network due to inadequate maintenance and possible sewage infiltration. Timely clinical intervention and public health response effectively curtailed the outbreak and prevented further transmission.

Acute Gastroenteritis (AGE), Outbreak, Multiplex PCR, Enteric Pathogens, Shiga Toxin Producing E. coli (STEC)

Food safety is an important discipline for human health and animal husbandry. In the developing countries, food and hydric transmission event are major public health problem, causing deaths among children under five years old. Despite the fact that prompt investigation is necessary to control, contain the infection and reduce death among affected, most of the outbreaks remain inappropriately investigated, mainly delayed due to the involvement of multifaceted factors and processing systems. When significant number of people are affected by presence of similar clinical signs and symptoms at the same time period with history of ingestion of common food/meals, are basically defined as foodborne outbreaks.1 Preparation of large quantity of foods under unhygienic conditions or poor quality of materials for a substantial number of people like hostels, nursing homes, hospitals, prisons etc., can be generally considered as a hotspot for food poisoning outbreaks.2,3 In a military establishment, infectious diseases in the form of outbreaks have a serious impediment and can affect sizeable number of individuals,4 like disrupt the operational function of the system.5 It is estimated that around 2-2.5 million people suffer from diarrhea every year.6 Indian continent is reporting several outbreaks associated with diarrheal infections favored by number of factors. In many rural areas, there is a shortage of clean water supply, resulting in waterborne infections. Several reports revealed a correlation of diarrheal diseases with consumption of contaminated drinking water.7-12 The mixing of sewage and animal waste in the water sources like rivers, canals, streams, the surrounding areas of water distribution point is very common, especially in rural areas or villages, which is a known factor for the transmission of enteric pathogens from these sources.13 In the rural areas, water is generally collected from underground or spring water. These are used for various purposes like cooking, bathing, farming, etc. However, unlike the public water supplied by the government that undergoes various purification procedures and checked for quality before final supply to various households, ground water or spring water are not purified except boiling or by other purification methods at certain households.

Globally, recent surveillance among deployed U.S. military personnel has also highlighted diarrheagenic E. coli, including STEC, as a major cause of operational gastroenteritis underscoring the continuing relevance of STEC in military settings.14 A recent investigation from Tripura reported a waterborne outbreak caused by Enteroaggregative E. coli and Shigella flexneri/sonnei linked to fecal contamination of a public pipeline.15 Unlike that community based outbreak, the present study describes a STEC associated event in a confined military camp, highlighting the first such report from Sikkim under the ICMR-FoodNet surveillance program. Sikkim is a north-eastern state of the Indian subcontinent, which shares three international borders. It is an advantageously located hill state accounting for 0.2% of the total area of India. It is one of the smallest states in India, both in terms of population (~6.32 lakhs) and area (7096 sq kms). In this work, we report a suspected hydric transmission event in an army camp based in West Sikkim that occurred between 27th June and 4th July 2023. Based on the epidemiological observations and microbiological findings, we report this outbreak by time, person and place, identification of potential exposure and submit evidence-based suggestions.

Outbreak setting

The Food Borne Pathogen (FBP) investigation team from the Department of Microbiology, Sikkim Manipal Institute of Medical Sciences (SMIMS), Gangtok, Sikkim, India, is a part of Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) FoodNet task force surveillance project, conducted the investigation. The team was initially notified about the suspected foodborne outbreak on 4th July 2023 in an army camp in West Sikkim by the Integrated Disease Surveillance Program (IDSP) team (West Sikkim). The investigation team consists of scientist, epidemiologist, lab technician and medical social worker, reached the site for inspection on 5th July 2023. It was observed that more than 30 army soldiers (jawans) had attended army camp dispensary with symptoms of acute gastroenteritis (AGE) since the early morning of 27th June 2023 around 3 am. An epidemiological surveillance was initiated to determine the source of infection, identify the aetiological agent, assess the extent of outbreak and suggest control measures. Further, active case finding was conducted by reviewing the medical register of the cases in the camp and comprehensive cases search in the staff quarters of the camp.

Case definition

A case was defined as any individual who resided or worked in the camp and developed diarrhea/passed loose stools (>3 times) within 24 hrs, abdominal pain, or vomiting with onset between June 27 and July 4, 2023. A descriptive study was carried out to investigate the outbreak. For this, standardized structured questionnaire was made to collect information about socio-demography, clinical data and food history of the patients, laboratory report and outcome. Informed written consent was taken from the cases before the initiation of the questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the ICMR-Central Ethics Committee on Human Research (CECHR) (Reference Number: CECHR/BEU/ICMR-CECHR/75/2020 as well as Ethics Committee (Reference Number: SMIMS/IEC/2019-116, approved on 7th Sept., 2019) of Sikkim Manipal University (SMU), Gangtok, which is one of the sites for ICMR FoodNet project in which outbreak investigation has also been included. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant before enrolling the cases for data collection and stool/rectal sample collection where applicable.

Laboratory investigations

Following the notification of outbreak, rectal swabs and stool samples were collected from symptomatic cases and transported in Cary Blair medium to the laboratory. These samples were processed in the Department of Microbiology, SMIMS. Suspected rectal swabs, stool samples, food samples, water samples, environmental swabs and swabs from food handlers of the camp mess were also collected and processed. Samples were tested for the common enteric pathogens using conventional bacterial culture and biochemical identification methods following the standard methods.14 The isolated Escherichia coli (E. coli) were further tested for the presence of diarrheagenic E. coli (DEC) (ETEC, EPEC, EIEC, EAEC and STEC) in the multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeted diarrheagenic E. coli virulence genes including stx1 (348 bp) and stx2 (584 bp) for STEC, eae (482 bp) and bfpA (300 bp) for EPEC, lt (218 bp) and stII (129 bp) for ETEC, aap (310 bp) and aggR (629 bp) for EAEC and virF (618 bp) and ipaH (933 bp) for EIEC.16

Environmental investigations

During the survey, mess, storage rooms, dining hall and various water sources were inspected thoroughly for cleanliness and sanitation. The food handlers were examined to identify any apparent illness. The place of convenience and refuse disposal site were also inspected. The camp had 3 mess; 1 for officers, 1 for junior officers (subedars) and 1 for soldiers (jawans). The investigation team collected water samples from various sources within the camp compound (1: Officer barrack water supply with reverse osmosis (RO) filter; 3 medium size water tanks with taps) as well as from the open spring water source, which was identified as main source of water supply to the entire military establishment. It was at least 500 meters away from the camp in an uphill road.

Data collection and analysis

The data obtained were entered and double checked in Microsoft Excel Office (365 version). A line list was prepared in consultation with IDSP officers and an epidemic curve was plotted by date and time of onset of AGE along with the calculation of age specific attack rates (AR).

Descriptive epidemiology

A total of 223 people resided in the army camp in West Sikkim at the time of investigation. Overall, thirty male patients were identified as cases as per the definition. AR of the outbreak was 13.5%. The ages of the patients ranged from 21 to 50 years. The mean age of case patients was 35.68 (standard deviation ±6.85). The patients aged between 21-30 were found to be the most affected 12 (40%), followed by 31-40 years 16 (53%) (Table 1).

Table (1):

Age group distribution and attack rate of diarrhea cases during outbreak

Age group |

No. of cases (30) |

Attack rate (n = 223) |

|---|---|---|

0-10 |

0 |

0 |

11-20 |

0 |

0 |

21-30 |

12 (40%) |

5.38 |

31-40 |

16 (53%) |

7.17 |

41-50 |

2 (6.6%) |

0.89 |

Total |

30 |

13.45 |

Among the identified cases, 19 (63%) were jawans, 10 (33%) were subedars and 1 (3%) was a cook. Most of the affected cases had symptoms like diarrhea 30 (100%), abdominal pain 29 (97%), nausea 28 (93%), vomiting 26 (87%) and fever 22 (73%). No fatality was reported from this outbreak. The average incubation period of infection was 8 hrs and the period ranged from 0 to 26 hrs. The majority of cases exhibited moderate diarrhea 22 (73%), followed by acute diarrhea 6 (20%) and only 2 (7%) suffered with severe diarrhea.

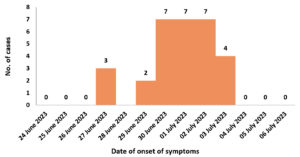

The outbreak curve indicated that the first three cases were reported on 27th June 2023 and additional cases were reported on subsequent days. Peak cases were identified on 30th June, 1st and 2nd July 2023 with seven cases being reported on all three days (Figure 1). The outbreak curve indicated typical picture of a common source of infection.

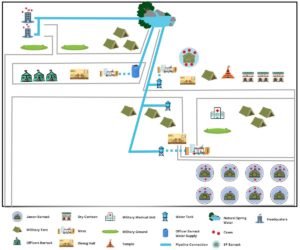

As shown in (Figure 2), the distribution of affected individuals or clustering was mainly found in jawans’ barracks, followed by few other cases in the SP barrack and the camp headquarter. No cases were reported from the officer’s barrack. Among 30 cases, consumption of drinking water by 30 (100%) cases had the strongest association with the illness, 10 (33%) had consumed milk, 6 (20%) rice and veg biryani, 3 (10%) had taken roti and chicken. The only common exposure shared by all cases were food and water from the camp mess. Of the 30 cases, 29 (96.6%) consulted a physician in the camp medical unit, whereas 1 (3.3%) adopted self-medication. The cases were treated with oral fluids 14 (46.6%), antibiotics 29 (96.6%), anti-spasmodic and antacids 16 (53.3%).

Laboratory investigation

Based on the laboratory investigation, of the 18 rectal swabs collected from jawans, staff and subedars with AGE, 17 (94%) samples were culture positive for E. coli and 1 for Klebsiella spp., E. coli was also isolated from two diarrheal stool samples. Out of 13 food samples, E. coli was isolated only from uncooked pulses. E. coli was also isolated from 3 different chopping boards. Out of 5 water samples, E. coli was isolated from 1 tap water of the jawans’ barrack water supply area of the camp. All E. coli isolates were confirmed phenotypically (Table 2).

Table (2):

Identified pathogens and STEC/DEC PCR results of different samples

| Samples | Total number collected | Pathogen identified by culture and biochemical methods | Multiplex PCR confirmation of STEC/DEC Strains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rectal swab | 18 | 17 Escherichia coli | 17 STEC 16 (stx2 gene) |

| 01 Klebsiella spp. | 1 (stx1 + stx2 gene) | ||

| Stool samples | 02 | 02 Escherichia coli | DEC negative |

| Food samples (13) | Basmati rice (02) | 01 Acinetobacter spp. | – |

| 01 Proteus vulgaris | |||

| Lady finger uncooked | Enterobacter spp. | – | |

| Dough | Klebsiella spp. | – | |

| almonds | Klebsiella spp. | – | |

| wheat dough | Klebsiella spp. | – | |

| carrot uncooked | Klebsiella spp. | – | |

| potato cooked | Klebsiella spp. | – | |

| Peanuts | Klebsiella spp. | – | |

| pulses uncooked | Escherichia coli | DEC negative | |

| bottle gourd uncooked | Klebsiella spp. | – | |

| Milk | Klebsiella spp. | – | |

| Chopped onions | Klebsiella spp. | – | |

| Environmental samples | 03 (chopping board swab) | Escherichia coli | DEC negative |

| Water samples (05) | 03- main source but different collection | 02 Aeromonas spp. | – |

| 01 Vibrio spp. | |||

| 01-Tap water | Citrobacter spp. | – | |

| 01-RO water | Escherichia coli | DEC negative |

Multiplex PCR (Eppendorf, Germany) was performed to identify and confirm the presence of diarrhogenic strain of Escherichia coli (DEC) from a total of 24 Escherichia coli identified phenotypically (rectal swab (17) and stool samples (2), food sample (1), environmental samples (3) and water sample (1). The multiplex PCR confirmed the presence of STEC (EHEC) strain of diarrheagenic E. coli, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Confirmation of STEC among DEC isolates by multiplex PCR.

(A) Agarose gel electrophoresis showing amplification of STEC isolates.

Lane 20: DNA molecular size marker (1000 bp ladder)

Lane 19: Reference strain STEC (stx1 amplicon size 348 bp and stx2 amplicon size 584 bp)

Lane 18: Negative control

Lane (1-17): Tested sample

(B): Agarose gel electrophoresis showing amplification of STEC isolates

Lane 40: DNA molecular size marker (1000 bp ladder)

Lane 39: Reference strain STEC (stx1 amplicon size 348 bp and stx2 amplicon size 584 bp)

Lane 38: Negative control

Lane (21-37): Tested sample

Environmental investigation

On inspection of the site by IDSP officers, the following observations were made. The mess and dining area were found to be clean and it was informed that before and after every meal preparation washing and cleaning was done on regular basis. The food handlers also maintained hygiene by using head caps, gloves and aprons. The washing area was also found to be clean. In storage facility, perishable goods were kept in clean wooden racks and covered. The packaged food items were kept in a separate shelf and expiry date logbook was maintained by the store in-charge. The dairy products were refrigerated. The cooked foods were covered and kept on top of a clean bench. The garbage disposal area was located few distance away from the dining area and was properly barricaded with tin sheets. The drainage system was well covered. The sewage pipelines were also checked and found to be satisfactory with no leaks or any broken pipes. In the spring water source, few pipes were found to be connected directly into the mouth of spring water tied with ropes and cloth filters. It was observed that water was supplied directly to the camp with no filtration system in the mess area of SP barrack and jawans barrack. The water tank near the military camp also did not have any filtration set up. It was only in the officer’s barrack, that there was a proper filtration system with RO facility and water was supplied to mess area of officer’s barrack.

One of the key points of United Nations Development Programme’s Sustainable Development Goal 6 is the achievement and delivery of safe drinking water to all humanity.17 This can also be defined as one of civilization’s most efficacious public health interventions that prevails in most of the developed countries. However, probable hazards associated with drinking water systems are the waterborne disease outbreaks in high-risk communities.18

The overall attack rate in our cohort (13.5%) was lower than that reported in a school-camp waterborne outbreak described by Park et al., where 188 of 609 attendees were affected (attack rate 30.9%).19 This difference likely reflects setting and exposure contrasts, the outbreak occurred in an open school-camp population with broad exposure to a contaminated groundwater source and delayed system remediation, whereas our event occurred in a confined military camp where rapid identification and targeted control measures, were instituted early and likely limited further spread. The Tripura investigation of a community waterborne event similarly involved widespread pipeline contamination at the community level and reported an overall attack rate of 0.9%, compared with the 13.5% observed in our outbreak, underscoring how exposure intensity and population structure influence outbreak magnitude.15 Finally, recent surveillance among deployed U.S. military and traveller cohorts has again highlighted diarrheagenic E. coli (including STEC) as an important cause of operational gastroenteritis, reinforcing the global relevance of vigilance and rapid molecular diagnostics in military settings.14 Similarly, a more current outbreak was reported from Utah, USA by Osborn et al., where STEC O157:H7 was associated to untreated municipal irrigation water, our findings reinforce that environmental water systems can serve as unrecognized reservoirs for STEC transmission, especially in institutional or community settings.20

In this study, most of the affected cases had history of consumption of contaminated water and food prepared from same water. Based on the survey of surrounding areas and the main source of water, it was predicted that natural spring water may be the main source, which was located about 500 meters from the camp. Since this spring water was found to be in an open area, it may have been polluted by the animal or human waste.

It was also observed that upstream areas of the spring water were habituated by some locals with agriculture lands and household rearing animals and livestock. STEC has been commonly found in several domestic animals.21 Moreover, during the period of outbreak, study area had been consistently receiving heavy monsoon rains. It is long-established that seasonal rains increase the possibility of diarrheal threat, especially in rural areas.22-25 Thus, based on the findings it is suspected that main natural spring water source might have been contaminated by animal feces/sewage runoff.

In this investigation, the tested rectal swabs were only positive for STEC by the multiplex-PCR indicating that this pathogen might be associated with the disease. STEC are known to persist in food and drinking water due to fecal and secondary contamination.26,27

Recent comparative studies demonstrate that culture-based detection often underestimates diarrheagenic E. coli due to isolation bias and low recovery efficiency, while metagenomic and molecular workflows provide broader detection coverage.28 Similarly, real-time genome-based surveillance has been shown to improve STEC identification and outbreak tracing beyond conventional culture approaches.29

As described in other investigations, the low numbers of organisms below the sensitivity limit of culture conditions, or antibiotic treatment at the time of specimen collection might be the probable reasons for not isolating the STEC in this study from food and water sample.30,31

A significant observation made during this investigation was that in most of the area where many AGE cases were reported, the army personnel consumed water directly from the taps connected to water tanks without any preventive measures like filtration, chlorination or boiling of water practiced. Unlike, in officer’s barrack, where RO water filter was found to be functional. It can be assumed that it may have limited the outbreak in officer’s barracks area, hence, there were no cases reported. A general misconception among the public is that spring water or underground water is generally considered as clean or pure, therefore, untreated water from these sources are consumed directly, placing them at risk of contracting waterborne diseases.

The higher officer in-charge and IDSP Officer, West Sikkim were informed about the results of this study for rapid undertaking of public health measures. As follow-up actions in response to the outbreak described, sensitization on process of water purification process like boiling before consumption, chlorination process at specific areas, cleaning of the spring water at regular basis and maintenance of hygiene at personal level was recommended by the FBP team. Installation of RO water purification system at each mess was also initiated. They were also informed to cover and disinfect natural spring water source which possibly could get mixed up with heavy rain water runoffs. Hydric transmission event linked with polluted source water remain a community health distress around the world and there is a need to monitor the policy of safe water consumption continuously. Outbreaks that occur in certain sensitive areas like army camps, group facilities etc., need to be monitored on a regular basis with systematic surveillance and management of drinking water quality in order to prevent and control hydric transmission event. Following the recommendation, immediate action was adopted by the authorities to stop the spread of the disease and the cases were under control.

In conclusion, our findings support the chances of waterborne transmission of a contaminated natural spring water source. This investigation presented inadequate maintenance of the water distribution system and potential animal sewage/fecal pollution of water were the most plausible causes of outbreak. The rapid initiation of descriptive epidemiological studies in this study helped not only to identify the most likely source of infection, but also undertakes course of specific interventions. It is crucial to have operational control measures with regular trainings, periodic spot investigations and survey to address any infringement of food handling techniques, water management and hygiene practices.

Limitations

Stool sample collection was restricted, as several affected personnel had received antibiotics and were deployed for election duty. This likely reduced culture recovery and molecular confirmation of STEC, since antibiotic exposure can lower isolation efficiency to below 50%. In addition, E. coli serotyping was not performed, limiting further strain characterization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Jawans for their mutual co-operation and patience. The authors are also thankful to the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and Sikkim Manipal Institute of Medical Sciences for their support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

MD and TR performed supervision, project administration, protocol set up and funding acquisition. SD performed spot map generation. EJB and LFL performed epidemiological investigation. KGD, RK, GC, AKM and TR performed laboratory findings. KGD and RK wrote the manuscript. KGD, RK, MD and TR reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, under grant number No. 5/8-I(3)/2019-2020ECD-II(Part-D).

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the ICMR-Central Ethics Committee on Human Research (CECHR) and Ethics Committee of Sikkim Manipal University (SMU), Gangtok, with reference numbers CECHR/BEU/ICMR-CECHR/75/2020 and SMIMS/IEC/2019-116, respectively.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrolling in the study.

- Park K. Food poisoning. In: Park’s Text Book of Preventive and Social Medicine. 17th ed. Jabalpur: M/s Banarsidas Bhanot; 2002:181-184.

- Mandokhot UV, Garg SR, Chandiramani NK. Epidemiological investigation of a food poisoning outbreak. Indian J Public Health. 1987;31(2):113-9.

- Custović A, Ibrahimagić O. Prevention of food poisioning in hospitals. Medicinski arhiv. 2005;59(5):303-5.

- Smallman-Raynor MR, Cliff AD. Impact of infectious diseases on war. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2004;18(2):341 368.

Crossref - Sharp TW, Thornton SA, Wallace MR, et al. Diarrheal diseases among military personnel during Operation Restore Hope, Somalia, 1992-1993. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52(2):188-193.

Crossref - Javed A, Kabeer A. Enhancing waterborne diseases in Pakistan & their possible control. Am Acad Sci Res J Eng Technol Sci. 2018;49(1):248-256.

- Bhunia R, Ramakrishnan R, Hutin Y, Gupte MD. Cholera outbreak secondary to contaminated pipe water in an urban area, West Bengal, India, 2006. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2006;28(2):62-64. Accessed March 1, 2009.

Crossref - Sarkar R, Prabhakar AT, Manickam S, et al. Epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of acute diarrheal disease using geographic information systems. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(6):587- 593.

Crossref - Saha T, Murhekar M, Hutin YJ, Ramamurthy T. An urban, water borne outbreak of diarrhoea and shigellosis in a district town in eastern India. Natl Med J India. 2009;22(5):237-239.

- Fredrick T, Ponnaiah M, Murhekar MV, et al. Cholera outbreak linked with lack of safe water supply following a tropical cyclone in Pondicherry, India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;33(1):31-38.

- Goswami S, Jha A, Sivan SP, Dambhare D, Gupta SS. Outbreak investigation of cholera outbreak in a slum area of urban Wardha, India: an interventional epidemiological study. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2019;8(3):1112-1116.

Crossref - Gwenzi W, Sanganyado E. Recurrent cholera outbreaks in Sub Saharan Africa: moving beyond epidemiology to understand the environmental reservoirs and drivers. Challenges. 2019;10(1):1.

Crossref - Wallender EK, Ailes EC, Yoder JS, Roberts VA, Brunkard JM. Contributing factors to disease outbreaks associated with untreated groundwater. Groundw. 2014;52(6):886-897.

Crossref - Anderson MS, Mahugu EW, Ashbaugh HR, et al. Etiology and epidemiology of travelers’ diarrhea among U.S. military and adult travelers, 2018–2023. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30(14):14:19-25.

Crossref - Majumdar T, Guha H, Tripura A, et al. Outbreak of waterborne acute diarrheal disease in a South District village of Tripura: A public health emergency in the Northeast region of India. Heliyon. 2024;10(11):e31903.

Crossref - Karunasagar I, Ramamurthy T, Das M, Devi U, Baruah P, Panda S. Standard operating procedures ICMR foodborne pathogen survey and research network, North East India. Zenodo. 2022.

Crossref - UNDP. Sustainable-development-goals https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals/clean-water-and-sanitation. Accessed September 10, 2024.

- Hrudey SE, Hrudey EJ. Ensuring safe drinking water: learning from frontline experience with contamination. Denver (CO): American Water Works Association; 2014.

- Park J, Kim JS, Kim S, Shin E, Oh KH, et al. A waterborne outbreak of multiple diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli infections associated with drinking water at a school camp. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2018; 66:45-50.

- Osborn B, Hatfield J, Lanier W, et al. Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 illness outbreak associated with untreated, pressurized, municipal irrigation water Utah, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73(18):412-416.

Crossref - Espinosa L, Gray A, Duffy G, Fanning S, McMahon BJ. A scoping review on the prevalence of shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli in wild animal species. Zoonoses Public Health. 2018;65(8):911-920.

Crossref - Kouadio IK, Aljunid S, Kamigaki T, Hammad K, Oshitani H. Infectious diseases following natural disasters: prevention and control measures. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012;10(1):95-104.

Crossref - Shultz JM, Russell J, Espinel Z. Epidemiology of tropical cyclones: the dynamics of disaster, disease, and development. Epidemiol Rev. 2005;27(1):21-35.

Crossref - Watson JT, Gayer M, Connolly MA. Epidemics after natural disasters. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(1):1-5.

Crossref - Gallay A, De Valk H, Cournot M, et al. A large multi pathogen waterborne community outbreak linked to fecal contamination of a groundwater system, France, 2000. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12(6):561-570.

Crossref - Burke LP, Chique C, Fitzhenry K, et al. Characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli presence, serogroups and risk factors from private groundwater sources in western Ireland. Sci. Total Environ. 2023;25;866:161302.

Crossref - Persad AK, LeJeune JT. Animal reservoirs of Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr. 2014;2(4):EHEC-0027.

Crossref - Royer C, Patin NV, Jesser KJ, et al. Comparison of metagenomic and traditional methods for diagnosis of E. coli enteric infections. mBio; 2024;15(4):e03422-23.

Crossref - Joensen KG, Scheutz F, Lund O, et al. Real-time whole-genome sequencing for routine typing, surveillance, and outbreak detection of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(5):1501-1510.

Crossref - Gerritzen A, Wittke JW, Wolff D. Rapid and sensitive detection of Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli directly from stool samples by real time PCR in comparison to culture, enzyme immunoassay and Vero cell cytotoxicity assay. Clin Lab. 2011;57(11-12):993 998.

- Lefterova MI, Slater KA, Budvytiene I, Dadone PA, Banaei N. A sensitive multiplex, real time PCR assay for prospective detection of Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli from stool samples reveals similar incidences but variable severities of non O157 and O157 infections in northern California. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(9):3000-3005.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.