Soil protists, a diverse group of unicellular eukaryotic microorganisms, play a crucial role in soil ecosystems by regulating microbial populations, enhancing nutrient cycling, and contributing to soil fertility. As microbial predators, they facilitate organic matter decomposition, improve carbon sequestration, and interact with plant roots to promote growth, and their predatory activity suppresses soil-borne plant pathogens, thereby fostering disease-resistant agroecosystems. Beyond their ecological functions, protists serve as bio-indicators of soil health, responding to environmental changes, land use practices, and fertilization regimes. Recent advances in molecular techniques have expanded our understanding of protist diversity and function. However, research on soil protists remains limited, and their potential applications in sustainable agriculture are underexplored. This review examines the diversity, functional roles, and agricultural benefits of soil protists, focusing on their contributions to nutrient availability, plant-microbe interactions, and disease suppression. The recent methodological advancements, research challenges, and future perspectives for integrating protists into soil management strategies is also highlighted in this review. Unlocking the potential of soil protists could provide innovative solutions for improving soil fertility, enhancing crop productivity, and mitigating environmental stressors, ultimately promoting more resilient and eco-friendly agricultural systems.

Soil Protists, Disease Suppression, Nutrient Cycling, Plant-microbe Interactions, Soil Fertility, Sustainable Agriculture

Soil is a biologically diverse environment that supports various microorganisms essential for maintaining its productivity and health. Among these, protists, the unicellular eukaryotes, are crucial yet often ignored in the soil microbiome.1 They play essential roles in microbial population regulation, significantly influencing plant growth and soil health.2 Protists serve as primary consumers and predators within soil food webs, regulating microbial populations through predation on bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms.3 This microbial grazing releases sequestered nutrients, promoting soil productivity and plant nutrient availability. The concept of microbial loop and its extension, the auxiliary microbial loop, highlights how protists indirectly enhance plant growth by stimulating beneficial rhizosphere bacteria.4 Also, protists contribute to the improvement in soil structure and health by influencing microbial enzyme production and decomposition of organic matter.

Unlike bacteria and fungi, protists are highly sensitive to environmental disturbances such as fertilization regimes, land use changes, and climate fluctuations. Their responsiveness makes them valuable bio-indicators of soil health, helping to assess the impact of agricultural practices.5 Recent studies have shown that protistan communities influence the bacterial and fungal interactions to promote plant resilience and suppress soil-borne pathogens.6 Advancements in molecular techniques, such as environmental DNA sequencing and high-throughput analysis, have significantly improved the ability to understand soil protists, revealing their immense diversity and functional importance.7

Animal-like protists, are dominant in soil and play a crucial role in mineral cycling, organic matter decomposition, and microbial population control.8 These protozoa are classified into four groups based on their movement and life cycle characteristics. Sarcodines, such as Amoeba, move using pseudopodia, which are temporary cytoplasmic projections that aid in locomotion and capturing food. Ciliates, including Paramecium, utilize hair-like structures called cilia for movement and feeding. Flagellates, like Giardia, rely on whip-like flagella for propulsion through their environment. Sporozoans, viz., Plasmodium, are typically non-motile in their mature form and are often parasitic. In soil ecosystems, flagellates and amoeboids are the most abundant protist groups, actively feeding on bacteria and regulating microbial communities.9 Their predatory activity contributes to soil health and fertility by influencing the nutrient cycling and microbial dynamics.10

Diversity and functional roles

Soil protists are diverse eukaryotic microorganisms that play crucial roles in terrestrial ecosystems. They are the key drivers of nutrient cycling, particularly through their predation on bacteria and fungi, which release nutrients essential for plant growth.1 Beyond nutrient cycling, protists also contribute to soil fertility by influencing the diversity of microbial communities and promoting organic matter decomposition.10 Their diversity encompasses various functional groups, including bacterivores, fungivores, and mixotrophs, each contributing uniquely to soil ecological processes. Additionally, protists exhibit remarkable adaptability to different environmental conditions, thriving in diverse soil habitats ranging from agricultural fields to forest ecosystems. Their interactions with other soil organisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and even plant roots, further highlight their importance in maintaining soil health and resilience.11

Diversity

Soil protists exhibit the highest β-diversity among terrestrial, freshwater, and marine environments, with over 4,955 unique protist sequence variants (ZOTUs) identified across different soil types. Soil environments harbor the highest taxonomic richness, containing approximately 16,000 OTUs of heterogeneous protists. This is exceeding the diversity observed in aquatic ecosystems, which host 11,000-12,500 OTUs.12 Soil physicochemical properties, such as pH, also influence the protist composition, shaping their diversity and distribution.13 Studies on switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) indicate that bulk soil supports significantly higher protist diversity than rhizosphere soil, with a marked decline in rhizosphere protist diversity during reproductive and maximal growth stages.8 Clay loam soils show greater temporal variability in protist diversity than sandy loam soils. However, the bulk soil display higher beta-diversity fluctuations than rhizosphere samples.14 Specific taxa such as Peronosporales, Sandonidae, and Colpoda dominate the soil environments, with Peronosporales increasing in rhizosphere soil during later plant growth.8 Photosynthetic protists dominate bulk soil communities, including Chlorophyta and Chrysophyceae, contributing to primary productivity and organic matter decomposition.15 Rhizosphere protists form complex co-occurrence networks, particularly during peak plant growth. The key hub taxa viz., Cercomonas and Paracercomonas played a vital role in soil microbial dynamics.16 These findings emphasize the importance of protists in soil ecosystems and highlight the need for further research on their functional roles in microbial dynamics.

Functional role

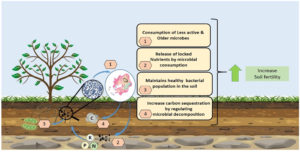

Soil protists, microscopic single-celled eukaryotes, are vital components of ecosystems, performing multiple functional roles. They significantly contribute to nutrient availability by consuming bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms, releasing essential nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus into the soil.1 Their interaction within the soil microbiome helps in maintaining a balanced ecosystem by regulating microbial populations and preventing the overgrowth of certain bacterial or fungal species.17 Figure 1 illustrates the role of protists in agricultural ecosystem.

Carbon cycling

Soil protists play a crucial role in carbon cycling by regulating microbial decomposition, influencing carbon storage, and contributing to organic carbon formation. Photosynthetic protists, such as soil algae and some flagellates, fix atmospheric carbon through photosynthesis, particularly in upper soil layers, enhancing soil organic matter content and promoting microbial activity.18 Heterotrophic protists, including ciliates and amoebae, function as predators that control bacterial populations and influence nutrient dynamics, while parasitic protists contribute to nutrient turnover through the host decomposition. Their predation on bacteria and fungi enhances microbial turnover, accelerating organic matter breakdown and CO2 release. Studies have shown that protists activity increased the litter decomposition by 35% at low temperatures, highlighting their stronger role in carbon cycling in cooler regions where soil carbon storage is higher.19 Additionally, protists increased the microbial enzyme production, which also enhanced the decomposition and nutrient transformation. The soil microbiome, including protists, has been identified as a key component in global carbon cycling, sequestering 80% of the terrestrial carbon stocks and significantly mitigating the climate change.2 Understanding their functional role in soil carbon dynamics aids in developing soil management strategies that enhanced the carbon sequestration and promote sustainable agriculture.

Soil fertility

Soil protists play a vital but often overlooked role in soil fertility management. These microscopic organisms are abundant in soil and serve as primary consumers of bacteria, fungi, algae, and nematodes, making them crucial players in the soil ecosystem.20 Their importance stems from their ability to enhance plant performance through multiple mechanisms. The increased nutrient availability through microbial loop, stimulating beneficial bacteria that promote plant growth, and helps in controlling the harmful microorganisms.21 Several studies have highlighted key differences in how organic and chemical fertilizers influence protist communities. Organic fertilizers promoted beneficial protist populations, while chemical fertilizers tend to favor plant-pathogenic protists. Addition of beneficial microbes like Bacillus or Trichoderma when applied with organic manures, modified the protist communities and reduces the harmful protist populations.22 Wang et al.10 demonstrated that protists act as a central hub in soil microbiome networks, connecting various soil microorganisms and contributing to complex soil food webs. Understanding and managing protist communities offers new opportunities for sustainable agriculture by naturally enhancing the soil fertility, reducing plant pathogens, and improving nutrient transformation.

In a controlled greenhouse study, four different chemical fertilizers, organic manures, organic manures enriched with Bacillus (OF+B), and Trichoderma on soil fertility was studied and found that organic manures applied soil had predatory protists like Stramenopiles, Alveolata, Rhizaria, Excavata, and Amoebozoa as compared to chemical fertilizer treatment. Bacillus added with organic manures reduced the plant-pathogenic protists, particularly affecting Rhizaria and Amoebozoa populations. Higher levels of potentially harmful Pythium species, damaging thousands of plant species was observed in chemical fertilizer treated plots.22

Enhanced bacterial movement

Protists play a crucial role in increasing the bacterial movement within rhizosphere, influencing the spatial distribution of beneficial bacteria such as Sinorhizobium meliloti.23 Micciulla et al.24 demonstrated that protists, including Colpoda sp., Cercomonas sp., and Acanthamoeba castellanii, facilitate bacterial transport through ingestion and egestion, surface attachment, and hydrodynamic currents generated during movement. Colpoda sp. creates feeding currents that pull bacteria towards them, transporting bacteria without ingestion, while Cercomonas sp. carries bacteria on its surface, aiding in dispersal, and Acanthamoeba castellanii moves through pseudopodia, redistributing bacteria in thin water films. A study found that S. meliloti reached distal root regions up to 15 cm farther when co-inoculated with protists as compared to bacterial inoculation alone. Colpoda sp. being particularly effective in increasing nodule formation in Medicago truncatula, resulted in enhanced nitrogen fixation.24 This interaction significantly improved the plant growth, as co-inoculation of protists and S. meliloti resulted in greater shoot biomass, comparable to nitrogen-fertilized plants. Protists also contribute to releasing of nutrients stored in microbial biomass and, benefiting plant health.25 These findings highlighted the potential role of protists as bacterial transport vectors in promoting efficient microbial colonization in plant roots, offering promising applications for sustainable agriculture.

Protist contributions to agroecosystems

Nutrient availability

Protists play a critical role in soil diversity and ecosystem functioning, serving as microbial predators, nutrient recyclers, and regulators of microbial populations. These microorganisms enhance nitrogen and phosphorus availability, by consuming bacteria and fungi, releasing essential nutrients into the soil. Clarholm26 demonstrated that protists increased the plant nitrogen uptake by 75% through microbial grazing under controlled experimental conditions. Bonkowski et al.27 reported that soils inoculated with bacterivorous protists (Acanthamoeba castellanii) increased the phosphorus uptake in spruce seedlings by 30%, improved the mycorrhizal colonization in plant roots, and allowed more efficient phosphorus absorption through fungal networks. Another study conducted by Herdler et al.28 showed that inoculating the free-living amoebae into the rhizosphere of rice increased the root length and surface area in plants leading to improved phosphorus accumulation (25%). Protists also influence soil fertility by enhancing nitrogen fixation through bacterial and archaea interactions.29 A study conducted by Clarholm26 in nitrogen and phosphorus-deficient soils indicated that presence of protists increased the phosphorus solubilization by 40% via releasing bioavailable phosphorus through bacterial predation and increased nitrogen mineralization as ammonium (NH4+) excretion, resulting in 75% higher nitrogen uptake by plants in a rhizosphere study.

Plant growth

Protists, particularly microbe-consuming taxa such as cercozoan species, play a significant role in promoting plant growth by fostering beneficial interactions within the soil microbiome.4 Protists influence the rhizosphere microbiome, like Cercomonas lenta, which impacts rhizosphere bacterial communities by increasing the abundance of plant-beneficial bacteria like Pseudomonas and Sphingomonas, and reducing potentially antagonistic taxa such as Chitinophaga. These interactions enhanced the key processes such as biofilm formation, nutrient solubilization, and rhizosphere colonization, resulting in improved plant performance. Inoculation of C. lenta in cucumber plants increased the biomass by 92% in a rhizosphere study which linked to enhanced phosphate solubilization and suppression of antagonistic bacteria. This demonstrates the potential of protists as biological agents in sustainable agriculture to stimulate plant-beneficial microbial consortia and improve nutrient availability and plant health.9,30 It plays a crucial role in soil diversity, with communities that vary across soil types, plant species, and environmental conditions. Studies have demonstrated that inclusion of organic manures and biofertilizers significantly enhanced the crop yields, correlating with pronounced shifts in protistan communities.31 The protists contribute to plant performance through several mechanisms like enhancing nutrient turnover, suppressing plant pathogens like Fusarium, and promoting plant-beneficial microorganisms such as Trichoderma, Pseudomonas, and Aspergillus.9 Protists excrete ammonia (NH4+) in a plant assimilable form and stimulate nutrient input by acting as carbon fixers and releasing after prey of N.32 Rice roots attract protists, which increased the nutrient solubility and availability by modulating the rhizosphere microbes.33 Recent research information on protists as predators of selective rhizosphere bacteria and fungi indicates its impact on modulating the plant growth promoting microbial communities.32,34

In the rhizosphere, bacterivorous protists, such as Acanthamoeba castellanii, enhanced the plant growth by regulating the bacterial microbiome and influencing the nutrient availability. Additionally, soil protists interact with mycorrhizal fungi, improving phosphorus acquisition and root architecture. Greenhouse experiments with cercozoan taxa like Cercomonas lenta and Cercomonas S24D2 showed a significant increase in plant biomass with their effects amplified in the presence of beneficial fungi like Trichoderma.3 The co-inoculation of heterotrophic protists and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) such as Azospirillum sp. demonstrated a synergistic effect on early rice plant growth in sterilized soil. Protists enhanced the survival of PGPR, significantly improving plant biomass (155.1%) and nitrogen uptake (226.0%).35 Qihui et al.36 states that the interaction between protists and Bacillus reshaped rhizosphere bacterial communities, increasing the tomato’s fresh weight, dry weight, and plant height. High-throughput sequencing revealed that protists altered the indigenous bacterial community, benefiting specific genera like Azospirillum and Massilia while reducing others. These findings highlighted the potential of leveraging protists as sustainable biofertilizers to manipulate soil microbiomes and improve agricultural productivity in an environmental friendly manner. Table 1 represents the role of different protists species in plant growth promotion.

Table (1):

Different species of protists in soil and its role in plant growth promotion

Protozoan Species |

Host Plants |

Associated Bacteria |

Root Structure Modification |

Increased biomass |

Shift in Bacterial Community |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Vermamoeba vermiformis, Naegleria sp., Colpoda steinii, Heteromita globosa |

Oryza sativa |

Azospirillum sp. B510 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

35 |

Acanthamoeba castellani |

Arabidopsis thaliana |

Native soil bacterial community |

Yes |

Yes |

ND |

37 |

Cercozoan protists |

Cucumis sativus |

Trichoderma, Plant-beneficial microorganisms |

Yes |

ND |

Yes |

3 |

Cercomonas lenta |

Cucumis sativus |

Pseudomonas, Sphingomonas, Chitinophaga |

ND |

Yes |

Yes |

30 |

Cercomonas longicauda, Tetrahymena pyriformis, Acanthamoeba polyphaga |

Zea mays |

Native soil bacterial community |

ND |

Yes |

Yes |

38 |

Disease suppression

Protists play a critical role in disease suppression within the soil microbiome, functioning as key regulators of soil health and plant pathogen control.

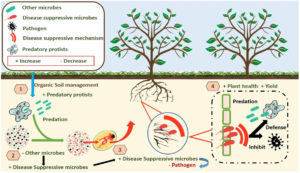

Mechanisms of suppression

Their ability to increase soil borne pathogen suppressiveness is attributed to their predatory behavior, which regulates populations of pathogenic microorganisms while fostering beneficial microbial communities.6 Studies have highlighted the association between protist activity and improved nutrient cycling, which indirectly supports plant defense mechanisms. Furthermore, protists contribute to the establishment of disease-suppressive soils by influencing soil moisture and nutrient availability. Specific soil microbiomes enriched with protists have been shown to suppress pathogens like Fusarium and Rhizoctonia solani through microbial predation and the induction of plant systemic resistance39 (Figure 2). These suppressive effects are often linked to complex soil legacies and manipulations, such as crop rotations and organic amendments, which enhanced the soil’s capacity to sustain a diverse and functional microbiome.

Experimental evidence of suppression

The suppressive mechanisms are supported by direct experimental evidences from various studies. For instance, Naegleria altered the rhizosphere bacterial community across tomato growth stages, increasing beneficial bacteria like Pseudomonas and reducing Ralstonia solanacearum.40 Similarly, addition of Cercomonas lenta along with poultry manure suppressed the Fusarium oxysporum by 85% while increasing the density of Bacillus.41 The suppression of Rhizoctonia solani has been linked to an increased presence of pathogen-suppressing microorganisms,42 while Pythium ultimum is controlled through the biosynthesis of extracellular secondary compounds by Pseudomonas fluorescens.43 Additionally, amoebae species have been found to produce extracellular secondary compounds that suppress Xanthomonas oryzae pathovars oryzae and oryzicola,44 and protists directly consume Ralstonia solanacearum, reducing its prevalence.30 These interactions demonstrate the potential of protists as natural disease suppressors, contributing to sustainable agricultural practices by promoting healthier soils and reducing reliance on chemical pesticides.

Interaction of soil protists with other microorganisms

In soil ecosystems, bacteria-feeding protists play a crucial regulatory role in shaping microbial communities. They exert predation pressure that act as a significant selective force driving bacterial evolution and adaptation. Unlike aquatic environments, soil protists operate within a complex spatial structure that influences predator-prey dynamics. Ronn et al.45 used advanced molecular tools to study soil bacterial communities and found the absence of grazing-resistant filamentous forms common in aquatic systems, suggesting distinct evolutionary adaptations in soil environments. In response to protist predation, bacteria have developed various defense mechanisms, including the production of toxic compounds46-49 and antibiotic-resistant systems.17 For example, Chromobacterium violaceum produces a quorum-sensing-regulated toxic pigment called violacein to evade predation,50 while Pseudomonas fluorescens responds to grazing by Naegleria americana by upregulating lipopeptide and putrescine biosynthesis,51 highlighting specific adaptations in competitive rhizosphere environment.

Advanced molecular techniques such as fluorescent in situ hybridization, stable isotope probing, metagenomics, phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis, and 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing have provided insights into these interactions.52-54 PLFA analysis indicates that Gram-positive bacteria, particularly Arthrobacter spp., tend to increase in response to protist grazing, whereas Gram-negative bacteria often decline,45,55 suggesting that the complex cell-wall structure of Gram-positive bacteria makes them less suitable as a food source. However, some Gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas spp., resist protist grazing.45 Protists also influence fungi and other microbial groups within the soil microbiome. They can indirectly promote fungal colonization of plant roots by modifying bacterial communities that interact with mycorrhizal fungi. Furthermore, predatory protists can alter competitive interactions between bacteria and fungi, enabling beneficial fungal taxa to thrive.8 It additionally affect the presence of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), which are predominantly found in the Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes phyla. Protist inoculation has been shown to enhance the survival of Azospirillum sp. (B510), a beneficial nitrogen-fixing bacterium, promoting its positive effects on rice growth by enhancing nitrogen mineralization and increasing bacterial genes involved in nitrogen cycling processes such as dissimilatory nitrate reduction and nitrate assimilation.35

Methodological approaches for studying soil protists

Advancements in molecular techniques have significantly improved the study of soil protists, revealing their vast taxonomic and functional diversity. High-throughput sequencing methods, such as targeting hyper-variable regions of 18S rRNA gene like V4 and V9, have revolutionized protist diversity surveys.56 Beyond these, meta-transcriptomics has emerged as a powerful approach for analyzing metabolically active protist communities by sequencing small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) transcripts, providing deeper insights into community composition.57

The use of multiple primer sets for metabarcoding has further enhanced taxonomic resolution, minimize biases in protist richness assessments.58 Metagenomics, which sequences entire genomic content without PCR amplification, allows functional profiling of protist communities, unveiling their metabolic potential and interactions with other microorganisms.59 Additionally, full-length 18S rRNA gene sequencing using long-read technologies has improved taxonomic resolution and species identification.60 Hybrid methodologies that combine culture-dependent and molecular approaches are also being adopted to validate the findings and minimize sequencing biases.61 Furthermore, advancements in bioinformatics pipelines are streamlining the analysis of large datasets, enabling more precise phylogenetic and ecological interpretations.62 These integrated molecular approaches are transforming the understanding of soil protists, their ecological roles, and responses to environmental changes. Figure 3 illustrates the Molecular Strategies for Soil protist analysis.

Applications of soil protists in sustainable agriculture

Soil protists play a crucial role in sustainable agriculture by enhancing plant growth, improving soil health, and suppressing plant diseases (Table 2). They contribute to increased nutrient uptake and boost crop yields by facilitating the release of essential nutrients through microbial interactions.63 Their role in maintaining soil health is equally significant, as they improve microbial diversity and accelerate organic matter decomposition, leading to better soil structure and fertility.18 Additionally, protists help suppress phytopathogens by reducing harmful microbial populations while promoting beneficial microbes that enhanced the plant resilience. Natural biocontrol agents support the growth of beneficial bacteria such as Pseudomonas and Bacillus, which further aid in disease suppression and nutrient solubilization.41 By integrating protists into farming systems, eco-friendly agricultural practices can be promoted, reducing reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides while ensuring long-term soil sustainability and improved the crop productivity.44

Table (2):

Role of protists in Sustainable Agriculture

| Protist Group | Example Species | Role in Sustainable Agriculture | Key Benefits/Impacts | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterivorous Protists | Acanthamoeba castellanii | Enhances nutrient mineralization | Increases soil nitrogen and phosphorus availability | 26,27 |

| Colpoda steinii | Facilitates bacterial transport within the rhizosphere | Improves bacterial colonization and nitrogen fixation | 24 | |

| Fungivorous Protists | Cercomonas lenta | Suppresses fungal pathogens like Fusarium | Enhances plant resistance and soil suppressiveness | 39 |

| Naegleria sp. | Alters rhizosphere microbiome, reducing pathogenic bacteria | Reduces Ralstonia solanacearum populations in tomato | 40 | |

| Mixotrophic Protists | Chlorophyta | Photosynthesis and organic matter decomposition | Contributes to carbon cycling and soil fertility | 18 |

| Pathogenic Protists | Pythium spp. | Increases with chemical fertilizer | Protist infections may negatively impact plant health if unmanaged | 22 |

| Protist Interactions with PGPR | Cercomonas longicauda | Synergizes with Azospirillum sp., improving nitrogen uptake | Increases plant biomass by 150% | 35 |

| Protists in Soil Health & Biofertilization | Rhizaria, Alveolata, Stramenopiles | Enhance microbial turnover to solubilize nutrients and support beneficial microbial communities | Enhances overall soil health, improves soil structure, reduces harmful microbes, and promotes plant growth | 22,64 |

| Protists in Disease Suppression | Cercomonas lenta | Suppresses Fusarium oxysporum | Reduces fungal pathogen prevalence up to 85% | 41 |

Challenges

Despite significant progress, the study of soil protists faces numerous challenges. Primer biases and amplification errors in high-throughput sequencing lead to incomplete or inaccurate representation of protist diversity.65 The lack of comprehensive and curated genetic reference databases further complicates taxonomic assignments, leaving many sequences unidentified.66 Moreover, functional interpretations of molecular data remain limited, as many protists’ ecological roles and interactions are poorly understood. Technical difficulties in isolating and culturing novel taxa restrict experimental validation of molecular findings. Despite these advancements, several technical challenges remain unanswered. Primer bias can skew metabarcoding results due to preferential amplification of certain taxa, leading to under representation of others.58,65 Sequencing limitations also pose issues, as short-read technologies may fail to distinguish closely related species, while long-read methods, though more precise, are often costly and less accessible.59,66 Additionally, many protist sequences lack reference genomes, making functional predictions uncertain and hindering accurate ecological interpretations.65 These limitations underscore the need for integrative approaches that combine molecular data with ecological and morphological studies to elucidate the multifaceted roles of protists in soil ecosystems.9

Soil protists are vital components of soil ecosystems, playing crucial roles in nutrient cycling, microbial regulation, and pathogen suppression, contributing significantly to soil fertility and plant health. Their diverse interactions within the soil microbiome enhance nutrient availability, promote beneficial microbial populations, and suppress plant pathogens naturally. Despite their ecological importance, challenges such as cultivation difficulties and limited taxonomic characterization restricted their agricultural application. However, recent advances in molecular techniques, including high-throughput sequencing and metagenomics, have expanded our understanding on protist diversity and function.

Therefore, integrating protists into sustainable agriculture through organic manures and microbiome management certainly improves soil health and crop productivity. This approach directly supports broader sustainability goals by reducing reliance on synthetic chemical inputs and enhancing the long-term resilience of agroecosystems.

Future research must focus on optimizing protist-based biofertilizers, exploring synergistic interactions with bacteria and fungi, and identifying key taxa that influence plant growth, yield, and resilience to abiotic stresses such as drought and salinity. The application ofartificial intelligence and machine learning aid in deciphering complex protist dynamics in soil ecosystems. Overcoming existing research challenges will enable better utilization of protists in enhancing soil resilience. Their application in agroecosystems holds greater promise for sustainable food production. Unlocking the full potential of soil protists revolutionizes eco-friendly, sustainable soil fertility and plant nutrition.

Future perspectives

Future research on soil protists will focus on their potential applications in sustainable agriculture, particularly in enhancing soil fertility and plant health. Developing effective methods for large-scale production and application of beneficial protists as biofertilizers and biocontrol agents could revolutionize soil management practices and improve plant nutrition. Advances in molecular techniques, including metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, and proteomics, are expected to uncover the functional roles of protists in nutrient cycling and microbial interactions. Future advancements will also aim to bridge knowledge gaps by linking taxonomic diversity with functional traits. Efforts to develop more universal primers and expand genetic reference databases are essential to overcome current biases and enhance accuracy in diversity assessments. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are anticipated to play vital roles in analyzing complex datasets, predicting protist functions, and modeling ecosystem-level interactions. Understanding the mechanisms through which protists influence root exudation, auxin signaling, and plant nutrient uptake will further clarify their contributions to crop resilience. Their role in mitigating stress under drought, salinity, and heavy metal contamination also requires deeper exploration. Long-term field studies are necessary to evaluate the impact of protist-driven microbial shifts on soil health and agricultural productivity. Additionally, protists show promise as bioindicators for soil quality monitoring and pollution assessment in precision agriculture. Collaborative research among molecular biologists, ecologists, and taxonomists will be the key to leveraging the full potential of protists in ecosystem management. Policy support for the adoption of protist-based technologies can promote their integration into sustainable farming systems. Ultimately, harnessing soil protists offers innovative and eco-friendly solutions to support global food security and environmental sustainability.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful to the Department of Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, India, for providing the necessary facilities to carry out this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Not applicable.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Chandarana KA, Amaresan N. Soil protists: an untapped microbial resource of agriculture and environmental importance. Pedosphere. 2022;32(1):184-197.

Crossref - Liao H, Hao X, Li Y, et al. Protists regulate microbially mediated organic carbon turnover in soil aggregates. Glob Chang Biol. 2024;30(1):e17102.

Crossref - Guo S, Xiong W, Hang X, et al. Protists as main indicators and determinants of plant performance. Microbiome. 2021;9(1):61.

Crossref - Feng B, Chen L, Lou J, et al. Rhizosphere Cercozoa reflect the physiological response of wheat plants to salinity stress. Soil Ecol Lett. 2025;7(1):240268.

Crossref - Fournier B, Steiner M, Brochet X, et al. Toward the use of protists as bioindicators of multiple stresses in agricultural soils: a case study in vineyard ecosystems. Ecol Indic. 2022;139:108955.

Crossref - Ren P, Sun A, Jiao X, et al. Predatory protists play predominant roles in suppressing soil-borne fungal pathogens under organic fertilization regimes. Sci Total Environ. 2023;863:160986.

Crossref - Fahma TLN, Cahyani NKD, Jumari, Hariyati R, Soeprobowati TR. Environmental DNA Approach to Identify Protists Community in Sediment of Balekambang Lake, Indonesia, Using 18S rRNA Gene. In: Haddout S, Priya K, Hoguane AM. (eds) Proceedings of The 2nd International Conference on Climate Change and Ocean Renewable Energy. CCORE 2022. Springer Proceedings in Earth and Environmental Sciences. Springer, Cham. 2024.

Crossref - Ceja-Navarro JA, Wang Y, Ning D, et al. Protist diversity and community complexity in the rhizosphere of switchgrass are dynamic as plants develop. Microbiome. 2021;9(1):96.

Crossref - Geisen S, Mitchell EAD, Adl S, et al. Soil protists: a fertile frontier in soil biology research. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2018;42(3):293-323.

Crossref - Wang H, Jiang L, Weitz JS. Bacterivorous grazers facilitate organic matter decomposition: a stoichiometric modeling approach. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2009;69(2):170-179.

Crossref - Wang B, Chen C, Xiao YM, et al. Trophic relationships between protists and bacteria and fungi drive the biogeography of rhizosphere soil microbial community and impact plant physiological and ecological functions. Microbiol Res. 2024;280:127603.

Crossref - Singer D, Seppey CVW, Lentendu G, et al. Protist taxonomic and functional diversity in soil, freshwater and marine ecosystems. Environ Int. 2021;146:106262.

Crossref - Najarro, Melodie C. pH Influences the Thermal Performance Curves of Protist Populations. Master’s thesis, Duke University, 2024. https://hdl.handle.net/10161/30999

- Yim B, Ibrahim Z, Ruger L, et al. Soil texture is a stronger driver of the maize rhizosphere microbiome and extracellular enzyme activities than soil depth or the presence of root hairs. Plant Soil. 2022;478(1):229-251.

Crossref - Xue Y, Liu M, Chen H, et al. Microbial hierarchical correlations and their contributions to carbon-nitrogen cycling following a reservoir cyanobacterial bloom. Ecol Indic. 2022;143:109401.

Crossref - Nguyen BAT, Dumack K, Trivedi P, Islam Z, Hu HW. Plant associated protists-Untapped promising candidates for agrifood tools. Environ Microbiol. 2023;25(2):229-240.

Crossref - Nguyen BAT, Chen QL, He JZ, Hu HW. Microbial regulation of natural antibiotic resistance: understanding the protist-bacteria interactions for evolution of soil resistome. Sci Total Environ. 2020;705:135882.

Crossref - Gurau S, Imran M, Ray RL. Algae: a cutting-edge solution for enhancing soil health and accelerating carbon sequestration-a review. Environ Technol Innov. 2024;37:103980.

Crossref - Geisen S, Hu S, dela Cruz TEE, Veen G. Protists as catalyzers of microbial litter breakdown and carbon cycling at different temperature regimes. ISME J. 2021;15(2):618-621.

Crossref - Seppey CV, Singer D, Dumack K, et al. Distribution patterns of soil microbial eukaryotes suggests widespread algivory by phagotrophicprotists as an alternative pathway for nutrient cycling. Soil Biol Biochem. 2017;112:68-76.

Crossref - Jousset A. Application of protists to improve plant growth in sustainable agriculture. In: Rhizotrophs: Plant Growth Promotion to Bioremediation. 2017:263-273.

Crossref - Xiong W, Jousset A, Guo S, et al. Soil protist communities form a dynamic hub in the soil microbiome. ISME J. 2018;12(2):634-638.

Crossref - Hawxhurst CJ, Micciulla JL, Bridges CM, Shor M, Gage DJ, Shor LM. Soil protists can actively redistribute beneficial bacteria along Medicago truncatula roots. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2023;89(3):e01819-22.

Crossref - Micciulla JL, Shor LM, Gage DJ. Enhanced transport of bacteria along root systems by protists can impact plant health. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2024;90(4):e02011-23.

Crossref - Gao Z, Karlsson I, Geisen S, Kowalchuk G, Jousset A. Protists: puppet masters of the rhizosphere microbiome. Trends Plant Sci. 2019;24(2):165-176.

Crossref - Clarholm M. Interactions of bacteria, protozoa and plants leading to mineralization of soil nitrogen. Soil Biol Biochem. 1985;17(2):181-187.

Crossref - Bonkowski M, Jentschke G, Scheu S. Contrasting effects of microbial partners in the rhizosphere: interactions between Norway Spruce seedlings (Picea abies Karst.), mycorrhiza (Paxillus involutus (Batsch) Fr.) and naked amoebae (protozoa). Appl Soil Ecol. 2001;18(3):193-204.

Crossref - Herdler S, Kreuzer K, Scheu S, Bonkowski M. Interactions between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomus intraradices, Glomeromycota) and amoebae (Acanthamoeba castellanii, Protozoa) in the rhizosphere of rice (Oryza sativa). Soil Biol Biochem. 2008;40(3):660-668.

Crossref - Wang L, Ji J, Zhou F, et al. Soil bacterial and protist communities from loquat orchards drive nutrient cycling and fruit yield. Soil Ecol Lett. 2024;6(4):240232.

Crossref - Guo S, Geisen S, Mo Y, et al. Predatory protists impact plant performance by promoting plant growth-promoting rhizobacterial consortia. ISME J. 2024;18(1):wrae180.

Crossref - Liu C, Zhou Z, Sun S, et al. Investigating protistan predators and bacteria within soil microbiomes in agricultural ecosystems under organic and chemical fertilizer applications. Biol Fertil Soils. 2024;60(7):1009-1024.

Crossref - Santoyo G, del Carmen Orozco-Mosqueda M, Babalola OO. How protists contribute to plant growth and health: Exploring new interactions with the plant microbiome. The Microbe. 2025;7:100361.

Crossref - Murase J, Asiloglu R. Protists: the hidden ecosystem players in a wetland rice f ield soil. Biol Fertil. Soils,2024;60(6):773-787.

Crossref - Asiloglu R, Bodur SO, Samuel SO, Aycan M, Murase J, Harada N. Trophic modulation of endophytes by rhizosphere protists. ISME J. 2024;18(1):wrae235.

Crossref - Asiloglu R, Shiroishi K, Suzuki K, Turgay OC, Murase J, Harada N. Protist-enhanced survival of a plant growth promoting rhizobacteria, Azospirillum sp. B510, and the growth of rice (Oryza sativa L.) plants. Appl Soil Ecol. 2020;154:103599.

Crossref - Qihui L, Chen L, Ying G, et al. Combined application of protist and Bacillus enhances plant growth via reshaping rhizosphere bacterial composition and function. Pedosphere. 2024;34(5):1567-1580.

- Krome K. Interactions in the rhizosphere: plant responses to bacterivorous soil protozoa. PhD dissertation. Technische Universitat Darmstadt. 2008.

Crossref - Kuppardt A, Fester T, Hartig C, Chatzinotas A. Rhizosphere protists change metabolite profiles in Zea mays. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:857.

Crossref - Guo S, Jiao Z, Yan Z, et al. Predatory protists reduce bacteria wilt disease incidence in tomato plants. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):829.

Crossref - Song Y, Liu C, Yang K, et al. Predatory protist promotes disease suppression against bacterial wilt through enriching plant beneficial microbes at the early stage of plant growth. Plant Soil. 2024;11(1):1241-1252.

Crossref - Guo S, Tao C, Jousset A, et al. Trophic interactions between predatory protists and pathogen-suppressive bacteria impact plant health. ISME J. 2022;16(8):1932-1943.

Crossref - Fujino M, Bodur SO, Harada N, Asiloglu R. Guardians of plant health: roles of predatory protists in the pathogen suppression. Plant Soil. 2024;509(1):5-13.

Crossref - Weidner S, Latz E, Agaras B, Valverde C, Jousset A. Protozoa stimulate the plant beneficial activity of rhizospheric pseudomonads. Plant Soil. 2017;410(1-2):509-515.

Crossref - Long JJ, Jahn CE, Sanchez-Hidalgo A, et al. Interactions of free-living amoebae with rice bacterial pathogens Xanthomonas oryzae pathovar soryzae and oryzicola. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202941.

Crossref - Ronn R, McCaig AE, Griffiths BS, Prosser JI. Impact of protozoan grazing on bacterial community structure in soil microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68(12):6094-6105.

Crossref - Jousset A, Lara E, Wall LG, Valverde C. Secondary metabolites help biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 to escape protozoan grazing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(11):7083-7090.

Crossref - Jousset A, Scheu S, Bonkowski M. Secondary metabolite production facilitates establishment of rhizobacteria by reducing both protozoan predation and the competitive effects of indigenous bacteria. Funct Ecol. 2008;22(4):714-719.

Crossref - Pedersen AL, Ekelund F, Johansen A, Winding A. Interaction of bacteria-feeding soil flagellates and Pseudomonas spp. Biol Fertil Soils. 2010;46(2):151-158.

Crossref - Pedersen AL, Winding A, Altenburger A, Ekelund F. Protozoan growth rates on secondary-metabolite-producing Pseudomonas spp. correlate with high-level protozoan taxonomy. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;316(1):16-22.

Crossref - Matz C, Deines P, Boenigk J, et al. Impact of violacein-producing bacteria on survival and feeding of bacterivorous nanoflagellates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(3):1593-1599.

Crossref - Song C, Mazzola M, Cheng X, et al. Molecular and chemical dialogues in bacteria-protozoa interactions. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12837.

Crossref - Wagner M, Nielsen PH, Loy A, Nielsen JL, Daims H. Linking microbial community structure with function: fluorescence in situ hybridization-microautoradiography and isotope arrays. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006;17(1):83-91.

Crossref - Willers C, Jansen van Rensburg P, Claassens S. Phospholipid fatty acid profiling of microbial communities-a review of interpretations and recent applications. J Appl Microbiol. 2015;119(5):1207-1218.

Crossref - Liehr T. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH). Springer. 2017.

Crossref - Hunninghaus M, Koller R, Kramer S, Marhan S, Kandeler E, Bonkowski M. Changes in bacterial community composition and soil respiration indicate rapid successions of protistgrazers during mineralization of maize crop residues. Pedobiologia. 2017;62:1-8.

Crossref - Del Campo J, Guillou L, Hehenberger E, Logares R, Lopez-Garcia P, Massana R. Ecological and evolutionary significance of novel protist lineages. Eur J Protistol. 2016;55(Pt A):4-11.

Crossref - Kolisko M, Flegontova O, Karnkowska A, et al. EukRef-excavates: seven curated SSU ribosomal RNA gene databases. Database (Oxford). 2020;2020:baaa080.

Crossref - Fiore-Donno AM, Richter-Heitmann T, Bonkowski M. Contrasting responses of protistan plant parasites and phagotrophs to ecosystems, land management and soil properties. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1823.

Crossref - Geisen S, Laros I, Vizcaino A, Bonkowski M, De Groot G. Not all are free-living: High-throughput DNA metabarcoding reveals a diverse community of protists parasitizing soil metazoa. Mol Ecol. 2015;24(17):4556-4569.

Crossref - Jamy M, Foster R, Barbera P, et al. Long read metabarcoding of the eukaryotic rDNA operon to phylogenetically and taxonomically resolve environmental diversity. Mol Ecol Resour. 2020;20(2):429-443.

Crossref - Lax G, Eglit Y, Eme L, et al. Hemimastigophora is a novel supra-kingdom-level lineage of eukaryotes. Nature. 2018;564(7736):410-414.

Crossref - Mahe F, de Vargas C, Bass D, et al. Parasites dominate hyperdiverse soil protist communities in Neotropical rainforests. Nat Ecol Evol. 2017;1(4):0091.

Crossref - Neher DA. Moving up within the soil food web: protists, nematodes, and other microfauna. In: Uphoff N, D’Alessandro A, Bodhankar S, et al, eds. Biological Approaches to Regenerative Soil Systems. CRC Press. 2023:157-168.

Crossref - Lin C, Li WJ, Li LJ, Neilson R, An XL, Zhu YG. Movement of protistan trophic groups in soil-plant continuums. Environ Microbiol. 2023;25(11):2641-2652.

Crossref - Mau RL, Hayer M, Purcell AM, Geisen S, Hungate BA, Schwartz E. Measurements of soil protist richness and community composition are influenced by primer pair, annealing temperature, and bioinformatics choices. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2024;90(7):e00800-24.

Crossref - Pawlowski J, Audic S, Adl S, et al. CBOL protist working group: barcoding eukaryotic richness beyond the animal, plant, and fungal kingdoms. PLoS Biol. 2012;10(11):e1001419.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.