ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

The contamination of food products by psychrotrophic microorganisms, particularly Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), presents a significant challenge to food quality and safety in the dairy industry. Although not a foodborne pathogen, P. aeruginosa is highly destructive to food stability, leading to spoilage and reduced shelf life. This study investigates the interactions between P. aeruginosa, several foodborne pathogens, yogurt starter cultures, and spoilage fungi using dual-culture assays. P. aeruginosa exhibited strong antagonistic effects on various microorganisms and demonstrated inhibition of pathogens through metabolic compounds such as hydroxyurea, pentane-1, 5-diol, ethylmethylsilane, and N-benzylidene-dimethylammonium chloride, identified via GC-MS analysis. To counteract P. aeruginosa, the protective lactic acid bacterium Limosilactobacillus reuteri (L. reuteri) was employed. The bacterium enhanced the sensitivity of P. aeruginosa to several antibiotic classes, including aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, cephalosporins, and chloramphenicol. GC-MS profiling of L. reuteri extracts revealed potent bioactive compounds, such as derivatives of D-lactic acid, phenyllactic acid, and hydroxyisocaproic acid, which possess robust antimicrobial properties. When applied in fermented milk, L. reuteri extracts (2 mg/mL) completely inhibited the growth of P. aeruginosa while preserving the functionality of yogurt starter cultures during storage. These findings highlight the potential of L. reuteri as a bio-protective agent to mitigate spoilage in dairy products.

Limosilactobacillus reuteri, In Vitro Study, Dual Culture, Antibacterial Activity, Modified Antibiotic Susceptibility, Pseudomonas Spoilage of Dairy Products

Food contamination by psychrotrophic bacteria, particularly Pseudomonas aeruginosa, represents a significant challenge in the dairy industry, undermining both food quality and safety. Although not classified as a foodborne pathogen, P. aeruginosa is a destructive microorganism capable of causing spoilage that affects the structural stability, color, flavor, and overall acceptability of dairy products during storage.1,2 The economic and operational implications of such spoilage are considerable, leading to increased product waste, reduced shelf life, and diminished consumer trust. Furthermore, the growing prevalence of multidrug-resistant strains of P. aeruginosa exacerbates the threat, particularly as contamination is often introduced at multiple points in the dairy production chain. From water sources and milking equipment to cooling tanks and raw milk, the dairy farm environment provides numerous opportunities for the proliferation and spread of this microorganism.3,4

Contamination by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is of particular concern in dairy processing due to its ability to thrive in cold temperatures and its resistance to various sanitization methods.3,5 Once present, the organism can disrupt microbial ecosystems, especially in products reliant on fermentation. This spoilage mechanism occurs not only because of P. aeruginosa’s rapid growth but also due to the production of metabolites that interfere with the activity of starter cultures such as Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus. These starter cultures play an essential role in the production of yogurt and other fermented dairy products, and any disruption can lead to reduced product quality and compromised fermentation efficiency.1

Interestingly, P. aeruginosa exhibits antagonistic behavior toward other microorganisms, including both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. It produces various bioactive compounds, such as pyocyanin, hydroxyurea, and rhamnolipids, which have antimicrobial properties that inhibit the growth of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, as well as fungi.6,7 While this antagonistic capacity has been extensively studied in clinical and environmental microbiology, its role within the dairy microbiota remains underexplored. Understanding the dynamics of P. aeruginosa in polymicrobial environments is crucial for managing its impact, particularly as it is often co-isolated with other pathogens and spoilage organisms.8 However, not all strains of P. aeruginosa exhibit consistent antagonistic behavior, indicating the need for further characterization of its interactions with other microorganisms.9,10

Current research has largely focused on the prevalence of P. aeruginosa in dairy farms, its incidence in milk and dairy products, and its resistance to antibiotic treatments.4 However, less attention has been paid to its interactions with beneficial microorganisms, particularly starter cultures that are critical for fermentation. Such polymicrobial interactions can influence the stability and quality of fermented dairy products, making it essential to explore methods for controlling P. aeruginosa without disrupting the activity of desirable bacteria.5

To address this challenge, the use of protective microorganisms, such as lactic acid bacteria (LAB), has emerged as a promising biocontrol strategy. Among these, Limosilactobacillus reuteri has shown considerable potential due to its ability to produce a range of antimicrobial metabolites, including lactic acid derivatives, phenyllactic acid, and other volatile organic compounds.11 These bioactive compounds can inhibit the growth of spoilage microorganisms like P. aeruginosa while preserving the functionality of starter cultures. Additionally, L. reuteri has been shown to enhance the sensitivity of P. aeruginosa to various classes of antibiotics, making it a viable candidate for mitigating the organism’s multidrug-resistance.12

Therefore, this study explores the intricate interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa, dairy starter cultures, and foodborne pathogens within a polymicrobial environment. It further evaluates the potential of Limosilactobacillus reuteri as a bioprotective agent to inhibit P. aeruginosa and mitigate its adverse effects on fermentation. Using GC-MS profiling, the bioactive metabolites produced by L. reuteri are analyzed to uncover their role in its antimicrobial activity.

Pathogenic and spoilage strains

Escherichia coli (E. coli) strain E11 (accession number KY780346.1), Salmonella enterica (S. enterica) strain SA19992307 (accession number CP030207.1), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) strain Kasamber5 (accession number KY549641.1), Bacillus cereus (B. cereus) strain 151007-R3-K09-40-27F (accession number KY820914.1) were isolated and identified by Al-Gamal et al.13 Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes); Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) ATCC 6538 strains were supplemented from the collection of Dairy Microbiological Lab., NRC, Egypt, while Aspergillus flavus (Asp. flavus) 3357 and Candida albicans ATCC 10231 were provided by colleagues of the marine toxin lab., NRC, Egypt.

Bio-protective lactic acid bacterium and Starter

Limosilactobacillus reuteri NRRL B-14171 as well as yogurt starter (Streptococcus thermophilus Chr-1 and Lactobacillus bulgaricus Lb-12) were obtained from collection of Dairy Microbiological Lab., NRC, Egypt.

Investigating the antagonism of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Interaction via dual culture assay

The antagonistic interaction was inducted between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and several indicators including pathogenic and food spoilage strains, as well as dairy starters. The interaction was performed via neighboring dual plate assay that developed the method described by Baptista et al.14 Agar plates were swabbed from 0.5 McFarland of bacterial suspension. Then, the central well (1 cm) was filled with nutrient agar seeded with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (108 CFU).

Extraction of bioactive compounds

Heavily-streaked Pseudomonas aeruginosa was grown on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) at 32 °C for 24 hours. Bioactive compounds were extracted as described by Muller and Merrett,15 with slight modifications. Equal units (w/v) of the harvested TSA and Chloroform were mixed and agitated for an hour. The filtrate was concentrated in a fuming hood and stored in -20 °C till use.

Evaluation of the extract antimicrobial activity via disc diffusion

The antimicrobial activity of the crude extract is evaluated through disc diffusion assay as recommended in the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy guidelines.16 Respectively, Ciprofloxacin (5 µg) and Clotrimazole (1 mg/mL) was used as antibacterial and antifungal positive controls.

GC-MS profiling of both Limosilactobacillus reuteri and Pseudomonas extract

The analysis was performed in central laboratory, Food Industries and Nutrition Research Institute, National Research Centre, Dokki, Egypt using a GC-MS system (7890A-5975C, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Rosa, CA, USA) equipped with an HP-5 MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 mm, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Rosa, CA, USA). The injection volume of the sample was 1 µL. Helium (99.999%) was used as the carrier gas at a flow-rate of 1 mL/min. The temperature of the injection port was 280 °C, and the column temperature pro Gram was as follows: 40 °C for 5 min, followed by an increase to 150 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min, and an increase to 210 °C at the rate of 10 °C/min. The MS conditions Capillary column and 5975B Inert XL MS system under electron ionization at 70 eV and Quadrupole mass analyzer. The MS source and Quadrupole were held at 230 °C and 150 °C, respectively. Helium was used as carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The promising Cell-free Supernatant was analyzed on the Headspace-GC–MS instrumentation described with a headspace (HS) oven temperature of 80 °C. The HS loop and transfer line temperatures were set at 90 °C and 100 °C, respectively. Vial equilibration was set at 15 min. The vial pressurization was set at 15 psi for 0.15 min. Injection time was set at 0.50 min.

Evaluation of Limosilactobacillus reuteri role in controlling Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Interference with antibiotic susceptibility

Antibiotic sensitivity assay on m-Mueller Hinton agar was performed as described in British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC) guidelines.16 The m-Meuller Hinton agar plates were prepared by pouring a 1st MRS seeded with Limosilactobacillus reuteri.

Extraction of bioactive compounds

MRS broth (500 mL) was inoculated with Limosilactobacillus reuteri NRRL B-14171 and incubated at 30 °C. After 72 hours, MRS was mixed with Ethyl acetate: Diethyl ether (1:1) and vigorously shacked for an hour. The organic layer was separated and evaporated in fuming hood till dry film was obtained.17

Evaluation of the extract against both Pseudomonas aeruginosa and yogurt starter

In a dual culture (MRS broth) both of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (103 CFU/ml) and yogurt starter (106 CFU/mL) were inoculated. Different concentrations (0-2000 µg/mL) of L. reuteri extract were applied and microbial numbers were recorded after 24 hours incubation in refrigerator.

Evaluation of the preservative potential in a real dairy model

Manufacturing of set yogurt

A whole buffalo’s milk was subjected to heat treatment (85 °C/15 min) and inoculated with the commercial yogurt starter (2% v/v). The inoculated milk was divided into four batches; (1) Control (a batch that just contains yogurt starter), (2) Ps. (a batch that contains yogurt starter + 3 log CFU/mL of Pseudomonas aeruginosa), (3) re. (Batch No. 2 + 1% v/v of Limosilactobacillus reuteri), and (4) ext. (Batch No. 2 + 2 mg/mL of L. reuteri extract) (Table 1). After complete coagulation at 42 °C, the four batches were prepared for cold storage. Microbiological analyses investigated the total lactic acid bacteria (log CFU/g), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CFU/g), and Mold and yeast (CFU/g) for 0-15 days with 3 days interval.18

Table (1):

Different processes of set yogurt manufacturing

| Batch | Additives | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yogurt starter (2%) | L. reuteri (1% v/v) | Ps. aeruginosa (103 CFU/ml) | L. reuteri extract (2 mg/ml) | |

| Ps | √ | NA | √ | NA |

| Control | √ | NA | NA | NA |

| St/Ps/re | √ | √ | √ | NA |

| St/Ps/ex | √ | NA | √ | √ |

Microbiological analyses

Enumeration of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Enumeration was done on the Pseudomonas CN (Oxoid, England) agar.18 Inoculated plates were incubated at 25 °C for 48 hours.

Enumeration of total LAB on MRS

Enumeration of total lactic acid bacteria, including SLAB and NSLAB on MRS agar (Oxoid) for 48-72 hours at 37 °C.

Enumeration of molds and yeasts

Enumeration of Asp. flavus and Candida albicans were done on Potato dextrose agar (PDA), the inoculated plates were incubated at 20-25 °C for 5 days.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using Minitab 18. The means were determined by analysis of variance test (ANOVA, two-way analysis) (p < 0.05).

Estimating the antagonistic potential of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Dual cultures on agar plates

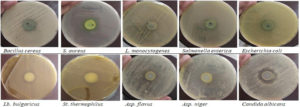

In dual cultures (multispecies interaction), the behavior of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (competition/co-operation) with different foodborne pathogens, yogurt starter; Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus, as well as some food spoilage and toxin-producing fungi has been assessed (Figure 1). Results were represented as inhibition diameter (mm) in Table 2. Presented zones of inhibition showed a general antagonistic behavior of Pseudomonas aeruginosa that began from 15.67 mm in case of Escherichia coli and reached 24.67 mm with Aspergillus niger. Except the unaffected Staphylococcus aureus, there is no significance response among the tested pathogenic bacteria (p < 0.05). Both of Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Aspergillus flavus seems to be the same and all of Streptococcus thermophilus, Aspergillus niger, and Candida albicans appear no significant differences (p < 0.05).

Table (2):

The estimated antagonism of Ps. aeruginosa in dual cultures on agar plates

| Indicator microorganism | Zone of inhibition (mm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pathogenic bacteria | Bacillus cereus | 16.17 ± 0.17C |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ND | |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 17.00 ± 0.59C | |

| Salmonella enterica | 16.00 ± 0.29C | |

| Escherichia coli | 15.67 ± 0.34C | |

| Yogurt starter | Lactobacillus bulgaricus | 19.17 ± 0.45B |

| Streptococcus thermophilus | 24.33 ± 0.90A | |

| Spoilage fungi | Aspergillus flavus | 20.67 ± 0.34B |

| Aspergillus niger | 24.67 ± 0.90A | |

| Candida albicans | 23.67 ± 0.90A | |

Means ± SE; Values that share the same letter have no significance

The same conclusion was attained by Toppo and Tiwari,19 when they subjected Pseudomonas spp. and Rhizoctonia soloni. Also, Rakh et al.20 reported a good inhibitory potential of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain against Sclerotium rolfsii (reduction by 94% of dry weight).

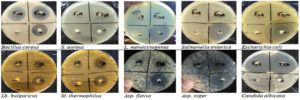

Disc diffusion of Chloroform extract

This test was performed to measure the contribution degree of Pseudomonas antimicrobial metabolism toward the same groups of microorganisms. Chloroform extract was prepared and tested via disc diffusion assay (Figure 2). Results were presented in comparison with positive controls (Table 3). Inhibition zone was the least with Staphylococcus aureus (8.67 mm) and gradually increased as 15 mm in case of Lactobacillus bulgaricus. All of Bacillus cereus (17.07 mm), Aspergillus niger (17 mm), and Streptococcus thermophilus (16.33 mm) were affected by the same degree without significance (p > 0.05). Inhibition reached the greatest with Candida albicans (40.67 mm). There is no detected inhibition in case of Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enterica, and Escherichia coli.

Table (3):

Estimated antimicrobial activity of Pseudomonas extract by disc diffusion assay

| Indicator microorganism | Zone of inhibition (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas extract | Positive control (CIP 5/Clotrimazole) | ||

| Pathogenic bacteria | Bacillus cereus | 17.07 ± 0.07Bb | 23.33 ± 0.34BCa |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 8.67 ± 0.34Eb | 22.5 ± 0.29Ca | |

| Listeria monocytogenes | ND | 32.5 ± 0.29A | |

| Salmonella enterica | ND | 33.33 ± 0.34A | |

| Escherichia coli | ND | 23.33 ± 0.34BC | |

| Yogurt starter | Lactobacillus bulgaricus | 15 ± 0.59Ca | 16.67 ± 0.68Ea |

| Streptococcus thermophilus | 16.33 ± 0.34Bb | 18.67 ± 0.34Da | |

| Spoilage fungi | Aspergillus flavus | 12.33 ± 0.34Db | 24.33 ± 0.34Ba |

| Aspergillus niger | 17 ± 1.02Ba | 16.33 ± 0.90Ea | |

| Candida albicans | 40.67 ± 0.34Aa | 14.67 ± 0.34Fb | |

Means ± SE; The same capital letters within the same column means no significance, while the same small letters within a raw indicates no significance; CIP 5 ciprofloxacin antibacterial; Clotrimazole antifungal agent

Figure 2. Estimated antimicrobial of Ps. aeruginosa extract against indicator organisms (disc diffusion technique)

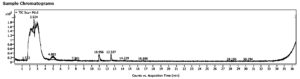

Metabolic profiling of P. aeruginosa extract (chloroform) by GC-MS

In a way to understand how different microorganisms were inhibited due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the later extract was scanned by GC-MS spectrometer as shown by Figure 3 and compounds were listed in Table 4. The most predominant; N-benzylidene-dimethylammonium chloride (area 12.82%) which has a reported activity as surfactant and antimicrobial, followed by the antimicrobial alcohol; Pentane-1,5-diol (area 4.5%), the antibacterial; Ethylmethylsilane (area 3.1%), and the antimicrobial; Hydroxyurea.

Table (4):

GC-MS profile of the most important bioactive compounds in Pseudomonas extract

RT |

Compound name |

Area% |

Biological activity |

|---|---|---|---|

2.312 |

Hydroxyurea |

0.28 |

Antimicrobial21 |

2.646 |

Pentane-1,5-diol |

4.5 |

Antibacterial, antifungal, anti-viral22 |

2.799 |

Ethylmethylsilane (silane derivatives) |

3.1 |

Antibacterial23 |

12.537 |

N-benzylidene-dimethyl-ammonium chloride |

12.82 |

Surfactant, antimicrobial24 |

Our current results came in agreement with previous studies like Amankwah et al.25 who reported the potential of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate to produce antimicrobial alcohols (Hexadecanol and Eicosanol), other like Zhou et al.26 and Deshmukh and Kathwate,27 to produce surfactants (Rhamnolipids).

Depending on GC-MS results, the wide spectrum antimicrobial effect of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its extract can be attributed minimally to Hydroxyurea which reported to kill Escherichia coli through inhibition of class I ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), depleting dNTP pools and leading to replication fork arrest.28 Maximum antimicrobial effect is attributed to all of Ethylmethylsilane which enhances the antimicrobial effect,23 Pentane-1,5-diol,22 and N-benzylidene-dimethylammonium chloride.29

Bio-protective role of Limosilactobacillus reuteri in the control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Interference with antibiotic susceptibility

This point evaluates the effect of Limosilactobacillus reuteri on Pseudomonas response toward different antibiotics. Five classes; aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, mono beta-lactams, chloramphenicol, and cephalosporins were represented as shown in Table 5. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was inhibited by all of Amikacin 30 µg (23.33 mm diameter), Cefepime 30 µg (28 mm), and Azetronam 10 µg (27.67 mm), while appeared not affected by Chloramphenicol 30 µg (7.67 mm) and Ampicillin 10 µg (6.67 mm). This response was reported by researches,30 which attributed this resistance to the MexXY multidrug efflux system that developed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Pre-hosting with Limosilactobacillus reuteri cells increased the zone of inhibition from 23.33 to 25.67 mm (Amikacin 30), 28 to 35.33 mm (Cefepime 30), 27.67 to 31.67 mm (Azetronam 10), 6.67 to 25.67 mm (Chloramphenicol 30), and 6.67 to 10.33 mm (Ampicillin 10). The effect of Limosilactobacillus reuteri seemed to inhibit the Pseudomonal-derived stress response systems by suppressing the system effluxes different classes of antibiotics; the MexXY system30 whose existence is necessary for the development of natural resistance to several classes of antibiotics.31

Table (5):

Influence of L. reuteri on the antibiotic susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

| Treatment | Diameter of inhibition (mm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amikacin 30 µg | Cefepime 30 µg | Chloramphenicol 30 µg | Ampicillin 10 µg | Azetronam 10 µg | |

| Class | aminoglycoside | beta-lactam | Chloramphenicol | Cephalosporin | Mono beta-lactam |

| Control | 23.33 ± 0.34B | 28 ± 0.00B | 7.67 ± 0.16B | 6.67 ± 0.17B | 27.67 ± 0.34B |

| Response | Sensitive | Sensitive | Resistant | Resistant | Sensitive |

| L. reuteri | 25.67 ± 0.34A | 35.33 ± 0.34A | 25.67 ± 0.34A | 10.33 ± 0.34A | 31.67 ± 0.34A |

| Response | Sensitive | Sensitive | Sensitive | Resistant | Sensitive |

Means ± SE; Values that share the same letter have no significance

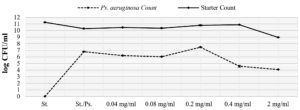

The impact of L. reuteri extract on growth of both Pseudomonas aeruginosa and yogurt starter

The active extract of L. reuteri was studied for its negative impact on both P. aeruginosa and yogurt starter and results were presented in Figure 4. There is a strong inhibition caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to yogurt starter whose count was reduced by at least one log cycle (90%). After the addition of L. reuteri extract, Pseudomonas aeruginosa was reduced from 6.79 to 6.21 log CFU/mL at 0.04 mg extract/mL (0.24 log cycle), 6.02 log CFU/mL at 0.08 mg extract/mL (0.77 log cycle), 4.58 log CFU/mL at 0.4 mg extract/mL (2.21 log cycles), and 4.09 log CFU/ml at 2 mg extract/mL (2.7 log cycles). On the other hand, yogurt starter increased gradually with the increasing in added extract concentration. Yogurt starter count increased from 10.29 log CFU/ml to 10.46, 10.36, 10.80, 10.88 log CFU/ml at extract concentrations 0.04, 0.08, 0.20, and 0.4 mg/mL. A relatively great drop was noted (from 10.29 to ~9 log CFU/ml) at 2 mg/ml of extract concentration.

Figure 4. Impact of L. reuteri extract on the growth of both Ps. aeruginosa and yogurt starter in dual culture

Metabolic profiling of the protective; L. reuteri bacterium using GC-MS analysis

Profiling of Limosilactobacillus reuteri extract by GC-MS (Figure 5) revealed predominance of D-Lactic acid derivative with area 35.87%, 1,3-Dioxolane-2-d, 2-methyl (Dioxolane derivative) with area 17.35%, Butanedioic acid, 2TMS derivative (area 4.87%), 2-Hydroxyisocaproic acid, deriva-tive (area 4%), 3-Phenyllactic acid derivative (area 1.39%), Butylated hydroxy toluene (0.93%) as presented in Table 6. After estimation of L. reuteri-based metabolic content, the observed inhibition of Pseudomonas growth can be understood. The inhibitory contents that produced by L. reuteri were majorly Lactic acid derivatives that widely reviewed as strong antimicrobial agents32 with broad-spectrum activity that was proven against Pseudomonas aeruginosa.11 Considerable contribution to the reduction of spoilage populations was attributed to 1,3-dioxolane derivatives which perfectly antagonized Pseudomonas aeruginosa as reported by both.33 Both of amino acid metabolites; 2-Hydroxyisocaproic acid and Phenyllactic acid were produced by Lactobacillus spp. and showed a reproducible antagonism against both pathogenic and spoilage bacteria, as well as spoilage and toxigenic fungi.34,35

Table (6):

GC-MS profile of the most important bioactive compounds in L. reuteri extract

RT |

Compound name |

Area% |

Biological activity |

|---|---|---|---|

2.532 |

1,3-Dioxolane-2-d, 2-methyl |

17.35 |

Antibacterial and antifungal33 |

3.564 |

D-Lactic acid derivatives |

35.87 |

Antimicrobial11 |

13.155 |

2-Hydroxyisocaproic acid, derivative |

4 |

Bactericidal and fungicidal34 |

14.448 |

Butanedioic acid, 2TMS derivative |

4.87 |

Flavoring agent36 |

18.654 |

3-Phenyllactic acid derivative |

1.39 |

Broad antimicrobial37 |

28.488 |

Butylated hydroxy toluene |

0.93 |

Antioxidant38 |

Applying the bio-preservation potential of Limosilactobacillus reuteri in Fermented milk

A whole buffalo’s milk was subjected to heat treatment (85 °C/15 min) and inoculated with the commercial yogurt starter (2% v/v). The inoculated milk was divided into four batches; (1) Control (untreated), (2) Ps. (contaminated with 3 log CFU/ml of Pseudomonas aeruginosa), (3) Re. (Ps. that further supplemented with 1% v/v of Limosilactobacillus reuteri), and (4) Ext. (Ps. that further supplemented with 2 mg/mL of L. reuteri extract). After complete coagulation at 42 oC, the four batches were prepared for cold storage. Microbiological analyses investigated the total lactic acid bacteria (log CFU/g), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CFU/g), and Mold and yeast (CFU/g) for 0-15 days with 3 days interval. Results were presented in Figure 6 A and B.

Figure 6. Effect of L. reuteri (cells and extract) on microbial growth in fermented milk. The total count of LAB (including L. reuteri) was estimated on MRS agar medium, while Ps. aeruginosa counts were estimated on CN agar medium

The presented data (Figure 6A) showed general increasing in the total lactic acid populations till the end of 6th storage day. Then numbers gradually decreased to the least (6.4 log CFU/g) by the end of 15 days storage period as widely reported by many researchers.39 This decline in LAB populations is normal and can be attributed to the accumulation of lactic acid.40 Inclusion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (2.9 log CFU/ml) contributed to decrease the number of total lactic bacteria by 0.27 log CFU at the beginning of cold storage, and 0.12 log CFU after 3 days. After that, numbers sharply declined from 7.48 log CFU/mL (at the 3rd day) to 7 log CFU/mL (6th day), 6.48 log CFU/mL (9th day), 5.62 log CFU/mL (12th day), reaching to 5.58 Log CFU/mL (15th day) as predicted due to the antagonistic metabolism of Pseudomonas aeruginosa that interferes with membrane permeability of the host bacteria as introduced in Table 4 and confirmed by Bharali et al.41 Addition of L. reuteri cells contributed to LAB increasing in greater way than the control. Addition of L. reuteri extract firstly caused inhibition in the growth of lactic acid bacteria, but after 6 days enhanced the number of viable lactic acid bacteria which was greater than Ps. – treated batch by 0.23 log CFU/mL (6th day), 0.51 log CFU/mL (9th day), 1.13 log CFU/- (12th day), and 0.77 log CFU/mL (15th day).

Figure 6 B showed that the numbers of Pseudomonas aeruginosa increased from 2.9 log CFU/mL at the beginning of storage to 4.55 log CFU/mL (3rd day), 4.40 log CFU/mL (6th day), 4.90 log CFU/mL (9th day), 5.23 log CFU/mL (12th day), 5.19 log CFU/mL (15th day). After the addition of L. reuteri, numbers of Pseudomonas aeruginosa were declined from 4.55 to 2.49 log CFU/mL (3rd day), from 4.40 to 2.30 log CFU/mL (6th day), from 4.90 to 3.03 log CFU/mL (9th day), from 5.23 to 3.03 log CFU/mL (12th day), and from 5.19 to 3.11 log CFU/mL by the end of 15th day. Similar results were obtained by Tan et al.42 who concluded that some protective LAB can inhibit Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a polymicrobial mixed growth. In case of L. reuteri extract, the growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa was no longer detected by the end of 3rd storage day because of containing various compounds that cause pathogen and spoilage inhibition. Similar results were reported by Lima et al.12 All batches were confirmed as free of mold and yeast along the period of cold storage.

The findings of this study highlight the detrimental impact of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on yogurt starter cultures, ultimately compromising the quality of fermented dairy products. However, the results also demonstrate the potential of Limosilactobacillus reuteri as an effective biocontrol agent. The incorporation of viable L. reuteri cells was shown to enhance the sensitivity of P. aeruginosa to multiple antibiotic classes, while the application of L. reuteri extracts successfully eliminated P. aeruginosa populations within three days of cold storage. These promising outcomes suggest that L. reuteri could play a vital role in improving the quality and stability of dairy products by mitigating spoilage caused by P. aeruginosa.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank National Research Centre and Qassim University for technical support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This article does not contain any studies on human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

- Quintieri L, Caputo L, Brasca M, Fanelli F. Recent Advances in the Mechanisms and Regulation of QS in Dairy Spoilage by Pseudomonas spp. Foods. 2021;10(12):3088.

Crossref - Li X, Gu N, Huang TY, Zhong F, Peng G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A typical biofilm forming pathogen and an emerging but underestimated pathogen in food processing. Front Microbiol. 2023;13:1114199.

Crossref - Carrascosa C, Millan R, Jaber JR, et al. Blue pigment in fresh cheese produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Food Control. 2015;54:95-102.

Crossref - Vidal AMC, Netto AS, Vaz ACN, et al. Pseudomonas spp: contamination sources in bulk tanks of dairy farms. Pesquisa Veterinaria Brasileira. 2017;37(9):941-948.

Crossref - Ibrahim MME, Elsaied EI, Abd El Aal SF, Bayoumi MA. Prevalence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in milk and some dairy products with reduction trials by some natural preservatives. J Adv Vet Res. 2022;12(4):434-438.

- El Feghali PAR, Nawas T. Pyocyanin: a powerful inhibitor of bacterial growth and biofilm formation. Madridge J Case Rep Stud. 2018;3(1):101-107.

Crossref - Fourie R, Pohl CH. Beyond antagonism: the interaction between Candida species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Fungi. 2019;5(2):34.

Crossref - Fugere A, Seguin DL, Mitchell G, et al. Interspecific small molecule interactions between clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus from adult cystic fibrosis patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86705.

Crossref - Swati RT, Preeti T. In vitro antagonistic activity of Pseudomonas s against Rhizoctonia soloni. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2015;9(25):1622-1628.

Crossref - Millette G, Langlois JP, Brouillette E, Frost EH, Cantin AM, Malouin F. Despite antagonism in vitro, Pseudomonas aeruginosa enhances Staphylococcus aureus colonization in a murine lung infection model. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2880.

Crossref - Stanojević-Nikolić S, Dimić G, Mojović L, Pejin J, Djukić-Vuković A, Kocić-Tanackov S. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid against pathogen and spoilage microorganisms. J Food Process Preserv. 2016;40(5):990-998.

Crossref - Lima EMF, Soutelino MEM, Silva ACdO, Pinto UM, Todorov SD, Rocha RdS. Current Updates on Limosilactobacillus reuteri: Brief History, Health Benefits, Antimicrobial Properties, and Challenging Applications in Dairy Products. Dairy. 2025;6 (2):1-17.

Crossref - Al-Gamal MS, Ibrahim GA, Sharaf OM, et al. The protective potential of selected lactic acid bacteria against the most common contaminants in various types of cheese in Egypt. Heliyon. 2019;5(3):e01362.

Crossref - Baptista JP, Teixeira GM, de Jesus MLA, et al. Antifungal activity and genomic characterization of the biocontrol agent Bacillus velezensis CMRP 4489. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):17401.

Crossref - Muller M, Merrett ND. Pyocyanin production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa confers resistance to ionic silver. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(9):5492-5499.

Crossref - Andrews JM. BSAC standardized disc susceptibility testing method (version 4). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56(1):60-76.

Crossref - El-Ssayad MF, Abd-Rabou AA, El-Sayed HS. Utilization of lactobacilli extracts as antibacterial agent and to induce colorectal cancer cells apoptosis: Application in white soft cheese. Food Biosci. 2023;56:103252.

Crossref - Ramalho R, Cunha J, Teixeira P, Gibbs PA. Modified Pseudomonas agar: new differential medium for the detection/enumeration of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mineral water. J Microbiol Methods. 2002;49(1):69-74.

Crossref - Toppo SR, Tiwari P. Phosphate solubilizing rhizospheric bacterial communities of different crops of Korea district of Chattisgarh, India. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2015;9(25):1629-1636.

Crossref - Rakh RR, Dalvi SM, Raut LS, Manwar AV. Microbiological Management of Stem Rot Disease of Groundnut Caused by Sclerotium rolfsii Sacc, by Exploiting Pseudomonas aeruginosa. AL98. Res J Agril Sci. 2022;13:415-421

- Singh A, Agarwal A, Xu YJ. Novel cell-killing mechanisms of hydroxyurea and the implication toward combination therapy for the treatment of fungal infections. Antimicrob Agents and Chemother. 2017;61(11):10-128.

Crossref - Faergemann J, Hedner T, Larsson P. The in vitro activity of pentane-1, 5-diol against aerobic bacteria. A new antimicrobial agent for topical usage? Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85(3):203-205.

Crossref - El Khaldy AAS, Janen A, Abushanab A, Stallworth E. Synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activities of some dithiophosphate silane complexes. Main Group Metal Chemistry. 2016;39(5-6):167-174.

Crossref - Pereira BMP, Tagkopoulos I. Benzalkonium chlorides: uses, regulatory status, and microbial resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019;85:e319- e377.

Crossref - Amankwah FKD, Gbedema SY, Boakye YD, Bayor MT, Boamah VE. Antimicrobial potential of extract from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate. Scientifica. 2022;2022:4230397.

Crossref - Zhou J, Xue R, Liu S, et al. High di-rhamnolipid production using Pseudomonas aeruginosa KT1115, separation of mono/di-rhamnolipids, and evaluation of their properties. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2019;7:245.

Crossref - Deshmukh N, Kathwate G. Biosurfactant production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Strain LTR1 and its application. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2023;13(1):10.

Crossref - Davies BW, Kohanski MA, Simmons LA, Winkler JA, Collins JJ, Walker GC. Hydroxyurea induces hydroxyl radical-mediated cell death in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell. 2009;36(5):845-860.

Crossref - Ambrosino A, Pironti C, Dell’Annunziata F, et al. Investigation of biocidal efficacy of commercial disinfectants used in public, private and workplaces during the pandemic event of SARS-CoV-2. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):5468.

Crossref - Morita Y, Tomida J, Kawamura Y. Responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to antimicrobials. Front Microbiol. 2014;4:75337.

Crossref - Lorusso AB, Carrara JA, Barroso CDN, Tuon FF, Faoro H. Role of efflux pumps on antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(24):15779.

Crossref - De Wit JC, Rombouts FM. Antimicrobial activity of sodium lactate. Food Microbiol. 1990;7(2):113-120.

Crossref - Küçük HB, Yusufoğlu A, Mataracı E, Döşler S. Synthesis and Biological Activity of New 1, 3-Dioxolanes as Potential Antibacterial and Antifungal Compounds. Molecules. 2011;16(8):6806-6815.

Crossref - Sakko M, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Sakko S, Richardson M, Sorsa T. Antibacterial activity of 2-hydroxyisocaproic acid (HICA) against obligate anaerobic bacterial species associated with periodontal disease. Microbiol Insights. 2021;14:11786361211050086.

Crossref - Koistinen VM, Hedberg M, Shi L, et al. Metabolite Pattern Derived from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum—Fermented Rye Foods and In Vitro Gut Fermentation Synergistically Inhibits Bacterial Growth. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2022;66(21):2101096.

Crossref - Potera C. Making succinate more successful. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(12):A832–A835.

Crossref - Mu W, Yu S, Zhu L, Zhang T, Jiang B. Recent research on 3-phenyllactic acid, a broad-spectrum antimicrobial compound. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;95(5):1155-1163.

Crossref - Yehye WA, Rahman NA, Saad O, et al. Rational design and synthesis of new, high efficiency, multipotent Schiff base-1, 2, 4-triazole antioxidants bearing butylated hydroxytoluene moieties. Molecules. 2016;21(7):847.

Crossref - Ziarno M, Zareba D, Scibisz I, Kozlowska M. Comprehensive studies on the stability of yogurt-type fermented soy beverages during refrigerated storage using dairy starter cultures. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1230025.

Crossref - Mani-Lopez E, Palou E, Lopez-Malo A. Probiotic viability and storage stability of yogurts and fermented milks prepared with several mixtures of lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97(5):2578-2590.

Crossref - Bharali P, Saikia JP, Ray A, Konwar BK. Rhamnolipid (RL) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa OBP1: a novel chemotaxis and antibacterial agent. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces. 2013;103:502-509.

Crossref - Tan CAZ, Lam LN, Biukovic G, et al. Enterococcus faecalis antagonizes Pseudomonas aeruginosa growth in mixed-species interactions. J Bacteriol. 2022;204(7):e00615-21.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.