ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Antibiotic use in poultry production to treat infections caused by bacteria has led to antibiotic resistance. Many countries have resorted to banning antibiotics in livestock rearing. Probiotics can be used as an alternative to antibiotics as they have the potential to boost bird health and aid in the production of safe consumable produce. The study aimed to isolate Bacillus spp. from samples collected from the vegetable garden, sewage works site, maize milling site, and chicken coop soil. Four isolates were subjected to probiotic screening test. One isolate was further characterized according to 16S gene sequencing. The tested Bacillus spp. indicated resistance to low pH, gastric juice, bile salts and negative test to haemolysis. The isolates exhibited broad spectrum antimicrobial potency against E. coli, Salmonella Typhi, and Staphylococcus aureus. Three Bacillus spp. were resistant to at least one tested antibiotic, while Bacillus PW3 was susceptible to all antibiotics. Further characterization of one Bacillus isolate was done by PCR amplification and sequencing of the 16S rDNA gene. The results confirmed this isolate as Bacillus-related spp. and closely related to Bacillus velezensis. Bacillus PW1 and Bacillus GM3 exhibited potential probiotic characteristics and potential for use in poultry production.

Bacillus spp., Probiotics, Antimicrobial Resistance, 16S rDNA, Antibacterial Activity

Poultry production is one of the thriving industries that offers high-quality protein to improve dietary needs of continuously growing population, therefore there is transitioning from subsistence farming to intensive production. In 2017, global egg production reached 87 million tonnes and poultry meat production reached 123 million tonnes, as reported by Laca et al.1 The production is expected to grow in order to satisfy the growing population of people. One of the major challenges in poultry production is the outbreak of infections caused by microorganisms such as Staphylococcus aureus. As a result, antibiotics have been continuously and improperly used as a preventative measure to keep the animals/birds free from these infections. On the other hand, it is known that extensive application of antimicrobials lead to antimicrobial resistance2 and also affect the natural beneficial bacteria.

Antibiotic-resistant pathogens result in ineffective treatment, economic losses and plays a role in dissemination of resistant bacteria and genes posing a risk to human health.3 Previous studies have demonstrated the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Enterococcus spp. and Staphylococcus spp. in aquaculture ponds.2 Meat from poultry is a common source of evolving antibiotic resistance bacteria. Transmission of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to humans occurs through direct ingestion of poultry meat or products. Because of these challenges associated with overuse of antibiotics, there is a call to ban antibiotics use in poultry production.

Probiotics are live microorganisms that provide health benefits to the host by inhibiting the growth of infectious microbes,4 and they can be used as an alternative to antibiotics in poultry systems. The mode of action of probiotics include competing with pathogens for receptor binding sites in the intestinal tract, production of metabolites with antimicrobial capabilities, and stimulation of the immune system.5,6 Probiotics are inherently competitive and they try to eradicate other bacteria that might harm the digestive system. The microbial population diversity is shaped by competition among different microorganisms for the nutrients in the digestive system.7 Probiotics can serve as immune boosters, preserve intestinal integrity to increase endogenous digestive enzyme activities, and a sustenance of the intestinal microflora ecosystem to inhibit pathogen proliferation.8

Probiotics have to overcome unpredictable factors like bile acids, gastric juice, and competition from other microorganisms. One of the most significant acid tolerance mechanisms in Bacillus spp. is the proton motive force dependent proton efflux pump, which works to preserve pH homeostasis.9 Large intestines harbours diverse microorganisms and metabolic activity.10 Low pH is a barrier to survival of microorganisms in the intestines of poultry.11 In order to survive in such low pH, probiotics must be combined with other food products therefore enabling them to survive in the gastro intestinal tract (GIT). Probiotic bacteria must endure harsh conditions of the small intestines so that they provide desired health benefits to poultry.

Studies have been done by scientists to identify and characterize bacteria with potential of being probiotics from environmental samples.12,13 The genus Bacillus have the ability to produce antimicrobial substances and spores that confer the ability to thrive in different habitats.14 This makes Bacillus spp. attractive to be exploited as probiotics in humans and animals. Different Bacillus spp. are being used as presumed probiotics.15,16

Microorganisms

Analysis of all samples was done at the NUST Microbiology and Biotechnology labs. Four bacterial isolates were isolated from soil and identified as Bacillus spp. according to morphological and biochemical tests. Biochemical tests done included motility, catalase, citrate, indole, gram reaction and spore formation tests. Hemolysis and antimicrobial susceptibility tests were done as safety evaluation tests. PCR and 16S rRNA sequencing were done on one representative isolate for confirmation. The isolate was stored in glycerol stock at 5 °C for long-term preservation and use. For probiotic characterization, bacteria were assessed for their ability to survive in conditions similar to GIT (bile salt, pH 2, pH 4 and gastric juice) using the following methods.

Viability of Bacillus spp. in synthetic media same as GIT conditions

Viability of Bacillus isolates was determined under culture conditions comparable to GIT of chicken stomach. Bacillus cultures were added to three test tubes containing 10 ml each of freshly made lysogeny broth having conditions similar to the GIT. Samples were collected at (Time = 0 hours) and after the desired time (Time≠) for each condition being tested, then cultured on nutrient agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. Viable cells were counted. The formula described by Burgain17 was used to determine the bacteria’s viability.

Viability = HT1 / HT0 x 100,

whereby HT1 = log CFU after changing to the required medium at time ≠ 0 h and HT0 = log CFU at time = 0 h

pH resistance

The prepared Bacillus cultures were inoculated into flasks with 10 ml nutrient broths at pH 2 and pH 4 respectively.18 Samples were collected at time 0 hours and after incubation for 4 hours at 37 °C. Colony count was done after 0.1 ml aliquot of each sample was cultured on nutrient agar plates at 37 °C for 24 hours. Viability of Bacillus spp. was calculated using formula above.

Bile salts resistance

An aliquot of each Bacillus culture was grown in 10 mL of freshly made lysogeny broth, which contained 0.3 grams of bile agar in 100 ml of distilled water, then incubated at 37 °C for 3 hours in a shaker incubator at 150 rpm. Samples were collected at time = 0 hours and time = 3 hours then spread in nutrient agar plates and incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C. Using the previously mentioned formula, the viability of bacteria was determined.

Gastric juice tolerance

10 ml of gastric juice, which contained (0.1 grams of NaCl, 7 mL of 0.2 M HCl, 60 ml of distilled water 0.2 grams of pepsin, and adjusted to pH 2.) was suspended with each bacterial culture that had been cultured overnight in lysogeny broth. For two hours, the suspension was stirred at 150 rpm and incubated at 37 °C. Samples were collected before the incubation period at time = 0 hours and after the incubation period at time = 2 hours.18 An aliquot of each suspension was spread on nutrient agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. Bacterial colonies were counted. Viability was determined using the same formula as previously mentioned.

Data analysis

A two-way analysis of variance (at α = 0.001, 0.01, 0.05 and 0.1) and Tukey’s HSD Test based on Pairwise comparisons of mean were performed to assess the viability of Bacillus spp. in conditions same as GIT using R software. Results were presented in percentages of the mean ± standard deviation of replicates.

Antimicrobial activity

Antimicrobial activity was done against 3 poultry pathogens which were E. coli, Salmonella typhi and Staphylococcus aureus using disk diffusion assay method. Bacillus isolates were cultivated in flasks containing 100 ml of lysogeny broth each, incubated at 37 °C in a shaking incubator running at 150 rpm for 72 hours followed by centrifugation and then filtered with standard membrane according to the recommendations of Al-Turk et al.19 Acetone was added to the flasks at a ratio of 4:1 to concentrate the isolates’ metabolites, and the flasks were put in a shaker incubator for 2 hours at 100 rpm. Acetone was evaporated at 45 °C to concentrate the organic phase, and the resulting extracts were kept at 4 °C until needed. Autoclaved paper disks were impregnated with the resulting extracts. The disks were placed on agar plates inoculated with test pathogens (Salmonella typhi, E. coli, and Staphylococcus aureus). The agar plates were incubated for 48 hours at 37 °C. As control, 5 µg/mL of the antibiotics methicillin and kanamycin were utilized. Calipers were used to estimate the affected zone’s diameter in millimetres.

Molecular identification

Further identification of Bacillus isolates was achieved by bacterial DNA extraction using boiling method followed by the PCR amplification method. For PCR amplification, two microliters of each of the DNA samples was mixed with a master mix having a total volume of 23 µl. The master mix had the following: 12.5 µl of Dream Taq green PCR Master Mix, 0.5 µl each of forward and reverse primer, and 2 µl of Magnesium chloride. The initial DNA denaturation step was at 95 °C for 2 minutes. This was followed by 25 cycles of sequence amplification steps, denaturation at 95 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 60 °C for 30 seconds, extension at 72 °C for 1 minute 30 seconds, and a final elongation step at 72 °C for 10 mins. Primers used were rD1 and fD1. Only one isolate was further identified according to 16S rDNA gene sequencing. The amplified PCR products were sent to Inqaba Biotec Company in South Africa for purification and Sanger sequencing.

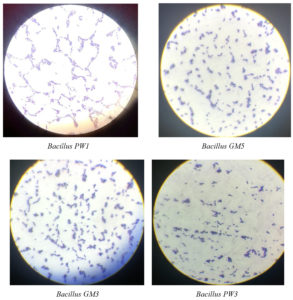

Results revealed four Bacillus spp. isolated from soil which were creamy in colour and mucoid. Characterization was done using microscopy and biochemical tests (Table 1). All the Bacillus isolates were rod-shaped Gram-positive bacteria (Figure 1). These bacterial isolates were identified and named as Bacillus PW1, Bacillus GM3, Bacillus GM5, and Bacillus PW3.

Table (1):

Biochemical tests

Parameters |

GM5 |

GM3 |

PW1 |

PW3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Spore formation |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Catalase |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Citrate |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

Hemolysis |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Motility |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Gram staining |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Assessment of viability of Bacillus spp. in synthetic media same as GIT environment

Bacillus PW1 survived the most at pH 4 with a viability of (87 ± 4%). Bacillus GM3 showed viability of (77 ± 6%) at pH 4 and (58 ± 4%) at pH 2. Bacillus GM5 survived the most at pH 4 (63 ± 4%) compared to pH 2 (36 ± 7%). Bacillus PW3 showed (65 ± 20%) survival in gastric juice and (46 ± 10%) survival in bile salt. Bacillus PW1 was the most acid-tolerant compared to other Bacillus spp., followed by Bacillus GM3 and Bacillus PW3, respectively. Bacillus GM5 was the least tolerant (Table 2). Bacillus PW1 was the most viable bacterium, showing enhanced resistance to acidic environments and hence, the highest potential for probiotic usage among other Bacillus spp. (Table 2).

Table (2):

Viability of Bacillus spp. in synthetic media same as GIT (%)

Synthetic media similar to gastro intestinal tract |

Bacillus PW1 |

Bacillus GM3 |

Bacillus GM5 |

Bacillus PW3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Gastric juice |

78 ± 1 |

61 ± 3 |

49 ± 3 |

65 ± 20 |

Bile salt |

79 ± 5 |

62 ± 6 |

57 ± 2 |

46 ± 10 |

pH 2 |

85 ± 3 |

58 ± 4 |

36 ± 7 |

56 ± 4 |

pH 4 |

87 ± 4 |

77 ± 6 |

63 ± 4 |

64 ± 8 |

Analysis of variance revealed a marginally significant effect of synthetic media conditions (bile salt, pH 2, pH 4 and gastric juice) on survival rates with a p-value of 0.0564 suggesting a trend towards changes in viability when synthetic media conditions are altered (Table 3). Bacillus spp. showed a statistical significance on tolerance and viability in synthetic media conditions with a p-value of 0.0000906 denoting a marginal effect.

Table (3):

Analysis of variance results

Source of variation |

Degrees of Freedom |

Sum of Squares |

Mean of Squares |

F-value |

p-value |

Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Synthetic media condition |

3 |

927 |

309.0 |

3.099 |

0.056 |

* |

Bacillus spp. |

3 |

4241 |

1413.7 |

14.176 |

less than 0.001 |

*** |

Synthetic media: Bacillus spp. |

9 |

935 |

103.9 |

1.042 |

0.451 |

|

Residuals |

16 |

1595 |

99.7 |

|||

Total |

31 |

7698 |

248.3 |

Sig. = significance codes: ***:0.01, **:0.05, *:0.1

According to Tukey’s HSD Test, Bacillus PW1 showed a statistical significance when compared with Bacillus GM3 at pH 2 with p-value of 0.046 at alpha 0.05 (Table 4). Overall, the tests in all synthetic media conditions did not reveal significant differences in viability among Bacillus spp. However, a notable exception was observed in bile salt tolerance when comparing Bacillus PW1 and Bacillus PW3, which approached significance (p = 0.068) at alpha 0.05.

Table (4):

Tukey’s HSD Test based pairwise comparison of Bacillus spp. across different synthetic media similar to gastrointestinal tract conditions

Synthetic media conditions |

Comparison of Bacillus spp. |

Difference |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

pH 2 |

PW1-GM3 |

27.5 ± 26.73 |

0.046 |

pH 2 |

GM5-GM3 |

-21.5 ± 26.73 |

0.097 |

pH 2 |

PW3-GM3 |

-1.5 ± 26.73 |

0.995 |

pH 2 |

PW1-GM5 |

49 ± 26.73 |

0.006 |

pH 2 |

PW3-GM5 |

20 ± 26.73 |

0.119 |

pH 2 |

PW3-PW1 |

-29 ± 26.73 |

0.038 |

Gastric juice |

GM5-GM3 |

-12 ± 59.01 |

0.840 |

Gastric juice |

PW1-GM3 |

16.5 ± 59.01 |

0.689 |

Gastric juice |

PW3-GM3 |

4 ± 59.01 |

0.992 |

Gastric juice |

PW1-GM5 |

28.5 ± 59.01 |

0.333 |

Gastric juice |

PW3-GM5 |

16 ± 59.01 |

0.707 |

Gastric juice |

PW3-PW1 |

-12.5 ± 59.01 |

0.824 |

Bile-salt |

GM5-GM3 |

-4.5 ± 36.33 |

0.954 |

Bile-salt |

PW1-GM3 |

17.5 ± 36.33 |

0.334 |

Bile-salt |

PW3-GM3 |

-15.5 ± 36.33 |

0.413 |

Bile-salt |

PW1-GM5 |

22 ± 36.33 |

0.205 |

Bile-salt |

PW3-GM5 |

-11 ± 36.33 |

0.642 |

Bile-salt |

PW3-PW1 |

-33 ± 36.33 |

0.068 |

pH 4 |

GM5-GM3 |

-14 ± 33.09 |

0.419 |

pH 4 |

PW1-GM3 |

10 ± 33.09 |

0.643 |

pH 4 |

PW3-GM3 |

-13 ± 33.09 |

0.469 |

pH 4 |

PW1-GM5 |

24 ± 33.09 |

0.130 |

pH 4 |

PW3-GM5 |

1 ± 33.09 |

0.999 |

pH 4 |

PW3-PW1 |

-23 ± 33.09 |

0.145 |

Antibacterial activity

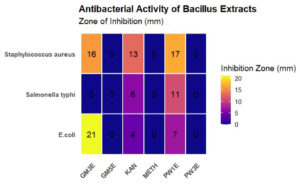

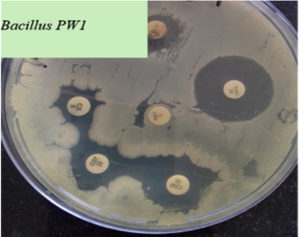

Bacillus PW1 showed broadest antimicrobial spectrum against all 3 pathogens. Bacillus GM3 was able to inhibit growth of two pathogens namely E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus; however, Salmonella Typhi was resistant to the cell free extract produced by Bacillus GM3.

Bacillus GM5 and Bacillus PW3 did not inhibit all three indicator pathogens. Of all the Bacillus spp., Bacillus GM3 exhibited largest inhibition diameter (21 mm) against E. coli (Figure 2). Two antibiotics were used as control, methicillin (METH) was used as a negative control and kanamycin (KAN) as a positive control. All three pathogens were resistant to methicillin and susceptible to kanamycin. Regarding antibiotic susceptibility, the results of our study showed that all tested Bacillus spp. were susceptible to almost all antibiotics (5 µg/mL) except methicillin for which they were all resistant. Bacillus PW1 and Bacillus GM5 were the most sensitive to cefixime and kanamycin antibiotics (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Antibacterial activity (mm) of Bacillus spp. against Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli and Salmonella typhi. PW1E Bacillus PW1 cell-free extract, PW3E Bacillus PW3 cell-free extract, GM5E = Bacillus GM5 cell-free extract, GM3E = Bacillus GM3E cell-free extract, KAN kanamycin antibiotic, METH = methicillin antibiotic

Genotypic analysis of selected Bacillus spp. using 16S rDNA gene

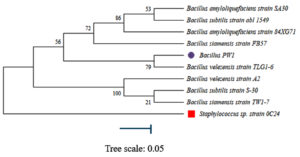

After PCR amplification and sequencing of Bacillus PW1, a consensus sequence of 858 base pairs was obtained which was aligned in the nucleotide sequence database of NCBI using BLAST search tool to estimate the sequence homology and identification of bacterial isolate by comparing consensus sequence with sequences of NCBI database. The comparison of the generated sequence with sequences of the GenBank database indicated that Bacillus PW1 belonged to the genera Bacillus (Figure 4). The sequence has been submitted to the GenBank database and obtained an accession number PX457090.

Figure 4. BLAST search showing percentage identity between the query sequence and the most similar sequences found in Sequence data base

According to the phylogenetic tree, Bacillus PW1 is closely related to Bacillus velezensis strain TLG1-6. Neighbor-joining method was used to build a phylogenetic tree using the Mega 11 software.20 Boot-strap analysis, derived from 1000 sampling, was used to determine confidence values of individual branches in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 5). The evolutionary history of the analyzed data is represented by the bootstrap consensus tree, which was generated from 1000 replicates. The Maximum Composite Likelihood method was used to determine sequence distances.20 This analysis involved 10 nucleotide sequences. The amount of change estimated to have occurred between a pair of nodes was represented by branches. Staphylococcus sp. strain was the outgroup.

Research has proven that probiotics play an important role in keeping bird intestinal morphology,21 suppressing the growth of harmful bacteria,4 and enhancing the digestion and absorption of nutrients. As a result, they contribute to the overall growth and development of livestock.

Results in our study showed that all four Bacillus spp. obtained were motile (Table 1), which according to Cousin et al.22 provides competitive advantages in terms of nutrient acquisition, niche colonization, and triggering of the innate immune system. Motile probiotics have an increased ability to navigate through the GIT, allowing them to reach and colonize various regions of the gut more effectively. Motility also enhances the probiotic’s capacity to move through the mucus layer and adhere to the intestinal epithelium, improving their chances of establishing a stable presence in the gut. Interestingly, spores of Bacillus spp. are currently used as probiotics and competitive exclusion agents in both human and animal consumption.23 Similarly, in our study all four Bacillus spp. were found to be spore formers. Bacteria that form spores have been observed to complete the sporulation and germination cycle in the GIT of guinea pigs.24

Among the secondary metabolites of Bacillus spp., subtilisin and subtilosin are primarily known for aiding digestion and reducing allergenicity. A study done by Ostrowski et al.25 reported that bacitracin produced by certain Bacillus spp. inhibits E. coli and S. aureus. The antagonistic activities of Bacillus spp. are crucial in preventing the infection or invasion of pathogenic bacteria. In our study, Bacillus PW1 showed antagonistic effect against E. coli, Salmonella Typhi and Staphylococcus aureus. These results are similar to findings of Chaiyawan et al.26 Studies done by Afroj et al.27 highlight the inhibitory effect of Bacillus velezensis AP 183 strain against Staphylococcus aureus, further confirming our findings.

In our study, we found that Bacillus GM3, Bacillus PW3, and Bacillus GM5 did not inhibit the growth of Salmonella Typhi. These results align with previous research done by Barbosa et al.28 that showed that certain strains of Bacillus spp. isolated from the GIT of broiler chickens did not have inhibitory activity against Salmonella spp. However, we observed that Bacillus GM3 did exhibit inhibitory effects against E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Interestingly, studies by Nithya & Halami29 reported the antimicrobial activity of Bacillus spp. against Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella boydii and Salmonella Typhi. Our results are consistent with findings of Kan et al.30 demonstrating antagonism against E. coli and Salmonella Typhi. Interestingly, Bacillus PW3 and Bacillus GM5 did not have any inhibitory effect against Salmonella Typhi, E. coli, and Staphylococcus aureus. This is because genus Bacillus is a group of bacteria that includes both inhibitory and non-inhibitory compound-producing bacteria.

In order for probiotics to exert their expected benefits in the intestines, they must remain viable during ingestion and in the challenging environments of GIT, including the acidic conditions of the stomach. The survival of Bacillus spp. in the gastric juice is depended on the ability to resist low pH, which is an important attribute for probiotics.31 In our study, the effect of low pH was seen after the studied Bacillus spp. were exposed to low pH (pH 2.0 and pH 4.0) for 3 hours. Bacillus PW1 had the highest viability at pH 2 and greater tolerance at pH 4 compared to other Bacillus spp. Bacillus PW3 and Bacillus GM5 demonstrated over 35% pH tolerance at pH 2. In a study by Lee et al.,32 three Bacillus strains showed relative pH tolerances of 93%, 91% and 95% after exposure to low pH. These values are higher than the values obtained in our study. Among the Bacillus spp. tested, Bacillus PW1 exhibited extremely high tolerance to acid, gastric juice, and bile salt, indicating its better adaptation to the target host. This bacteria was isolated from poultry waste in a poultry farm, which corresponds to the findings of Pan & Yu,33 who isolated Bacillus spp. that survived low pH values from the poultry environment.

In gastric juice, the survival rates of all Bacillus spp. ranged from 61%-78% after 3 hours of exposure. These values are slightly lower than those reported by Lee et al.32 One of the main reasons for the resistance of Bacillus spp. to gastric juice is that Bacillus spp. tend to form spores. These spores are highly resistant to environmental stresses, such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and acidic conditions. When the bacterium detects unfavourable conditions, it enters a dormant state, enabling it to survive until more favourable conditions occur. Interestingly, Bacillus PW3, Bacillus GM3 and Bacillus PW1 showed tolerance to 0.3% ox gal bile, while Bacillus GM5 exhibited weak tolerance. This suggests that all of these cultures belong to the “tolerant” group. The reason for this observed resistance of bacteria to the antimicrobial properties of bile salts is attributed to the production of bile hydrolase enzymes, that protect bacteria against the toxic effects of bile. Bile salt hydrolases are generally intracellular, oxygen-insensitive enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of bile salts.34 The analysis of variance indicated that survival rates and tolerance of different synthetic media conditions is mainly explained by bacteria type. Bacillus PW1 generally was the most tolerant and had the highest survival rate, whilst Bacillus GM3 exhibited moderate survival rates.

Generally, all Bacillus isolates in this study were susceptible to most of the tested antibiotics, which means they can be safely used as probiotics without transmitting drug resistance genes to other pathogens in the gastrointestinal tract. The ability of probiotics to be susceptible to antibiotics is also a critical measure for selecting them as probiotics.35 Three of tested Bacillus isolates including Bacillus PW1 showed resistance to methicillin (Figure 3). The resistance of Bacillus PW1 to methicillin antibiotic is due to the use of antibiotics in poultry farming, contributing to evolution of resistant bacterial populations. These bacteria acquire resistance genes through horizontal gene transfer or mutations.

Out of all Bacillus spp. in this study, only Bacillus PW1 was chosen for further characterization based on primary selection criteria, which included antimicrobial activity against test pathogens, ability to survive under harsh conditions of GIT and susceptibility to antibiotics. All the tested isolates did not demonstrate α-haemolytic or -haemolytic activity when cultured on blood agar plates. It is worth noting that assessing haemolytic activity is highly recommended by the European Food Safety Authority for bacteria targeted for use in food products, irrespective of their Generally Regarded as safe status.

In this study, phylogenetic analysis was done on the molecular data obtained for Bacillus PW1. This was used to classify and understand the relationships between closely related species. Bacteria can be identified to species level by targeting 16S rDNA gene which makes studying bacterial phylogeny and taxonomy possible.36 This gene, which have both conserved and variable regions, with the conserved regions reflecting phylogenetic relationships and serving as sites for PCR priming was used in our study. According to the phylogenetic tree constructed (Figure 5), Bacillus PW1 was closely related to Bacillus velezensis.

Based on the 16S gene sequencing we confirmed PW1 isolate as Bacillus velezensis strain. This isolate showed strong probiotic properties, compared to other Bacillus spp. tested in this study. It exhibited better antibiotic susceptibility, broader antimicrobial activity, and a greater ability to survive under conditions similar to the chicken GIT Therefore, it exhibits a great potential to be used as probiotic in poultry farming.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the National University of Science and Technology for facilitating the conduct of this article and providing laboratory equipment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

This study was funded by the National University of Science and Technology Research group vide funding grant number RDB/11/25.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Laca A, Laca A, Diaz M. Environmental impact of poultry farming and egg production. In: Galanakis CM (eds). Environmental Impact of Agro-Food Industry and Food Consumption. Academic Press. 2021:81- 100.

Crossref - Apata DF. Antibiotic Resistance in Poultry. International J Poultry Sci. 2009;8(4):404-408.

Crossref - Nhung NT, Chansiripornchai N, Carrique-Mas JJ. Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacterial Poultry Pathogens: A Review. Front Vet Sci. 2017;4:126.

Crossref - Salminen S, Nybom S, Meriluoto J, Collado MC, Vesterlund S, El-Nezami H. Interaction of probiotics and pathogens-benefits to human health? Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2010;21(2):157-167.

Crossref - Madsen KL. Enhancement of Epithelial Barrier Function by Probiotics. J Epithel Biol Pharmacol. 2012;5(1):55-59.

Crossref - Shenderov BA. Probiotic (symbiotic) bacterial languages. Anaerobe. 2011;17(6):490-495.

Crossref - Coyte KZ, Rakoff-Nahoum S. Understanding Competition and Cooperation within the Mammalian Gut Microbiome. Curr Biol. 2019;29(11):R538-R544.

Crossref - Yang J, Qian K, Wang C, Wu Y. Roles of Probiotic Lactobacilli Inclusion in Helping Piglets Establish Healthy Intestinal Inter-environment for Pathogen Defense. Probiotics Antimicrob Prot. 2018;10(2):243-250.

Crossref - Jain PK, Jain V, Singh AK, Chauhan A, Sinha S. Evaluation on the responses of succinate dehydrogenase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, malate dehydrogenase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase to acid shock generated acid tolerance in Escherichia coli. Adv Biomed Res. 2013;2(1):75.

Crossref - Rajilic-Stojanovic M, Heilig HGHJ, Tims S, Zoetendal EG, De Vos WM. Long term monitoring of the human intestinal microbiota composition. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15(4):1146-1159.

Crossref - Berthold-Pluta A, Pluta A, Garbowska M. The effect of selected factors on the survival of Bacillus cereus in the human gastrointestinal tract. Microb Pathogenesis. 2015;82:7-14.

Crossref - Duc LH, Hong HA, Barbosa TM, Henriques AO, Cutting SM. Characterization of Bacillus Probiotics Available for Human Use. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(4):2161-2171.

Crossref - Mohammad SM, Mahmud-Ab-Rashid NK, Zawawi N. Probiotic properties of bacteria isolated from bee bread of stingless bee Heterotrigona itama. J Apic Res. 2021;60(1):172-187.

Crossref - Abriouel H, Franz CMAP, Omar NB, Galvez A. Diversity and applications of Bacillus bacteriocins. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;35(1):201-232.

Crossref - Rengpipat S, Rukpratanporn S, Piyatiratitivorakul S, Menasaveta P. Immunity enhancement in black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) by a probiont bacterium (Bacillus S11). Aquaculture. 2000;191(4):271-288.

Crossref - McIntosh D, Samocha TM, Jones ER, Lawrence AL, McKee DA, Horowitz S, Horowitz A. The effect of a commercial bacterial supplement on the high-density culturing of Litopenaeus vannamei with a low-protein diet in an outdoor tank system and no water exchange. Aquacultural Engineering. 2000;21(3):215-227.

Crossref - Burgain J. Microencapsulation de bacteries probiotiques dans des matrices laitieres: Etude des mecanismes de formation par une approche multi-echelle. Procedes Biotechnologiques et Alimentaires, Universite de Lorraine, Vandoeuvre-les-Nancy. Published online 2013.

- Unban K, Kodchasee P, Shetty K, Khanongnuch C. Tannin-tolerant and Extracellular Tannase Producing Bacillus Isolated from Traditional Fermented Tea Leaves and Their Probiotic Functional Properties. Foods. 2020;9(4):490.

Crossref - Al-Turk A, Odat N, Massadeh MI. Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Antibiotic Producing Bacillus licheniformis Strains Isolated from Soil. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2020;14(4):2363-2370.

Crossref - Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(30):11030-11035.

Crossref - Ogbuewu IP, Mabelebele M, Sebola NA, Mbajiorgu C. Bacillus Probiotics as Alternatives to In-feed Antibiotics and Its Influence on Growth, Serum Chemistry, Antioxidant Status, Intestinal Histomorphology, and Lesion Scores in Disease-Challenged Broiler Chickens. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:876725.

Crossref - Cousin FJ, Lynch SM, Harris HMB, et al. Detection and Genomic Characterization of Motility in Lactobacillus curvatus: Confirmation of Motility in a Species outside the Lactobacillus salivarius Clade. Elkins CA, ed. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(4):1297-1308.

Crossref - Mazza P. The use of Bacillus subtilis as an antidiarrhoeal microorganism. Boll Chim Farm. 1994;133(1):3-18.

- Angert ER, Losick RM. Propagation by sporulation in the guinea pig symbiont Metabacterium polyspora. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(17):10218-10223.

Crossref - Ostrowski A, Mehert A, Prescott A, Kiley TB, Stanley-Wall NR. YuaB Functions Synergistically with the Exopolysaccharide and TasA Amyloid Fibers To Allow Biofilm Formation by Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(18):4821-4831.

Crossref - Chaiyawan N, Taveeteptaikul P, Wannissorn B, et al. Characterization and Probiotic Properties of Bacillus Strains Isolated from Broiler. Thai J Vet Med. 2010;40(2):207-214.

Crossref - Afroj S, Brannen AD, Nasrin S, et al. Bacillus velezensis AP183 Inhibits Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Formation and Proliferation in Murine and Bovine Disease Models. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:746410.

Crossref - Barbosa TM, Serra CR, La Ragione RM, Woodward MJ, Henriques AO. Screening for Bacillus Isolates in the Broiler Gastrointestinal Tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(2):968-978.

Crossref - Nithya V, Halami PM. Evaluation of the probiotic characteristics of Bacillus species isolated from different food sources. Ann Microbiol. 2013;63(1):129-137.

Crossref - Kan L, Guo F, Liu Y, Pham VH, Guo Y, Wang Z. Probiotics Bacillus licheniformis Improves Intestinal Health of Subclinical Necrotic Enteritis-Challenged Broilers. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:623739.

Crossref - Kavitha M, Raja M, Perumal P. Evaluation of probiotic potential of Bacillus spp. isolated from the digestive tract of freshwater fish Labeo calbasu (Hamilton, 1822). Aquaculture Reports. 2018;11:59-69.

Crossref - Lee S, Lee J, Jin YI, et al. Probiotic characteristics of Bacillus strains isolated from Korean traditional soy sauce. LWT – Food Sci Technol. 2017;79:518-524.

Crossref - Pan D, Yu Z. Intestinal microbiome of poultry and its interaction with host and diet. Gut Microbes. 2014;5(1):108-119.

Crossref - Liong MT, Shah NP. Bile salt deconjugation ability, bile salt hydrolase activity and cholesterol co-precipitation ability of Lactobacilli strains. Int Dairy J. 2005;15(4):391-398.

Crossref - Hummel AS, Hertel C, Holzapfel WH, Franz CMAP. Antibiotic Resistances of Starter and Probiotic Strains of Lactic Acid Bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(3):730-739.

Crossref - Janda JM, Abbott SL. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing for Bacterial Identification in the Diagnostic Laboratory: Pluses, Perils, and Pitfalls. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(9):2761-2764.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.