ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Biofilm formation is a major virulence factor in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), contributing to chronic infections and antibiotic resistance. The intercellular adhesion icaA and icaB genes are key determinants involved in biofilm synthesis and stabilization. Understanding the prevalence and correlation of these genes with biofilm formation is essential for improved diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of icaA and icaB genes and their correlation with phenotypic biofilm formation in MRSA isolates from clinical samples. An observational study was conducted over two years in a tertiary care hospital in India. A total of 102 MRSA isolates were phenotypically assessed for biofilm formation using the tissue culture plate method. Genotypic detection of icaA and icaB was performed by real-time PCR. Statistical correlation between gene presence and biofilm formation was analyzed using the chi-square test. Among the 102 MRSA isolates, 36.3% were biofilm producers, including 15.7% strong, 11.8% moderate, and 8.8% weak producers. Genotypic analysis showed that 66.7% of isolates harbored both icaA and icaB, while 20% carried only icaB. A strong correlation was observed between icaA presence and strong biofilm production (p < 0.05), whereas icaB alone did not correlate significantly with biofilm formation. The findings highlight the critical role of icaA in initiating biofilm formation, while icaB may contribute to biofilm stabilization. Comprehensive phenotypic and genotypic screening is essential for understanding MRSA pathogenicity and improving infection control strategies.

MRSA, Biofilm, icaA, icaB, Real-time PCR, Antibiotic Resistance

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has emerged as a major global health threat, primarily due to its resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics and its ability to cause a spectrum of infections, ranging from minor skin and soft tissue infections to life-threatening conditions such as pneumonia, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and septicemia.1,2 The burden of MRSA is particularly concerning in healthcare settings, where it is a leading cause of hospital-acquired (nosocomial) infections and is associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs.3,4 A key factor contributing to the persistence and pathogenicity of MRSA is its ability to form biofilms, which are complex microbial communities adhered to surfaces and embedded in a self-produced extracellular matrix.5 These biofilms can develop on both biotic surfaces (such as tissues) and abiotic surfaces (like catheters, prosthetics, and implants), thereby complicating clinical management.6 Biofilm formation not only enhances bacterial survival under hostile conditions but also significantly increases resistance to antibiotics and evasion from host immune responses.7,8

Central to the biofilm-forming capacity of MRSA is the intercellular adhesion (ica) operon, particularly the icaA and icaB genes. The icaA gene encodes N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, which catalyzes the synthesis of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA), a key component of the biofilm matrix.9,10 The icaB gene, in turn, encodes a deacetylase that modifies the PIA structure, enhancing its adhesive and structural properties, thereby contributing to the robustness and maturity of biofilms.11

Recent studies have extended this focus to the entire icaADBC operon, showing a high prevalence of icaA, icaB, icaC, and icaD among multidrug-resistant S. aureus isolates, particularly those with strong biofilm-forming ability.12 Moreover, investigations in both clinical and environmental isolates indicate that biofilm gene carriage varies geographically and may be influenced by selective antibiotic pressure.13 Additionally, regulatory networks such as the agr quorum-sensing system and global regulators like sarA and sigB have been shown to interact with the ica operon, suggesting that biofilm formation in MRSA may result from both ica-dependent and ica-independent mechanisms.14

The expression and prevalence of these genes have been directly linked to the strength and density of biofilm formation, making them important molecular markers for understanding biofilm-associated infections. Investigating the presence and functional role of icaA and icaB genes in MRSA isolates can therefore provide critical insights into biofilm-associated pathogenesis and guide the development of targeted anti-biofilm therapies. In this context, the present study seeks to evaluate the prevalence of icaA and icaB genes in MRSA isolates from clinical samples and explore their correlation with biofilm formation capacity, thereby contributing to the increasing evidence on biofilm-related virulence mechanisms in MRSA and supporting efforts for better infection control and treatment strategies.

This observational study was conducted over a period of two years (January 2023 to December 2024) in the Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SGT University, Gurugram, India. The protocol of the study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SGT University (IEC/FMHS/MD/MS/2023-27).

A total of 127 non-duplicate Staphylococcus aureus isolates were recovered from various clinical specimens, including pus, blood, Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), and high vaginal swabs, received in the microbiology laboratory. Identification of S. aureus was performed based on colony morphology, Gram staining, catalase, and coagulase tests. Methicillin resistance was determined using the cefoxitin disc diffusion method (30 μg) as per the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines. Out of the total isolates, 102 were confirmed as MRSA and included for further analysis.15

Phenotypic detection of biofilm formation

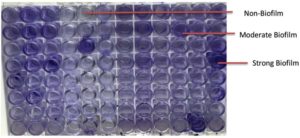

Biofilm production was assessed by the tissue culture plate (TCP) method. MRSA isolates were cultured in BHI broth supplemented with 2% sucrose and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Cultures were diluted 1:100 and inoculated into 96-well microtiter plates. After incubation, wells were washed with PBS, stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and OD was measured at 450 nm.16 Biofilm formation was categorized as non, weak, moderate, or strong based on OD values relative to the negative control.

Genotypic detection of icaA and icaB genes

Genomic DNA was extracted using the HiPurA™ Bacterial Genomic DNA Purification Kit (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India). Real-time PCR was performed using gene-specific primers and Hi-SYBr Green master mix (HiMedia Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India). Cycling conditions included initial denaturation at 94 °C (10 min), followed by 40 cycles at 94 °C (10 s), 55 °C (45 s), and 72 °C (30 s).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the chi-square test (SPSS v25), and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant to determine the association between biofilm production and the presence of icaA and icaB genes.

In this study, 102 confirmed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates were analyzed to evaluate their biofilm-forming potential and the prevalence of the icaA and icaB genes associated with biofilm synthesis.

Phenotypic biofilm formation

Phenotypic assessment making use of the tissue culture plate (TCP) method revealed that 37 of the 102 MRSA isolates 37 (36.3%) exhibited biofilm-forming ability to varying degrees. Specifically, 16 isolates (15.7%) demonstrated strong biofilm production, 12 (11.8%) were moderate producers, and 9 (8.8%) were weak biofilm formers. The majority of isolates (n = 65; 63.7%) were non-adherent, showing no detectable biofilm production (Table 1).

Table (1):

Phenotypic Biofilm Formation in MRSA Isolates

| Biofilm Strength | MRSA isolates | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage (%) | |

| Strong Biofilm | 16 | 15.7 |

| Moderate Biofilm | 12 | 11.8 |

| Weak Biofilm | 9 | 8.8 |

| Non-Biofilm | 65 | 63.7 |

Genotypic detection of icaA and icaB genes

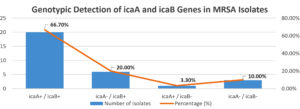

Genotypic screening by real-time PCR targeting the icaA and icaB genes showed that 20 (66.7%) isolates were positive for both genes. Notably, 6 (20.0%) isolates harboured only the icaB gene, and 1 (3.3%) isolate carried only icaA. A total of 3 (10.0%) isolates were negative for both genes (Figure 1).

The predominance of dual gene presence suggests a synergistic role of icaA and icaB in biofilm development, particularly in isolates with strong biofilm-forming phenotypes.

Correlation between gene presence and biofilm formation

A comparative analysis of gene presence and phenotypic biofilm strength revealed a strong correlation between icaA gene detection and high-level biofilm formation. Among the 16 strong biofilm producers, 14 were positive for icaA, and all were positive for icaB (Table 2). Interestingly, icaB was also detected in a subset of non-biofilm-producing isolates (n = 3), indicating that its presence alone may not be sufficient to drive biofilm formation in the absence of icaA (Figure 2). This suggests a primary role for icaA in the initiation of biofilm synthesis, with icaB likely contributing to PIA modification and structural reinforcement.

Table (2):

Correlation Between Biofilm Formation and icaA/icaB Gene Presence

Biofilm Strength |

icaA Positive |

icaA Negative |

icaB Positive |

icaB Negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Strong Biofilm |

14 (70%) |

3 (15%) |

20 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

Moderate Biofilm |

4 (20%) |

1 (5%) |

4 (20%) |

1 (5%) |

Non-Biofilm |

0 (0%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (15%) |

0 (0%) |

This study highlights a significant correlation between the presence of the icaA gene and strong biofilm formation among MRSA isolates, reinforcing its critical role in initiating the synthesis of the polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA) that constitutes the biofilm matrix. Consistent with our findings, recent studies have demonstrated that icaA-positive S. aureus strains exhibit enhanced adherence and biofilm density due to active production of PIA. A study by Armoon et al.17; Alibegli et al.,12 confirmed that icaA expression was significantly associated with increased biofilm biomass and structural integrity in clinical MRSA isolates, particularly in device-associated infections.17 This finding also aligns with the study by Manandhar et al., who reported that icaA-positive MRSA isolates exhibited significantly enhanced biofilm formation.15 Similarly, Nourbakhsh and Namvar found that 70% of biofilm-forming MRSA isolates in their study were icaA-positive, further emphasizing the gene’s central role in biofilm development.18,19

In contrast, the detection of isolates carrying icaB without icaA suggests the presence of ica-independent or compensatory pathways for biofilm formation. The icaB gene encodes a deacetylase that modifies PIA, enhancing its adhesive capacity, but alone may not initiate biofilm synthesis. This observation aligns with the findings by El-Jakee et al.,20 who found that icaB may stabilize the biofilm matrix but is unlikely to independently initiate biofilm formation.19 More recently, Rimi et al.13 also reported discrepancies between ica genotype and biofilm phenotype, demonstrating that some MRSA isolates carrying ica genes remained weak or non-biofilm producers. Moreover, studies by Cafiso et al. and Fitzpatrick et al. have highlighted that ica-independent mechanisms, such as the agr quorum-sensing system and sigB stress response pathways, can facilitate biofilm development, indicating that icaA-negative strains may still possess robust biofilm-forming capabilities.21,22

Moreover, the existence of weak or moderate biofilm-forming icaA-negative isolates supports the theory of alternative biofilm formation mechanisms. The agr quorum-sensing system, sarA regulon, and sigma factor B (sigB) have been implicated in ica-independent biofilm development. Study demonstrated that MRSA strains lacking icaA could still form biofilms through the action of surface-associated proteins such as fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBPs), clumping factors (ClfA/ClfB), and extracellular DNA release.22,23

Comparatively, this study’s findings align closely with investigations in developing countries, where a higher prevalence of icaB without icaA has been observed. This variation suggests potential environmental or geographical influences on MRSA biofilm-forming behaviors. For instance, studies in Iran and India have reported similar trends where icaB-positive strains were frequently found among non-biofilm producers, highlighting icaB‘s likely role in biofilm maturation rather than initiation. Additionally, the identification of icaA– / icaB+ isolates suggests that biofilm development in these strains may involve alternative pathways independent of the ica operon. A study by O’Gara has proposed that MRSA may utilize surface proteins like fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBPs) or clumping factor proteins (Clf) to promote biofilm formation in the absence of icaA.24 This alternative pathway may explain the presence of biofilm-forming icaA-negative isolates in this study. The findings underscore the importance of incorporating both phenotypic and genotypic methods for detecting biofilm-forming MRSA strains. Relying solely on genotypic screening for icaA and icaB may overlook ica-independent biofilm pathways, which could compromise diagnostic accuracy and hinder effective treatment strategies. These findings stress the importance of regional surveillance, as local environmental factors and antibiotic usage patterns may drive the evolution of distinct biofilm-forming strategies.

The clinical relevance of biofilm formation in MRSA cannot be overstated. Biofilm-associated infections are notoriously difficult to eradicate due to their resistance to antibiotics and immune clearance, often leading to chronic infections, treatment failures, and device-related complications. Therefore, combining phenotypic biofilm assays with genotypic screening for icaA and icaB provides a more comprehensive understanding of a strain’s biofilm-forming potential.

Overall, this study’s results contribute to the growing body of evidence indicating that icaA plays a crucial role in biofilm initiation, while icaB may serve more of a stabilizing function. The variability observed across different geographic regions and clinical settings highlights the need for region-specific surveillance to guide effective infection control practices and therapeutic interventions.

Routine screening of icaA and icaB genes in MRSA isolates should be integrated into clinical microbiology practices. Anti-biofilm agents and combination therapies should be explored to improve treatment outcomes for biofilm-associated MRSA infections. Further research should investigate alternative biofilm mechanisms to explore regulatory networks controlling ica expression, identify novel genes involved in ica-independent biofilm formation, and assess their implications in virulence, antimicrobial resistance, and persistence.

This study demonstrates a high prevalence of icaA and icaB genes among MRSA isolates from clinical samples, with a strong correlation between icaA presence and robust biofilm formation. While icaB appears to play a supporting role in biofilm maturation, it is insufficient in the absence of icaA. The presence of icaA-negative biofilm-forming isolates suggests alternative mechanisms are at play, highlighting the need for comprehensive diagnostic strategies that include both phenotypic and genotypic assessments.

These findings reinforce the clinical importance of biofilm detection in MRSA infections and advocate for the integration of biofilm-targeted diagnostics and therapeutics into infection control protocols. Continued research into ica-independent pathways may uncover novel targets for anti-biofilm therapies, offering promising avenues to manage persistent MRSA infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SGT University (IEC/FMHS/MD/MS/2023-27).

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrolling in the study.

- Tong SYC, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG Jr. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):603-661.

Crossref - Nikita, Mohan S, Kakru DK. Prevalence pattern, microbial susceptibility and treatment of MRSA in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Curr Adv Res. 2022;11(3):391.0087.

Crossref - Siddiqui AH, Koirala J. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. [Updated 2023 Apr 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2025.

- Mukim Y, Sonia K, Jain C, Birhman N, Kaur IR. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Pattern of MRSA amongst Patients from an Indian Tertiary Care Hospital: An Eye Opener. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2024;18(3):1700-1707.

Crossref - Otto M. MRSA virulence and spread. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14(10):1513-1521.

Crossref - Archer NK, Mazaitis MJ, Costerton JW, Leid JG, Powers ME, Shirtliff ME. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: properties, regulation, and roles in human disease. Virulence. 2011;2(5):445-459.

Crossref - Otto M. Staphylococcal Biofilms. In: Romeo T. (eds) Bacterial Biofilms. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, vol 322. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 2008;322:207-228.

Crossref - Folliero V, Franci G, Dell’Annunziata F, et al. Evaluation of Antibiotic Resistance and Biofilm Production among Clinical Strain Isolated from Medical Devices. Int J Microbiol. 2021;2021(8):9033278.

Crossref - Donlan RM, Costerton JW. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15(2):167-193.

Crossref - Lewis K. Persister cells, dormancy and infectious disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(1):48-56.

Crossref - Nguyen HTT, Nguyen TH, Otto M. The staphylococcal exopolysaccharide PIA – Biosynthesis and role in biofilm formation, colonization, and infection. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:3324-3334. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.10.027. Erratum in: Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;21:2035.

Crossref - Alibegli M, Bay A, Fazelnejad A, et al. Contribution of icaADBC genes in biofilm production ability of Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates collected from hospitalized patients at a burn center in North of Iran. BMC Microbiol. 2025;25:302.

Crossref - Rimi SS, Ashraf MN, Sigma SH, et al. Biofilm formation, agr typing and antibiotic resistance pattern of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from hospital environments. PLOS One. 2024;19(8):e11299820.

Crossref - Wang D, Wang L, Liu Q, Zhao Y. Virulence factors in biofilm formation and therapeutic strategies for Staphylococcus aureus: A review. Animals and Zoonoses. 2025;1(2):188-202.

Crossref - Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 36th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne, PA: CLSI. 2022. https://clsi.org/shop/standards/m100/

- Cramton SE, Ulrich M, Gotz F, Doring G. Anaerobic conditions induce expression of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect Immun. 2001;69(6):4079-4085.

Crossref - Armoon M, Babapour E, Mirnejad R, Babapour M, Taati Moghadam M. Evaluation of icaA and icaD Genes Involved in Biofilm Formation in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Clinical Sources Using Reverse Transcriptase PCR. Arch Razi Inst. 2024 Dec 31;79(6):1329-1335.

Crossref - Manandhar S, Singh A, Varma A, Pandey S, Shrivastava N. Evaluation of methods to detect in vitro biofilm formation by staphylococcal clinical isolates. BMC Research Notes. 2018;11(1):714.

Crossref - Nourbakhsh F, Namvar AE. Detection of genes involved in biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus isolates. GMS Hyg Infect Control. 2016;11:Doc7.

Crossref - El-Jakee J, Nagwa AS, Bakry M, Zouelfakar SA, Elgabry E, El-Said WAG. Characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus Strains Isolated from Human and Animal Sources. American-Eurasian J. Agric. & Environ. Sci.,2008; 4(2):221-229.

- Cafiso V, Bertuccio T, Santagati M, et al. agr genotyping and transcriptional analysis of biofilm-producing Staphylococcus aureus strains. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;51(1):220-227.

Crossref - Fitzpatrick F, Humphreys H, O’Gara JP. Evidence for icaADBC-Independent Biofilm Development Mechanism in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Clinical Isolates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43(4):1973-1976

Crossref - Schilcher K, Horswill AR. Staphylococcal Biofilm Development: Structure, Regulation, and Treatment Strategies. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2020;84(3):mmbr.00026-19.

Crossref - O’Gara JP. ica and beyond: biofilm mechanisms and regulation in Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;270(2):179-188.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.