ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

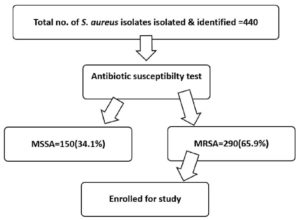

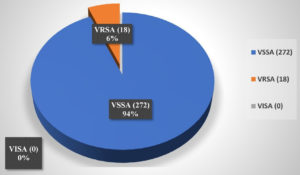

In recent years, the cases of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) have increased worldwide. The overuse of vancomycin has significantly contributed to the emergence of VRSA, a serious public health concern. This study aimed to observe the trends of VRSA in the Indian population. This study was conducted with 440 S. aureus clinical isolates at a tertiary care centre. The study processes samples through several stages: isolating and identifying S. aureus, screening for MRSA and VRSA, performing antibiotic susceptibility testing, differentiating between VISA and VRSA, extracting DNA, and detecting vanA and vanB genes via the PCR method. Among the isolated S. aureus (440), 150 (34.1%) were MSSA, and 290 (65.9%) were MRSA. From the 290 MRSA isolates, 272 (93.8%) were VSSA strains, while 18 (6.2%) were VRSA. No strains of VISA were isolated. In the genotypic analysis of VRSA strains, the proportion of the vanA gene was 33.33%, while the vanB gene was found in 11.11%. These findings emphasize the emergence of VRSA strains in community-acquired infections. The isolation of these resistance genes in our research is alarming, as it suggests the potential transmission of vancomycin resistance genes within Staphylococcus aureus populations. Understanding the patterns of vanA and vanB gene spread in VRSA strains is crucial for developing targeted interventions and a nationwide surveillance program.

Vancomycin-resistant S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus, VRSA, VISA, MRSA, vanA Gene, vanB Gene, Vancomycin-resistant Gene

Over the years, clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus have increasingly shown reduced sensitivity to vancomycin, with some even developing complete resistance.1 The first case of a methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strain with reduced vancomycin sensitivity was documented in Japan in 1997.2 This strain exhibited a slightly elevated minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for vancomycin, ranging between 3 and 8 µg/ml, and was termed vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA). Reports of VISA strains among MRSA isolates have since grown worldwide.3,4 Although these strains often displayed only moderately increased MIC values, their presence was frequently associated with vancomycin treatment failure.5 The first case of VRSA, characterized by a raised vancomycin MIC, was identified in the USA in 2002.1 When enterococci were shown to be resistant to vancomycin in the 1980s, it raised serious questions about whether vancomycin might be used to treat MRSA in the future.6

The incidence rates of VRSA strains vary across the globe. Before 2006, the prevalence was 2%, which increased to 5% between 2006 and 2014, and 7% between 2015 and 2020. The highest prevalence of VRSA has been reported in Africa at 16%, followed by Asia at 5%, North America at 4%, South America at 3%, and Europe at the lowest at 1%. Vancomycin resistance in S. aureus can be classified into two forms.7 The first, known as VISA, represents a moderate level of resistance. This type is associated with an altered cell wall, which causes the storage of acyl-D-alanyl-D-alanine residues that sequester glycopeptides after binding to it. The second, more advanced form of resistance is VRSA, which has the vanA operon, acquired by Enterococcus species through the transposon Tn1546.8

Decreased permeability plays an important role in the emergence of vancomycin resistance as it restricts the penetration of the drug to its intracellular target.5 Plasmid-mediated resistance genes like vanA, vanB, vanD, vanE, vanF, and others are thought to be spread from strains of Enterococci and represent another type of resistance.9 The primary aim of our study was to isolate and characterise the MRSA isolates and to demonstrate vanA and vanB genes among them.

We have collected 440 clinical specimens of S. aureus from different clinical departments of the institute for this cross-sectional study. Based on the power of 80% and a 95% confidence interval, a minimum of 384 samples was required; however, 440 samples were included to ensure adequate representation. Detailed patient information-including name, age, gender, department, clinical diagnosis, and other relevant details-was documented using a structured pro forma. The clinical samples were processed as follows.

Isolation & identification of Staphylococcus aureus

The sheep blood agar, MacConkey agar, and nutrient agar were used as media to culture the S. aureus species. After inoculation, the plate was incubated at 35-37 °C for approximately 16-18 hours. The colonies’ characters were studied, and biochemical tests, including catalase, tube coagulase, mannitol salt agar, and DNase, were performed. The identification of the isolates was further validated by an automated MALDI-TOF (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight) system. These isolates underwent a series of biochemical tests, using S. aureus ATCC 25923 as the control for their further analysis.

Screening of MRSA and VRSA strains

Identification of resistant strains was done with a 30 µg cefoxitin disc applied to Mueller-Hinton agar plates enriched with 4% sodium chloride. Based on CLSI guidelines, S. aureus strains with a zone of 21 mm or lower inhibition around a cefoxitin disc were classified as MRSA. S. aureus strains showing a zone of 16 mm or less with a 30 µg vancomycin disc were further categorized as VRSA.10 Additionally, vancomycin screen agar was used to detect growth of VRSA or VISA strains on the culture of S. aureus. If growth occurs in the vancomycin screen agar plate, these isolates are considered VRSA. They were further subjected to micro broth dilution to detect the MIC value.

The antibiogram

The antibiotic sensitivity of each Staphylococcus aureus isolate was evaluated by the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method with antibiotic discs containing amoxicillin, erythromycin, tetracycline, gentamicin, and cotrimoxazole. Its sensitivity interpretation was done on the following inhibition zone diameters: ≥20 mm for amoxicillin, ≥23 mm for erythromycin, ≥19 mm for tetracycline, ≥15 mm for gentamicin, and ≥16 mm for cotrimoxazole.

Differentiation of VISA/VRSA

Isolates were inoculated over the Vancomycin agar screen plate to identify VISA & VRSA subtypes. VISA and VRSA isolates were preserved in tryptic soy broth (TSB) supplemented with glycerol (20% concentration) and stored at approximately -70 °C until they underwent molecular characterization. Fresh isolates were obtained by subculturing these preserved items on Blood agar before proceeding with molecular characterization.

DNA Extraction and gene identification

DNA extraction from cultured isolates was done with the TRUPCR VRSA kit (v-1.0) as per the procedures provided with the kit. TRUPCR VRSA Detection kit (v-1.0) is a multiplex real-time PCR kit for the identification of resistance genes like vanA and vanB in cultured isolates, offering significant sensitivity and specificity. It is designed to detect VanA, VanB, and S. aureus in Texas Red/Orange, CY5/Red, and FAM/Green channels, respectively, with the internal control in the HEX/Yellow channel, with a single test tube.

Statistical analysis

Data were initially recorded in MS Excel and later added to SPSS software (v 26.0) for interpretation of data and its analysis. Numerical data were reported as mean values accompanied by standard deviations, whereas categorical data were described using frequencies and percentages. To assess differences between categorical variables, the chi-square test was considered, with a significance threshold of P ≤ 0.05.

In the studied sample (440) of Staphylococcus aureus isolates, analysis was done based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. On analysis, a total of 290 isolates (65.9%) of MRSA strains were identified (Figure 1).

Among the isolated MRSA strains, the majority were from male patients (55%), while females accounted for 45% of the cases. (male: female ratio-1.14:1). We found the maximum MRSA strains among the 31-40 year age group (19.3%) (Table 1). Most MRSA strains were recovered from patients in the inpatient department (IPD) at 41.5%, followed by the outpatient department (OPD) with 37.2%, the intensive care unit (ICU) at 16.5%, and the paediatric ICU (PICU) with 4.8% (Table 2). Maximum MRSA isolates were from the Department of General Medicine (28.9%), followed by the Department of General Surgery (23.44%) and the Department of Orthopaedics (17.9%) (Table 3).

Table (1):

Age-wise distribution of MRSA Cases

| Age group | MRSA | |

|---|---|---|

| Numbers | Percentage | |

| <1 year | 4 | 1.3% |

| 1-10 years | 16 | 5.6% |

| 11-20 years | 38 | 13.1% |

| 21-30 years | 48 | 16.6% |

| 31-40 years | 56 | 19.3% |

| 41-50 years | 42 | 14.4% |

| 51-60 years | 36 | 12.4% |

| 61-70 years | 30 | 10.3% |

| 71-80 years | 12 | 4.1% |

| 81-90 years | 8 | 2.7% |

| Total | 290 | |

Table (2):

Distribution of MRSA according to the source of the sample

Source of sample |

Number of samples |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

IPD |

120 |

41.5% |

OPD |

108 |

37.2% |

ICU |

48 |

16.5% |

PICU |

14 |

4.8% |

*IPD – in-patient department, *OPD – out-patient department, *ICU – intensive care unit, *PICU – paediatric ICU

Table (3):

Distribution of MRSA in different departments

Department |

No. of clinical isolates |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

OBS & Gynae |

16 |

5.5% |

Pediatrics |

18 |

6.2% |

Gen. Medicine |

84 |

28.9% |

Orthopedics |

52 |

17.9% |

Gen. Surgery |

68 |

23.44% |

Neurology |

16 |

2.75% |

CCM |

10 |

3.4% |

Ophthalmology |

10 |

3.4% |

Nephrology |

8 |

2.75% |

Urology |

8 |

5.5% |

Total |

290 |

Among all MRSA isolates, 46.8% were derived from pus samples, representing the highest percentage, followed by 18.60% from urine and 17.90% from blood. Other samples included tracheal aspirate (5.55%), sputum (4.13%), conjunctival swab (3.44%), pleural fluid (2.06%), and ascitic fluid (1.37%) (Table 4).

Table (4):

Distribution of MRSA among different clinical isolates

Type of samples |

Number of isolates |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

Urine |

54 |

18.60% |

PUS |

136 |

46.80% |

Sputum |

12 |

4.13% |

Blood |

52 |

17.90% |

Tracheal Aspirate |

16 |

5.55% |

Ascitic Fluid |

4 |

1.37% |

Pleural Fluid |

6 |

2.06% |

Conjunctival Swab |

10 |

3.44% |

Total |

290 |

In an antibiogram study, the maximum resistance for MRSA was found for penicillin (95.8%) and ciprofloxacin (91.7%), followed by levofloxacin (86.2%) and erythromycin (82.7%). Vancomycin resistance was found in 6.2% of clinical isolates. Vancomycin (93.8%), teicoplanin (96.5%), and linezolid (98.6%) were the most sensitive antibiotics. Table 5 displays the antibiotic resistance patterns of MRSA isolates, assessed using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion technique following CLSI recommendations.

Table (5):

Antibiotic Sensitivity Profile of MRSA Isolates (Antibiogram)

| MRSA Isolates (N = 290) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sensitive (in percentage) | Resistant (in percentage) | |

| Cefoxitin | 290 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 24 (8.27) | 266 (91.73) |

| Cotrimoxazole | 210 (72.41) | 80 (27.58) |

| Erythromycin | 50 (17.24) | 240 (82.75) |

| Clindamycin | 202 (69.65) | 88 (30.34) |

| Doxycycline | 246 (84.82) | 44 (15.18) |

| Vancomycin | 272 (93.7) | 18 (6.2) |

| Gentamicin | 248 (85.51) | 42 (14.5) |

| Levofloxacin | 40 (13.8) | 250 (86.2) |

| Linezolid | 286 (98.62) | 04 (1.38) |

| Teicoplanin | 280 (96.55) | 10 (3.45) |

| Penicillin | 12 (4.13) | 278 (95.86) |

| Tetracycline | 218 (75.17) | 72 (24.83) |

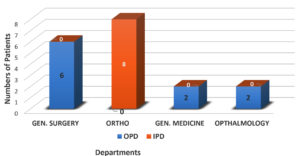

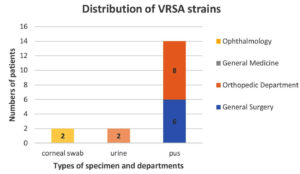

Among 290 MRSA clinical isolates, 18 isolates (6%) were found to be VRSA. There were no VISA strains in this study (Figure 2). Among the isolated VRSA, a maximum of eight (8) isolates were from the Orthopaedic department, and six (6) isolates were from the General Surgery department. Among the remaining four VRSA isolates, two were isolated from the general medicine department, while the other two were obtained from the Ophthalmology Department (Figure 3).

Among VRSA strains (n = 18), fourteen (14) were isolated from pus samples in the orthopaedic department (08) and the General Surgery department (06). The two (2) VRSA strains were isolated from urine specimens of the General Medicine Department, and the other two (2) were from the corneal swabs in the patients of the Ophthalmology Department (Figure 4).

Table 6 demonstrates the antibiotic susceptibility patterns of VRSA isolates as determined by the CLSI guidelines.

Table (6):

Antibiogram of VRSA isolates

Antibiotics |

Sensitivity fraction |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

Cefoxitin |

00 |

00 |

Ciprofloxacin |

04/18 |

22.22% |

Cotrimoxazole |

18/18 |

100% |

Erythromycin |

00 |

00 |

Clindamycin |

12/18 |

66.66% |

Doxycycline |

16/18 |

88.88% |

Vancomycin |

00 |

00 |

Gentamicin |

18/18 |

100% |

Levofloxacin |

04/18 |

22.22% |

Linezolid |

14/18 |

77.77% |

Teicoplanin |

12/18 |

66.66% |

Penicillin |

00 |

00 |

Tetracycline |

14/18 |

77.77% |

All isolated VRSA specimens underwent PCR analysis to analyse vanA and vanB resistance genes. Among these, six clinical isolates tested positive for either vanA, vanB, or both. Specifically, two isolates carried only the vanA gene, while both vanA & vanB genes were present in four isolates. Consequently, the prevalence of the vanA gene was 33.33%, and that of the vanB gene was 22.22% (Table 7).

Table (7):

Molecular characterization of isolated VRSA

| Genotype | Total No. of isolates | Serial Number of isolates | Gender | Department | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vanA | 6 | 3 | F | Gen. Medicine | U |

| 9 | M | Gen. Medicine | U | ||

| 4 | F | Gen. Surgery | P | ||

| 15 | M | Gen. Surgery | P | ||

| 6 | M | Orthopaedics | P | ||

| 11 | M | Orthopaedics | P | ||

| vanB | 4 | 6 | M | Orthopaedics | P |

| 11 | M | Orthopaedics | P | ||

| 4 | F | Gen. Surgery | P | ||

| 15 | M | Gen. Surgery | P |

*Gen. – General; *U – Urine; *P – Pus

The antimicrobial resistance of S. aureus poses a major challenge in human healthcare, as it spreads quickly and exhibits resistance to multiple antibiotics.11 Although MRSA was once thought to be exclusively linked to infections in healthcare settings, it is increasingly common for people, even without a history of exposure to healthcare systems, to get MRSA-associated community illnesses. MRSA contributes to greater morbidity and mortality, escalates healthcare costs, and poses a significant threat to global public health.12 In this study, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) accounted for 34.10% of isolates, while MRSA comprised 65.9%. These results align closely with those of Arora et al., who found MRSA prevalence of 64.8% in surgical units and 57.8% in orthopaedics wards.13 Similarly, Srinivasan et al. observed MRSA rates as high as 80% in their research.14 A meta-analysis by Savitha et al. from South India also reported an MRSA prevalence of 62.14%, comparable to our data.15

In our study group, 55% of MRSA isolates originated from male patients, resulting in a male: female ratio of 1.14:1. This aligns with findings by Lohan et al., who showed a higher prevalence of MRSA in males (67.9%) than in females (32.1%), corresponding to a sex ratio of 2.11:1.16 Research from Gujarat by Patel et al. demonstrated a similar distribution, with 56% male and 44% female patients, resulting in a sex ratio of 1.27:1. Comparable patterns were also reported by Rao and Srinivas in 2012.17

Pus was the most common clinical specimen yielding MRSA in multiple studies, including ours. Dar et al. found a high proportion of MRSA in pus samples in Aligarh (35.5%), while Srinivas et al. reported 64% in Andhra Pradesh, Tiwari et al. demonstrated 42% in Varanasi, and Rao and Mallick observed 61.4% in Maharashtra.18,19

In our study, the Surgical Department contributed the largest share of MRSA isolates at 52.34%. Similar findings are also published by Arora et al., with 54.8% MRSA prevalence in surgical units. And Lohan et al. observed that the majority of MRSA isolates were from surgical patients (59.9%), followed by ICU (24.6%), General Medicine (11.1%), and paediatrics (4.9%), which closely reflects our results.16

Penicillin is reported as the antibiotic with the highest resistance among MRSA strains, whereas vancomycin remains the most effective, as confirmed by numerous studies, including the present one. Mohit et al. from Uttar Pradesh observed complete resistance to penicillin in all MRSA isolates, followed by a 76.4% resistance rate to ciprofloxacin. A lower resistance pattern was observed with Minocycline (6.7%), Vancomycin (5.6%), and linezolid (4.5%).17 Prashant et al. reported that all MRSA isolates were resistant to penicillin and cloxacillin, while 80.5% also exhibited resistance to ciprofloxacin.20 On the other hand, vancomycin demonstrated complete effectiveness, with no resistance detected (0.0%). Among the antibiotics with the least resistance were chloramphenicol (17.9%) and gentamicin (27.4%). These findings align closely with the outcomes of the present study. Similarly, Patel et al. reported that all MRSA isolates exhibited resistance to penicillin.21

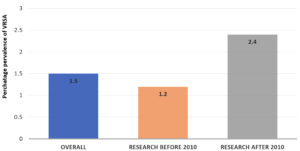

The global incidence of VRSA and VISA has been steadily rising. Various studies conducted worldwide have reported differing prevalence rates for these resistant strains. For example, in a study by Bamigboye et al., VRSA was detected in 1.4% of 73 clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates from a Nigerian hospital. In contrast, Dehbandi et al. reported a higher VRSA prevalence of 18.34%, along with VISA identified in 25% of 60 clinical S. aureus isolates.22 Shariati et al., in a meta-analysis, found a VRSA prevalence of 1.2% (95% CI) among 2,444 Staphylococcus aureus isolates collected before 2010. This number increased to 2.4% (95% CI: 1.4-3.5) in the period from 2010 to 2019, based on 3,411 isolates (Figure 5).23 In our study, VRSA was detected in 6% of the 290 MRSA isolates. No VISA strains were identified. Overall, VRSA accounted for 4.09% of the total 440 S. aureus isolates examined. A similar proportion of VRSA was isolated by Kejela et al., who found the prevalence of VRSA around 4.8% without VISA isolates.24

The distribution of VRSA in our clinical samples was comparable to that reported by Srinivasan et al., where 80% of isolates were from surgical units and 20% from medical units. Likewise, Hujer et al. found that 76% of MRSA isolates were sourced from surgical departments.25 Gohar et al. observed that VISA/VRSA strains were primarily obtained from pus associated with soft tissue and skin infections (75%), followed by blood (25%), similar to our study.26 Kejela et al. also reported 80% VRSA from the Surgical Department and 10% VRSA from the medical and paediatric departments in their study.24

Linezolid continues to be the preferred treatment option for MRSA strains that exhibit resistance to glycopeptide antibiotics like teicoplanin. The majority (88.9%) of VRSA isolates in this study exhibited susceptibility to both linezolid and teicoplanin. These findings are in accordance with data of Rajaduraipandi et al., who observed a 91.6% susceptibility rate in VRSA isolates.27 However, earlier studies-such as those conducted by Srinivasan et al. consistently observed complete susceptibility of VRSA strains to vancomycin and teicoplanin, suggesting a recent shift toward emerging resistance to these agents.14

In our study, 33.33% of VRSA isolates carried the vanA gene, and 22.22% harbored the vanB gene. Maharjan et al. from Kathmandu, identified vanA in 40% of isolates in their research, but did not detect vanB.28 Similar rates were observed in a study by Solhjoo from Iran, who identified these resistant genes in 34% (vanA) and 37% (vanB) of isolates.29 In another study by Wesam et al. reported the presence of the vanA gene in 16.67% and the vanB gene in 10% of VRSA isolates. Aubaid et al. also reported lower detection rates, with 6.9% of isolates carrying the vanA gene and 12.5% harboring the vanB gene.30

VRSA has shown a significant upward trend worldwide in recent years, a pattern that is also evident in India. The inappropriate use of antibiotics significantly drives antibiotic resistance in developing nations such as India. The problem is further intensified by the easy access to antibiotics without prescriptions, leading to their misuse and irregular treatment practices. The current study draws attention to the increasing incidence of both MRSA and VRSA within community settings.

This investigation identified the vanA gene in 33.33% of VRSA isolates and the vanB gene in 11.11% of them. This is an alarming sign. The MRSA antibiogram varies according to the patient’s regional and temporal characteristics. Therefore, to minimize resistance, it is essential to conduct susceptibility testing on all clinical isolates of S. aureus before initiating medication. Additionally, sustained monitoring of hospital-origin infections and regular evaluation of antimicrobial resistance trends are crucial measures in controlling the spread of MRSA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Administration of Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India, for their support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

G, NK, and KS conceptualized the study. G, KS, and NK performed literature review and data curation. G collected samples and performed the molecular detection. G and PD analyzed and interpreted the data. G, KS, and NK wrote the original draft. G, KS, NK, and PD reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee, Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India (letter no. 755/IEC/IGIMS/2022).

- Tenover FC, Biddle JW, Lancaster MV, et al. Increasing resistance to vancomycin and other glycopeptides in Staphylococcus aureus. Emerg Inf Dis. 2001;7(2):327-332.

Crossref - Hiramatsu K, Hanaki H, Ino T, Yabuta K, Oguri T, Tenover FC. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40(1):135-136.

Crossref - Howden BP, Davies JK, Johnson PD, Stinear TP, Grayson ML. Reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus, including vancomycin-intermediate and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains: resistance mechanisms, laboratory detection, and clinical implications. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(1):99-139.

Crossref - Linares J. The VISA/GISA problem: therapeutic implications. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7(Suppl 4):8-15.

Crossref - Susana Gardete, Alexander Tomasz, et al. Mechanisms of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(7):2836-2840.

Crossref - Sieradzki K, Roberts RB, Haber SW, Tomasz A. The Development of vancomycin resistance in a patient with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. N Engl J Med. 2019;340(7):517-523.

- Wu Q, Niloofar N, Wang Y, Hashemian M, Karamollahi S, Kouhsari E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of vancomycin-resistance Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10(1):101.

Crossref - Holden MTG, Feil EJ, Lindsay JA, et al. Complete genomes of two clinical Staphylococcus aureus strains: evidence for the rapid evolution of virulence and drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2004;101(26):9786-9791.

Crossref - Cetinkaya Y, Falk P, Mayhall CG. Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13.

Crossref - Naimi TS, LeDell KH, Como-Sabetti K, et al. Comparison of community- and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. JAMA. 2003;290(22):2976-84.

Crossref - Lakhundi S, Zhang K. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Molecular characterization, evolution, and epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;31(4):e00020-18.

Crossref - Tiwari HK, Sapkota D, Sen MR. High prevalence of multidrug resistant MRSA in a tertiary care hospital of Northern India. Infect Drug Resist. 2008;2008(1):57-61.

Crossref - Arora S, Devi P, Arora U, Devi B. Prevalence of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Northern India. J Lab Physicians. 2010;2(2):78-81.

Crossref - Srinivasan S, Sheela D, Shashikala, Mathew R, Bazroy J, Kanungo R. Risk factors and associated problems in the management of infections with methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2006;24(3):182-185.

Crossref - Savitha P, Swetha K, Beena PM. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Their Antibiotic Resistance Pattern Among Clinical Samples in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Rural South India. Asian J Adv Basic Sci. 2015;4(1):89-92.

- Lohan K, Sangwan J, Mane P, Lathwal S. Prevalence pattern of MRSA from a rural medical college of North India: A cause of concern. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(2):752-757.

Crossref - Patel FV, Thummar SG, Shah UV. A study of the prevalence of methicillin-resistance Staphylococcus aureus isolates from various clinical samples and its antibiogram in a tertiary care hospital. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol 2023;13(07):1488-1493.

Crossref - Dar JA, Thoker MA, Khan JA, et al. Molecular epidemiology of clinical and carrier strains of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in the hospital settings of north India. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2006;5:22.

Crossref - Mallick SK, Basak S. MRSA-Too many hurdles to overcome: A study from Central India. Trop Doct. 2010;40(2):108-110.

Crossref - Adhikari P, Basyal D, Rai JR, et al. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and multidrug resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical samples at a tertiary care teaching hospital: an observational, cross-sectional study from the Himalayan country, Nepal. BMJ Open. 2023;13(5):e067384.

Crossref - Kumar M, RK Goyal, Sardana V, Khan F. Resistance pattern of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from samples of critical care unit patients with special reference to inducible clindamycin resistance. Ind J Applied Res. 2023;13(06):19-21.

Crossref - Dehbandi N, Amoli RI, Oskoueiya R, Gholami A. The prevalence of vanA gene in clinical isolates of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a hospital in Mazandaran, Iran. Casp J Env Sci. 2019;17(4):319-325.

- Shariati A, Dadashi M, Moghadam MT, van Belkum A, Yaslianifard S, Darban-Sarokhalil D. Global prevalence and distribution of vancomycin resistant, vancomycin intermediate and heterogeneously vancomycin intermediate Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12689.

Crossref - Kejela T, Dekosa F. High prevalence of MRSA and VRSA among inpatients of Mettu Karl Referral Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2022;27(8):735-41.

Crossref - Huijer NSA, Sharif FA. Detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in nosocomial infections in Gaza Strip. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2008;2(9):235-241.

- Gohar NM, Balah MM, Sahloul N. Detection of Vancomycin Resistance among Hospital and Community-acquired Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates. Egypt J Med Microbiol. 2023;32(4):45-52.

Crossref - Rajaduraipandi K, Mani KR, Panneerselvam K, Mani M, Bhaskar M, Manikandan P. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a multicentre study. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2006 Jan;24(1):34-38.

Crossref - Maharjan M, Sah AK, Pyakurel S, et al., Molecular Confirmation of Vancomycin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus with vanA Gene from a Hospital in Kathmandu. Int J Microbiol. 2021;2021(4):38-47.

Crossref - Saadat S, Solhjoo K, Norooz-Nejad MJ, Kazemi A. VanA and VanB Positive Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Among Clinical Isolates in Shiraz, South of Iran. Oman Med J. 2014;29(5):335-339.

Crossref - Aubaid AH, Mahdi ZH, Abd-Alraoof TS, Jabbar NM. Detection of mecA, vanA and vanB genes of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Patients in Al Muthanna Province Hospitals. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine. 2020;14(2):32-36.

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.