Bacteriophages—viruses that specifically infect bacteria—have been central to major breakthroughs in molecular biology and medicine. Beyond their established role as antibacterial applications, recent research underscores their vast potential in fields such as genetic engineering, synthetic biology, space exploration, and the design of synthetic life. Phages demonstrate exceptional adaptability and utility across diverse disciplines. They contribute to combating antibiotic resistance, enable advanced gene editing and RNA-based technologies, and support the creation of designer genetic tools, programmable biomaterials, and engineered biological systems. In space biology, phages offer solutions for microbial control and astrobiological investigation. However, challenges such as scalable production, biosafety evaluation, and addressing ethical considerations remain. Bacteriophages represent transformative potential as tools for biotechnology and genetic innovation. Their expanding applications hold promise for advancing global health, environmental sustainability, and space research. Continued interdisciplinary research and development will unlock their full capabilities, paving the way for groundbreaking innovations in medicine, environmental management, and space exploration will be vital to fully realize their potential.

Bacteriophages, Phage Therapy, Biotechnology, Space, Synthetic Biology, Environmental Monitoring, Challenges

The viruses that infect and multiply within bacteria are called bacteriophages. They are found throughout nature and thrive in a variety of settings, including soil, water, and the human microbiome, where they are essential for controlling bacterial populations. These microbial predators are vital resources for ecological research, biotechnology, and medicine.1,2

The study Naureen et al. showed the natural control of bacterial populations by bacteriophages is important for maintaining balance in a variety of settings as ecological, such as soil, aquatic systems, and human-associated ecosystems.3 In natural ecosystems, phages contribute to biogeochemical cycling by lysing bacterial cells, releasing nutrients, and reallocating biochemical compounds.4 Since Felix d’Herelle (Father of first antibacterial therapy) showed the potential of phage therapy to treat dysentery in the early 20th century (1920s), this ability to regulate bacteria has been used in medicinal applications.5,6

Moreover, phages serve as mediators of microbial adaptation, evolving mechanisms to bypass bacterial defenses while exerting selective pressure on host populations. This coevolutionary arms race results in diverse bacterial and phage phenotypes, underlining their ecological importance.7

Phages have played an essential role in molecular biology and biotechnology in addition to therapy. They are extensively employed in bacterial typing, genetic engineering, and research, and they helped make important discoveries like Hershey and Chase’s (experiment conducted in 1952) proof that DNA is the genetic material.1,2 Through transduction and other forms of horizontal gene transfer, phages aid in the evolution of bacteria.3 These conventional functions highlight the significant contribution bacteriophages make to the advancement of both scientific and practical science.8

Beyond their conventional functions, bacteriophages have enormous potential in genetics and other uses.9 Phages have played a key role in genetics by helping to clarify basic biological processes. Phages were used in the Hershey-Chase experiment to prove that DNA is the genetic material.1,2 Additionally, phages influence bacterial development and genetic diversity by facilitating horizontal gene transfer through transduction.3 Synthetic biology and genome editing are two examples of the exact genetic changes made possible by this characteristic.6

Phages are used as delivery systems and diagnostic tools in non-traditional applications. Drug research, vaccine development, and biosensor design have all been transformed by phage display technology, which uses modified phages to show peptides or proteins.10 Because of their selectivity and adaptability, phages are also being investigated as nanotechnology platforms for cancer treatment and targeted drug delivery.4 Their adaptability is further shown by their promise in biocontrol to lower bacterial contamination in food and agriculture.2 These new functions demonstrate the revolutionary potential of bacteriophages in a variety of scientific and industrial fields.11

Bacteriophages, long recognized as key players in bacterial ecology, also hold immense potential for applied microbiology through their ability to modulate microbial populations and genetic pathways. Their precision in targeting bacterial hosts makes them valuable tools for microbial control, bioengineering, and therapeutic innovation. By bridging fundamental phage biology with applied microbial technologies, this study explores their expanding role beyond pathogens toward advancing biotechnology and environmental sustainability.

Despite challenges such as phage resistance and delivery optimization in vivo, phage therapy shows promise for bacterial infection control. This review explores the broadening horizons of phage applications, summarizing their roles in clinical and preclinical research, food safety, biotechnology, space exploration, and synthetic biology. It also catalogs FDA-approved products and global commercial initiatives harnessing phages’ potential.

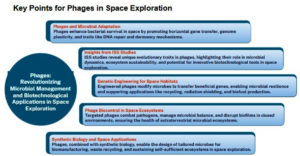

Phages in space exploration

Bacteriophages play a critical role in microbial adaptation and evolution, including in extreme environments such as space. Evidence from studies on the International Space Station (ISS) suggests that bacterial populations rapidly adapt to spaceflight conditions, with bacteriophage-associated genes significantly contributing to this process. Dormant prophages within bacterial genomes exhibit traits like enhanced DNA repair, antimicrobial resistance, and dormancy mechanisms, all of which improve bacterial survival in harsh environments.12

Under microgravity, phages contribute to microbial stability through several mechanisms. First, the lysogenic-to-lytic switch enables controlled bacterial turnover, preventing overgrowth and sustaining microbial balance within confined habitats. Second, phage-mediated horizontal gene transfer promotes genomic plasticity, enhancing the bacterial capacity to adapt to altered radiation levels, oxidative stress, and nutrient limitation in space. Third, phages influence quorum-sensing pathways and biofilm formation, stabilizing microbial communities on spacecraft surfaces. Collectively, these processes preserve ecosystem functionality and resilience under extraterrestrial stressors.

Moreover, phages influence microbial dynamics by shaping bacterial genome plasticity through rapid horizontal gene transfer and integration patterns. These adaptations allow bacteria to maintain functionality and resilience in stressful conditions, including the physicochemical extremes of space. Understanding these mechanisms offers insights into ecosystem sustainability in extraterrestrial environments and informs the development of phage-based biotechnological tools for space missions (Figure 1).7

Genetic adaptation of phages to survive space environments

Phages demonstrate remarkable genetic adaptability to survive and thrive in space environments. Studies on the ISS reveal that bacteriophages embedded in microbial genomes evolve novel traits, such as antimicrobial resistance, enhanced DNA repair, and dormancy mechanisms, enabling survival under microgravity and radiation. A genomic survey identified 283 prophages in spaceflight strains, with 21% being novel, highlighting the dynamic evolution of phage-host interactions.12

The adaptability of phages is further supported by their evolutionary strategies on Earth. Prophages favor integration into conserved chromosomal regions, maintaining co-orientation with replication forks to optimize host fitness. These integration hotspots suggest purifying selection for stability, favoring lysogeny over lytic cycles, which aligns with spaceflight conditions requiring genomic preservation.13

Additionally, phages impact ecosystem functions, enabling bacterial community adaptation in stressed environments, such as those on spacecraft. Their parasitic dynamics, often hijacked by phage satellites, further influence their evolutionary trajectory, presenting unique insights into genomic plasticity.6,14 Combining local and temporal adaptation data, phages display optimal infectivity against recently evolved bacterial hosts, reflecting rapid co-evolution in stressful settings.15 These findings collectively underscore phages’ adaptability, shaping microbiomes and offering tools for synthetic biology applications in extreme environments.16

Phages as tools for modifying microbial genomes for space habitats

Bacteriophages (phages) hold immense potential for genetic engineering in space habitats, leveraging their ability to modify microbial genomes. Engineered phages can facilitate microbial adaptation to space environments by transferring beneficial genes, including those for antimicrobial resistance, DNA repair, and metabolic resilience, which are crucial for survival in microgravity and radiation.12 Phages also drive microbial evolution through generalized and specialized transduction, enabling the transfer of adaptive genes across bacterial populations, thereby enhancing their functionality under space conditions.3

In space applications, phages can be engineered to modify microbes for bioregenerative life support systems, enabling efficient recycling, radiation shielding, and biofuel production.17 Their genetic engineering has already been applied to improve biofilm disruption, drug delivery, and vaccine development, opening new avenues for creating sustainable microbial ecosystems in space habitats.18 Phage-based approaches, combined with insights from the ISS microbiome studies, emphasize the potential of phages in developing self-sustaining microbial systems for long-term space exploration.19

Engineering phages for biocontrol and microbial management in extraterrestrial ecosystems

Engineered bacteriophages are promising tools for biocontrol and microbial management in extraterrestrial ecosystems. Their ability to target specific bacteria makes them invaluable for addressing pathogen outbreaks in closed environments, such as space habitats. Phages can be genetically engineered to enhance infectivity and specificity, enabling precise control of microbial populations and biofilm disruption.18,20 These modifications extend to targeted delivery of genes or antimicrobials, vital for maintaining microbial balance and combating resistant strains.21

Synthetic biology further amplifies phage utility, allowing the design of bespoke microbes suited to space conditions, from biomanufacturing to waste recycling.17,22 By understanding phage-host coevolution dynamics, as seen in environmental biotechnology systems, researchers can predict and manage microbial adaptability in extraterrestrial ecosystems.21 Overall, engineered phages are indispensable for sustaining microbial ecosystems in space exploration and colonization.

Phages in synthetic biology and genetic engineering

Synthetic biology has revolutionized phage engineering, enabling genome modifications for enhanced host specificity, antimicrobial delivery, and therapeutic applications. Engineered phages combat bacterial resistance, develop gene circuits, and facilitate directed evolution platforms.23,24 These advances optimize phage efficacy for targeting bacterial superbugs, cancer therapies, and vaccine development.18 Computational approaches further guide design, expanding phage utility in medicine and biotechnology.25

Leveraging phage genetics for CRISPR and genome editing technologies

Advances in phage genetics have facilitated the development of powerful genome-editing tools such as CRISPR-Cas systems, enabling precise and efficient modification of phage genomes.18,23 Genetic engineering approaches, including homologous recombination (HR), bacteriophage recombineering of electroporated DNA (BRED), and CRISPR-mediated editing, allow targeted gene knockouts, insertions, and deletions. These strategies have been successfully applied to modify Streptococcus thermophilus and Vibrio cholerae phages, enhancing their therapeutic and functional potential.23 Moreover, CRISPR systems help identify essential and dispensable phage genes, providing valuable insights into phage–host interactions and advancing the design of phage-based antibacterial therapies.26 Collectively, these tools are transforming the field of phage research, supporting innovations in synthetic biology applications, offering potential in biomedical engineering, nanomedicine, bacterial diagnostics, and material science.18,23,26

Phages as vehicles for horizontal gene transfer in synthetic microbial consortia

Bacteriophages (phages) are crucial mediators of horizontal gene transfer (HGT), shaping microbial community dynamics and driving bacterial evolution. In natural environments, such as the “pink berry” consortia, phages co-evolve with bacterial hosts, influenced by CRISPR-mediated interactions and transposon-driven gene transfers. This includes the horizontal transfer of a lysin gene to bacterial hosts, demonstrating phages’ evolutionary significance in natural systems.27

In wastewater environments, phages promote the extracellular release of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and plasmids during co-cultivation with microbes. This process facilitates ARG dissemination without relying on traditional conjugation, underscoring phages’ role in spreading antimicrobial resistance in municipal treatment plants.28 In human gut microbiomes, phage-mediated transduction facilitates HGT of antibiotic resistance, virulence factors, and pathogenicity determinants. Tailed bacteriophages, predominant in the gut, contribute significantly through specialized, generalized, and lateral transduction mechanisms.29

Synthetic biology advances have further empowered the manipulation of phages for various applications. Engineered phages now serve as programmable biomaterials, directed evolution platforms, and tools for microbial engineering, enhancing their utility in addressing global challenges like drug resistance and microbial infections.24

Phages as biomanufacturing and genetic tools

Bacteriophages are versatile tools in synthetic biology and genetic engineering. Phage-derived RNA technologies enable synthetic circuit design and directed evolution, offering insights into molecular biology and biological evolution.30 Genetically engineered phages, developed using synthetic platforms, combat bacterial superbugs and aid vaccine development.31 With high specificity and therapeutic potential, phages serve as “magic bullets” in healthcare.18 Advances in phage engineering continue to transform biology and medical research. Table 1 explores diverse phage-based technologies and their transformative potential across biomanufacturing, therapeutic development, and sustainable solutions, highlighting advancements in precision medicine and green biotechnology.

Table (1):

Innovative applications of phages in biotechnology and medicine

Application area |

Key technologies/approaches |

Benefits and impact |

|---|---|---|

Phages as biomanufacturing and genetic tools18, 30-31 |

Phage-derived RNA technologies, genetic engineering, directed evolution |

Unlocks insights into molecular biology, biological evolution, and therapeutic potential. Phages serve as versatile tools in synthetic biology for genome manipulation and protein engineering, enabling advancements in personalized medicine and biotechnology. |

Using phages in biomanufacturing32-33, 35 |

Genetic modification of microbes for enzyme and bioplastic production, gene transfer via phages |

Facilitates sustainable production processes by enhancing microbial genetic engineering. Phage tools promote eco-friendly manufacturing, reducing reliance on petrochemical-derived products while improving efficiency in bioplastic and enzyme production . |

Phage-based tools for precision editing of metabolic pathways36-38 |

Combination of phage integrases and CRISPR systems, base editors |

Enables precise microbial genome editing to improve biomanufacturing processes, increase product yields, and reduce waste. This approach is instrumental in metabolic engineering, offering breakthroughs in synthetic biology and industrial biotechnology. |

Microbiome manipulation39 |

Culture-independent techniques, multi-omics approaches |

Advances microbiome research by enabling precise microbiome modulation and providing a deeper understanding of microbial interactions. Phages help shape microbial communities, offering potential solutions for health, agriculture, and environmental challenges. |

Genetic engineering of phages for targeted drug delivery40-41 |

Engineered phages as nanocarriers, peptide libraries, hybridization with non-organic compounds |

Revolutionizes drug delivery systems by offering targeted bacterial infection treatment, cancer therapy, and vaccine development. Phages act as customizable carriers, ensuring reduced side effects and enhanced efficacy in pharmaceutical applications. |

Phages as therapeutic agents31,40 |

Phage therapy, genetically modified phages, targeting multidrug-resistant bacteria |

Provides an efficient alternative to antibiotics, especially for treating multidrug-resistant infections. Phages are adaptable and highly specific, making them promising tools in combating antibiotic resistance and advancing precision medicine. |

Phage-based vaccine development18,31 |

Engineered phages for vaccine delivery, immune system stimulation |

Enhances vaccine development by offering safer and effective alternatives with targeted immune responses. Phages stimulate immunity while being scalable and cost-effective, opening new avenues in prophylactic and therapeutic vaccine creation. |

Phage engineering for cancer treatment40-41 |

Engineered phages, gene delivery to cancer cells, oncolytic phages |

Offers cutting-edge cancer therapies with improved specificity for tumor targeting. Phages deliver therapeutic genes directly to cancer cells and act as oncolytic agents, reducing harm to healthy tissues and enhancing treatment outcomes. |

Phages in nanomedicine31,40 |

Phage-based delivery systems, hybrid nanocarriers, peptide-ligand modifications |

Provides innovative nanomedicine tools for safer, more efficient drug and gene delivery. Phages reduce cytotoxicity and improve bioavailability, offering solutions for challenging medical conditions, including genetic disorders and complex infections. |

Sustainable bioproduct manufacturing31,40 |

Phage-enhanced microbial systems, optimization of biomanufacturing processes |

Promotes eco-friendly and scalable production of bioplastics, enzymes, and other products. This supports green manufacturing and offers sustainable alternatives to traditional methods, contributing to a circular bioeconomy and reduced carbon footprint. |

Using phages to genetically modify microbes for biomanufacturing

Bacteriophages, highly specific to bacterial hosts, have emerged as critical tools for genetically modifying microbes for biomanufacturing applications such as enzyme and bioplastic production. Their unique ability to integrate into or lyse host genomes facilitates horizontal gene transfer, making them effective agents for microbial genetic engineering.32 Advances in synthetic biology and proteomics have further enhanced phage applications, enabling their use in bacterial detection, drug delivery, and diagnostic assays.33

Phages can be engineered to deliver recombinant gene payloads, influencing host-pathogen interactions and modulating bacterial behavior.34 This capability is pivotal for combating multidrug-resistant bacteria and enhancing sustainable production processes. Biomanufacturing processes for phages include optimized bacterial infection conditions, batch, and continuous production modes, and advanced purification techniques, ensuring scalable and efficient production.35 Phage-based innovations are transforming industries by providing sustainable solutions for bioproduct manufacturing, addressing public health challenges, and creating opportunities in synthetic biology. Their specificity and versatility position them as promising tools in biotechnology’s future landscape.33,35

Phage-based tools for precision editing of metabolic pathways

Phage-based tools have gained significant attention in metabolic engineering for their ability to precisely edit microbial genomes, enhancing biomanufacturing processes. One notable development is the combination of phage integrases with CRISPR systems for genome editing, allowing efficient insertion of large DNA sequences, such as the construction of a 13.9 kb heterologous operon and an 8.2 kb artificial operon in E. coli. This technique was employed in the construction of a uracil synthesis pathway, leading to a 160-fold improvement in production by adjusting glucose and bicarbonate levels.36 Moreover, engineered bacteriophages, such as those incorporating base editors, facilitate precise, single-nucleotide mutations without double-strand DNA cleavage, allowing for species- and site-specific editing in microbial communities. This approach provides a powerful tool for genetic interrogation and modification of complex microbial ecosystems.37 Additionally, phages can be engineered to enhance the specificity of Cas9 nuclease, enabling more focused genome editing, and contributing to the development of biotechnological applications for microbial management.38 These advancements make phages invaluable in synthetic biology, driving improvements in metabolic pathways for bioproduction.

Microbiome manipulation requires precision to avoid adverse effects, and phages offer a promising solution due to their host-specificity. Novel culture-independent techniques, alongside advanced culturing methods, allow deeper insights into gut bacteria’s physiology and interactions, offering more accurate identification of bacterial taxa through multi-omics approaches. These advancements help in understanding the functional traits of microbiota related to human health and disease, providing better tools for microbiome modulation.39

Genetic engineering of phages for targeted drug delivery systems in biotechnology

Bacteriophages have emerged as a promising platform for targeted drug delivery in biotechnology, leveraging their ability to selectively infect host bacteria. Unlike conventional drug delivery systems, which often face challenges like lack of specificity, cytotoxicity, and inefficient delivery, engineered phages provide a more precise and efficient solution. These phages can be genetically modified to serve as nanocarriers for drugs or genes, overcoming limitations seen with traditional nanocarriers.40,41

Phage-based delivery systems offer a variety of advantages, such as high host specificity, biocompatibility, and the ability to be engineered for precise targeting. They can be used to treat bacterial infections, including those caused by drug-resistant strains, and hold potential for applications in cancer therapy and vaccine development. Recent advancements in synthetic biology have enabled the design of genetically engineered phages with customized functionalities, such as peptide libraries and new targeting ligands, which enhance their ability to target specific cells and tissues. Additionally, hybridization with non-organic compounds has introduced new properties to phages, making them suitable for constructing bio-inorganic carriers.31,40,41

Phage-based delivery systems are not only innovative but also offer a safer, more efficient alternative for therapeutic applications, thus marking a significant advancement in nanomedicine.

Phages in environmental monitoring and genetic adaptation

Bacteriophages play a crucial role in ecosystem functions, influencing microbial community composition, genetic exchange, and environmental adaptation. They contribute to microbiome evolution, coping with environmental stress through mutualistic host relationships, enhancing ecosystem resilience, and biogeochemical cycling.7 Phages also control bacterial populations, facilitate horizontal gene transfer, and alter host metabolism, with significant implications for environmental studies.42 Additionally, filamentous phages have applications in ecorestoration, improving bacterial inocula and vegetation restoration efforts.43 Table 2 summarizes the diverse roles, applications, and advancements of bacteriophages in environmental science, highlighting their impact on microbial dynamics, ecosystem restoration, and bioremediation, with references to supporting studies.

Table (2):

Phages in environmental science: roles, applications, and future prospects

Aspect |

Key role of phages |

Applications |

Advancements |

Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Ecosystem functions7,42-43 |

Phages influence microbial community composition, genetic exchange, and adaptation. |

They play a crucial role in biogeochemical cycling and drive microbiome evolution in diverse ecosystems. |

Advances in understanding microbial-phage interactions enhance ecosystem resilience. |

Balancing phage-driven ecosystem manipulation without disrupting natural microbial dynamics. |

Environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling7, 44-45 |

Phages control bacterial populations and facilitate genetic exchange. |

Phages are used to gain insights into microbial genomes and ecosystem dynamics through eDNA analysis. |

Transformation of eDNA into active phages enables discovery of novel phages. |

Ensuring the accuracy and reliability of phage-based eDNA studies for consistent results. |

eDNA metabarcoding46 |

Phages detect rare and endangered species in diverse habitats. |

They enable biodiversity research and conservation efforts by non-invasively identifying species. |

Non-invasive metabarcoding methods protect ecosystems and preserve species integrity. |

Improving data accuracy and developing standard methods to increase reliability of results. |

Engineering phages47-48 |

Engineered phages modify gene expression in polluted environments. |

They address antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and reduce microbial contamination in water systems. |

CRISPR-Cas advancements enhance gene editing precision for targeted environmental repair. |

Overcoming limitations in phages’ ability to infect a broader range of microbial hosts. |

Biocontrol applications48-49 |

Phages serve as a biocontrol agent to mitigate microbial contamination. |

Engineered phage cocktails are used to control pathogens in water treatment systems effectively. |

Complementary infection strategies improve phage efficacy against resistant pathogens. |

Monitoring resistance development and minimizing unintended effects on beneficial microbes. |

Filamentous phages43 |

Phages promote microbial interactions and target specific bacterial strains. |

They facilitate ecosystem restoration and aid in vegetation recovery in degraded environments. |

Non-lethal engineering approaches allow phages to support sustainable ecological restoration. |

Reducing risks of ecosystem disruption caused by the introduction of engineered phages. |

Genetic modification for bioremediation 50-53 |

Genetically modified phages enhance microbial metabolic capabilities. |

They are used for the degradation of pollutants like heavy metals, synthetic chemicals, and hydrocarbons. |

Development of biosensors improves monitoring and efficacy of ecological restoration. |

Addressing ecological concerns and navigating regulatory hurdles for phage use in the environment. |

Pollution mitigation50,54 |

Phages are used to track and neutralize environmental contaminants. |

They provide cost-effective solutions for managing pollution in diverse ecosystems. |

Genetically engineered phages exhibit superior adaptability and efficiency in remediation. |

Minimizing adverse effects on non-target microbial communities in polluted environments. |

Synthetic biology51, 56 |

Phages serve as tools to advance biotechnological applications in synthetic biology. |

Tailor-made recombinant phages are designed for precise microbial community management. |

Innovations in synthetic biology expand the potential for sustainable environmental solutions. |

Addressing ethical dilemmas and overcoming technical complexities in engineering phage systems. |

Future potential51-56 |

Phages hold promises for sustainable environmental management and conservation. |

They contribute to enhanced microbial control systems and improved conservation practices. |

Biotechnological tools are continuously evolving, enabling new environmental applications. |

Evaluating long-term ecological impacts and ensuring collaboration across scientific disciplines. |

Phages as tools for environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling and monitoring microbial genomes

Bacteriophages are increasingly recognized as valuable tools for eDNA sampling, offering insights into microbial genomes and ecosystem dynamics. Phages influence microbial populations by controlling bacterial hosts, facilitating genetic exchange, and contributing to microbial community adaptation, which has been studied extensively in diverse environments.7 Recent advancements in phage-based methods have made it possible to transform eDNA into bacterial hosts, such as Escherichia coli, to generate active phages.44 This process has provided new avenues for phage discovery, highlighting the importance of eDNA as a source for identifying novel phages. Furthermore, the application of phages in eDNA sampling enhances our understanding of microbial biodiversity and community structure. Phage-based environmental monitoring can improve ecosystem assessments, offering a more comprehensive understanding of ecosystem functions and microbial interactions.45 By incorporating phages into environmental monitoring practices, we can advance conservation efforts, monitor wildlife health, and improve food production systems, ultimately contributing to better environmental management strategies. eDNA metabarcoding offers a non-invasive method for detecting rare and endangered species in aquatic ecosystems, aiding in biodiversity research and conservation. This innovative approach provides valuable insights into species composition without harming ecosystems or species, promising future advancements in environmental monitoring.46

Engineering phages to control microbial gene expression in polluted environments

Phage engineering, utilizing gene-editing technologies, presents a promising approach for controlling microbial gene expression in polluted environments. By manipulating bacteriophages, scientists can enhance their host range, improve efficacy, and produce phage-based drugs in a cell-free environment. Understanding bacteriophage-host interactions is critical for modifying or replacing receptor recognition proteins, enabling phages to infect a broader range of hosts. Advances in CRISPR-Cas systems and bacteriophage transcriptional assembly also play key roles in optimizing phage engineering for environmental applications.47

Phage-based biocontrol, specifically through engineered phage cocktails, has emerged as a viable strategy to mitigate microbial contamination in water systems. These cocktails, designed with complementary infection strategies, aim to reduce the impact of resistant pathogens in water treatment.48 Furthermore, bacteriophages can be employed to address environmental concerns like antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in wastewater treatment, enhancing microbial control without the adverse effects of traditional chemical methods.49

The potential of filamentous phages, which are non-lethal and can be engineered to target specific bacterial strains, also shows promise for ecorestoration. By promoting microbial interactions and nutrient cycling, these phages can aid in the restoration of vegetation and ecosystem health.43 Phage engineering, therefore, offers an innovative path for managing microbial communities in polluted environments, advancing both environmental and public health strategies.34

Potential for genetically modified phages in bioremediation efforts

Genetically modified bacteriophages hold significant potential in bioremediation efforts, offering innovative solutions for environmental restoration. Phages influence microbial community dynamics, metabolism, and genetic exchange, contributing to ecosystem resilience.7 Advances in synthetic biology have enabled the construction of genetically engineered phages for targeted pollutant degradation, surpassing natural strains in efficiency and adaptability.50,51

Recombinant phages can be tailored to enhance the metabolic capabilities of host bacteria, enabling effective bioremediation of heavy metals, synthetic chemicals, and hydrocarbons.51,52 Filamentous phages, in particular, show promise as biosensors and inocula, facilitating vegetation restoration and monitoring changes during ecological restoration.53 Moreover, engineered phages can track and neutralize contaminants, offering cost-effective solutions for polluted environments.50,54

Despite these advancements, challenges remain, including potential ecological impacts and regulatory hurdles.55 Continued research into phage-host interactions under stress conditions and the development of biotechnological tools will be critical to harnessing the full potential of genetically modified phages for sustainable environmental remediation.51,56

Collectively, these examples reflect the practical translation of phage research into environmental applications. Rather than a single case study, this section integrates multiple real-world examples across distinct ecological and industrial contexts—ranging from eDNA-based biodiversity monitoring and microbial biocontrol to bioremediation of pollutants and ecosystem restoration. These documented applications serve as functional case scenarios that demonstrate the feasibility and scalability of phage-based environmental innovations.7,42-56

Phages in education, art, and public outreach

Phages are being creatively integrated into education, art, and public outreach to promote understanding and acceptance of these fascinating viruses. Programs like “Phage Therapy Heroes” engage elementary students in interactive activities that showcase phage applications against bacterial infections, highlighting their societal benefits and addressing misconceptions about viruses.56 Initiatives such as BRIC (Bringing Research into the Classroom) bring bacteriophage research directly into classrooms, allowing students and teachers to isolate new phages and gain hands-on experience, which boosts scientific literacy.57 Bio-art also leverages phages’ biological properties to create art, blending science and culture in an innovative manner.55-61

An innovative approach to enhancing science education and public engagement is the genetic tagging of phages for visualization. By fluorescently labeling phages or introducing genetic tags, their behavior and interactions with bacterial hosts can be observed in real-time. This provides a dynamic visual representation of how phages target bacterial infections, reinforcing educational programs like “Phage Therapy Heroes”.56 In the BRIC program, genetically tagged phages enable K-12 students to isolate and study novel phages, offering authentic research experiences that deepen their understanding of microbiology.57-59 These visual techniques also complement advances in biotechnology, such as phage engineering, which fosters innovations in synthetic biology.60

Phage genetics has found an exciting medium in bio-art, transforming scientific concepts into creative visual narratives. Engineered phages, capable of expressing fluorescent proteins, have been used to create installations that visualize biological processes like gene expression, mutation, and viral replication. These projects not only inspire awe but also communicate the biomedical and ecological importance of phages, highlighting their role in combating antimicrobial resistance and advancing scientific fields.58-61 Phage-based bio-art thus bridges science, art, and public discourse, encouraging dialogue on the societal implications of genetic manipulation.60-63

Citizen science initiatives, like the Citizen Phage Library (CPL), have revolutionized phage research, enabling the isolation and characterization of over 1,000 phages since 2020. These contributions are essential in combating antibiotic resistance and creating personalized phage therapies for multidrug-resistant infections.18,64,65 Advances in genetic engineering have enhanced phages’ utility in diagnostics, biosensors, and synthetic biology, demonstrating their versatility in diverse applications.66

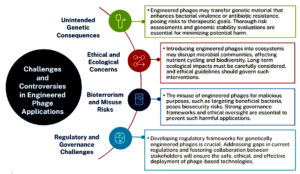

Challenges and controversies

The rapid advancements in genetic engineering and biotechnology bring transformative potential but also significant challenges and ethical concerns. While technologies like engineered bacteriophages offer innovative solutions to issues like antimicrobial resistance, they raise questions about safety, accessibility, environmental impact, and unintended consequences.67-71 These technologies demand robust ethical oversight and transparent decision-making to ensure they are used responsibly for societal benefit while mitigating risks (Figure 2).

One of the key risks with engineered bacteriophages is unintended genetic consequences. Despite their specificity, engineered phages can inadvertently transfer genetic material to bacterial hosts, potentially altering bacterial behavior or enhancing virulence. Horizontal gene transfer, as noted by Meile et al., could lead to the spread of harmful traits like antibiotic resistance.67 Additionally, recombinant gene payloads designed to enhance phage efficacy may have unpredictable interactions with human cells, complicating their clinical application.34 Furthermore, the dynamic co-evolution between phages and bacteria can lead to the emergence of phage-resistant bacteria, diminishing the long-term effectiveness of phage therapy.68

Ethical concerns also surround the manipulation of natural ecosystems. The genetic alteration of microbial communities through engineered phages may disrupt ecological balance, affecting nutrient cycling and biodiversity.70 Furthermore, the potential misuse of phage technology for bioterrorism or unethical purposes, such as targeting beneficial bacteria in agriculture, raises serious ethical dilemmas.67 Additionally, issues of consent and long-term environmental consequences must be considered when introducing genetically engineered organisms into natural habitats.69

In this context, adherence to appropriate biosafety standards is crucial. Research involving naturally occurring or genetically modified bacteriophages typically falls under Biosafety Level 1 (BSL-1) or Level 2 (BSL-2), depending on the host range and genetic modifications involved. Engineered phages carrying recombinant genes or targeting pathogenic bacterial strains require BSL-2 containment to prevent accidental release or cross-contamination. Proper risk assessment, facility containment measures, and personnel training are essential to ensure laboratory and environmental safety in compliance with international biosafety guidelines.71

To address these concerns, transparent governance frameworks and comprehensive risk assessments are crucial. Collaborative efforts between researchers, ethicists, and regulatory bodies are needed to balance innovation with regulation, ensuring the responsible and equitable application of engineered phages in combating antimicrobial resistance.71

Future directions and genetic frontiers

The future of genetic engineering, particularly in bacteriophage therapy, lies at the intersection of synthetic biology, genomic advancements, and innovative disease treatments. As antibiotic resistance escalates, bacteriophages have emerged as promising alternatives to traditional antimicrobial agents. With the rapid evolution of genetic engineering, especially synthetic biology, phages can now be designed with improved host ranges and tailored therapeutic payloads, thus optimizing their clinical efficacy.72 A key opportunity lies in using synthetic biology to develop phages that overcome challenges such as narrow host specificity and bacterial resistance.25

Future research will likely focus on enhancing phage genome engineering, incorporating computational tools to predict and design phages with ideal therapeutic characteristics.25 Additionally, synthetic biology has enabled phages to serve as scaffolds for biologically engineered materials, extending their use beyond therapy into broader biotechnological applications.73 The integration of engineered phages with modern medical strategies could revolutionize infection management, offering highly targeted treatments for multidrug-resistant pathogens.74

However, genetically engineered phages pose potential risks, particularly unintended genetic consequences. The interaction between engineered phages and bacterial hosts may lead to horizontal gene transfer, unintentionally passing on undesirable genetic traits, such as those associated with virulence or antibiotic resistance. Despite their specificity, phages may also infect non-target bacterial populations, disrupting local microbiomes or ecological dynamics.67 Recent advancements in synthetic biology improve the precision of these modifications, but they could still result in unexpected outcomes, such as altered pathogenicity or host specificity.34 Therefore, rigorous safety protocols, including comprehensive risk assessments, must be implemented during phage development and clinical trials.75

Moreover, the use of genetically engineered phages raises ethical concerns. Potential ecological disruptions, misuse in biowarfare, and issues of consent highlight the need for transparent regulations and governance to balance innovation with safety.76 Addressing these concerns will be crucial in ensuring the responsible, equitable application of engineered phages in combating antimicrobial resistance.25,30

Strengths and limitations

This review offers a comprehensive exploration of bacteriophages, emphasizing their roles in genetics, biotechnology, space exploration, and synthetic life. It highlights their potential in combating antibiotic resistance and advancing synthetic biology, including phage genome engineering and RNA-based technologies. The interdisciplinary approach connects molecular biology with clinical and futuristic applications, such as space exploration. However, the review lacks depth in certain areas, particularly in phages’ roles in space exploration and agricultural biotechnology, without sufficient case studies or data. Ethical and regulatory concerns are briefly discussed but not fully explored. The review also overlooks practical challenges, including scalability and genetic risks in biotechnology applications.

In conclusion, bacteriophages have evolved from simple bacterial predators to groundbreaking tools in genetics, biotechnology, and beyond. Their potential to combat antibiotic resistance, support space exploration, and contribute to synthetic biology and gene therapy highlights their transformative role. However, challenges such as ethical, ecological, and regulatory concerns must be addressed to fully realize their potential. With further research and interdisciplinary collaboration, phages can be optimized for applications in sustainable agriculture, nanotechnology, and extraterrestrial studies. A deeper understanding of phage biology will unlock new possibilities, driving innovation and providing solutions to pressing global challenges. Bacteriophages hold the key to advancing scientific frontiers and addressing critical societal needs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author would like to thank Shivani Chaudhary, Medquant Outcome Research LLP, for providing editing support.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Kasman LM, Porter LD. Bacteriophages.[Updated 2022 Sep 26]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2024.

- Microbe notes: Bacteriophage- Definition, Structure, Life Cycles, Applications, Phage Therapy. 2022. Accessed on December 29th, 2024. Please update URL: https://microbenotes.com/bacteriophage/

- Naureen Z, Dautaj A, Anpilogov K, et al. Bacteriophages presence in nature and their role in the natural selection of bacterial populations. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(13-S):e2020024.

Crossref - Doaz-Torres O, Lugo-Melchor OY, de Anda J, et al. Bacterial Dynamics and Their Influence on the Biogeochemical Cycles in a Subtropical Hypereutrophic Lake During the Rainy Season. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:832477.

Crossref - Summers WC. Bacteriophage therapy. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:437-51.

Crossref - Chanishvili N. Phage therapy—history from Twort and d’Herelle through Soviet experience to current approaches. In: Łobocka M, Slopek S, eds. Advances in Virus Research. Vol 83. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2012:3-40.

Crossref - Huang D, Xia R, Chen C, et al. Adaptive strategies and ecological roles of phages in habitats under physicochemical stress. Trends Microbiol. 2024;32(9):902-916.

Crossref - Jo SJ, Kwon J, Kim SG, Lee SJ. The Biotechnological Application of Bacteriophages: What to Do and Where to Go in the Middle of the Post-Antibiotic Era. Microorganisms. 2023;11(9):2311.

Crossref - Bisen M, Kharga K, Mehta S, Jabi N, Kumar L. Bacteriophages in nature: recent advances in research tools and diverse environmental and biotechnological applications. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024;31(15):22199-22242.

Crossref - Ali Y, Inusa I, Sanghvi G, Mandaliya VB, Bishoyi AK. The current status of phage therapy and its advancement towards establishing standard antimicrobials for combating multi drug-resistant bacterial pathogens. Microb Pathog. 2023;181:106199.

Crossref - Karn SL, Gangwar M, Kumar R, Bhartiya SK, Nath G. Phage therapy: a revolutionary shift in the management of bacterial infections, pioneering new horizons in clinical practice, and reimagining the arsenal against microbial pathogens. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1209782.

Crossref - Irby I, Broddrick JT. Microbial adaptation to spaceflight is correlated with bacteriophage-encoded functions. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):3474.

Crossref - Bobay LM, Rocha EPC, Touchon M. The adaptation of temperate bacteriophages to their host genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):737-751.

Crossref - Ibarra-Chavez R, Hansen MF, Pinilla-Redondo R, Seed KD, Trivedi U. Phage satellites and their emerging applications in biotechnology. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2021;45(6):fuab031.

Crossref - Koskella B. Bacteria-phage interactions across time and space: merging local adaptation and time-shift experiments to understand phage evolution. Am Nat. 2014;184(Suppl 1):S9-21.

Crossref - Batinovic S, Wassef F, Knowler SA, et al. Bacteriophages in Natural and Artificial Environments. Pathogens. 2019;8(3):100.

Crossref - Koehle AP, Brumwell SL, Seto EP, Lynch AM, Urbaniak C. Microbial applications for sustainable space exploration beyond low Earth orbit. npj Microgravity. 2023;9(1):47.

Crossref - Hussain W, Yang X, Ullah M, et al. Genetic engineering of bacteriophages: Key concepts, strategies, and applications. Biotechnol Adv. 2023;64:108116.

Crossref - Bijlani S, Stephens E, Singh NK, Venkateswaran K, Wang CCC. Advances in space microbiology. iScience. 2021;24(5):102395.

Crossref - Huss P, Raman S. Engineered bacteriophages as programmable biocontrol agents. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2020;61:116-121.

Crossref - Guerrero LD, Perez MV, Orellana E, Piuri M, Quiroga C, Erijman L. Long-run bacteria-phage coexistence dynamics under natural habitat conditions in an environmental biotechnology system. ISME J. 2021;15(3):636-648.

Crossref - Khalil AS, Collins JJ. Synthetic biology: applications come of age. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(5):367-379.

Crossref - Sun Q, Shen L, Zhang BL, et al. Advance on Engineering of Bacteriophages by Synthetic Biology. Infect Drug Resist. 2023;16:1941-1953

Crossref - Kumar A, Yadav A. Synthetic phage and its application in phage therapy. In: Łobocka M, Slopek S, eds. Phage Therapy – Part A. Vol 200 of Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2023:61-89.

Crossref - Lenneman BR, Fernbach J, Loessner MJ, Lu TK, Kilcher S. Enhancing phage therapy through synthetic biology and genome engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2021;68:151-159.

Crossref - Liu Y, Liang Z, Yu S, Ye Y, Lin Z. CRISPR RNA-Guided Transposases Facilitate Dispensable Gene Study in Phage. Viruses. 2024;16(3):422.

Crossref - Kosmopoulos JC, Campbell DE, Whitaker RJ, Wilbanks EG. Horizontal gene transfer and CRISPR targeting drive phage-bacterial host interactions and coevolution in pink berry marine microbial aggregates. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023:2023.02.06.527410. doi: 10.1101/2023.02.06.527410. Update in: Appl Environ Microbiol. 2023;89(7):e0017723.

Crossref - Wang Q, Wang M, Yang Q, et al. The role of bacteriophages in facilitating the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in municipal wastewater treatment plants. Water Research. 2025;268(Part B):122776.

Crossref - Borodovich T, Shkoporov AN, Ross RP, Hill C. Phage-mediated horizontal gene transfer and its implications for the human gut microbiome. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2022;10:goac012.

Crossref - Zhang W, Wu Q. Applications of phage-derived RNA-based technologies in synthetic biology. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 2020;5(4):343-360.

Crossref - Mitsunaka S, Yamazaki K, Pramono AK, et al. Synthetic engineering and biological containment of bacteriophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119(48):e2206739119.

Crossref - Elois MA, da Silva R, Pilati GVT, Rodriguez-Lazaro D, Fongaro G. Bacteriophages as Biotechnological Tools. Viruses. 2023;15(2):349.

Crossref - Abril AG, Carrera M, Notario V, Sanchez-Perez A, Villa TG. The Use of Bacteriophages in Biotechnology and Recent Insights into Proteomics. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(5):653.

Crossref - Schmitt DS, Siegel SD, Selle K. Applications of designer phage encoding recombinant gene payloads. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;42(3):326-338.

Crossref - Joao J, Lampreia J, Prazeres DMF, Azevedo AM. Manufacturing of bacteriophages for therapeutic applications. Biotechnol Adv. 2021;49:107758.

Crossref - Ta DT, Chiang CJ, Doan TT, Chao YP. Development of a genome engineering tool for insertion of pathway-sized DNAs in Escherichia coli. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2024;165:105776.

Crossref - Nethery MA, Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Roberts A, Barrangou R. CRISPR-based engineering of phages for in situ bacterial base editing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(46):e2206744119.

Crossref - Jia K, Cui YR, Huang S, Yu P, Lian Z, Ma P, Liu J. Phage peptides mediate precision base editing with focused targeting window. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1662.

Crossref - Mirzaei MK, Deng L. New technologies for developing phage-based tools to manipulate the human microbiome. Trends Microbiol. 2022;30(2):131-142.

Crossref - Karimi M, Mirshekari H, Basri SMM, Bahrami S, Moghoofei M, Hamblin MR. Bacteriophages and phage-inspired nanocarriers for targeted delivery of therapeutic cargos. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;106(Pt A):45-62.

Crossref - Wang H, Yang Y, Xu Y, et al. Phage-based delivery systems: engineering, applications, and challenges in nanomedicines. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22(1):365.

Crossref - Puxty RJ, Millard AD. Functional ecology of bacteriophages in the environment. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2022;71:102245.

Crossref - Sharma RS, Karmakar S, Kumar P, Mishra V. Application of filamentous phages in environment: A tectonic shift in the science and practice of ecorestoration. Ecol Evol. 2019;9(4):2263-2304.

Crossref - Karaynir A, Bozdogan B, Salih Dogan H. Environmental DNA transformation resulted in an active phage in Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2023;18(10):e0292933.

Crossref - Cook LSJ, Briscoe AG, Fonseca VG, Boenigk J, Woodward G, Bass D. Microbial, holobiont, and Tree of Life eDNA/eRNA for enhanced ecological assessment. Trends Microbiol. 2024;33(1):48-65.

Crossref - Sahu A, Kumar N, Singh CP, Singh M. Environmental DNA (eDNA): Powerful technique for biodiversity conservation. Journal for Nature Conservation. 2023;71:126325.

Crossref - Jia HJ, Jia PP, Yin S, Bu LK, Yang G, Pei DS. Engineering bacteriophages for enhanced host range and efficacy: insights from bacteriophage-bacteria interactions. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1172635.

Crossref - Hegarty B. Making waves: Intelligent phage cocktail design, a pathway to precise microbial control in water systems. Water Research. 2025;268(Part A):122594.

Crossref - Li Z, Liu B, Cao B, Cun S, Liu R, Liu X. The Potential Role of Viruses in Antibiotic Resistance Gene Dissemination in Activated Sludge Viromes. J Hazard Mater. 2024:0304-3894.

Crossref - Sagona AP, Grigonyte AM, MacDonald PR, Jaramillo A. Genetically modified bacteriophages. Integr Biol. 2016;8(4):465-74.

Crossref - Sharma S, Pathania S, Bhagta S, et al. Microbial remediation of polluted environment by using recombinant E. coli: a review. Biotechnol Environ. 2024;1:8.

Crossref - Rafeeq H, Afsheen N, Rafique S, et al. Genetically engineered microorganisms for environmental remediation. Chemosphere. 2023;310:136751.

Crossref - Morella NM, Gomez AL, Wang G, Leung MS, Koskella B. The impact of bacteriophages on phyllosphere bacterial abundance and composition. Mol Ecol. 2018;27(8):2025-2038.

Crossref - The phage: Engineered phages: The future of bioremediation?. 2023. Accessed on: December 28th, 2024. https://www.thephage.xyz/2023/11/25/engineered-phages-bioremediation/

- Mahdizade Ari M, Dadgar L, Elahi Z, Ghanavati R, Taheri B. Genetically Engineered Microorganisms and Their Impact on Human Health. Int J Clin Pract. 2024;2024:6638269.

Crossref - Breitbart M, Malki K, Sawaya NA, Bonnain C, Martin MO. Elementary Student Outreach Activity Demonstrating the Use of Phage Therapy Heroes to Combat Bacterial Infections. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2018;19(1):19.1.30.

Crossref - Brandl RL, Pavlovich CL, Pedulla ML. Bringing Research into the Classroom: Bacteriophage Discovery Connecting University Scientists, Students, and Faculty to Rural K-12 Teachers, Students, and Administrators. Journal of STEM Outreach. 2024;7(2).

Crossref - Brown N, Cox C. Bacteriophage Use in Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. In: Harper, D.R., Abedon, S.T., Burrowes, B.H., McConville, M.L. (eds) Bacteriophages. Springer, Cham. 2020.

Crossref - McCammon S, Makarovs K, Banducci S, Gold V. Phage therapy and the public: Increasing awareness essential to widespread use. PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0285824.

Crossref - Lemire S, Yehl KM, Lu TK. Phage-Based Applications in Synthetic Biology. Annu Rev Virol. 2018;5(1):453-476.

Crossref - Melkozernov AN, Sorensen V. What drives bio-art in the twenty-first century? Sources of innovations and cultural implications in bio-art/biodesign and biotechnology. AI & Soc. 2021;36:1313-1321.

Crossref - Harada LK, Silva EC, Campos WF, et al. Biotechnological applications of bacteriophages: State of the art. Microbiol Res. 2018;212-213:38-58.

Crossref - Wang M, Pang S, Zhang H, Yang Z, Liu A. Phage display based biosensing: Recent advances and challenges. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2024;173:2024.

Crossref - Citizen phage library: Deadly antibiotic-resistant bacteria killed by viruses from Citizen Science. 2024. Accessed on December 28th, 2024. https://www.citizenphage.com/news/2024-02-25.html

- Fletcher J, Manley R, Fitch C, et al. The Citizen Phage Library: Rapid Isolation of Phages for the Treatment of Antibiotic Resistant Infections in the UK. Microorganisms. 2024;12(2):253.

Crossref - Lobocka M, Dabrowska K, Gorski A. Engineered Bacteriophage Therapeutics: Rationale, Challenges and Future. BioDrugs. 2021;35(3):255-280.

Crossref - Meile S, Du J, Dunne M, Kilcher S, Loessner MJ. Engineering therapeutic phages for enhanced antibacterial efficacy. Curr Opin Virol. 2022;52:182-191.

Crossref - Ensure ias: Ethical challenges in genetic engineering and biotechnology. 2024. Accessed on: 28th December 2024. https://www.ensureias.com/blog/ethicss/ethical-challenges-in-genetic-engineering-and-biotechnology

- Geekforgeeks: Ethical issue related to genetically modified organisms. 2024. Accessed on: 28th December 2024. https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/biology/ethical-issues-related-to-modified-organisms/

- Rothschild J. Ethical considerations of gene editing and genetic selection. J Gen Fam Med. 2020;21(3):37-47.

Crossref - Science of Bio Genetics: Genetic Engineering – The Ethical Debate and Potential Risks of a Brave New World. 2024. Accessed on 28th December 2024. https://scienceofbiogenetics.com/articles/genetic-engineering-the-ethical-debate-and-potential-risks-of-a-brave-new-world

- Kilcher S, Martin J. Loessner, Engineering Bacteriophages as Versatile Biologics. Trends Microbiol. 2019;27(4):355-367, ISSN 0966-842X,

Crossref - Kim BO, Kim ES, Yoo YJ, Bae HW, Chung IY, Cho YH. Phage-Derived Antibacterials: Harnessing the Simplicity, Plasticity, and Diversity of Phages. Viruses. 2019;11(3):268.

Crossref - Barbu EM, Cady KC, Hubby B. Phage Therapy in the Era of Synthetic Biology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8(10):a023879.

Crossref - Levrier A, Karpathakis I, Nash B, Bowden SD, Lindner AB, Noireaux V. PHEIGES: all-cell-free phage synthesis and selection from engineered genomes. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2223.

Crossref - Wu J, Gu N. New orientation of Interdisciplinarity in medicine: Engineering Medicine. Engineering. 2024;45:252-261.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.