ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Tobacco-related diseases are the foremost cause of death globally. This research investigates the impact of smoking on lung function and the colonization of respiratory pathogens in asymptomatic smokers. Forty male smokers and forty age-matched non-smoker controls aged between 25-45 years were recruited. Nicotine dependence was evaluated using the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence questionnaire, while cumulative tobacco consumption was measured in pack-years. Pulmonary function test (PFT) was performed and morning sputum samples were collected for the molecular detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis using the conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method. PFT parameters FVC (L), FEV1 (L), FEV1/FVC%, PEFR (L/m) and FER25-75% (L/s) were lower in smokers when compared to controls. H. influenzae was detected in 65% of smokers and 20% of controls, whereas S. pneumoniae was detected in 57.5% of smokers and 12.5% of controls. M. catarrhalis was detected 5% in only smokers. After sequencing, the identified virulent H. influenzae strain SC50876 was found in smokers. Through the application of multiple regression analysis, it was found that there are significant negative correlations between H. influenzae and both FVC and PEFR in individuals who smoke. This study provides novel evidence that smoking impairs lung function and promotes early colonization of the lower respiratory tract by Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis, particularly the virulent H. influenzae strain SC50876. Multiple regression analysis revealed a significant negative association between bacterial presence and FVC and PEFR in asymptomatic smokers, suggesting that such colonization may accelerate functional decline and contribute to the early development of respiratory disease in otherwise asymptomatic individuals.

Pulmonary Function Test, Nicotine Dependence, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Smokers

Chronic respiratory diseases, including COPD, lower respiratory tract infections and lung cancers, are among the foremost causes of mortality worldwide, ranking 3rd, 4th, and 5th, respectively.1 Tobacco smoke contains numerous harmful chemicals and is a well-documented contributor to the development and progression of these diseases. It often works in combination with air pollution, microbial infections, and genetic factors to exacerbate respiratory health issues. Cigarette smoke (CS) hampers the natural defense mechanisms of the lung by impairing mucociliary clearance,2 damaging the airway epithelial lining3 and weakening local immune responses.4 Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae), Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae), and Moraxella catarrhalis (M. catarrhalis) are the pathogens most often associated with lower respiratory tract infections related to smoking. While S. pneumoniae is usually harmless in the upper respiratory tract, smokers have weakened mucosal defenses, allowing the bacteria to migrate into the lower airways. In smokers, non-typeable H. influenzae (NTHi) shifts from benign to harmful pathogens, playing a major role in chronic bronchitis and COPD flare-ups.5-8 Similarly, M. catarrhalis thrives in environments exposed to smoke, contributing to excessive mucus production, reduced ciliary activity and emphysema-like changes in animal models.9,10 Sputum offers a simple and non-invasive sample for studying the lower airway as it contains mucus, host cells, and microbial DNA. Although traditional culture methods are still the diagnostic standard, they often fail to identify organisms that are difficult to grow. Molecular techniques, such as the (PCR) polymerase chain reaction, offer enhanced sensitivity and expedited results. By targeting specific genes—psaA for S. pneumoniae, ompP6 for H. influenzae, and MCAT for M. catarrhalis – researchers can accurately detect these pathogens. Subsequent sequencing further confirmed the species and identified differences at the strain level. Although there is increasing recognition of the significance of microbes in the lungs, limited research has investigated the association between microbial colonization and lung function. This leaves a significant gap in understanding whether the presence of respiratory pathogens differs between smokers and non-smokers. If so, whether this microbial difference contributes to early impairments in pulmonary function. Our study addresses this gap by pairing molecular detection of key respiratory bacteria in sputum from smokers with lung function testing using spirometry. By categorizing participants based on their smoking habits and nicotine dependence, we uncovered new early indicators, both microbial and functional, of tobacco-related lung injuries. This is the first study to assess molecular detection of early colonization of respiratory pathogens in an asymptomatic smoker’s sputum samples. This integrated approach offers a promising model for early risk prediction and developing disease preventing strategies.

Study Design and Population

This analytical cross-sectional study was conducted by the Departments of Physiology and Pulmonary Medicine at Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute, in collaboration with the Mahatma Gandhi Advanced Research Institute (MGMARI), Puducherry. Forty smokers and forty controls aged 25-45 years were recruited in each group using purposive sampling. The study was carried out between April 2023 and January 2025, during which biological samples were collected and wet-laboratory procedures were systematically performed.

Ethical approval and informed consent

Approval was granted by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute, Puducherry (Approval No.: Ph.D. Project/04/2019/003; Date of approval: 15 March 2023). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the study objectives and procedures in their native language.

Sample size calculation

In the research conducted by Pramanik et al., the determination of the sample size was achieved by evaluating the mean FEF25–75% values across the two groups. It was concluded that enrolling 40 participants in each group would be sufficient to identify the expected effect size, maintaining a 5% significance level and 80% statistical power.11

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study group included individuals who had been smoking tobacco products daily for at least one year (according to the WHO guidelines).12 Individuals with a history of respiratory illnesses (including asthma, COPD, bronchitis, tuberculosis, or COVID-19), those employed in environments with high dust exposure (such as textile mills, cement plants, or coal factories), those with inflammatory conditions or recent infections, and those receiving immunosuppressive treatment were not included in the study. Control participants were healthy, age- and BMI-matched non-smokers from the same community.

Nicotine Dependence and Pulmonary Function Testing

The smokers were assessed with the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence (FTND) to identify their nicotine addiction levels, and pack-year calculations were conducted to measure their tobacco exposure.

For all participants, measurements such as age, height, weight, and BMI were documented. Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) were performed using the MIR Spirobank Oxi spirometer in accordance with the ATS/ERS guidelines.13 The recorded parameters comprised forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), the FEV1/FVC ratio, peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR), and forced expiratory FER25-75%.

Sputum sample collection

On the same day, an early morning sputum sample was obtained from each participant and placed in a sterile container. The samples were then sealed in Zip lock biohazard covers, transported in an ice box, and stored at -80 °C until further analysis.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

From the sputum samples, genomic DNA was isolated by utilizing the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. The purity and concentration of the extracted DNA were evaluated using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. To identify specific respiratory pathogens, conventional PCR was conducted using a Biosystems Veriti 96-well thermal cycler. The primers used were species-specific and chosen based on prior research.14-16 The sequences of these primers and their respective amplicon sizes are detailed below.

S. pneumoniae (psaA)

Forward: 5′-GCCCTAATAAATTGGA GGATCTAATGA-3′

Reverse: 5′-GACCAGAAGTTGTATCTT TTTTTCCG-3′

Amplicon size: 114 bp

H. influenzae (Omp6 gene)

Forward: 5′-AACTTTTGGCGGTTACTCTG-3′

Reverse: 5′-CTAACACTGCACGACGGTTT-3′

Amplicon size: 351 bp

M. catarrhalis (MCAT gene)

Forward (MCAT1): 5′-TTGGCTTGT GCTAAAATATC-3′

Reverse (MCAT2): 5′-GTCATCGCTAT CATTCACCT-3′

Amplicon size: 140 bp

12.5 µL of RED Taq DNA Polymerase Master Mix, 1.0 µL of forward and reverse primers (2.0 µM), 8.5 µL of nuclease-free water, and 2.0 µL of DNA template made up the 25 µL PCR reaction mixture. The thermal cycling protocol comprised a 5-minute initial denaturation step at 95 °C, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 seconds, annealing at 62 °C for 30 seconds (for all primer sets), an extension at 72 °C for 1 minute, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 minutes. The amplified PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and then examined under a UV lamp with a Gel Documentation System (Bio-Rad, Inc., USA). After being purified, PCR-positive samples were sent to MedioMix in Bangalore, India, for Sanger sequencing. Accession numbers from PP792902 to PP792911 are assigned to the sequences that have been published in the NCBI GenBank database.

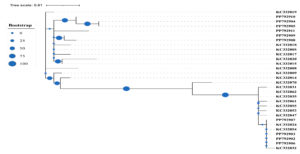

The phylogenetic tree (Figure) demonstrated distinct clustering of our study sequences (PP identifiers) with reference sequences (KC identifiers). Notably, PP792910, PP792904, PP792905, and PP792911 clustered tightly with KC332019, supported by high bootstrap values, indicating close genetic relatedness and confirming their taxonomic identity. Similarly, PP792907 and PP792908 grouped with KC332018, whereas PP792902, PP792903, and PP792906 formed a separate cluster with KC332032, also with robust bootstrap support. The presence of large bootstrap circles at major nodes reflects high confidence in the branching topology, suggesting that the observed clustering patterns are reliable. Conversely, a few nodes exhibited smaller bootstrap values, indicating less certainty in those particular evolutionary relationships. Overall, the analysis confirms that the majority of study sequences showed high concordance with established reference strains, thereby validating the accuracy of taxonomic assignments obtained through sequence analysis. S. pneumoniae and M. catarrhalis could not be amplified further due to inadequate DNA quantity or quality.

Figure. Phylogenetic analysis of Haemophilus influenzae isolates from smoker sputum samples. The maximum likelihood tree was constructed using study sequences (PP identifiers) and reference sequences (KC identifiers). Bootstrap support values are represented by circle sizes at nodes. Distinct clustering patterns confirm the taxonomic identity and genetic relatedness of the isolates, with PP792910, PP792904, PP792905, and PP792911 closely related to KC332019

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 26. Descriptive statistics were applied to summarize the physical parameters of the participants. The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Variables with a normal distribution were analyzed using t-tests (Welch’s t-test for unequal variances), while non-normally distributed data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Differences in physical characteristics between the study and control groups were assessed using the independent samples t-test. Pulmonary function test (PFT) parameters were compared between groups using Welch’s t-test. The prevalence of bacterial species detected by PCR was expressed as a percentage. To examine variations in PFT results based on the presence or absence of bacterial species within the smoker and control groups, the Mann–Whitney U test was employed. Furthermore, multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between PFT parameters and bacterial presence, while controlling for covariates.

Participant characteristics

There were no statistically significant differences in their age, height, weight, or BMI, as shown in Table 1.

Table (1):

Comparison of anthropometric parameters between smokers and controls

Anthropometric Parameter |

Smokers (n = 40) Mean ± SD |

Controls (n = 40) Mean ± SD |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

Age (years) |

40.5 ± 9.3 |

38.4 ± 8.1 |

0.3 |

Height (cm) |

167.4 ± 9.0 |

165.4 ± 7.4 |

0.3 |

Weight (kg) |

72.5 ± 14.5 |

68.5 ± 13.3 |

0.19 |

BMI (kg/m²) |

25.7 ± 4.3 |

24.9 ± 3.4 |

0.37 |

Independent t-test

Nicotine dependence and tobacco exposure

In the smoker cohort, the FTND scores revealed that 24 participants had low dependence (scores 1-2), 8 had low to moderate dependence (scores 3-4), 5 showed moderate dependence (scores 5-7), and 3 exhibited high dependence (scores 8-10).

Participants in the low dependence group had a median exposure of 5.0 pack-years (IQR: 2.5-7.5). Those in the low-to-moderate group had a similar but slightly broader range with a median of 4.5 pack-years (IQR: 2.5-9.5). The moderate dependence group showed a higher median exposure of 9.0 pack-years (IQR: 5.2-12.5). The high dependence group demonstrated the greatest cumulative exposure, with a median of 22.5 pack-years, indicating substantially heavier tobacco use. This exhibited a pattern of rising pack-years with increasing FTND scores.

Pulmonary function parameters

The pulmonary function of smokers was assessed in comparison to that of controls to determine the impact of smoking on respiratory performance. The results demonstrated that smokers exhibited significantly reduced pulmonary function parameters relative to the control group. Specifically, the FVC was lower among smokers (p = 0.03), as were the FEV1 (p = 0.002) and the FEV1/FVC% (p = 0.002). Furthermore, both the PEFR and the FER25-75% were markedly diminished in smokers (p = 0.0001), as depicted in Table 2.

Table (2):

Comparison of pulmonary function parameters between smokers and controls

Pulmonary function parameters |

Smokers (n = 40) Mean ± SD |

Controls (n = 40) Mean ± SD |

Levene’s Test (p) |

Welch’s t (df) |

p-value |

95% CI of Mean Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

FVC (L) |

3.2 ± 0.4 |

3.4 ± 0.5 |

0.083 |

-2.111 (78) |

0.03* |

[-0.47, -0.01] |

FEV1 (L) |

2.8 ± 0.4 |

3.0 ± 0.3 |

0.004 |

-3.157 (67.59) |

0.002* |

[-0.4, -0.09] |

FEV1/FVC% |

79.4 ± 4.5 |

82.1 ± 2.8 |

0.028 |

-3.189 (65.23) |

0.002* |

[-4.3, -1.0] |

PEFR (L/m) |

446.3 ± 74.3 |

509.6 ± 48.4 |

0.005 |

-4.513 (67.05) |

0.0001** |

[-91.2, -35.2] |

FER25-75% (L/s) |

2.7 ± 0.91 |

3.4 ± 0.7 |

0.498 |

-4.052 (78) |

0.0001** |

[-1.1, -0.37] |

Welch’s t-test

Molecular detection of respiratory pathogens

Table 3 presents the distribution of bacterial pathogens identified in both groups through PCR analysis. In the cohort of smokers, H. influenzae emerged as the most frequently detected species, identified in 26 cases (65%), followed by S. pneumoniae in 23 cases (57.5%), and M. catarrhalis in 2 cases (5%). In contrast, within the control group, H. influenzae was detected in 8 cases (20%), S. pneumoniae was identified in 5 cases (12.5%), while M. catarrhalis was not detected in any of the samples. Due to the low detection rate of M. catarrhalis, pulmonary function data were not analyzed in relation to its presence.

Table (3):

Molecular detection of respiratory pathogens among smokers and controls

Bacterial Species (expressed as %) |

Gene |

Smokers (n = 40) |

Controls (n = 40) |

|---|---|---|---|

S. pneumoniae |

PSaA2 |

23 (57.5%) |

5 (12.5%) |

H. influenza |

OMP6 |

26 (65 %) |

8 (20%) |

M. catarrhalis |

MCATI |

2 (5.0%) |

0 (0%) |

Percentage (%)

Lung function stratified by bacterial presence

To investigate the potential impact of bacterial colonization on lung function, the Mann–Whitney U test was employed to compare lung function metrics between smokers and non-smokers, categorized by the presence or absence of H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae. The findings indicated that the presence of either H. influenzae or S. pneumoniae did not have a significant effect on any of the assessed pulmonary function parameters (FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC%, PEFR, and FEF25-75%) in both the smoker and control groups. (Table 4)

Table (4):

Pulmonary Function Test Parameters in Smokers and Controls Stratified by bacterial presence and absence

Parameters/ Smokers |

S. pneumoniae (+) Median (IQR) n = 23 |

S. pneumoniae (-) Median (IQR) n = 17 |

P-value |

H. influenzae (+) Median (IQR) n = 26 |

H. influenzae (-) Median (IQR) n = 14 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

FVC (L) |

3.4 (2.9-3.6) |

3.3 (3.0-3.5) |

0.4 |

3.2 (2.8-3.4) |

3.5 (3.2-3.5) |

0.1 |

FEV1 |

2.9 (2.4-3.2) |

2.6 (2.4-2.9) |

0.09 |

2.6 (2.4-3.2) |

2.9 (2.5-3.1) |

0.75 |

FEV1/FVC% |

79.3 (76.5-82.3) |

80 (78-82) |

0.6 |

79.1 (77-81.9) |

80.2 (77-82) |

0.7 |

PEFR (L/m) |

455 (396-530) |

431 (396-482) |

0.3 |

431 (384-485) |

479 (409-530) |

0.12 |

FER25-75% (L/s) |

2.7 (2.3-3.5) |

2.6 (1.7-2.8) |

0.1 |

2.6 (2.5-3.3) |

2.7 (2.1-3.0) |

0.39 |

Controls |

n = 5 |

n = 35 |

P-value |

n = 8 |

n = 32 |

P-value |

FVC (L) |

3.7 (3.5-4.0) |

3.4 (3.0-3.8) |

0.23 |

3.1 (3.2-3.9) |

3.7 (2.8-3.4) |

0.06 |

FEV1 |

3.3 (2.9-3.4) |

3.1 (2.8-3.2) |

0.39 |

3.0 (2.7-3.3) |

3.1 (2.8-3.3) |

0.8 |

FEV1/FVC% |

81 (80-81) |

82 (80-84) |

0.19 |

80.0 (79.8-82) |

82 (80-84) |

0.18 |

PEFR (L/m) |

540 (474-540) |

504 (484-543) |

0.95 |

492 (467-509) |

519 (484-548) |

0.12 |

FER25-75% (L/s) |

2.4 (2.1-3.4) |

3.6 (3.0-40) |

0.12 |

2.7 (2.1-4.0) |

3.5 (3.0-40) |

0.17 |

Mann-Whitney U test

Regression analysis: bacterial presence and PFT parameters

The multiple linear regression analysis model utilized the presence of bacteria (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae; present/absent) as the main predictor, while accounting for covariates such as age, BMI, and smoking pack-years. A significant correlation was found between the presence of S. pneumoniae and an increase in FEV1 (p = 0.022). No other significant links were identified between S. pneumoniae and other PFTs. In contrast, H. influenzae was found to have a significant negative correlation with FVC (p = 0.01) and PEFR (p = 0.016). Although a negative relationship with FEF25-75% was noted, it did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.06) (Table 5).

Table (5):

Analysis of multiple linear regression examining the link between bacterial presence and PFT parameters, with adjustments made for age, BMI, and smoking pack-years

| PFT/Parameters | Group | S. pneumonia | H. influenza | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | |

| FVC (L) | 0.173 | 0.18 | 0.208 | 0.09 | -0.304 | 0.01* |

| FEV1(L) | 0.407 | 0.002* | 0.282 | 0.022* | -0.138 | 0.251 |

| FEV1/FVC% | 0.295 | 0.026* | -0.095 | 0.447 | 0.001 | 0.993 |

| PEFR (L/m) | 0.398 | 0.001* | 0.147 | 0.199 | -0.278 | 0.01* |

| FER25-75% (L/s) | 0.362 | 0.004* | 0.095 | 0.422 | -0.219 | 0.06 |

Multiple Linear Regression

Main findings

Our results confirm and refine the current evidence that cigarette smoking induces substantial impairment of pulmonary function. The decrease in FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC%, PEFR, and FEF25-75% in smokers, in comparison to controls, is congruent with previously established pathophysiological outcomes of long-standing tobacco exposure involving inflammation, airway remodelling, and epithelial injury.17-20

However, our study differs from previous studies in that it undertook, in a holistic fashion, the assessment of nicotine dependence stratification, pack-year history of tobacco exposure, and molecular characterization of bacterial colonization, providing a multidimensional perspective of early impairment of the respiratory tract in smokers.

In this study, the demographic similarities between the smoker and control groups bolster the internal validity of the results by mitigating potential confounding factors related to anthropometric differences.21 Previous studies have frequently categorized smokers as a homogeneous group.22,23 By employing the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), we offer a nuanced analysis of the dose–response relationship between lung function and tobacco exposure. Our results exhibited a pattern of rising pack-years with increasing FTND scores, reinforcing the connection between cumulative behavioral dependence and cumulative physiological burden.

Owing to the small sample size within each dependence category, this study did not stratify the pulmonary function results by FTND group. Nevertheless, the simultaneous reporting of FTND scores, pack-years, and lung function parameters lays a strong foundation for future investigations of the dose-dependent effects of tobacco exposure on pulmonary function using larger cohorts.

Additionally, our molecular detection of colonization of the respiratory tract offers new evidence of early bacterial penetration in asymptomatic smokers. Using PCR, we identified H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae in 65% and 57.5% of smokers, respectively, which were much higher than those in controls. This pattern is consistent with that of studies reporting increased nasopharyngeal colonization among smokers and passive smokers.24,25 However, our emphasis on colonization of the lower airway, in combination with measures of pulmonary function, fills a significant gap in our understanding of how microbial presence interacts with functional loss.

Novel findings and mechanisms

The current study’s stratified analyses did not identify any statistically significant variations in lung function related to the presence or absence of respiratory pathogens within each group. However, multiple regression analyses, adjusted for age, BMI, and pack-years, identified statistically significant negative associations between the presence of Haemophilus influenzae and certain pulmonary function parameters. This finding suggests that H. influenzae contributes to early subclinical airway obstruction, potentially through mechanisms involving mucosal inflammation and immune dysregulation.26-28

In contrast, S. pneumoniae was found to have a paradoxically positive association with FEV1 (p = 0.022). While this appears counterintuitive, we hypothesize that early colonization with S. pneumoniae in relatively healthier smokers may reflect an immune activation state that temporarily preserves or even augments certain lung function parameters before decline ensues, consistent with observations in studies of early COPD, where immune compensation precedes decompensation.29

Notably, M. catarrhalis was identified in only two of the 40 smokers and in no control subjects. This low prevalence differs from various studies presenting M. catarrhalis as a frequent airway colonizer in smokers and as a possible promoter of chronic bronchitis and emphysematous alterations, especially in the presence of smoke-induced epithelial impairment. The possible reason for the differing findings can be the overall health of the smoking population, which had not yet developed overt COPD or recurring exacerbations, and situations under which colonization by M. catarrhalis becomes more significant. Additionally, geographic, seasonal, and host immunity factors can affect colonization patterns.

Despite its low detection rate, the presence of M. catarrhalis exclusively in smokers suggests its potential as an opportunistic pathogen that favors tobacco-induced mucosal damage, particularly in more severe or active airway diseases.

Molecular insights

In smoker’s sputum samples, delineation of the H. influenzae strain SC50876 harboring the Outer Membrane Protein P6 (OMP P6), a conserved NTHi virulence factor, provides molecular depth to clinical evidence. NTHi strains have been increasingly described as long-term colonizers of chronic airway disorders such as COPD, bronchiectasis, and pneumonia.30,31 OMP P6 facilitates immune evasion by recruiting complement regulators and modulating TLR signals, thereby allowing bacterial persistence and host tissue destruction.32,33 Our identification of the respective genes confirms the proposition that even initial colonization by certain NTHi strains predisposes the respiratory tract to long-term pathology. The inability to amplify S. pneumoniae and M. catarrhalis from PCR-positive samples likely reflects the low DNA yield in sputum from asymptomatic individuals, a known challenge in molecular studies of airway colonization.

Implications and future work

Overall, our study presents a novel convergence of FTND and Pack years, clinical (PFT), and microbiological (PCR and sequencing) data, providing strong evidence that smoking impairs lung function and promotes early microbial colonization, which may accelerate functional decline. In contrast to prior research, which frequently investigated these variables independently, our stratified and integrative methodology provides a more comprehensive understanding of the pulmonary effects associated with smoking tobacco use.

The findings suggest that early bacterial colonization, particularly by H. influenzae, may interact with smoke-induced immune impairment to drive early subclinical obstruction. This has implications for early screening and preventive interventions in smokers before overt disease develops.

Study limitation

Limitations include the cross-sectional design and modest sample size, which limit causal inferences and stratified analyses by nicotine dependence category. Additionally, molecular detection was based on sputum, which may underestimate bacterial load. Future longitudinal studies using larger cohorts and advanced molecular methods could clarify temporal relationships between colonization, immune changes, and lung function decline.

The exclusion of female participants due to potential confounding limits the generalizability of our findings.

This study provides regionally relevant evidence that asymptomatic smokers exhibit early colonization of the lower respiratory tract by pathogenic bacteria—Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis—which is associated with measurable declines in lung function. By integrating behavioral indices of nicotine dependence, cumulative exposure in pack-years, spirometric assessment, and molecular pathogen detection with strain-level confirmation, this work demonstrates a novel analytical framework. Notably, the identification of the virulent H. influenzae strain SC50876 and its significant negative correlations with FVC and PEFR provides the first molecular–functional evidence linking tobacco exposure to early subclinical airway obstruction in this population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their gratitude to all the participants and laboratory technicians from MGMARI.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

NS conceived and designed the study and supervised the overall project. PJ and MA processed samples and contributed to PCR data acquisition. MS collected, analysed the data and interpreted the results. RG performed data visualization. PR provided clinical inputs and assisted in interpretation of respiratory findings.BS supervised the targeted molecular sequencing workflow. MS wrote the manuscript. RG edited the manuscript. NS approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Haemophilus influenzae isolate G10 outer membrane protein gene, partial cds NCBI GenBank under Accession No. PP79291. Additional data generated and analysed during the study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Research Institute (Approval No Ph.D. Project/04/2019/003; Date of approval: 15 March 2023).

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrolling in the study.

- World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death. August 7, 2024. Accessed Apr 2, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death

- Chethana R, Mishra P, Kaushik M, Jadhav R, Dehadaray A. Effect of Smoking on Nasal Mucociliary Clearance. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74(Suppl 2):956-959.

Crossref - Yeager RP, Kushman M, Chemerynski S, et al. Proposed Mode of Action for Acrolein Respiratory Toxicity Associated with Inhaled Tobacco Smoke. Toxicol Sci. 2016;151(2):347-364.

Crossref - Marseglia GL, Avanzini MA, Caimmi S, et al. Passive exposure to smoke results in defective interferon-g production by adenoids in children with recurrent respiratory infections. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29(8):427-432.

Crossref - Strzelak A, Ratajczak A, Adamiec A, Feleszko W. Tobacco Smoke Induces and Alters Immune Responses in the Lung Triggering Inflammation, Allergy, Asthma and Other Lung Diseases: A Mechanistic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(5):1033.

Crossref - Phipps JC, Aronoff DM, Curtis JL, Goel D, O’Brien E, Mancuso P. Cigarette smoke exposure impairs pulmonary bacterial clearance and alveolar macrophage complement-mediated phagocytosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 2010;78(3):1214-1220.

Crossref - Feldman C, Anderson R. The Role of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;37(6):806-818.

Crossref - Pinto M, Gonzalez-Diaz A, Machado MP, et al. Insights into the population structure and pan-genome of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Genet Evol. 2019;67:126-135.

Crossref - Yagyu K, Ueda T, Miyamoto A, Uenishi R, Matsushita H. Previous Moraxella catarrhalis Infection as a Risk Factor of COPD Exacerbations Leading to Hospitalization. COPD. 2025;22(1):2460808.

Crossref - Fischer K, Doehn JM, Herr C, et al. Acute Moraxella catarrhalis Airway Infection of Chronically Smoke-Exposed Mice Increases Mechanisms of Emphysema Development: A Pilot Study. Eur J Microbiol Immunol. 2018;8(4):128-134.

Crossref - Pramanik P, Ganguli IN, Chowdhury AR, Ghosh B. A study to assess the respiratory impairments among three-wheeler auto taxi drivers. Int J Life Sci Pharma Res. 2013;3(1):94-99.

- Fact sheet 2018 india. Heart disease and stroke are the commonest ways by which tobacco kills people. Accessed Apr 28, 2025 https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/b2aabbfd-40fb-4324-b530-a5192fbd53df/content

- Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Miller MR, et al. Standardization of Spirometry 2019 Update. An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Technical Statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(8):e70-e88.

Crossref - Abdoli S, Safamanesh S, Khosrojerdi M, Azimian A. Molecular Detection and Serotyping of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Children with Suspected Meningitis in Northeast Iran. Iran J Med Sci. 2020;45(2):125-133.

Crossref - Al-Buhilal JAM, Rhumaid AK, Al-Tabtabai AMH, AL-Rubaey NKF. Molecular detection of Haemophilus influenzae isolated from eye swabs of patients with conjunctivitis in Hilla Province, Iraq. J Appl Biol Biotech. 2022;10(2):168-172.

Crossref - Sheikh AF, Feghhi M, Torabipour M, Saki M, Veisi H. Low prevalence of Moraxella catarrhalis in the patients who suffered from conjunctivitis in the southwest of Iran. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):547.

Crossref - Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, et al. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932-946.

Crossref - Eisner MD, Balmes J, Katz PP, Trupin L, Yelin EH, Blanc PD. Lifetime environmental tobacco smoke exposure and the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Environ Health. 2005;4(1):7.

Crossref - Juniper EF, Wisniewski ME, Cox FM, Emmett AH, Nielsen KE, O’Byrne PM. Relationship between quality of life and clinical status in asthma: a factor analysis. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(2):287-291.

Crossref - Sorheim IC, Johannessen A, Gulsvik A, Bakke PS, Silverman EK, DeMeo DL. Gender differences in COPD: are women more susceptible to smoking effects than men? Thorax. 2010;65(6):480-485.

Crossref - Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(6):1324-1343.

Crossref - Fagerstrom K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(1):75-78.

Crossref - Benowitz NL. Nicotine addiction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2295-2303.

Crossref - Brook I, Gober AE. Recovery of potential pathogens and interfering bacteria in the nasopharynx of smokers and nonsmokers. Chest. 2005;127(6):2072-2075.

Crossref - Krone CL, Wyllie AL, van Beek J, et al. Carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae in aged adults with influenza-like-illness. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119875.

Crossref - Sapey E, Stockley RA. COPD exacerbations. 2: Aetiology. Thorax. 2006;61(3):250-258.

Crossref - Sethi S. Bacterial infection and the pathogenesis of COPD. Chest. 2000;117(5 Suppl 1):286S-91S.

Crossref - Bandi V, Apicella MA, Mason E, et al. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in the lower respiratory tract of patients with chronic bronchitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(11):2114-2119.

Crossref - Woodruff PG, Barr RG, Bleecker E, et al. Clinical Significance of Symptoms in Smokers with Preserved Pulmonary Function. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):1811-1821.

Crossref - Murphy TF. Respiratory infections caused by non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16(2):129-134.

Crossref - Pettigrew MM, Ahearn CP, Gent JF, et al. Haemophilus influenzae genome evolution during persistence in the human airways in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(14):E3256-E3265.

Crossref - Chen R, Lim JH, Jono H, et al. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae lipoprotein P6 induces MUC5AC mucin transcription via TLR2TAK1-dependent p38 MAPKAP1 and IKKβIκBαNF-κB signaling pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324(3):1087-1094.

Crossref - Swords WE, Buscher BA, Li KVS, et al. Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae adhere to and invade human bronchial epithelial cells via an interaction of lipooligosaccharide with the PAF receptor. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37(1):13-27.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.