ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a major cause of community- and hospital-acquired infections which poses serious therapeutic challenges. This study aimed to evaluate the resistance patterns and genomic characteristics of S. aureus isolates from a tertiary care hospital in India. A total of 3,266 clinical specimens were processed from January 2023 to December 2024, of which 425 (13%) were S. aureus. Among them, 55.2% were MSSA and 44.8% were MRSA. MRSA isolates were categorized as community-acquired (CA-MRSA, 82.14%) or hospital-acquired (HA-MRSA, 17.85%) based on clinical data. MRSA was most frequently isolated from pus (56.8%) and wound swab (33.6%) samples. Infections were more common in men and patients aged 41-60 years. The prevalence was significantly higher in patients with diabetes (30%) than in those without diabetes (9%) (p = 0.04). PVL was detected in 63.6% of MRSA, with higher expression in CA-MRSA. The mecA gene was found in 97% of MRSA isolates, whereas mecC was present in 1.5% of isolates. MRSA showed high resistance to penicillin (100%), ciprofloxacin (70.5%), and cotrimoxazole (60%), but remained sensitive to vancomycin. MDR was observed in 96% of MRSA and 18.1% of MSSA. Inducible clindamycin resistance was detected in 54.7% of MRSA isolates. Biofilm production was noted in 49.4% of MRSA isolates, with icaA and icaD genes detected in 19% of them (p = 0.001). This study highlights the high prevalence of CA-MRSA, with significant resistance patterns and virulence markers. Continued surveillance is essential for effective infection control and ensuring antibiotic stewardship.

Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA, MSSA, Antibiotic Resistance, Biofilm, mecA, PVL Gene, CA-MRSA, HA-MRSA, Tertiary Care Hospital

Staphylococcus aureus is a versatile gram-positive cocci commonly found as a commensal organism in the anterior nares, skin, and mucous membranes of healthy individuals. Despite its commensal nature, it is one of the most formidable pathogens in both community and hospital settings, responsible for an array of infections involving skin abscesses and other serious complications, such as bloodstream infections, systemic inflammation, bone infections, lung involvement, and endocarditis.1

Its pathogenic potential is attributed to a combination of virulence factors, including toxins, enzymes, biofilm formation, and, most notably, its capacity to rapidly acquire resistance to multiple classes of antimicrobial agents. The emergence and widespread proliferation of multidrug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus, most notably methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), pose a significant global health risk.

These strains exhibit resistance not only to beta-lactams but also to a wide range of antibiotics, such as macrolides, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and occasionally glycopeptides such as vancomycin.2 MRSA is associated with increased morbidity, prolonged hospitalization, higher treatment costs, and elevated mortality, making its surveillance and control a major concern in the healthcare system.

Phenotypic methods and automated systems are used to characterize antibiotic resistance in S. aureus for empirical and definitive therapy. However, the underlying genetic mechanisms responsible for resistance, such as heteroresistance or inducible resistance patterns, remain unclear.

However, although phenotypic identification is comfortable, discrepancies may arise due to the heterogeneous expression of resistance. The presence of these genes confers resistance and is often correlated with resistance to multiple other antibiotic classes owing to co-selection and plasmid-mediated resistance genes.

These genotypic insights not only complement phenotypic data but also allow for the early detection of emerging resistant clones, appropriate treatment of patients and their clinical improvement, timely initiation of infection control policies, and support targeted antibiotic stewardship efforts.3

Genotypic determinants of resistance genes, such as mecA (conferring methicillin- resistance), vanA/vanB (vancomycin resistance), erm (macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance) are recommended.

Vancomycin is the preferred antibiotic for severe MRSA infections. Phenotypically, VISA and VRSA are detected using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing.4 Genotypically, the detection of vanA, vanB, or related genes is necessary to confirm high-level resistance to vancomycin in clinical isolates.

The development of S. aureus strains with intermediate (VISA) and full resistance (VRSA) to vancomycin has become a growing concern in antimicrobial therapy. VISA strains often show thickened cell walls and altered peptidoglycan metabolism, leading to reduced susceptibility, whereas VRSA strains typically acquire vanA genes from vancomycin-resistant enterococci through horizontal gene transfer.

Resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and antibiotics in S. aureus is commonly mediated by erm genes. This resistance can be either constitutive (always expressed) or inducible (expressed only in the presence of an inducing agent, such as erythromycin).5

One of the key factors contributing to the pathogenicity and drug resistance of S. aureus is its ability to develop biofilms on both medical implants and host tissues, effectively hindering the action of antibiotics and supporting the survival of persister cells.

Among the virulence factors produced by S. aureus, Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) has garnered significant attention because of its association with enhanced pathogenicity, particularly in CA-MRSA (Community-Acquired Methicillin-resistant S. aureus) strains. PVL is a pore-forming bicomponent cytotoxin that targets and lyses polymorphonuclear leukocytes, contributing to severe inflammation and tissue necrosis.

Panton-Valentine Leukocidin (PVL)-positive strains are not reliable indicators of clinical outcomes in adult cases of staphylococcal pneumonia, musculoskeletal infections, or bloodstream infections. However, individuals with PVL-positive skin and soft tissue infections often have a higher likelihood of requiring surgical management. PVL has been associated with cutaneous and soft tissue infections in both methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) strains, regardless of their genetic lineage.6-8

Therefore, understanding the phenotypic and genotypic mechanisms underlying antimicrobial resistance in Staphylococcus aureus is crucial not only for guiding appropriate treatment strategies but also for enhancing infection control measures and minimizing the spread of resistant strains. This study aimed to comprehensively analyze both phenotypic resistance patterns and the prevalence of key resistance genes among clinical isolates of S. aureus, with a particular focus on MRSA. These findings will help strengthen antimicrobial stewardship efforts and improve clinical outcomes.

Aim

This study was designed to explore the resistance profiles and genomic features of S. aureus isolates recovered from clinical specimens within a tertiary care hospital.

Study Design

This cross-sectional observational study was conducted at the Department of Microbiology, Panimalar Medical College Hospital and Research Institute, from January 2023 to December 2024. After the Institutional Human Ethical Committee approval (PMCHRI-IHEC/MS/2023/58) was obtained.

Study setting and population

The study included all clinical samples (pus, blood, wound swabs, tissue biopsy, respiratory samples, and urine) received in the Microbiology Department from both the inpatient and outpatient departments during the study period. A total of 3266 clinical specimens were included from all age groups and both sexes, focusing on patients with clinically suspected Staphylococcus aureus infections. One isolate from each patient was included, and duplicates were excluded.

Sample collection, isolation and identification of Staphylococcus aureus

3266 consecutive clinical samples that met the study’s inclusion requirements and were available throughout a two-year period were used in this study. Following the standard microbiological method, the specimens were collected, inoculated in appropriate culture medium blood agar, chocolate agar and Mac Conkey agar, and then aerobically incubated at

37 °C. Gram staining, catalase, coagulase, and colony morphology were used to identify Staphylococcus aureus. Bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing were carried out using the VITEK 2 Compact automated system (bioMerieux). GP ID cards were used for the identification of Gram-positive isolates, while P628 cards facilitated antibiotic susceptibility profiling according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

All isolates (n = 425) were tested for methicillin-resistance using cefoxitin (30 µg) disc diffusion on Mueller-Hinton agar (HiMedia). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines M100, 2023 and 2024 for confirmation of Staphylococcus aureus.9

To assess inducible clindamycin resistance, the D-test was performed using the conventional disc diffusion technique (Kirby-Bauer). Discs containing erythromycin (15 µg) and clindamycin (2 µg) were positioned 15-20 mm apart (edge-to-edge) on Mueller-Hinton agar plates that were uniformly seeded with the test organism. Following incubation at 35 °C for 16-18 h, the appearance of a blunted or flattened zone of inhibition around the clindamycin disc adjacent to the erythromycin disc—resembling the shape of the letter “D” – was considered indicative of inducible resistance.9,10

Multidrug-resistance is described as resistance to three or more types of antimicrobial agents.11

All multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains were used for genotypic identification of 16S rRNA and confirmation of the resistance profile using mecA and mecC.

Standard microbiological procedures guided by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines M100, 2024 were used to ensure the reliability of the study findings by using the quality control strain S. aureus ATCC 25923.9,10

Phenotypic biofilm formation is usually detected via the microtiter plate assay, while genes such as icaA, icaD are genotypically associated with biofilm production were detected.12

Molecular Characterization

DNA extraction

A Staphylococcus aureus colony was grown in 1 ml TSB at 37 °C for 24 h. DNA extraction was performed using a QIAGEN minikit, as indicated by the manufacturer. Table 1 shows the primers used to detect the genes in this study.

Table (1):

Primer sequences, target genes, amplicon sizes, and references used for molecular detection of resistance, virulence, and biofilm-associated genes in Staphylococcus aureus by PCR

| Target gene | Purpose/Description | Primer sequence | Amplicon Size (bp) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mecA | Methicillin-resistance (MRSA) | F: AGAAGATGGTATGTGGAAGTTAG | 533 | 15 |

| R: ATGTATGTGCGATTGTATTGC | ||||

| mecC | Livestock associated MRSA | F: TCACCAGGTTCAACACAAAA | 356 | 10 |

| R: CCTGAATCTGCTAATAATATTTC | ||||

| PVL | Community-acquired MRSA | F: ATCATTAGGTAAAATGTCTGGACATGATCCA | 433 | 12 |

| R: GCATCAAGTGTATTGGATAGCAAAAGC | ||||

| 16S rRNA | Staphylococcus genus identification | F: GCAAGCGTTATCCGGATTT | 756 | 12 |

| R: CTTAATGATGGCAACTAAGC | ||||

| icaA | Biofilm detection | F: TCTCTTGCAGGAGCAATCAA | 188 | 19 |

| R: TCAGGCACTAACATCCAGCA | ||||

| icaB | Biofilm detection | F: ATACCGGCAACTGGGTTTAT | 141 | 15 |

| R: ATGCAAATCGTGGGTATGTGT | ||||

| icaC | Biofilm detection | F: CTTGGGTATTTGCACGCATT | 209 | 12 |

| R: GCAATATCATGCCGACACCT | ||||

| icaD | Biofilm detection | F: ATGGTCAAGCCCAGACAGAG | 198 | 14 |

| R: CGTGTTTTCAACATTTAATGCAA | ||||

| ermA | Macrolide resistance | F: TCTAAAAAGCATGTAAAAGAA | 645 | 14 |

| R: CTTCGATAGTTTATTAATATTAGT |

Gene targets

The presence of 16S rRNA, mecA, mecC, PVL, and icaA, icaB, icaC, icaD, erm genes was assessed using multiplex PCR for confirmation of S.aureus and MRSA, profiling the resistant genes, and biofilm-producing genes.

Optimization Strategies

Cycling conditions

PCR cycling parameters (annealing temperature, extension time) were adjusted to accommodate multiple primer pairs and ensure robust amplification of all targets.

Internal controls

Inclusion of internal controls (e.g., 16S rRNA) helps detect false negatives and ensures assay reliability.12 The test was validated using single and multiplex reactions, and all targets were efficiently and specifically amplified.

The target genes detected were 16S rRNA for S. aureus identification and confirmation, mecA for methicillin-resistance (MRSA) (3567810), mecC for livestock-associated MRSA, PVL for confirmation of CA-MRSA, icaA-icaD to detect biofilm producing strains, and ermA for macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance.13

The above gene detection and confirmation were performed under the PCR conditions of initial denaturation at 94-95 °C, 2-5 min, with primer concentration of 0.2-0.5 µM each, denaturation at 94-95 °C, 30 s, annealing at 50-60 °C, 30 s (optimized), extension at 72 °C, 30-60 s, with repeated cycles 25-35, final extension of 72 °C, 5-10 min.

Data analysis

The collected data were statistically analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), a comprehensive software tool for data management and analysis.

A total of 3266 patients samples were processed and analyzed from January 2023 to December 2024. Out of these samples, 13% (425) were Staphylococcus aureus. The culture isolates were classified as (55.2%) (n = 235) MSSA and (44.8%) (n = 190) MRSA. Of these, 82.14% were community-acquired and 17.85% were hospital-acquired MRSA.

Virulence-based analysis and genomic characterization were correlated with the demographic profile of each sample source.

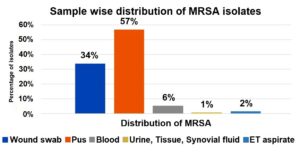

The majority of MRSA isolates were obtained from pus samples (57%), followed by wound swabs (34%), and to a lesser extent from blood (6%), ET aspirate (2%), urine, tissue, and synovial fluid (1% each). This highlights pus and wound swabs as the predominant sources of MRSA in this study (Figure 1).

The majority of MRSA isolates were obtained from pus samples (57%), followed by wound swabs (34%), and to a lesser extent from blood (6%), ET aspirate (2%), urine, tissue, and synovial fluid (1% each). This highlights pus and wound swabs as the predominant sources of MRSA in the study.

Among the age groups 41-60 years, 41% were suffering from the MRSA infection, which was predominant in male patients (Table 2).

Table (2):

Age and gender-wise distribution of HA-MRSA and CA-MRSA isolates

| Age group | HA-MRSA (n = 34) | CA-MRSA (n = 156) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| 21-40 | 8 | 3 | 23 | 18 |

| 41-60 | 12 | 6 | 39 | 31 |

| >60 | 3 | 2 | 25 | 20 |

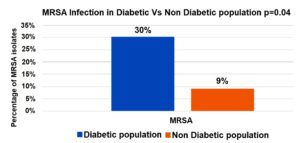

A significantly higher proportion of MRSA infections was observed in the diabetic population (30%) compared to the non-diabetic population (9%), with statistical significance (p = 0.04). This suggests that diabetes is a potential risk factor for MRSA infections (Figure 2).

All MRSA isolates were subjected to 16S rRNA gene specific primers and confirmed to be Staphylococcus aureus. Of the total MRSA infections, 82.14% were identified as community-acquired infections, indicating a significant prevalence in non-hospital settings, and 17.85% of the infections were hospital-acquired, suggesting a relatively lower incidence within the healthcare environment. CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA were initially categorized based on the clinical history and days of hospitalization of the patients. Among the 82.14%, n = 156 CA-MRSA, and in the 17.85%, n = 34 HA-MRSA.

Among the n = 190 MRSA, 121 were PVL gene positive (63.6%), (n = 101) 83.4% CA-MRSA and 16.5% were HA-MRSA (n=20) positive for PVL gene. Compared to methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA), which had a frequency of 18.12%, MRSA had a much higher prevalence of multidrug-resistance (MDR) 96%.

Methicillin-resistance was screened using Cefoxitin (30 µg) disc diffusion and Vitek 2 compact. Among the cefoxitin-resistant MRSA isolates, n = 6 (3.1%) were found to be oxacillin susceptible with MIC ≤4 µg/ml by Vitek 2 compact.

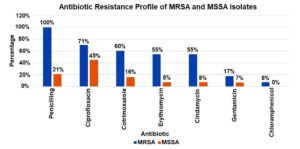

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed that MRSA isolates were 100% resistant to penicillin and cefoxitin, 70.5% to ciprofloxacin, 60% cotrimoxazole. Lower resistance was observed for gentamicin (17.4%) and chloramphenicol (7.9%), and all isolates remained sensitive to vancomycin. The mecA gene was positive among n = 182 (97%) MRSA isolates, while mecC gene was detected among n = 3 (1.5%) strains.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed that MSSA isolates exhibited 21% resistance to penicillin, with resistance rates to ciprofloxacin and cotrimoxazole of 45%, 16%, respectively. Resistance was observed for gentamicin (7.4%), and all isolates remained sensitive to vancomycin, linezolid, daptomycin, and teicoplanin (Figure 3).

MRSA isolates demonstrated the highest resistance to penicillin (100%), followed by ciprofloxacin (71%), cotrimoxazole (60%), erythromycin (55%), and clindamycin (55%). Lower resistance rates were observed for gentamicin (17%) and chloramphenicol (8%). In comparison, MSSA isolates exhibited significantly lower resistance across all tested antibiotics, indicating a distinct difference in resistance patterns between MRSA and MSSA strains.

Inducible Clindamycin resistance was found more in MRSA, n = 104 (54.7%) than in MSSA, n = 19 (8%). Molecular confirmation done with ermA gene detection in these strains, which was found to be 3%. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) was not isolated in this study.

Among MRSA isolates, hospital-acquired strains were found to be more resistant to antibiotics than community-acquired strains. The Chi-square test was employed for statistical analysis to assess the associations between variables, with the results detailed in Table 3.

Table (3):

Comparison of antibiotic resistance patterns between CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA isolates

Antibiotic |

CA-MRSA Resistance (%) |

HA-MRSA Resistance (%) |

p-value |

Statistical |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Oxacillin |

96.2 |

100 |

less than 0.001 |

Yes |

Ciprofloxacin |

8 |

5 |

less than 0.001 |

Yes |

Cotrimoxazole |

34 |

60 |

less than 0.001 |

Yes |

Erythromycin |

36 |

80.1 |

less than 0.001 |

Yes |

Gentamicin |

26.4 |

76.4 |

less than 0.001 |

Yes |

Clindamycin |

24 |

6 |

less than 0.001 |

Yes |

HA-MRSA isolates exhibited significantly higher resistance rates across all tested antibiotics compared to CA-MRSA isolates. Resistance to oxacillin was nearly universal in both groups; however, statistically significant differences (p < 0.001) were observed for ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, erythromycin, gentamicin, and clindamycin, indicating a more resistant profile in healthcare-associated MRSA strains

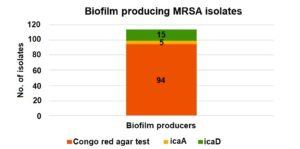

Nearly 94 strains (49.4%) of MRSA were biofilm producers by Congo Red agar method and were further confirmed genotypically. Biofilm producing intercellular adhesion genes icaA, icaB, icaC, icaD were detected in n = 23 (19%) of the above isolates. Of the 94 Congo Red agar test-positive MRSA isolates 23 carried biofilm-associated genes (icaA and icaD). This association was statistically significant (p 0.001), indicating a strong correlation between Congo red positivity and the presence of these genes (Figure 4).

Out of the total MRSA isolates, 94 were identified as biofilm producers by the Congo Red agar (CRA) test. Among these, only 5 and 15 isolates showed the presence of the icaA and icaD genes, respectively, indicating a limited genotypic correlation with phenotypic biofilm production.

A total of 425 (13%) Staphylococcus aureus were obtained from 3266 clinical samples. In our study, MRSA isolation was higher among the pus samples (56.8%), similar findings were observed in a study done by Lohan et al.16

The prevalence of S. aureus in pus samples may be due to skin commensals or wound exposure to environmental microbes. The ICMR Annual Report, 2022, reported an overall prevalence of 44.5% for MRSA, which is same as our study showing 44.8% (n = 190).17

A study by Raveendran et al. reported a higher incidence of MRSA isolates among males aged 50-60 years, which is consistent with our findings, where 41% (n = 78) of cases were observed in the 41-60 year age group.18

All HA-MRSA isolates showed 100% resistance to Penicillin and Cefoxitin, as documented in our study, and six CA-MRSA isolates (3.1%) were found to be oxacillin susceptible. 70.5% of MRSA isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin, which correlates with our study.12

HA MRSA strains tend to show significantly higher resistance to most of the non-beta lactam antibiotics. Clindamycin, Erythromycin and Ciprofloxacin show marked differences in resistance, often useful in distinguishing CA MRSA from HA-MRSA. Both types remain susceptible to Vancomycin, Teicoplanin and Linezolid, making these drugs effective treatment options. Statistical analysis was found to be significant according to the study by Preeja et al.12

Most of the MRSA strains are mediated by mecA gene, rarely mecC gene also mediates methicillin-resistance and will be phenotypically characterised by cefoxitin resistance and oxacillin susceptible.

The mecA gene encodes PBP2a, a modified penicillin-binding protein with low affinity for β-lactam antibiotics, rendering these drugs largely ineffective and resulting in broad-spectrum resistance. Our study showed 97% mecA gene and 1.5% mecC gene, while both the genes were detected in one MRSA isolate. These findings were similar to a study by Ali et al. from Pakistan, where mecA and mecC were only 54% and 3%, respectively. S. aureus mecA and mecC gene co-occurrence may occur; therefore, regular molecular monitoring and specialized antibiotic stewardship are necessary.19

PVL gene-positive Staphylococcus aureus strains are widely distributed and frequently associated with multidrug-resistance (MDR) infections in hospitals and communities. A study in Mumbai showed that most of the MRSA isolates around 54% were PVL-positive and were associated with high incidence CA-MRSA. In our study PVL gene was confirmed in 63.6% of MRSA strains and they were associated with the 83.4% of CA-MRSA. and were consistent with the above study.20 This highlights the high frequency of PVL-positive MRSA isolates, underscoring the need for effective monitoring, molecular diagnostics, and antibiotic stewardship to prevent their spread.

Biofilm-producing genes, including icaA, icaB, icaC, and icaD, were more prevalent among Staphylococcus aureus isolates. These genes are strongly associated with biofilm formation and prolonged infections. The presence of either icaA or icaD was essential for biofilm formation. In our study, nearly 123 isolates (65%) of MRSA were biofilm producers by Congo red agar method and were further confirmed genotypically. Biofilm producing intercellular adhesion genes icaA, and icaD were n = 23 (19%), and both icaB, icaC, were not detected in of the above isolates.

Another study showed, among the 68% of biofilm producing MRSA strains, 41% icaA and 31% icaB were detected, emphasizing the clinical problem faced by biofilm-forming, multidrug-resistant infections, which was statistically significant.21

The diversity and frequency of erm genes, which underlie antibiotic resistance to macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB), is also an important insight into S. aureus, increasing the caution and the likelihood of treatment failure on their use. Mahesh et al., in his study found that 29.3% inducible clindamycin resistant MRSA isolates were negative for the ermA gene differing from our study, where 3% of ermA gene found in 54.7% of the Inducible Clindamycin resistant MRSA isolates.22

Staphylococcus resistance profiles represent an important and constant threat to public healthcare worldwide. The present study highlights the alarming prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Staphylococcus aureus strains harboring key virulence factors. The coexistence of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes underscores the pathogenic potential of these isolates and poses a significant challenge to their clinical management. Our findings emphasize the urgent need for routine surveillance, molecular characterization, and stringent antibiotic stewardship programs to monitor and control the spread of MDR S. aureus. Future investigations should focus on the genetic mechanisms underlying resistance and virulence, as well as alternative therapeutic approaches, such as phage therapy or anti-virulence agents, to combat these formidable pathogens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the management and administration of Panimalar Medical College Hospital & Research Institute, Poonamallee, Chennai, India, for providing the necessary facilities and support to carry out this research. The authors are also thankful to the technical staff of the Department of Microbiology for their valuable assistance with laboratory procedures and data collection.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Institutional Human Ethics Committee, Panimalar Medical College Hospital and Research Institute, Poonamallee, Chennai, India. The ethical guidelines outlined by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) were strictly followed throughout the study.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrolling in the study.

- Miller D, Diaz MG, Perez EM, et al. Prevalence of community acquired methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus among ocular MRSA isolates. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34(5):E23-E24.

Crossref - Chambers HF. The changing epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus? Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7(2):178-182.

Crossref - Hattab S, Ma AH, Tariq Z, et al. Rapid Phenotypic and Genotypic Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Approaches for Use in the Clinical Laboratory. Antibiotics (Basel). 2024;13(8):786.

Crossref - Valle DL Jr, Paclibare PAP, Cabrera EC, Rivera WL. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from a tertiary hospital in the Philippines. Trop Med Health. 2016;44:3.

Crossref - Moghadam SO, Yaghooti MM, Pourramezan N, Pourmand MR. Molecular characterization and antimicrobial susceptibility of community acquired MRSA isolated from healthcare workers, Tehran, Iran. Microb Pathog. 2017;107:409-412.

Crossref - Shallcross LJ, Fragaszy E, Johnson AM, Hayward AC. The role of the Panton Valentine leukocidin toxin in staphylococcal disease: a systematic review and meta analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):43-54.

Crossref - Otter JA, French GL. Molecular epidemiology of community associated methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(4):227-239.

Crossref - Mesrati I, Saןdani M, Ennigrou S, Zouari B, Ben Redjeb S. Clinical isolates of Panton Valentine leucocidin and g-haemolysin-producing Staphylococcus aureus: prevalence and association with clinical infections. J Hosp Infect. 2010;75(3):265-268.

- CLSI.Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 34th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2024. https://www.darvashco.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/CLSI-2024_compressed-1.pdf

- Adhikari P, Basyal D, Rai J, et al. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and multidrug resistance of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from clinical samples at a tertiary care teaching hospital: an observational, cross sectional study from Nepal. BMJ Open. 2023;13(5):e067384.

Crossref - Idrees MM, Saeed K, Shahid MA, et al. Prevalence of mecA- and mecC-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in clinical specimens, Punjab, Pakistan. Biomedicines. 2023;11(3):878.

Crossref - Preeja PP, Kumar SH, Shetty V. Prevalence and characterization of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus from community and hospital associated infections: a tertiary care center study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(2):197.

Crossref - Ibrahim RA, Wang S, Gebreyes WA, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profile of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from patients, healthcare workers, and the environment in a tertiary hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2024;19(8):e0308615.

Crossref - Saleem M, Ahmad I, Salem AM, et al. Molecular and genetic analysis of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2025;398(6):7559-7569.

Crossref - Thati V, Shivannavar CT, Gaddad SM. Vancomycin resistance among methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from intensive care units of tertiary care hospitals in Hyderabad. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134(5):704-708.

Crossref - Lohan K, Sangwan J, Mane P, Lathwal S. Prevalence pattern of MRSA from a rural medical college of north India: a cause of concern. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(2):752-757.

Crossref - AMR Surveillance Network, Indian Council of Medical Research, 2022. https://www.icmr.gov.in/icmrobject/custom_data/pdf/resource-guidelines/AMRSN_Annual_Report_2022.pdf

- Raveendran SR, Rajesh M, Anusuya P. Prevalence of MRSA isolated from diabetic foot ulcer in tertiary care centre. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2017;16(11):43-46.

Crossref - Khan A, Ali A, Tharmalingam N, Mylonakis E, Zahra R. First report of mecC gene in clinical methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus from a tertiary care hospital Islamabad, Pakistan. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(10):1501-1507.

Crossref - D’Souza N, Rodrigues C, Mehta A. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with emergence of epidemic clones (ST) 22 and ST 772 in Mumbai, India. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(5):1806-1811.

Crossref - Malik N, Bisht D, Aggarwal J, Rawat A. Distribution of icaA and icaB genes in biofilm producing methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Asian J Pharm Res Health Care. 2022;14(1):21-24.

Crossref - Mahesh S, Kalyan R, Gupta P, Verma S, Venkatesh V, Triphati P. mecA and ermA gene discrepancy from their phenotypic profile in Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2022;12(1):6-11.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.