ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP), listed in the WHO 2024 priority, hydrolyzes β-lactam antibiotics, especially carbapenems, posing a significant challenge. Carbapenems are the last resort antibiotics for severe Gram-negative infections and are associated with increased mortality in ICUs and IPDs. This cross-sectional study at a tertiary hospital (April 2023-December 2024) included 375 multidrug-resistant (MDR) K. pneumoniae isolates with ertapenem MIC ≥8 µg/mL. Carbapenemase genes were detected via conventional PCR. Bivariate analysis examined clinical correlations, while MIC50/90 assessed resistance. The most common carbapenemase genes were blaNDM (48.26%) and blaOXA-48 (37.86%), followed by blaKPC (13.6%). Co-occurrence of genes was also reported. Twelve of seventeen clinical variables were significantly associated with gene presence (p < 0.05). Ertapenem, imipenem, and meropenem had MIC50/90 ≥8 µg/mL, indicating high resistance. Tigecycline showed better sensitivity, with MIC50/90 of 0.5/2 µg/mL (blaNDM) and 2/2 µg/mL (blaOXA-48). Fosfomycin MIC90 in blaOXA-48 isolates ranged up to 256 µg/mL. The study highlights high blaNDM and blaOXA-48 prevalence, their clinical associations, and limited therapeutic options. Tigecycline remains most effective in vitro, but pharmacokinetic concerns exist. These findings emphasize the need for antimicrobial stewardship and molecular surveillance.

Carbapenemases, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Intensive Care Unit, Multidrug-resistant

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a Gram-negative, opportunistic pathogen commonly involved in both community- and hospital-acquired infections, including pneumonia, urinary tract infections (UTIs), bloodstream infections, and wound infections.1 Its capacity to acquire resistance genes, survival on hospital surfaces, and dissemination through plasmid transfer makes it a significant healthcare challenge. The World Health Organization (WHO) has listed carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP) as a “critical priority pathogen”, highlighting the urgent need for global surveillance and new treatment options.2-4

Carbapenems such as imipenem, meropenem, and ertapenem are considered last-resort antibiotics for treating multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales, primarily strains that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs).2,4 The effectiveness of carbapenems has also been significantly reduced due to the emergence of carbapenemase-producing organisms. These enzymes, such as K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), OXA-48-like oxacillinases, IMP (Imipenemases), VIM (Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase), and NDM (New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase), hydrolyze carbapenems and other β-lactam antibiotics. The spread of these resistance genes through plasmids has accelerated their global dissemination.5,6

CRKP prevalence varies significantly by region. In India, blaNDM and blaOXA-48 are most common, with hospital studies showing rates of 45%-65%.5-7 China reports a high prevalence of KPC and NDM, with rates of up to 60%-70% in tertiary centers.8,9 In Europe, prevalence exceeds 40% in countries such as Greece and Italy, while it stays below 5% in northern regions.2,10-12 In contrast, the United States has a lower prevalence (<10%), with KPC remaining the most common carbapenemase.13 This worldwide variation underscores the impact of regional antibiotic use, infection-control strategies, and genetic exchange processes on the epidemiology of CRKP.

The lack of rapid, accurate diagnostic tests for detecting carbapenemases makes treatment more difficult, often leading to delays in administering effective therapies. As a result, clinicians are usually forced to rely on last-resort antibiotics like colistin, fosfomycin, or tigecycline drugs that can be toxic or have inconsistent success rates, with growing reports of resistance.8,9 These treatment challenges increase patient morbidity and mortality and promote the development of pan-drug-resistant bacteria.14,15

In this context, thorough hospital-based surveillance is essential. This study—carried out at a single tertiary-care centre—utilized various baseline clinical and microbiological data, such as infection type, comorbidities, ICU admissions, bacterial co-infections, and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC50/90) values, to characterize carbapenemase-producing multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (MDR-CRKP). The primary objective is to determine the prevalence and genetic diversity of carbapenemase genes among MDR-CRKP strains isolated from intensive care units and inpatient environments. Since the analysis is based on data from a single centre, its findings might not be entirely applicable to other hospitals or regions. Nonetheless, they offer valuable local insights that can support antimicrobial stewardship and infection-control efforts while also enhancing overall understanding of CRKP epidemiology.

This cross-sectional study was conducted from April 2023 to December 2024. It included all clinical samples received from various inpatient departments (ICU) and intensive care units (ICUs) within the Department of Microbiology at the Maharishi Markandeshwar Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Mullana, India. Informed consent from the patients was collected at the time of specimen collection and ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee vide letter number MMIMSR/IEC/2427.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Samples from ICUs and various IPDs (e.g., Medicine, Surgery, Neurosurgery, Paediatric, Respiratory Medicine, Urology, Obstetrics and Gynaecology) were included in the study. In contrast, samples from Outpatient departments (OPDs) and repeated organisms from the same patient were excluded from the study.

Sample processing

All clinical specimens were initially examined by direct microscopy using Gram staining or wet-mount techniques to identify inflammatory cells and microorganisms.

Samples, except blood, were inoculated on routine media, such as Blood Agar and MacConkey Agar, and then incubated at 37 °C for 24-48 hours under aerobic conditions.

For blood cultures, approximately 5-7 mL of venous blood was collected under sterile conditions and placed into BACTEC culture bottles, which were then loaded into the BD BACTEC FX40 automated system for continuous monitoring over five days. Bottles that indicated a positive result were Gram-stained and subcultured onto Blood and MacConkey agar plates, then incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. Blood culture bottles that showed no signal after five days were deemed culture-negative.

Identification of bacteria and antibiotic sensitivity testing

A bacterial suspension was prepared by emulsifying well-isolated colonies in 3 mL sterile saline in a 12 × 75 mm polystyrene test tube. Using the Densichek Plus turbidity meter (BioMerieux, India), turbidity was adjusted to 0.5 McFarland. The interval between preparing the bacterial inoculum and loading the VITEK cards did not exceed 30 minutes.

Bacteria were identified by the VITEK-2 Compact System utilizing Gram-negative (GN) identification cards. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) was performed using the N405 and N235 AST cards, following the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines and the manufacturer’s protocols.16 The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of an antibiotic that may inhibit 50% and 90% of bacterial isolates were calculated as MIC50 and MIC90.17

Categorization of multidrug-resistant isolates

MDR organisms are resistant to at least one agent in at least three antimicrobial categories.18

Carbapenemase screening

An isolate showing an MIC ≥8 µg/mL of ertapenem was collected.15

DNA extraction

All MDR isolates showing MIC ≥8 µg/mL of ertapenem were collected, and DNA extraction was performed using Geno Sen’s Genomic DNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was stored

at -20 °C.

Polymerase chain reaction conditions

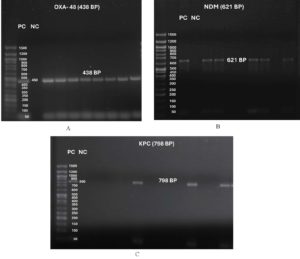

Conventional PCR was used to identify: blaKPC, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaIMP, and blaOXA-48, following previously published techniques reported by Booq et al.19 (Table 1). The PCR products were evaluated through electrophoresis at 80 V for 45 minutes in a 2% agarose gel, with bands visualized using a UV transilluminator.

Statistical analysis

A forest plot displaying odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals and significance, along with a scatter plot of MIC50 and MIC90, was created in R version 4.4.3.

Of 612 Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates, 375 were MDR (Table 1). No blaVIM and blaIMP genes were detected in the current study. Of the 375 CRKP isolates, 159 (42.4) were from males, and 216 (57.6) were from females.

Year-wise distribution

Between 2022 and 2024, the most prevalent gene was blaNDM, followed by blaOXA-48 and blaOXA-48 + blaNDM. No relation was found among these parameters using bivariate analysis.

Type of infection

Non-UTI cases included bloodstream, lower respiratory tract, and wound infections. A significant association was observed between UTI cases and the blaNDM gene (p < 0.05). While no association was established among non-UTI cases due to the small sample size.

ICU admissions

Among 138 patients, 72 patients had an ICU stay of more than 7 days, followed by 66 patients with a stay of less than 5 days. A significant association was observed between ICU admissions and the presence of blaOXA-48 and blaOXA-48 + blaNDM.

Comorbidities

A significant association was established between diabetes mellitus and blaNDM. The association between age and other genes was found to be non-significant. A significant association was seen between other co-morbid conditions and blaNDM and blaOXA-48.

Bacterial co-infection

A significant association was observed between blaKPC, blaNDM, and blaOXA-48, as well as between blaOXA-48 and blaNDM.

MIC50 and MIC90

Most antibiotics have an MIC90 of CRKP equal to the MIC50, and the resistance rate was high among β-lactam combinations, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, etc. Tigecycline was the most sensitive drug after Fosfomycin.

K. pneumoniae causes serious community-acquired and healthcare-associated infections. Carbapenems are a last-resort antibiotic for treating severe Gram-negative bacterial infections, and carbapenem resistance increases patient mortality and morbidity.4,20,21

Due to its ability to survive on medical equipment and colonize patients and hospital staff asymptomatically in hospitals, K. pneumoniae frequently causes outbreaks of epidemic proportions that are easily transmitted between wards. Consequently, plasmids harboring genes encoding carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzymes can be readily transmitted among various strains. Furthermore, a single plasmid may contain multiple resistance determinants, thereby facilitating the emergence of multidrug-resistant K. pneumoniae strains that contribute to highly challenging intrahospital epidemics.22 The present study assessed 375 MDR K. pneumoniae isolates with an ertapenem MIC≥8 µg/mL. The majority of samples collected in the current study were urine (61.33%). We investigated the genes responsible for carbapenem resistance in patients with and without urinary tract infections (UTIs), and 230 (61.3%) of the carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates were derived from urine samples. Similar results were also reported in a study conducted by Pruss et al.21 (Tables 1-3).

Table (1):

Primers for identification of genes responsible for Carbapenem-resistance

| No. | Gene | Nucleotide Sequence | Amplicon size |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | blaKPC | KPC F-CGTCTAGTTCTGCTGTCTTG | 798 |

| KPC R-CTTGTCATCCTTGTTAGGCG | |||

| 2. | blaNDM | NDM F-GGTTTGGCGATCTGGTTTTC | 621 |

| NDM R-CGGAATGGCTCATCACGATC | |||

| 3. | blaIMP | IMP F-GGAATAGAGTGGCTTAAYTCTC | 232 |

| IMP R-GGTTTAAYAAAACAACCACC | |||

| 4. | blaVIM | VIM F-GATGGTGTTTGGTCGCATA | 390 |

| VIM R-CGAATGCGCAGCACCAG | |||

| 5. | blaOXA-48 | OXA-48 F-GCGTGGTTAAGGATGAACAC | 438 |

| OXA-48 R-CATCAAGTTCAACCCAACCG |

Table (2):

Culture positivity rate and distribution of microbial isolates among various clinical samples

| Total No. of Samples Processed | No Growth | Gram-Positive | With Growth (n = 4077) (40.2%) | Candida spp. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative (n = 2981) (29.4%) | ||||||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Klebsiella oxytoca | Other Gram-negative isolates | ||||

| 10132 | 6055 | 1050 | 612 | 150 | 2219 | 46 |

| (59.8%) | (10.4%) | (6%) | (1.5%) | (21.9%) | (0.5%) | |

Table (3):

Distribution of Klebsiella pneumoniae (multidrug-resistant and carbapenem-resistant) among various clinical specimens (n = 375)

No. |

Type of Sample |

No. of sample (%) |

|---|---|---|

1. |

Urine |

230 (61.3%) |

2. |

Respiratory secretions |

40 (10.7%) |

3. |

Pus |

37 (9.9%) |

4. |

Wound Swabs |

35 (9.3%) |

5. |

Blood and sterile fluids |

33 (8.8%) |

Various studies recommend gene transfer as a potential trait among enterobacterales, thereby increasing antimicrobial resistance.23,24 Plasmid-mediated horizontal gene transfer is a key factor in the ongoing evolution of bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR).25 We examined the presence of carbapenemase and its association with its occurrence (both in confirmed coinfections and carriage). In the current study, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Citrobacter freundii, Acinetobacter baumannii complex, Enterobacter cloacae complex, Proteus spp., and Providencia spp. were the most commonly found organisms. Co-occurrences of bacteria were also observed in 145 cases. The study did not include Gram-positive bacteria or fungi isolated during microbiological sampling (Table 3).

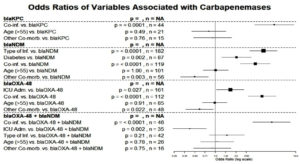

According to the Ambler classification, K. pneumoniae mainly contains three primary types of carbapenemases: class D, also called oxacillinase-hydrolysing (OXA); class B, sometimes called metallo-beta-lactamases (MBLs); and class A, also called serine β-lactamases. The blaKPC gene encodes K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), a crucial enzyme that contributed to the worldwide spread of CRKP. Carbapenemases can render resistance to all beta-lactam antibiotics, including carbapenems, monobactams, and extended-spectrum cephalosporins. Carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae was also associated with the other carbapenemases, including OXA-48, VIM, IMP, and NDM.1,26 Among 375 MDR K. pneumoniae, the majority of the genes responsible for carbapenem resistance were blaNDM (48.26%), blaOXA-48 (37.86%), and blaKPC (13.6%). In some bacterial isolates, co-occurrence of genes was also observed, which included blaOXA-48 + blaNDM (16.26%), blaKPC + blaNDM (0.53%), and blaKPC + blaOXA-48 (1.06%). In the current study, bivariate analysis of baseline characteristics was carried out to assess the association of different variables with the carbapenem gene, and a Forest Plot was created to establish relationships among variables, showing odds ratios along with their 95% confidence intervals and significance associated with various variables (p is significant at p < 0.05). Twelve out of 17 correlations were significant, demonstrating substantial effects (OR = 7.27 for Co-inf. vs. blaKPC) and protective effects (OR = 0.42 for ICU Admission vs. blaOXA-48 + blaNDM). Mainly, age (>55) and a few other co-morbidities displayed weaker or no relationships. Larger squares (e.g., n = 182, n = 119) indicate more robust significant findings (Figures 1 & 2 and Table 4).

Table (4):

Baseline Characteristics and their association with genes conferring Carbapenem-resistance

| Variables | All (n = 375) (%) | blaKPC (n = 51) (%) | blaNDM (n = 181) (%) | blaOXA-48 (n = 142) (%) | blaOXA-48 + blaNDM (n = 61) (%) | blaKPC + blaNDM (n = 2) (%) | blaKPC + blaOXA-48 (n = 4) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year-Wise Distribution | |||||||

| 2022 | 112 (29.8) | 12 (23.5) | 48 (26.5) | 38 (26.7) | 17 (27.8) | 0 | 1 (25) |

| 2023 | 125 (33.3) | 16 (31.3) | 62 (34.2) | 47 (33) | 21 (34.4) | 1 (50) | 1 (25) |

| 2024 | 138 (36.8) | 23 (45) | 71 (39.2) | 57 (40.1) | 23 (37.7) | 1 (50) | 2 (50) |

| Type of Infection | |||||||

| UTI | 230 (61.3) | 34 (66.6) | 138 (76.2) | 88 (61.9) | 42 (68.8) | 2 (100) | 3 (75) |

| Non-UTI | 145 (38.6) | 17 (33.3) | 43 (23.7) | 54 (38) | 19 (31.1) | 0 | 1 (25) |

| ICU Admission Comorbidities | 275 (73.3) | 38 (74.5) | 148 (81.7) | 124 (87.3) | 35 (57.3) | 1 (50) | 2 (50) |

| Diabetes | 115 (30.6) | 18 (35.2) | 66 (36.4) | 54 (38) | 19 (31.1) | 2 (100) | 1 (25) |

| Mellitus | |||||||

| Age (>55) | 155 (41.3) | 19 (37.2) | 75 (41.4) | 57 (40.1) | 26 (42.6) | 0 | 2 (50) |

| Other Co-morbid Conditions* | 105 (28) | 14 (27.4) | 40 (22) | 31 (21.8) | 16 (26.2) | 0 | 1 (25) |

| Bacterial co-infection# | 145 (38.6) | 41 (80.3) | 119 (65.7) | 112 (78.8) | 46 (75.4) | 1 (50) | 2 (50) |

Other Co-morbid Conditions*- Hypertension, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and malignant conditions Bacterial co-infection#– Co-infection with Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii complex, Citrobacter freundii, Proteus spp., Providencia spp., and Enterobacter cloacae complex

Figure 1. Forest plot showing odds ratios of variables associated with carbapenemases with their 95% confidence intervals and significance

Figure 2. Gel electrophoresis image showing DNA ladder (50 bp) along with Positive and Negative Controls and test strains: (A) blaOXA-48 (438 bp), (B) blaNDM (621 bp) and (C) blaKPC (798 bp)

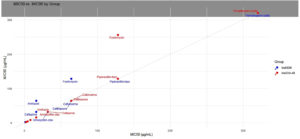

Misuse of antibiotics, which has gone unchecked for many years, has led to one of the most significant global health risks. The development of antibiotic resistance in organisms such as CRKP has become an obstacle to physicians treating severe infections. The strongest indication of increased evolutionary rates in these infections is their response, which enables them to evade antibiotic action and demonstrates their exceptional adaptation. Both colistin and tigecycline exhibit good in vitro activity against CRKP; however, resistance during therapy remains a serious health concern.21 Multidrug-resistant and extremely drug-resistant strains arise from their immense genetic potential.22 The MDR strains were sensitive to tigecycline but highly resistant to cephalosporins, carbapenems, aminoglycosides, β-lactam combinations, and fluoroquinolones. A scatter plot of MIC50 versus MIC90 was generated. The points (32, 32), (64, 64), (128, 128), and so on lie on the 1:1 line, indicating consistent resistance (e.g., to amoxicillin-clavulanate and ceftriaxone). Tigecycline values were (1, 2) for blaNDM and (2, 2) for blaOXA-48, both of which are near or on the line, indicating minimal variation. Fosfomycin at (64, 128) for blaNDM and (128, 256) for blaOXA-48 is located above the line, indicating a greater spread of resistance, notably in blaOXA-48. The dotted grey line extends diagonally from (0, 0) to the top-right, intersecting at MIC50 = MIC90 (Figure 3 and Table 5).

Table (5):

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing results of carbapenemase-producing MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae strains (ertapenem MIC ≥8 µg/mL) (n = 375)

| Antimicrobial agent | All MDR & carbapenemase- producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 375) | blaNDM producers (n = 181) | blaOXA-48 producers (n = 142) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC calling Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | %R | MIC50 | MIC90 | %R | MIC50 | MIC90 | %R | |

| Amoxycillin- clavulanic acid | ≤4/2 – ≥32/16 | ≥32/16 | ≥32/16 | 99.7 | ≥32/16 | ≥32/16 | 100 | ≥32/16 | ≥32/16 | 100 |

| Piperacillin- tazobactam | ≤4/4 – ≥128/4 | ≥128/4 | ≥128/4 | 98.6 | ≥128/4 | ≥128/4 | 100 | ≥128/4 | ≥128/4 | 100 |

| Ceftriaxone | ≤0.25 – ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 99.7 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 100 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 100 |

| Cefuroxime | ≤1 – ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 100 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 100 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 100 |

| Cefepime | ≤0.12 – ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | 98.4 | ≥16 | ≥32 | 99.5 | ≥32 | ≥32 | 100 |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.06 – ≥4 | ≥4 | ≥4 | 99.7 | ≥4 | ≥4 | 100 | ≥4 | ≥4 | 100 |

| Amikacin | ≤1 – ≥64 | ≥16 | ≥32 | 93.8 | ≥16 | ≥64 | 95 | ≥32 | ≥32 | 95 |

| Gentamicin | ≤1 – ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 98.1 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 99.5 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 99.5 |

| Imipenem | ≤0.25 – ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 100 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 100 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 100 |

| Meropenem | ≤0.25 – ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 100 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 100 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 100 |

| Fosfomycin | ≤16 – ≥256 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 91.4 | ≥64 | ≥128 | 92.8 | ≥128 | ≥256 | 96.5 |

| Trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole | ≤20 (1/19)- ≥320 (16/304) | ≥320 | ≥320 | 96.8 | ≥320 | ≥320 | 98.9 | ≥320 | ≥320 | 100 |

| Tigecycline | ≤0.5 – ≥8 | 0.5 | 2 | 51.4 | ≥1 | ≥2 | 69.8 | ≥2 | ≥2 | 80.7 |

%R = Resistant Percentage, MIC50 and MIC90: MIC of an antibiotic that may inhibit 50% and 90% of bacterial isolates

Figure 3. Scatter Plot of MIC50 versus MIC90 illustrating the relationship between MIC50 and MIC90 for each group of antibiotics, demonstrating the variation in resistance levels

The current study shows higher resistance to antibiotics such as cephalosporins, β-lactam combinations, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones, thereby limiting their effectiveness. To enhance clinical outcomes, it is crucial to develop new therapies and dosing strategies without delay. Despite the intricate and varied causes of urinary tract infections, the bacteria’s ability to adhere has accelerated the development of non-antibiotic alternative anti-adhesion treatments.27,28 The findings of this study further emphasize the importance of optimizing infection control measures and antibiotic stewardship practices, especially considering the prevalence of blaNDM and blaOXA-48. Recommended strategies encompass active surveillance, rapid identification of carriers, strict contact precautions, and improved environmental sanitation within intensive care units. Routine screening in regions prone to outbreaks can prevent covert transmission. It is imperative to update treatment protocols, reduce carbapenem usage, and promote the adoption of carbapenem-sparing therapies. Regular analysis of antibiograms and the integration of molecular resistance data are vital in mitigating the dissemination of resistant CRKP strains. These targeted interventions are essential within a single-center setting, where transmission dynamics and antibiotic utilization significantly influence resistance patterns.

In our study, blaNDM and blaOXA-48 were the most frequent carbapenemase genes. Co-occurrence of genes was also seen in many isolates, and the majority of bacteria harbouring multiple genes had co-infection, which may be attributed to the transfer of genetic material. Out of the seventeen relationships analysed, twelve were found to be significant. Tigecycline showed the highest sensitivity in this study; however, its therapeutic use has limitations.

Limitations

This study, being single-centric, only represents data within the region, and representativeness is relatively high. The current study had limitations, including the multiple variables in the APACHE II score and other comorbid conditions in ICU patients, which would have provided a better understanding, but were not considered due to data unavailability. Also, in the current study, various CRKP resistance mechanisms and Sequence type (ST) typing studies were not done; to fill the gap in the current study, Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) genotyping will be carried out for all CRKP strains, and whole genome sequencing will be carried out when required in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Maharishi Markandeshwar Institute of Medical Sciences and Research for their support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

RK, NK and HK conceptualized the study. RK, HK, SC and SK performed data collection and analysis. RK, HK and RB wrote the manuscript. NK, BKA and RB reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the the Institutional Ethics Committee, Maharishi Markandeshwar Institute of Medical Sciences & Research Mullana, Ambala, India, vide letter number MMIMSR/IEC/2427.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrolling in the study.

- Jafari-Sales A, Al-Khafaji NSK, Al-Dahmoshi HOM, et al. Occurrence of some common carbapenemase genes in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates collected from clinical samples in Tabriz, northwestern Iran. BMC Res Notes. 2023;16(1):311.

Crossref - Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(3):318-327.

Crossref - Kaur N, Kumar H, Bala R, et al. Prevalence of Extended Spectrum Beta-lactamase and Carbapenemase Producers in Gram Negative Bacteria causing Blood Stream Infection in Intensive Care Unit Patients. J Clin Diagn Res. 2021;15(11):DC04-DC07.

Crossref - Division AR. Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system ( GLASS) report: 2022 [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://www.who. int/publications/i/item/9789240062702/[Accessed 11 September 2025]

- Choudhury K, Dhar (Chanda) D, Bhattacharjee A: Molecular characterization of extended spectrum beta lactamases in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp from a tertiary care hospital of South Eastern Assam. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2022;40(1):135-137.

Crossref - Biswas P, Batra S, Gurha N, Maksane N. Emerging antimicrobial resistance and need for antimicrobial stewardship for ocular infections in India: A narrative review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(5):1513-1521.

Crossref - Kamalakar S, Rameshkumar MR, Jyothi TL, et al. Molecular detection of blaNDM and blaOXA-48 genes in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from a tertiary care hospital. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2024;36(7):103233.

Crossref - Jin Y, Dong C, Shao C, Wang Y, Liu Y: Molecular Epidemiology of Clonally Related Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Newborns in a Hospital in Shandong, China. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2017;10(9):e14046.

Crossref - Yan J, Pu S, Jia X, et al. Multidrug Resistance Mechanisms of Carbapenem Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains Isolated in Chongqing, China. Ann Lab Med. 2017;37(5):398-407.

Crossref - Al-Baz AA, Maarouf A, Marei A, Abdallah AL. Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance Profiles of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolated from Tertiary Care Hospital, Egypt. Egypt J Hosp Med. 2022;88(1):2883-2890.

Crossref - Tsolakidou P, Tsikrikonis G, Tsaprouni K, Souplioti M, Sxoina E. Shifting molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a regional Greek hospital: Department-specific trends and national context (2022–2024). Act Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2025;72(3):212-219.

Crossref - Guido M, Zizza A, Sedile R, Nuzzo M, Lupo LI, Grima P: Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria in Hospitalized Patients: A Five-Year Surveillance in Italy. Infect Dis Rep. 2025;7(4):76.

Crossref - Bonomo RA, Burd EM, Conly J, Limbago BM, Poirel L, Segre JA, Westblade LF: Carbapenemase-Producing Organisms: A Global Scourge. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2018;66(8):1290-1297.

Crossref - Alexander BT, Marschall J, Tibbetts RJ, Neuner EA, Dunne WM, Ritchie DJ. Treatment and clinical outcomes of urinary tract infections caused by KPC-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a retrospective cohort. Clin Ther. 2012;34(6):1314–1323.

Crossref - Kumar H, Kaur N, Kumar N, Chauhan J, Bala R, Chauhan S: Achieving pre-eminence of antimicrobial resistance among non-fermenting Gram-negative bacilli causing septicemia in intensive care units: A single center study of a tertiary care hospital. Germs. 2023;13(2):108-120.

Crossref - CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 32nd ed. CLSI supplement M100. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2022. https://clsi.org/about/news/clsi-publishesm100-performance-standards-for-antimicrobialsusceptibility-testing-32nd-edition/[Accessed 11 September 2025]

- Catania S, Bottinelli M, Fincato A, et al. Evaluation of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations for 154 Mycoplasma synoviae isolates from Italy collected during 2012-2017. PloS One. 2019;14(11):e0224903.

Crossref - Cosentino F, Viale P, Giannella M. MDR/XDR/PDR or DTR? Which definition best fits the resistance profile of Pseudomonas aeruginosa? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2023;36(6):564-571.

Crossref - Booq RY, Abutarboush MH, Alolayan MA, et al. Identification and Characterization of Plasmids and Genes from Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Makkah Province, Saudi Arabia. Antibiotics. 2022;11(11):1627.

Crossref - Spellberg B, Gilbert DN. The Future of Antibiotics and Resistance: A Tribute to a Career of Leadership by John Bartlett. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2014;59(Suppl 2):S71–S75.

Crossref - Pruss A, Kwiatkowski P, Sienkiewicz M, et al. Similarity Analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae Producing Carbapenemases Isolated from UTI and Other Infections. Antibiotics. 2023;12(7):1224.

Crossref - Khairy RMM, Mahmoud MS, Shady RR, Esmail MAM: Multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in hospital-acquired infections: Concomitant analysis of antimicrobial resistant strains. Int J Clin Pract. 2020;74(4):e13463.

Crossref - Potron A, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Derepressed transfer properties leading to the efficient spread of the plasmid encoding carbapenemase OXA-48. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(1):467-471.

Crossref - Virolle C, Goldlust K, Djermoun S, Bigot S, Lesterlin C. Plasmid Transfer by Conjugation in Gram-Negative Bacteria: From the Cellular to the Community Level. Genes. 2020;11(11):1239.

Crossref - Rozwandowicz M, Brouwer MSM, Fischer J, et al. Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73(5):1121-1137.

Crossref - Pourgholi L, Farhadinia H, Hosseindokht M, et al. Analysis of carbapenemases genes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from Tehran heart center. Iran J Microbiol. 2022;14(1):38-46.

Crossref - Wang N, Zhan M, Wang T, et al. Long Term Characteristics of Clinical Distribution and Resistance Trends of Carbapenem-Resistant and Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Klebsiella pneumoniae Infections: 2014-2022. Infect Drug Resist. 2023;16:1279-1295.

Crossref - Sarshar M, Behzadi P, Ambrosi C, Zagaglia C, Palamara AT, Scribano D. FimH and Anti-Adhesive Therapeutics: A Disarming Strategy Against Uropathogens. Antibiotics. 2020;9(7):397.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.