ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

A total of 23 sulfur-oxidizing bacterial (SOB) isolates were recovered from the rhizosphere of onion plants (Allium cepa L.), among which isolates B12 and B15 demonstrated the highest sulfur-oxidizing potential. These two isolates markedly reduced the pH of the growth medium from 8.38 to 7.01 and 7.12, respectively, even in the absence of glucose, indicating strong sulfur-oxidizing capacity. Molecular identification based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing revealed that B12 corresponds to Bacillus spizizenii strain B566 (GenBank Accession number PX437460 with 99% similarity), while B15 corresponds to Priestia aryabhattai strain B567 (GenBank Accession number PX437823 with 99% similarity). Both strains exhibited progressive sulfate accumulation with incubation time. After one week, sulfate concentrations reached 119.9 and 696.7 mg SO₄²⁻ L⁻¹ for the two strains, respectively. Additionally, both isolates were capable of synthesizing the plant growth hormone indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) at concentrations of 141.9 µg/mL for B. spizizenii and 116.6 µg/mL for P. aryabhattai when cultivated in tryptophan-enriched medium. These findings highlight the potential application of B. spizizenii and P. aryabhattai as biofertilizer candidates to enhance sulfur availability and promote plant growth in sustainable agricultural systems.

Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria, Rhizosphere, Onion (Allium cepa), Bacillus spizizenii, Priestia aryabhattai, Biofertilizer

In crop production, Sulfur is recognized as the fourth essential macronutrient for crop production, following nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium.1 Its importance is prominent from sharing in the structure of cysteine and methionine amino acids, thiamine and biotin vitamins beside coenzyme A and antioxidants such as lipoic acid.2,3 Stated that sulfate (SO42-) was found to be the most sulfur form a plant could uptake to share in metabolic pathways and formation of specific compounds. That is why biological sulfur transformation is crucial in global sulfur cycle for plant benefit, specifically by soil microbiota, such as in SO42- formation through hydrogen sulfide oxidation.4

One of the major soil microbiota involved in SO42- formation are sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (SOB). Besides converting reduced sulfur compounds into sulfate, SOB also generate acidity as a byproduct, which helps solubilize nutrients and thus enhance soil fertility for plant growth.5 The sulfide ion oxidation is done by SOB through their sulfide oxidase enzyme.6

The chemolithoautotrophic SOB are pervasive in various environments including geosphere and hydrosphere.7 Sulfur aerobic oxidation by SOB is self-beneficial to gain energy beside its role in SO4²– and hydrogen ion formation as shown in Eq. 18:

S0 + H2O + 1.5O2 → SO42- + 2H+,

ΔG0 = -587 kJ/mol reaction

…(1)

On the other hand, the thiosulfate (S2O3²–), as another form of sulfur compound, is stable in aerated aqueous abiotic medium specifically in pH 10. Thiosulfate can be removed by biological oxidation from its environment by SOB depending on available oxidizing agent present and considered as an important source of energy,9 and clarified in Eq. 2 :

S2O32- + H2O + 2O2 → 2SO42- + 2H+,

ΔG0 = – 818.3 kJ/mol reaction

…(2)

It is noteworthy that sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (SOBs) mitigate the toxicity of reduced sulfur compounds, including H2S and DMS, by converting them into less harmful forms during microbial oxidation.10

This study aims to isolate and characterize potential sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (SOB) from the onion (Allium cepa L.) rhizosphere and to evaluate their potential as biofertilizers for enhancing sulfur availability and promoting soil fertility.

Study sites, sampling and Isolation

Isolation of Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacteria (SOB) was performed using rhizosphere soil samples collected in triplicates from three major onion (Allium cepa L.) cultivation sites in Assiut Governorate. The three samples from each site were taken at considerable distances following a randomized protocol, yielding nine independent sampling points to ensure spatial variation.

The Starkey medium broth used for SOB isolation consisted of (per liter distilled water): 3.0 g KH2PO4 (22 mM), 0.2 g MgSO4·7H‚ O (0.8 mM), 0.2 g CaCl‚ ·2H2O (1.8 mM), 0.5 g (NH4)2SO4 (3.8 mM), and traces of FeSO4, adjusted to pH 8.0. Bromocresol purple was added as a pH indicator.11 The medium was sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 20 min under the standard cycle for media preparation. Elemental sulfur at 10 g per liter was added to the medium and half-an-hour steam sterilized for three consecutive days.

Ten grams of each soil sample was added to 90 ml of broth dispensed in sterilized conical flasks under aseptic conditions. The flasks were incubated at 32 °C

for 25 days. Color change from purple to yellow indicated the growth of SOB in the medium.12 SOB isolates were transferred to fresh Starkey broth from which they were streaked on thiosulfate agar medium thrice at fortnightly intervals for further purification and the purified colonies.13 The single colonies were picked and preserved on thiosulfate slants and finally those SOBs pure cultures were labeled and used for characterization and further studies.

SOB growth behavior in presence or absence of glucose

To evaluate the behavior of SOBs isolates in the presence or absence of glucose, their pure cultures were screened using a modified thiosulfate broth medium.14 The medium composed of (g/L): 5.0 g sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3), 0.1 g dipotassium phosphate (K2HPO4), 0.2 g sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), 0.1 g ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), and 5.0 g glucose (present or omitted depending on the treatment), adjusted to pH 8.0.

Fifty milliliters of the prepared broth were dispensed into sterile conical flasks, and each isolate was aseptically inoculated into the medium. The cultures were incubated in a shaker incubator at 120 rpm and a temperature of 30-32 °C for 14 days.

Microbial growth in thiosulfate broth was assessed by measuring turbidity at 600 nm, according to Lindqvist.15 The pH value and electrical conductivity (EC) of the culture medium were measured on days 7 and 14 using a pH and EC meters, following the protocol.16 For estimating ionic strength (I), an empirical model based on electric conductivity for EC > 592.6 µS·cm-1,17

as follows:

I = [10.647 × 10-6 × EC] + [26.373 × 10-4]

Sulfate ion (SO42-) concentration, indicating sulfur oxidation, was determined spectrophotometrically. A 1:1 volume of 10% (w/v) barium chloride solution was added to the supernatant, and the resulting turbidity from barium sulfate formation was measured at 450 nm.18 Potassium sulfate (K2SO4) was used to generate a standard calibration curve for sulfate quantification.19

SOB growth potential as autotrophs or mixotrophs

The most effective SOB isolates that succeeded in lowering pH value of growth medium were chosen to test their autotrophic or mixotrophic behavior. Chosen SOBs were cultivated in thiosulfate broth medium either in presence or absence of glucose supplementation. Throughout the experiment, pH, electrical conductivity (EC), sulfate concentration and OD were measured to assess the physiological and biochemical responses of the isolates.

Plant growth-promoting characteristics of chosen SOBs

The most potent isolates were cultivated in nutrient broth enriched with 0.1 g/L of tryptophan and incubated at 33 ± 2 °C for a period of three days. The production of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) was quantified using the colorimetric method.20 Total gibberellin (GA) content was estimated according to the procedure of Udagawa and Kinoshita.21 Furthermore, bacterial population density was determined by calculating the total viable counts and expressed as log CFU/mL, following the methodology.22

Molecular identification of the two most effective bacterial isolates

The two most efficient sulfur-oxidizing bacterial isolates were cultivated in sterile test tubes containing 10 mL of nutrient broth23 and incubated at 28 °C for 48 hours. Genomic DNA was extracted at the Molecular Biology Research Unit, Assiut University, using the Patho-Gene-Spin DNA/RNA Extraction Kit (Intron Biotechnology, Korea). The extracted DNA samples were submitted to SolGent Co., Ltd. (Daejeon, South Korea) for amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. PCR amplification was carried out using universal bacterial primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). The amplified PCR products (amplicons) were verified by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel using a 100 bp DNA ladder. Bidirectional sequencing was conducted using the same primer pair and the Sanger method with dideoxynucleotide (ddNTP) incorporation.24

The obtained sequences were analyzed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) to determine phylogenetic affiliation. Multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic tree construction were performed using MegAlign software (DNASTAR, version 5.05).

Alignments and phylogenetic analyses

Two phylogenetic trees were constructed and visualized using Geneious Prime (version 2022.2.2; https://www.geneious.com). Bootstrap support values for both Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Maximum Parsimony (MP) analyses were indicated above and below the respective nodes. Final formatting was performed in Microsoft PowerPoint (2010), and figures were exported as high-resolution Tagged Image File Format (TIFF) files.

Scanning electron microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to examine the surface of the agricultural sulfur granules used in the bacterial isolation experiment. The aim was to investigate the presence of naturally occurring sulfur-oxidizing bacteria colonizing the sulfur surface. Granules were fixed in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C for 6 hours, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 hours, and then dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (50%-100%). Samples were dried using a Polaron apparatus with Freon 13, sputter-coated with gold using a Technics Hummer (JEOL-1100E), and examined under a JEOL JSM-5400LV scanning electron microscope.25

Statistical analysis

Experimental analysis was carried out in triplicates. Result data obtained in triplicates were statistically evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at a significance level of 5%26 using CoHort software (Costat model 6.311). DMRT was selected as it is widely applied in agricultural and microbial studies and provides an appropriate balance between sensitivity and control of Type I error in multiple comparisons. Standard errors, graphic presentations, and Pearson’s correlation coefficients were all calculated using Microsoft Excel (Office 2010).

Isolation of sulfur oxidizing bacteria

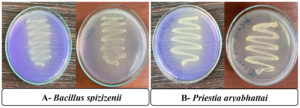

Out of soil samples collected from three sites, only 23 bacterial isolates showed positive results in oxidizing elemental sulfur (SOB) indicated by apparent change in medium color from purple to pale yellow, as shown in Figure 1. Those 23 SOBs isolates were subsequently evaluated for their sulfur-oxidizing potential in modified thiosulfate broth.

Figure 1. Bromocresol purple test for pH on thiosulfate media for (A) Bacillus spizizenii and (B) Priestia aryabhattai

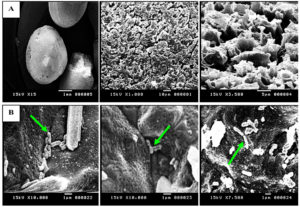

Morphological Characterization of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (SOB) and sulfur substrates by Scanning Electron Microscopy

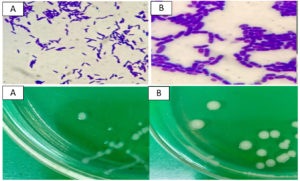

To assess the interaction between sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (SOB) and sulfur substrates, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was performed on samples from cultures grown with and without sulfur supplementation. SEM analysis revealed a pronounced attachment of SOB to the surfaces of sulfur granules developed in sulfur-enriched broth (Figure 2A). In contrast, control cultures lacking sulfur exhibited minimal or no bacterial attachment to solid substrates (Figure 2B). The cells observed on the granules were rod-shaped and morphologically consistent with those of the SOB strains isolated in pure cultures as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) (A) no SOB attached to sulfur granules, (B) rod shaped SOB cells attached to sulfur granules

Figure 3. Morphological characteristics of cells and colonies of (A) Bacillus spizizenii and (B) Priestia aryabhattai

Change in pH value and sulfur-oxidizing potential of SOB isolates

The thiosulfate-based medium without glucose amendment demonstrated distinct patterns in SOB responses through two weeks of incubation (Table 1). Generally, decrease in pH values were observed during the first week. Notably, isolates B12 and B15 exhibited the greatest reductions in pH, where the initial value of 8.38 decreased by ≈15%-16% down to 7.01 and 7.06, respectively.

Table (1):

23 bacterial isolates tested for variations in final pH values and sulfur oxidation (sulfate formation) when grown on modified thiosulfate broth medium for 2 weeks in absence of glucose

| pH | SO42- | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -G W1 | -G W2 | -G W1 | -G W2 | |

| MEAN ± SE | MEAN ± SE | MEAN ± SE | MEAN ± SE | |

| Control | 8.38 ± 0.01b | 8.47 ± 0.01i | 25.280 ± 0.003u | 15.282 ± 0.006x |

| B1 | 8.33 ± 0.00de | 8.87 ± 0.01a | 35.290 ± 0.006s | 37.072 ± 0.002s |

| B2 | 8.42 ± 0.00a | 8.51 ± 0.01fg | 35.285 ± 0.006s | 34.564 ± 0.001t |

| B3 | 8.32 ± 0.01ef | 8.28 ± 0.00m | 60.291 ± 0.003o | 122.066 ± 0.003h |

| B4 | 8.38 ± 0.01bc | 8.54 ± 0.00d | 113.494 ± 0.007i | 121.719 ± 0.006i |

| B5 | 8.31 ± 0.01f | 8.62 ± 0.01c | 13.852 ± 0.004w | 33.147 ± 0.001v |

| B6 | 8.32 ± 0.00ef | 8.49 ± 0.01h | 125.648 ± 0.009f | 143.504 ± 0.002f |

| B7 | 8.37 ± 0.00bc | 8.51 ± 0.01f-h | 57.069 ± 0.005p | 59.216 ± 0.007q |

| B8 | 8.15 ± 0.00kl | 8.47 ± 0.01i | 123.142 ± 0.004g | 115.714 ± 0.004k |

| B9 | 8.18 ± 0.00j | 8.40 ± 0.01j | 30.642 ± 0.005t | 63.868 ± 0.008p |

| B10 | 8.42 ± 0.01a | 8.54 ± 0.01d | 54.208 ± 0.002q | 58.137 ± 0.005r |

| B11 | 8.05 ± 0.00m | 8.40 ± 0.00j | 45.642 ± 0.014r | 30.649 ± 0.005w |

| B12 | 7.02 ± 0.00o | 7.12 ± 0.01o | 119.930 ± 0.001h | 117.071 ± 0.001j |

| B13 | 8.14 ± 0.01l | 8.34 ± 0.01l | 97.427 ± 0.005j | 73.867 ± 0.009o |

| B14 | 8.34 ± 0.01d | 8.56 ± 0.00de | 64.937 ± 0.001n | 98.142 ± 0.004m |

| B15 | 7.07 ± 0.01n | 7.17 ± 0.00n | 696.718 ± 0.002a | 549.208 ± 0.007a |

| B16 | 8.21 ± 0.00i | 8.52 ± 0.01f | 131.713 ± 0.003e | 124.567 ± 0.002g |

| B17 | 8.32 ± 0.00ef | 8.67 ± 0.01b | 66.359 ± 0.008l | 98.503 ± 0.008l |

| B18 | 8.36 ± 0.01c | 8.37 ± 0.01k | 23.853 ± 0.006v | 34.215 ± 0.004u |

| B19 | 8.16 ± 0.01jk | 8.39 ± 0.00j | 297.786 ± 0.002b | 225.935 ± 0.002d |

| B20 | 8.36 ± 0.01c | 8.57 ± 0.00d | 68.854 ± 0.009k | 170.993 ± 0.002e |

| B21 | 8.32 ± 0.01d-f | 8.55 ± 0.00de | 169.565 ± 0.005d | 252.083 ± 0.011c |

| B22 | 8.26 ± 0.01h | 8.50 ± 0.00gh | 65.649 ± 0.005m | 74.207 ± 0.006n |

| B23 | 8.29 ± 0.01g | 8.57 ± 0.00d | 255.635 ± 0.003c | 295.573 ± 0.003b |

| LSD | 0.0180 | 0.0181 | 0.0163 | 0.0148 |

Means followed by different superscript letters (a, b, c, etc.) differ significantly according to Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at p ≤ 0.05.

Substantial differences were also recorded in sulfate ion (SO4²–) concentrations. Isolate B15 demonstrated the highest sulfate formation after the first week to be 696.7 mg/L, compared to 119.9 mg/L by isolate B12. After 15 days of incubation, both isolates showed slight increases in pH, while sulfate concentrations declined.

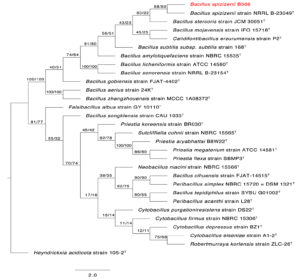

Alignment and phylogenetic analyses

To determine the phylogenetic placement of the two sulfur-oxidizing bacterial isolates SOB12 and SOB15, their 16S rRNA gene sequences were compared with those of both cultured and uncultured microorganisms within the Thiobacillus cluster and other related sulfur-oxidizing taxa. The phylogenetic affiliations of the two strains are presented in Figures 4 and 5, respectively.

Figure 4. The first of 1000 equally most parsimonious trees obtained from a heuristic search (1000 replications) of Bacillus spizizenii strain B566 (in red color) compared to other closely similar 16S rRNA sequences in GenBank. Bootstrap support values for ML/MP are indicated above/below the respective nodes. Type strains are indicated with T. The tree is rooted to Heyndrickxia acidicola strain 105-2 as outgroup

Figure 5. The first of 1000 equally most parsimonious trees obtained from a heuristic search (1000 replications) of Priestia aryabhattai strain B567 (in red color) compared to other closely similar 16S rRNA sequences in GenBank. Bootstrap support values for ML/MP are indicated above/below the respective nodes. Type strains are indicated with T. The tree is rooted to Heyndrickxia acidicola strain 105-2T as outgroup

Closely related sequences from members of the genera Bacillus and Priestia, including type strains, were retrieved from the GenBank database. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of Bacillus spizizenii strain AUMC B566 (SOB12) (Genbank Accession number PX437460) and Priestia aryabhattai strain AUMC B567 (SOB15) (Genbank Accession number PX437823), obtained in this study, were aligned alongside reference sequences using MAFFT version 6.861b with default parameters27 Alignment gaps and parsimony-uninformative regions were filtered using BMGE.28 Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using both Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Maximum Parsimony (MP) methods in PhyML version 3.0,29 and the robustness of tree topology was assessed via 1000 bootstrap replicates (Felsenstein 1985). The best-fit nucleotide substitution model for ML analysis was selected using Smart Model Selection (SMS) version 1.8.1.30

Two separate phylogenetic trees were generated: one comparing B. spizizenii AUMC B566 (Figure 4), and the other comparing P. aryabhattai AUMC B567 (Figure 5), each with their respective closest relatives based on 16S rRNA gene similarity. Both trees were rooted using Heyndrickxia acidicola strain 105-2 as the outgroup. Each tree represents one of 1000 equally parsimonious trees obtained from heuristic searches under the MP criterion.

Microbial mixotrophic behavior and ability to reduce pH and oxidize thiosulphate

Based on the initial screening results, the two isolates B12 and B15 which exhibited the greatest ability to reduce the pH in the modified thiosulfate broth medium were selected for further investigation. The data illustrated in Figure 6. showed the impact of glucose supplementation on the pH, electrical conductivity (EC), sulfate concentration (SO42-), and optical density (OD) during bacterial growth in two-week period.

Figure 6. B12 and B15 grown with (+G)/without (-G) glucose amendment achieving sulfur oxidation after 1 and 2 weeks with recorded variations in final pH, EC and OD values compared to control individually. [LSD values for pH, EC, SO4 and OD were 0.0208, 0.0138, 0.0140 and 0.0055 under B12, while were 0.0194, 0.0162, 0.0162 and 0.0126 under B15, respectively]

In the presence of glucose, B12 showed a significant increase in sulfate formation from 159.2 mg/L in the first week to 196.7 mg/L in the second week, accompanied by a slight increase in EC and pH. However, the optical density (OD) decreased over time, indicating a potential decline in biomass or metabolic activity. Without glucose, B12 formed lower amounts of sulfate (119.9-117.07 mg/L) compared to those with glucose, and the OD values were also slightly increased (0.380-0.393).

On the other hand, B15 in the presence of glucose exhibited a sharp increase in sulfur oxidation from 80.64 mg/L in the first week to 212 mg/L in the second week, accompanied by high optical density values (1.07-0.935), reflecting active microbial proliferation. The pH remained relatively acidic (~5.35).

The EC values showed minor variation over time. Interestingly, in the absence of glucose, B15 oxidized much higher levels of sulfur in both weeks (696.7 and 549.2 mg/L, respectively) compared to the glucose-supplemented treatment. Although OD values were slightly lower in the first week (0.764), they increased by the second week (0.935). The results indicated that B15 was capable of oxidizing thiosulfate under both nutrient conditions, but the presence of glucose influenced the pattern of growth and sulfate production in a distinct way.

From data analysis shown in Table 2, it could be concluded that measurements varied under types of bacteria applied and their response to growth period and glucose amendment. With either B12 and B15, pH values decreased than in control while increased from W1 to W2 with/without glucose amendment. SO4 formation increased under either B12 and B15 than control and from W1 to W2 under glucose, while it remarkably decreased under B15 in W2 than W1 without glucose. EC and dependent ionic strength for B12 and B15 decreased than control under Glucose amendment while increased under glucose absence. Both variables decreased under glucose and increased in its absence in W2 than W1.

Table (2):

Differences in individual variables measured after W1 and W2 with (+G)/without (-G) glucose amendment

| Glucose | SO4 [ppm] | pH | EC [dS/m] | Ionic st. [µmol/L] | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +G | -G | +G | -G | +G | -G | +G | -G | |||||||||

| Week | W1 | W2 | W1 | W2 | W1 | W2 | W1 | W2 | W1 | W2 | W1 | W2 | W1 | W2 | W1 | W2 |

| [Cont-B12] | 137 | 182 | 95 | 102 | -2.14 | -1.62 | -1.37 | -1.34 | -0.22 | -0.12 | 0.60 | 0.65 | -2.3 | -1.3 | 6.4 | 6.9 |

| [W2-W1] | 38 | -3 | 0.68 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 3.0 | 2.9 | ||||||||

| [Cont-B15] | 58 | 198 | 671 | 534 | -2.97 | -3.11 | -1.31 | -1.30 | -0.51 | -0.72 | 0.70 | 0.80 | -5.4 | -7.6 | 7.5 | 8.6 |

| [W2-W1] | 131 | -148 | 0.03 | 0.09 | -0.02 | 0.33 | -0.2 | 3.5 | ||||||||

According to data illustrated in Figure 6 and emphasized in Figure 7, SO42- concentration increased under B12 by 14-fold and 8-fold in the second week compared to the control with and without glucose, while pH decreased 1.6 units and 1.4 units, respectively. On the other hand, under B15, sulphate concentration increased by 15-fold and 36-fold in the second week compared to the control with and without glucose, while pH decreased 3.1 units and 1.3 units, respectively.

Figure 7. Fold increase in SO42- production and pH decrease by either B12 and B15 compared individually to control grown with (+G)/without (-G) glucose (mean of triplicates, n = 3)

Under B12, the EC and I were in positive correlation with both SO42- formation and pH values with Glucose amendment, while SO42- formation was negatively correlated with EC, I and pH, similarly under B15 when no glucose was applied in growth, as shown in Table 3. On the other hand, B15 under glucose amendment had strong positive correlation between SO42- formation and pH values, while both were in negative correlation with EC and I.

Table (3):

Correlating measured physical and chemical analyses for B12 and B15 gathering with (+G)/without (-G) glucose amendment after 1 and 2 weeks

| M.O | pH | EC, I | SO4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B12 | EC, I | 0.892 (p < 0.01) | ||

| SO4 | -0.421 (n.s.) | -0.687 (p < 0.05) | ||

| OD | -0.872 (p < 0.01) | -0.913 (p < 0.01) | 0.796 (p < 0.05) | |

| B15 | EC, I | 0.998 (p < 0.01) | ||

| SO4 | 0.996 (p < 0.01) | 0.915 (p < 0.05) | ||

| OD | -0.724 (p < 0.05) | -0.654 (p < 0.05) | -0.899 (p < 0.01) |

The oxidized S achieved by both strains had a strong relation to final variables including pH, EC and OD measurements recorded after 1 and 2 weeks of growth. Bacillus and Priestia capabilities in oxidizing S were reciprocal in correlation to measured variables, As Bacillus sp. oxidation of S was positively affected by Glucose amendment parallel to its growth magnitude (O.D), but was negatively related to final pH and EC values. This was confirmed by correlation between SO42- formation recorded against OD was +0.8 while against pH and EC recoded -0.4 and -0.7, respectively, as shown in Table 2. On the contrary, Priestia capabilities were negatively affected by Glucose amendment parallel to increase in OD and decrease in both pH and EC measured. This attitude was confirmed by strong positive correlation between SO42- formation recorded against both pH (+1.0) and EC (+0.9) while was negatively correlated with OD (-0.9). it could be concluded that glucose amendment pushed Bacillus growth parallel to SO42- formation while pushing Priestia growth decreased its capability to form SO42-. This might be explained by the ability of Priestia cells to accumulate formed SO42-.

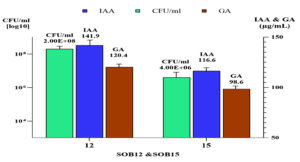

The capability of B12 and B15 to produce IAA and GA

When Bacillus and Priestia were cultivated in nutrient broth supplemented with 0.1 g/L of tryptophan and incubated at 33 ± 2 °C for three days, the concentrations of IAA and GA produced by Bacillus recorded 141.9 µg/mL and 120.4 µg/mL, respectively, at a population density of 2.0 log CFU/ml in Figure 8.

In contrast, Priestia produced 116.6 µg/mL of IAA and 98.6 µg/mL of GA at a higher population density of 4.0 log CFU/ml.

This suggested that Bacillus may had a more efficient IAA and GA biosynthetic pathway or a stronger response to tryptophan supplementation compared to Priestia, resulting in higher phytohormone production even at a lower cell density.

The molecular identification of the most efficient sulfur-oxidizing isolates revealed that isolate B12 belongs to Bacillus spizizenii strain AUMC B566, while isolate B15 was identified as Priestia aryabhattai. These isolates demonstrated a remarkable ability to oxidize thiosulfate and enhance sulfate production under both autotrophic and mixotrophic conditions.

The SEM examination suggested a strong chemotactic and consequently expected metabolic association between SOB and sulfur granules in thiosulfate enriched broth, as previously shown in Figure 1.

Overall, our findings align with previous research on marine and soil SOBs, which demonstrated enhanced growth and sulfur oxidation in mixotrophic conditions.31-34

Combining sulfur oxidation in its inorganic form with/without organic carbon assimilation clarified variation in metabolic behavior of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (SOB) as a mixotrophic

lifestyle.35,36 Sulfate production from elemental sulfur by some SOBs ranged from 317 to 1189 ppm. Some of Methylobacterium species were reported to oxidize thiosulfate under mixotrophic conditions, forming 1400 and 1080 ppm sulfate, respectively.36 Compared to presented work, B. spizizenii and P. aryabhattai formed sulfate from thiosulfate oxidation with/without glucose amendment, achieving maximum yield of 179 and 696 ppm sulfate under glucose amendment and absence, respectively.

Data illustrated in Figure 4 indicated that glucose served as an effective co-substrate, sufficiently promoting sulfate formation in thiosulfate-enriched medium by B. spizizenii as a mixotrophic behavior more than P. aryabhattai as an autotrophic behavior. In other word, the ability of B. spizizenii and P. aryabhattai to thrive in both autotrophic and mixotrophic modes confirmed that autotrophy might be a preferred and advantageous metabolic strategy enabling higher sulfate yields as with P. aryabhattai than B. spizizenii, as previously noted.

Previous studies have confirmed the ability of SOB to form significant sulfate concentrations under variable environmental conditions. Worthy to mention that, thiosulfate in aqueous solutions had been oxidized under the influence of aerial and UV light oxidation applied following second and third order reaction kinetics, respectively.37 Concerning other forms of sulfur compounds,38 Investigated hydrogen sulfide oxidation by atmospheric oxygen specifically under acidic conditions. This might explain the formation of SO42- in control when thiosulfate enriched medium was incubated for 2 weeks during which it was exposed to day light under aerobic conditions. Also, these studies emphasized the role of atmospheric oxygen and acidity in assisting thiosulfate oxidation by SOBs.39 During thiosulfate oxidation by sulfur bacteria other unexpected sulfur forms appeared including tetrathionate S4O6²– beside SO4²– and SO2²–. This explanation might have its share in the apparent decrease of SO4²– ion in W2 than W1 by 148 ppm under P. aryabhattai application without glucose, as shown in Table 2.

According to previously noted Eq. 2 added to the ion pairing theory revealed by De Visscher and Chavoshpoor,40 the oxidation of thiosulfate to sulfate ion increased anion and cation formation, that by exceeding a specific ionic strength might lead to ion pairing where opposite charged ions associated to form weakly charged species (ion pair). This might explain the unexpected decrease in ionic strength by 0.2 µmol/L after W2 parallel to increase in SO4²– ion formed by 131 ppm when P. aryabhattai was applied under glucose amendment, as shown in Table 2.

From previous research, it was reported that SOB consumed molecular oxygen and formed sulfate (SO42-) beside two protons (2H+). The resulting H+ reduced pH while both EC and ionic strength increased. EC represented the ability to carry a current proportional to the concentration of ions, serving as a proxy for the microbial activity of SOB.8,41, 42 With some types of SOBs the pH value 5-6.5 dominated SOB that used a complete sulfur oxidation pathway (CSOX) which increased acidity and S2O32- consumption. On the other hand, pH 6.5-8.5 dominated SOB that used incomplete-CSOX that limited acidity generation and was associated with higher S2O32-.

The decrease in pH of the growth medium, particularly in glucose-amended cultures, was also in agreement with the findings of Narendra et al.,43 who observed a significant pH drop from 8.0 to below 5.0, accompanied enhanced sulfate production.44 Found in their study on mineral-microbe interaction that P. aryabhattai showed fast pH drop due to acid production during growth including acetic, malic and formic acids.

This was obvious in case of B. spizizenii as in W1 pH was lower than 6.5 accompanied by increase in SO4 than control by 136.8, while in W2 the elevation of pH above 6.5 was parallel to decrease in SO4 formation increment by 37.5 (decrease by 3.6-fold, app.). added to that, in absence of glucose the pH values were above 7 leading to minimum increase in SO4 formation to be 49 in W1 and minimum decrease in SO4 formation in W2.45 Reported that B. spizizenii growth was dependent on temperature, pH and salinity achieving its best at 38.7 °C, 7.5 and 6.6 g/L (EC 11.6 dS/m), respectively. Also Elmetwalli et al.,46 Revealed that activities of oxidative extracellular enzymes produced by B. spizizenii were dependent on many environmental conditions including temperature, pH and ionic strength.

However, our results in Table 3, collectively with/without glucose, showed no clear correlation between sulfate formation with pH and EC under B. spizizenii, consistent with the findings of Rojas-avelizapa et al.,47 who suggested that pH changes may not accurately reflect sulfur oxidation efficiency. On the contrary, under P. aryabhattai the sulfate formation was in strong correlation with pH and EC values.

According to Eom et al.,41 they evaluated the activity of SOB by measuring EC where an increase of 0.1 to 0.12 dS/m was considered reliable to carry on their experiment. Meaning that any change in EC during growth lower than 0.1 dS/m proved decrease in BOS activity. Based on this explanation, the recorded increase in EC in the present work after W2 under both SOBs ranged from 0.29-0.33 dS/m proving increase in their activity, except under P. aryabhattai with glucose as EC decreased dramatically by 0.02 dS/m.

B. spizizenii was known for its role in assimilatory sulfur metabolism, essential for the biosynthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids and cofactors.48 This supported the metabolic significance of B. spizizenii under sulfur-limiting conditions. Meanwhile, P. aryabhattai has been characterized as a plant growth-promoting bacterium with sulfur-metabolizing capabilities.

On the other hand, results demonstrated that both B. spizizenii and P. aryabhattai were capable of producing phytohormones, specifically indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and gibberellic acid (GA), when grown in nutrient broth supplemented with tryptophan. However, B. spizizenii showed superior efficiency in phytohormone production, achieving higher concentrations of both IAA (141.9 µg/mL) and GA (120.4 µg/mL) at a relatively low population density (2.0 log CFU/mL). In contrast, P. aryabhattai required a significantly higher cell density (4.0 log CFU/mL) to produce lower levels of IAA (116.6 µg/mL) and GA (98.6 µg/mL). These findings suggested that B. spizizenii possessed a more efficient tryptophan-dependent biosynthetic pathway for phytohormone production, possibly due to higher enzymatic activity or more effective precursor uptake mechanisms. This is in line with previous reports describing B. spizizenii as prolific producers of plant growth-promoting substances, even under suboptimal conditions.

The lower hormonal yield by P. aryabhattai, despite a higher biomass, may indicate either a slower metabolic conversion rate or a regulatory mechanism that limits hormone synthesis beyond a certain threshold. Nevertheless, the ability of both isolates to produce substantial amounts of IAA and GA highlights their potential as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), especially in integrated biofertilizer applications aimed at enhancing root elongation, cell division, and overall plant vigor. Furthermore, P. aryabhattai was found to produce indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) when supplemented with L-tryptophan,49 suggesting that in addition to sulfur metabolism, it may promote plant growth through phytohormone production making it a promising candidate for biofertilizer development.

Compared with recent SOB studies, our isolates (Bacillus spizizenii B12 and Priestia aryabhattai B15) achieved substantial sulfate accumulation even in the absence of glucose, demonstrating their strong sulfur-oxidizing capacity under nutrient-limited conditions. In addition, the concurrent analysis of pH, EC, and OD provided a more integrated evaluation of SOB activity, which addresses a methodological gap not commonly explored in earlier reports. Recent studies have highlighted the role of SOB in improving nutrient solubilization and plant growth under sustainable agriculture. Our findings are consistent with these reports while extending them by showing high sulfate production without supplemental carbon sources, emphasizing the robustness of these isolates. Nonetheless, limitations such as the lack of soil chemical profiling and field-scale validation are acknowledged, and future research will focus on expanding the sampling design and testing the biofertilizer potential of these strains under field conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Sultan Qaboos University, Oman, for their support (Grant IG/SCI/BIOL/23/03).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

LAAM, AMM and SHAH conceived and designed the experiments. LAAM, AMM and SHAH supervised the study. LAAM, SAK and SHAH analyzed the data. SAK prepared figures and tables. LAAM, AMM, SHAH, SAK wrote the original draft. SAK wrote the manuscript. LAAM, AMM, SHAH, SAK reviewed and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

This study was supported by Sultan Qaboos University, Oman, grant number IG/SCI/BIOL/23/03.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Dawar R, Karan S, Bhardwaj S, Meena DK, Padhan

SR, Reddy KS, Bana RS. Role of sulphur fertilization in legume crops: A comprehensive review. Int J Plant Sci. 2023;35(21):718-727.

Crossref - Dordevic D, Capikova J, Dordevic S, Tremlova B, Gajdacs M, Kushkevych I. Sulfur content in foods and beverages and its role in human and animal metabolism: A scoping review of recent studies. Heliyon. 2023;9(4):e15452.

Crossref - Nwankwo NE, David JC. A review of sulfur-containing compounds of natural origin with insights into their Pharmacological and toxicological impacts. Discov Chem. 2025;2(1):207.

Crossref - Zhou Z, Tran PQ, Cowley ES, Trembath-Reichert E, Anantharaman K. Diversity and ecology of microbial sulfur metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2025;23(2):122-140.

Crossref - Jin X, Wang H, Wu Q, Zhang J, Li S. Multifunctional role of the biological sulfur cycle in wastewater treatment: Sulfur oxidation, sulfur reduction, and sulfur disproportionation. Desalination Water Treat. 2025;322:101100.

Crossref - Gao P, Fan K. Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (SOB) and sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) in oil reservoir and biological control of SRB: a review. Arch Microbiol. 2023;205(5):162.

Crossref - Rana K, Rana N, Singh B. Applications of sulfur oxidizing bacteria. In: Salwan R, Sharma V (eds). Physiological and Biotechnological Aspects of Extremophiles. Academic Press. 2020:131-136.

Crossref - Oh SE, Hassan SHA, van Ginkel SW. A novel biosensor for detecting toxicity in water using sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2011;154(1):17-21.

Crossref - McNeice J, Mahandra H, Ghahreman A. Biogenesis of thiosulfate in microorganisms and its applications for sustainable metal extraction. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2022;21(4):993-1015.

Crossref - Chen SC, Li X M, Battisti N, et al. Microbial iron oxide respiration coupled to sulfide oxidation. Nature. 2025;646(8086):925-933.

Crossref - Starkey RL. Concerning the physiology of Thiobacillus thiooxidans, an autotrophic bacterium oxidizing sulfur under acid conditions. J Bacteriol. 1925;10(2):135-163.

Crossref - Malviya D, Varma A, Singh UB, Singh S, Singh HV, Saxena AK. Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria from coal mine enhance sulfur nutrition in pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L.). Front Environ Sci. 2022;10:932402.

Crossref - Vidyalakshmi R, Sridar R. Isolation and characterization of sulphur oxidizing bacteria. J Culture Collections. 2006–2007;5:73-77

- Parker CD, Prisk J. The oxidation of inorganic compounds of sulphur by various sulphur bacteria. Microbiology. 1953;8(3):344-364.

Crossref - Lindqvist R. Estimation of Staphylococcus aureus growth parameters from turbidity data: characterization of strain variation and comparison of methods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(7):4862-4870.

Crossref - Kurmanbayeva A, Brychkova G, Bekturova A, Khozin I, Standing D, Yarmolinsky D, Sagi M. Determination of total sulfur, sulfate, sulfite, thiosulfate, and sulfolipids in plants. In: Plant Stress Tolerance: Methods and Protocols. New York, NY: Springer; 2017:253-271.

Crossref - Woszczyk M, Stach A, Nowosad J, Zawiska I, Bigus K, Rzodkiewicz M. Empirical formula to calculate ionic strength of limnetic and oligohaline water on the basis of electric conductivity: implications for limnological monitoring. Water. 2023;15(20):3632.

Crossref - Senthilkumar M, Amaresan N, Sankaranarayanan A. Quantitative Estimation of Sulfate Produced by Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacteria. In: Plant-Microbe Interactions. Springer Protocols Handbooks. Humana, New York, 2020:73-75.

Crossref - Kolmert A, Wikstrom P, Hallberg KB. A fast and simple turbidimetric method for the determination of sulfate in sulfate-reducing bacterial cultures. J Microbiol Methods. 2000;41(3):179-184.

Crossref - Glickmann E, Dessaux Y. A critical examination of the specificity of the Salkowski reagent for indolic compounds produced by phytopathogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61(2):793-796.

Crossref - Udagawa K, Kinoshita S. A colorimetric determination of gibberellin A32 specificity of determination. Nippon Nogei Kagaku Kaishi. 1961;35(3):224.

Crossref - Khalida Khan KK, Muhammad Naeem MN, Arshad MJ, Muhammad Asif MA. Extraction and chromatographic determination of caffeine contents in commercial beverages. Journal of Applied Sciences. 2006;6(4): 831-834

Crossref - Zimbro MJ, Power DA, Miller SM, Wilson GE, Johnson JA. Difco & BBL manual. Manual of Microbiological Culture Media. 2009;7.

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee SJWT, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Academic Press. 1990;18(1):315-322.

Crossref - Mahmoud OH, Essa SK. Using a scanning electron microscope in diagnosing of clay minerals in some Iraqi rice soils. Iraqi J Market Res Consum Prot. 2024;16(1):100-110.

Crossref - Duncan DB. Multiple range and multiple F tests. Biometrics. 1955;11(1):1-42.

Crossref - Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772-780.

Crossref - Criscuolo A, Gribaldo S. BMGE (Block Mapping and Gathering with Entropy): a new software for selection of phylogenetic informative regions from multiple sequence alignments. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10(1):1-21.

Crossref - Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59(3):307-321.

Crossref - Lefort V, Longueville JE, Gascuel O. SMS: smart model selection in PhyML. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34(9):2422-2424.

Crossref - Li J, Xiang S, Li Y, et al. Arcobacteraceae are ubiquitous mixotrophic bacteria playing important roles in carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycling in global oceans. Msystems. 2024;9(7):e00513-24.

Crossref - Rolando JL, Kolton M, Song T, et al. Sulfur oxidation and reduction are coupled to nitrogen fixation in the roots of the salt marsh foundation plant Spartina alterniflora. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):3607.

Crossref - De Corte D, Muck S, Tiroch J, Mena C, Herndl G J, Sintes E. Microbes mediating the sulfur cycle in the Atlantic Ocean and their link to chemolithoautotrophy. Environ Microbiol. 2021;23(11):7152-7167.

Crossref - Wang W, Li Z, Zeng L, Dong C, Shao Z. The oxidation of hydrocarbons by diverse heterotrophic and mixotrophic bacteria that inhabit deep-sea hydrothermal ecosystems. ISME J. 2020;14(8):1994-2006.

Crossref - Hassan SHA, Van Ginkel SW, Kim SM, Yoon SH, Joo JH, Shin BS, Oh SE. Isolation and characterization of Acidithiobacillus caldus from a sulfur-oxidizing bacterial biosensor and its role in detection of toxic chemicals. J Microbiol Methods. 2010;82(2):151-155.

Crossref - Anandham R, Indiragandhi P, Madhaiyan M, et al. Thiosulfate oxidation and mixotrophic growth of Methylobacterium goesingense and Methylobacterium fujisawanse. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;19(1):17-22.

- Ahmad N, Ahmad F, Khan I, Khan AD. Studies on the oxidative removal of sodium thiosulfate from aqueous solution. Arab J Sci Eng. 2015;40(2):289-293.

Crossref - Rathore DS, Meena VK, Chandel CPS, Gupta KS. Kinetics of the oxidation of hydrogen sulfide by atmospheric oxygen in an aqueous medium. J Atmos Sci Res. 2021;4(3):46-59.

Crossref - Houghton JL, Foustoukos DI, Flynn TM, Vetriani C, Bradley AS, Fike DA. Thiosulfate oxidation by Thiomicrospira thermophila: metabolic flexibility in response to ambient geochemistry. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18(9):3057-3072.

Crossref - De Visscher A, Chavoshpoor N. Incorporating ion pairing in an extended specific ion theory: 2-2 electrolytes. 2022.

Crossref - Eom H, Kim S, Oh SE. Evaluation of joint toxicity of BTEX mixtures using sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. J Environ Manag. 2023;325:116435.

Crossref - Twible LE, Whaley-Martin K, Chen LX, et al. pH and thiosulfate dependent microbial sulfur oxidation strategies across diverse environments. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1426584.

Crossref - Reddy NN, Ratnam MV, Basha G, Ravikiran V. Cloud vertical structure over a tropical station obtained using long-term high-resolution radiosonde measurements. Atmos Chem Phys. 2018;18(16):11709-11727.

Crossref - Yang H, Lu L, Chen Y, Ye J. Transcriptomic analysis reveals the response of the bacterium Priestia aryabhattai SK1-7 to interactions and dissolution with potassium feldspar. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2023;89(5):e0203422.

Crossref - Ringleben L, Weise T, Truong HTT, Anh LH, Pfaff M. Experimental and model-based characterisation of Bacillus spizizenii growth under different temperature, pH and salinity conditions prior to aquacultural wastewater treatment application. Biochem Eng J. 2022;187:108630.

Crossref - Elmetwalli A, Allam NG, Hassan MG, et al. Evaluation of Bacillus aryabhattai B8W22 peroxidase for phenol removal in wastewater effluents. BMC Microbiol. 2023;23(1):119.

Crossref - Rojas-Avelizapa NG, Gomez-Ramirez M, Hernandez-Gama R, Aburto J, Garcia de Leon R. Isolation and selection of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria for the treatment of sulfur-containing hazardous wastes. Chem Biochem Eng Q. 2013;27(1):109-117.

- Sekowska A, Denervaud V, Ashida H, et al. Bacterial variations on the methionine salvage pathway. BMC Microbiol. 2004;4(1):9.

Crossref - Wang F, Chu Y, Yan Z. A study on the factors influencing the consumption of virtual gifts on a live streaming platform based on virtual badges and user interaction. Electron Commer Res. 2024:1-29.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.