ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Soil microorganisms, as the sole component, play a major role in nurturing agricultural productivity and regulating soil health by affecting biological and biochemical processes and soil functioning. Among soil microorganisms, yeasts are present at a greater order of magnitude in the rhizosphere region depending on their nutritional preference. More than half of soil yeasts exhibit a variety of positive effects on plants, viz., plant growth promotion, phosphate solubilization, nitrogen and sulfur oxidation, siderophore production, and stimulation of mycorrhizal root colonization. With this prelude, work with the core idea of isolating soil yeasts from distinct soil ecosystems and evaluating their impact on plant growth was carried out. From the experiments performed, 61 isolates were identified, and 16 were selected for further investigation of their ability to promote plant growth via molecular screening. Of the sixteen isolates, fifteen exhibited the ability to solubilize phosphate and one isolate out performed the reference strain. Thirteen isolates were found to possess the zinc solubilization potential and 14 released potassium efficiently. All sixteen yeast isolates were found to produce indole acetic acid and gibberellic acid in considerable amounts. In addition, the antimicrobial traits were also evidenced by siderophore production by all sixteen isolates and HCN production by one yeast isolate. The principal component analysis correlated the growth-promoting abilities of the yeast isolates. The results showed that soil yeasts possess the potential to be used as microbial inoculants for plant growth promotion.

Soil Yeast, Plant Growth Promotion, Growth Hormone, Siderophore

The health of the soil is determined by the interaction between its macro- and micro living entities, as well as environmental conditions. Soil contains millions of microorganisms exhibiting significant impact on the biogeochemical cycling of nutrients in soil; hence, they are involved in plant growth promotion and soil health maintenance. Fungi make a significant contribution to both genetic diversity and soil microbial biomass.1,2 Unicellular fungi, such as yeasts, have extensive utility in the food and agro-based sectors. Yeasts are ubiquitous in the environment, and formal research indicates that ongoing investigations primarily revolve around the taxonomic diversity of yeasts. However, their significance in the domain of plant growth promotion and soil health maintenance remains unexplored. Compared with soil yeasts, many soil bacteria and fungi have been exploited as bioinoculants to their fullest potential. There are few reports on the beneficial activities of yeasts, including the production of siderophores,3 the stimulation of mycorrhizal root colonization,4 phosphate solubilization,5 zinc solubilization,6 the release of potassium,6 nitrogen,7 sulfur oxidation7 and the production of plant growth-promoting hormones, viz., IAA8 and GA3.9 Extracellular polymeric substances produced by yeasts facilitate the bonding of soil particles and promote the formation of soil aggregates. Soil yeast positively influences soil physical, chemical and biological properties. Hence, there is an increase in the need to explore the diversity and role of yeast in plant growth promotion and soil health maintenance. An investigation into the potential of yeast bioinoculants to promote crop growth and soil health can result from an evaluation of the functional diversity of yeasts in plant and soil health.5,10 Recent research has shown that some yeast species can promote plant growth and maintain soil structure.11 A clear understanding of the various roles of soil yeasts will serve as a key to sustainable agriculture in the future.12

Yeasts continue to be underutilized as biofertilizers, in contrast to filamentous bacteria and fungi. Soil yeast research in India is currently in its nascent phase, despite its capacity to promote plant growth and maintain soil structure. To date, only a few drifts have been found to implement yeast as a biofertilizer. Biofertilizers is an important component of integrated nutrient management (INM).13 Combined application of biofertilizers14 and application of location-specific biofertilizers15 are gaining momentum in the field of INM and yeasts is an excellent component for these two avenues. The fruit weight of tomato plants increased with the application of Rhodotorula sp., according to a report by Abd El-Hafez.16 Additionally, Edi-Premono et al.17 demonstrated an increase in yield in wheat ranging from 16% to 30% with the application of Sporobolomyces roseus. Shih et al.18 reported a range of yeast activities, such as the stimulation of plant growth and the synthesis of polyamines (e.g., ammonia), siderophores, IAA, and enzymes such as ACC deaminase. Yeasts also serve as a model organism for many of the bioefficacy studies. Viana et al.,19 studied the antibiofilm potential of Vassobia breviflora (Sendtn.) Hunz A. plant extract against P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, S. aureus, E. faecium and S. epidermidis. As yeast is also a potential biofilm producer, this may serve as a model organism for such bioefficacy studies.

Soil microbial abundance and diversity vary according to climatic conditions and ecosystem type.20 A great variety of factors, such as soil type, ecosystem, anthropogenic activities, cropping pattern, temperature, soil pH, moisture, and nutrients, affect soil microbial diversity and abundance. The isolation of microorganisms from different ecosystems for specific purposes, such as plant growth promotion, will result in the collection of diverse potential isolates. Though growing evidence shows that yeasts have numerous plant growth-promoting properties, their significance in preserving soil fertility and increasing crop productivity is usually neglected when compared to bacteria and filamentous fungi. Considering the critical need for sustainable and environmentally friendly alternatives to chemical fertilizers, investigating native soil yeasts as possible bioinoculants might have a substantial impact on sustainable agriculture and soil health management. Therefore, the current work aimed to isolate, characterize, and assess soil yeasts with plant growth-promoting potential from various soil ecosystems with the goal to identify possible candidates for future biofertilizer development.

Isolation of soil yeasts

Soil samples were collected from dryland, wetland and garden land ecosystems (Table 1). Soil samples were collected upto a depth of 15 cm at random sites and then pooled together. Representative soil samples were placed into labeled, 18 x 13 cm zip lock cover and stored under refrigerated condition. Soil yeasts were isolated via serial dilution and the pour plate technique. One gram of soil sample was transferred to 100 ml of sterile water blank taken in 250 ml conical flask to get 10-2 dilution and the flask was swirled for five minutes in both clockwise and anti-clockwise directions and kept undisturbed for two minutes for settling down of the soil particles. One ml of 10-2 diluent was transferred to 9 ml of sterile water blank taken in test tubes and mixed well to get 10-3 dilution. The same procedure was repeated to get 10-4 dilution. One ml of the diluent from 10-4 dilution was used for isolation of yeasts. Two different media were used: yeast extract malt extract (YEME) (yeast extract-3 gl-1, malt extract-3 gl-1, peptone-5 gl-1, dextrose-10 gl-1, agar-20 gl-1, pH-5.5-6.5)21 and yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) (yeast extract-10 gl-1, peptone-20 gl-1, dextrose-20 gl-1, agar-20 gl-1, pH-5.5-6.5).22 One ml from 10-4 dilution was transferred to sterile petridish and 15-20 ml respective media at molten state were added. The inoculated plates were incubated at 28 °C for 2-3 days. Well-grown yeast colonies were selected and purified by the streak plate method on the respective media, and the cells were morphologically characterized under a microscope.

Table (1):

Details of the soil samples collected

Soil Yeast |

Location |

Latitude |

Longitude |

Sample details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

SY1 |

Thondi |

9°46’35″N |

79°00’28″E |

Gardenland (Black gram) |

SY2 |

Thondi |

9°46’35″N |

79°00’28″E |

Gardenland (Black gram) |

SY3 & SY4 |

TNAU |

11°00’34.5″N |

76°55’54.4″E |

Orchard (Sapota) |

SY5 |

Thondi |

9°46’35″N |

79°00’28″E |

Forest |

SY6 & SY7 |

TNAU |

11°00’34.5″N |

76°55’54.4″E |

Orchard (Mango) |

SY8 |

Thondi |

9°46’35″N |

79°00’28″E |

Saline |

SY9 & SY12 |

TNAU |

11°00’34.5″N |

76°55’54.4″E |

Orchard (papaya) |

SY10 |

Thondi |

9°46’35″N |

79°00’28″E |

Wetland (Paddy) |

SY11 |

Thiruvadanai |

9°47’0″N |

78°55’10″E |

Wetland (Paddy) |

SY13 |

TNAU |

11°00’34.5″N |

76°55’54.4″E |

Gardenland (Redfort) |

SY14 & SY15 |

TNAU |

11°00’34.5″N |

76°55’54.4″E |

Orchard (Grapes) |

SY16 |

TNAU |

11°00’34.5″N |

76°55’54.4″E |

Gardenland (Redfort) |

Molecular characterization of soil yeasts

Yeast DNA isolation was performed by the Lysis method, and 18S rRNA was amplified in a thermal cycler.23 The 18S primers used for PCR were ITS 1 as the forward primer and ITS 4 as the reverse primer.

Isolation of genomic DNA from yeast

Yeast colonies were picked from the YEME and YPD plates, inoculated into 30 mL of broth and grown in a shaking water bath at 30 °C for approximately 24 h. Cells from 1.5 mL of the 24 h-grown cultures were pelleted in a microcentrifuge tube, and the cell pellets were resuspended in 200 µl of lysis buffer. The tubes were placed in dry ice (-80 °C) for two minutes until they were completely frozen and then immersed in a 95 °C water bath for 1 minute to thaw quickly. The process was repeated once, and the tubes were vortexed vigorously for 30 seconds. Two hundred microliters of chloroform was added, and the tubes were vortexed for 2 min and then centrifuged for 3 min at room temperature at 10,000 rpm. The aqueous layer was transferred to a tube containing 400 µl of ice-cold 100% ethanol, and the samples were mixed by inversion or gentle vortexing. They were kept at -20 °C overnight to increase the yield. The samples were subsequently centrifuged for 5 min at room temperature at 10,000 rpm. The supernatants were discarded, and the DNA pellets were washed with 0.5 mL of 70% ethanol, followed by drying for five minutes at 60 °C.

DNA was resuspended in 20 µl of TE [10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0)]. Occasionally, cellular debris remains in the samples, but it does not interfere with subsequent analyses. The debris was removed by using 200 µl of phenol chloroform (1:1) instead of only chloroform during the organic extraction step. The DNA was stored at -20 °C for further use.

Purity of DNA

The purity of the DNA was further analysed by using a NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific, Nanodrop 2000c) spectrophotometer. The absorbance of the nucleic acid sample was measured at wavelengths of 260 nm and 280 nm, and the 260/280 ratio was used to assess the purity of the nucleic acids. A ratio of 1.8 to 2 indicated that the DNA preparation was pure and free from protein.

Amplification of 18S rRNA

The genomic DNA isolated from soil yeasts was amplified using the primers ITS1

(5’-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3’) and ITS4 (5’-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3’), with the reaction mixture in each tube consisting of 20 µl of 50 ng of DNA template, 1x Taq buffer, 0.2 mM of each dNTP mixture, 1 µM of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Bangalore Genei, India).

PCR amplification was performed in a thermal cycler (Bio-Rad T-100TM, USA) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 90 s, annealing at 50 °C for 45 s, extension at 72 °C for 90 s, and final elongation at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel.24

Agarose gel electrophoresis

Agarose gel electrophoresis was performed to check the quality of the DNA and to separate the products amplified through polymerase chain reaction (PCR).24 A total of 500 mL of 1X TBE tank buffer was added to each sample to fill the electrophoresis tank and prepare the gel. Agarose (0.8% for genomic DNA and 1.5% for PCR products) was added to 100 mL of 1X TBE buffer, boiled until the agarose completely dissolved and cooled to a low temperature. Ethidium bromide (50 mg/mL stock) was added at a rate of 5 µl per 100 mL of agarose solution and mixed thoroughly. It was then poured into a gel mould with the comb placed properly and allowed to solidify for half an hour at room temperature. After solidification, the comb was removed carefully. The caste gel was placed in an electrophoresis tank containing 1X TBE buffer with the well near the cathode and submerged to a depth of 1 cm. Fifteen microliters of the PCR product was mixed with 3 µl of 6X tracking dye and mixed well. The mixture was loaded into the wells with a micropipette. Six microliters of a ready-to-use 1 kb DNA ladder (Fermentas, USA) (500 ng of DNA/lane) was loaded in one of the wells as a standard marker. The cathode and anode were connected to a power pack using a power cord, and the gel was run at a constant voltage of 60 volts. The negatively charged DNA molecules move towards the anode and are separated according to their molecular weight. The power was turned off when the tracking dye migrated an appropriate distance in the gel, the gel was viewed in a UV trans illuminator, and the banding pattern was analysed and documented in a Gel Doc TM XR+ documentation system (Bio-Rad, Inc., USA).

Plant growth-promoting traits

Phosphate solubilization

Sperber’s hydroxyapatite media (glucose-10 gl-1, yeast extract-0.2 gl-1, MgSO4-0.1 gl-1, (NH4)2SO4-0.1 gl-1, KCl-0.2 gl-1, soil extract-200 ml, K2HPO4-40 ml. CaCl2-60 ml, Agar-20 g, pH 7.0) was used for screening the yeast isolates for phosphate solubilization.25 Approximately 15-20 ml of media was poured in a petri dish of 100 mm size. Plates were inoculated with 105 (±5 × 105) cells by adjusting the cell optical density to 0.5 using a spectrophotometer and incubated for 2-3 days at 30 °C. Bacillus megaterium var. phosphaticum Pb1 was used as a reference strain. After the incubation period, a clear zone was observed around the colony, and the clearing zone diameter was measured. The ability of the yeast isolates to solubilize insoluble phosphorus was described by the solubilization index (SI):

The solubilization index was calculated by using the formula:

Solubilization% = Zone + Colony diametere – Colony Diameter / Zone + Colony diametere × 100

Zinc solubilization potential

Bunt and Rovira media (Peptone-1 gl-1, yeast extract-1 gl-1, glucose-20 gl-1, (NH4)2SO4-0.05 gl-1, K2HPO4–0.40 gl-1, MgCl2-0.1 gl-1, FeCl2-0.1 gl-1, zinc oxide-1 gl-1, soil extract-250 ml, agar-15 gl-1, pH-6.6-7.0) were used for the zinc solubilization assay.26 Approximately 15-20 ml of media was poured in petri dish of 100 mm size. The plates were inoculated with the yeast isolates as mentioned above and incubated for 2-3 days at 30 °C. After the incubation period, the plates were observed for clear zone formation. Enterobacter cloacae ZSB 14 was used as the reference strain. The zinc solubilization index was calculated as described in section 2.3.1.

K Release potential

Aleksandrov media (Glucose-5 gl-1, MgSO4– 0.5 gl-1, FeCl2-0.005 gl-1, CaCl2-0.1 gl-1, CaPO4-2 gl-1, potassium aluminum silicate-2 gl-1, and agar-15 gl-1, pH 8.5) were used to study the potassium release potential of the strains.27 The agar plates were prepared by adding 15-20 ml of Aleksandrov media to petriplates of 100 mm. The agar plates were inoculated with the yeast isolates and incubated for 2-3 days at 30 °C. After the incubation period, the plates were observed for clear zone formation. Bacillus mucilaginosus KRB 9 was used as the reference strain for this experiment. The potassium solubilization index was calculated as described in section 2.3.1.

Production of growth hormones

IAA production

Yeast isolates were grown overnight in YEME broth and transferred to fresh YEME broth supplemented with 0.1% L-tryptophan as a precursor for IAA production. The cultures were incubated for 7 days at 28 °C without any interference from light and then centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min. One milliliter of the supernatant was mixed with 2 mL of Salkowski reagent (2 mL of 0.5 M FeCl3·6H2O in 98 mL of 35% perchloric acid) and incubated in the dark for 45 min. The concentration of IAA was calculated from a standard curve of IAA obtained in the range of 0.5-10.0 g mL-1 by measuring the absorbance of the samples and standards at 530 nm. Three replications were performed for each sample.28

GA3 production

The yeast isolates were subsequently grown in YEME broth at 30 °C for 7 days. After the incubation period, the culture broth was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, after which the supernatant was collected. Then, the cell pellet was re-extracted with phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and pooled, and the pH of the supernatant was adjusted to 2.0 using 1 N HCl. An equal volume of ethyl acetate was added, and the organic phase was extracted using a separating funnel. Then, 2 mL of zinc acetate solution was added to 5 mL of the collected residue. After two minutes, 2 mL of potassium ferrocyanide solution was added, and the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. Then, 5 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 5 mL of 30% HCl and incubated for 75 mins. The blank was prepared with 5% HCl. The absorbance was measured at 254 nm in a spectrophotometer.29

Siderophore production

Qualitative assay

The production of siderophores was tested by performing a plate assay.30 Cultures were streaked on succinate media supplemented with CAS (Chrome Azurol S) as an indicator. The result was based on the colour change of the medium from violet to fluorescent yellow.

Quantitative assay

Yeast isolates were inoculated in YEME broth and incubated for 48 h in a shaker at 125 rpm. The supernatant was obtained from 0.5 mL of inoculated broth containing 108 CFU mL-1. The supernatant and CAS reagents were added at a 1:1 ratio and incubated. After the incubation period, the OD of each sample was measured at 630 nm.3 Four replicates were taken for each sample. Siderophore production was calculated using the following formula:

Siderophore (%) = Ar – As / Ar × 100

Ar – Absorbance of reference (CAS solution and uninoculated broth)

As – Absorbance of the sample (CAS solution and cell-free supernatant)

HCN production

Yeast isolates were streaked on YEME media supplemented with glycine at a rate of 4.4 g/L. Filter papers were cut into pieces with a size of 1×1 cm2 and dipped in picric acid solution (2.5 g of picric acid and 12.5 g of Na2CO3 in one liter of water). After soaking, the filter paper was placed on top of a petri plate containing inoculum and allowed to incubate for 48 h at 30 °C. Positive results were noted by the colour change of the disc from yellow to brown or reddish brown.31

Antagonistic activity

The antagonistic activity of the yeast isolates against Pythium sp., a soil-borne pathogen, was screened in vitro by using potato dextrose agar (PDA) media. A dual plate assay.32 was performed to detect the antagonistic activity of the selected yeast isolates against Pythium sp. Each yeast isolate was inoculated in one half of the Petri plate, and the other half was inoculated with the pathogen. The inoculated plates were incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 2-3 days. The diameter of the inhibition zone was measured and compared with that of the control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 for Windows (IBM, Inc., Armonk, NY, USA), and the results are expressed as the mean values of three replicate analyses. Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to distinguish the yeast isolates collected from different fields. Significant differences between means were identified using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test at P = 0.05. Subsequently, relationships between plant growth-promoting traits and soil yeasts were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation tests.

Soil yeast isolation and identification

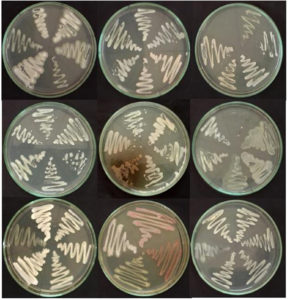

The isolates were identified by examination of their colony features, cellular morphology and microscopic inspection. Following the incubation period, colonies with a creamy appearance and devoid of a shiny appearance were isolated and preserved for subsequent investigations. A total of 61 isolates were chosen based on their morphological characteristics (Figure 1).

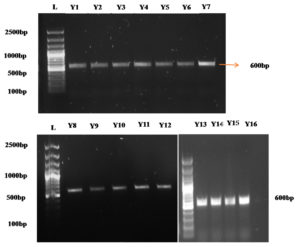

The yeast isolates were subjected to molecular characterization using 18S rRNA gene amplification. DNA from the 23 yeast isolates was extracted, and the DNA bands were visualized by a gel casting system using 1% agarose gel and then observed in a gel documentation system. There was clear band formation, and they were further subjected to specific amplification by PCR. The purity and quantity of the DNA in the nanodrops were estimated by spectrophotometry. The DNA concentration of the samples ranged from 100 ng/µl to 900 ng/µl, and the samples were also analysed on a 1% agarose gel for purity. An A260/A280 ratio of 1.80 for the DNA indicated that there was no protein or RNA contamination. The isolated DNA was subjected to PCR amplification. This was accomplished by amplification of the 18S rRNA gene using the primers ITS 1 as the forward primer and ITS 4 as the reverse primer. Sixteen of the 61 isolates were determined to be yeasts by molecular screening (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The 18S rDNA of the yeast isolates was amplified using the primers ITS1 F and ITS4 R. L – 100 bp Ladder, T – DNA. Y – Yeast DNA; Y1-Y16: Soil yeast isolates

Screening of soil yeasts for plant growth-promoting traits

Phosphate solubilization

Sperber’s hydroxy apetite medium was used to evaluate the phosphate solubilization potential of the sixteen identified isolates. The isolated yeasts were allowed to grow by streaking over the plated medium and incubating for 3 days. Among the 16 yeast isolates, 15 exhibited the ability to dissolve the inorganic phosphate found in the medium. Overall, SY16 had a greater solubilization potential percentage (59.77 ± 4.18) than did the reference strain Bacillus megaterium var. phosphaticum Pb1 (57.18 ± 4.00), followed by SY13 (58.50 ± 4.10) (Table 2). The SY1, SY2 and SY3 isolates had comparable phosphate solubilization indices, with SY1 at 22.99 ± 1.61%, SY2 at 21.94 ± 1.54% and SY3 at 22.32 ± 1.56%.

Table (2):

Mineral solubilization efficiency of soil yeast isolates

Isolates |

P solubilization (%) |

Zn solubilization (%) |

K releasing potential (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

SY1 |

22.99 ± 1.61 |

70.00 ± 4.90 |

19.61 ± 1.37 |

SY2 |

21.94 ± 1.54 |

80.00 ± 5.60 |

15.89 ± 1.11 |

SY3 |

22.32 ± 1.56 |

56.25 ± 3.94 |

33.05 ± 2.31 |

SY4 |

24.25 ± 1.70 |

63.15 ± 4.42 |

38.81 ± 2.72 |

SY5 |

2.26 ± 0.16 |

53.87 ± 3.77 |

11.55 ± 0.81 |

SY6 |

36.05 ± 2.52 |

50.00 ± 3.50 |

8.92 ± 0.62 |

SY7 |

29.33 ± 2.05 |

52.67 ± 3.69 |

11.07 ± 0.78 |

SY8 |

9.58 ± 0.67 |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

SY9 |

19.64 ± 1.38 |

61.53 ± 4.31 |

39.73 ± 2.78 |

SY10 |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

SY11 |

28.66 ± 2.01 |

0.00 ± 0.00 |

12.59 ± 0.88 |

SY12 |

38.18 ± 2.67 |

23.07 ± 1.62 |

58.33 ± 4.08 |

SY13 |

58.50 ± 4.10 |

25.00 ± 1.75 |

16.36 ± 1.15 |

SY14 |

48.53 ± 3.40 |

50.00 ± 3.50 |

19.76 ± 1.38 |

SY15 |

29.61 ± 2.07 |

60.00 ± 4.20 |

51.59 ± 3.61 |

SY16 |

59.77 ± 4.18 |

61.53 ± 4.31 |

17.08 ± 1.20 |

Ref. strain |

57.18 ± 4.00 |

53.33 ± 3.73 |

59.25 ± 4.15 |

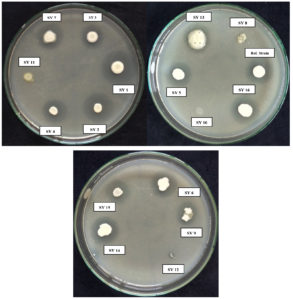

Zinc solubilization

The ability of 13 isolates to dissolve zinc was recorded. The results showed that eight isolates displayed better zinc solubilization efficiency (>53%) than the standard reference strain. The SY2 isolate had superior zinc solubilization ability, achieving a maximum solubilization index of 80.00%. This was followed by isolates SY1 (70.00 ± 4.90%), SY4 (63.15 ± 4.42%), SY9 (61.53 ± 4.31%), SY16 (61.53 ± 4.31%), SY3 (56.25 ± 3.94%) and SY5 (53.87 ± 3.77%) (Figure 3). The three isolates SY8, SY10, and SY11 were inefficient at solubilizing zinc.

Potassium release potential

Potassium release was observed for fourteen isolates, yet potassium release was less common than P and Zn solubilization. The potassium release potential of the single SY12 isolate (58.33 ± 4.08%) was comparable to that of the reference strain Bacillus mucilaginosus KRB 9 (59.25 ± 4.15%).

Plant growth hormone production

IAA production

The results of quantifying the IAA produced by the yeast isolates to identify the highest IAA producer are indicated in Table 3. The presence of IAA was confirmed by the culture supernatant turning purplish red following the addition of Salkowski reagent. All sixteen isolates produced IAA. The isolate with the highest IAA production was SY1 (35.42 ± 2.48 µg mL-1), followed by SY4 and SY7. The IAA production was lowest in SY15, SY13, SY14, SY2 and SY16.

Table (3):

Plant growth hormone and siderophore production by soil yeast isolates

Isolates |

IAA Production (µg mL-1) |

GA3 Production (µg mL-1) |

Siderophore production (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

SY1 |

35.42 ± 2.48 |

726.32 ± 50.84 |

8.77 ± 0.61 |

SY2 |

2.43 ± 0.17 |

2581.86 ± 180.73 |

6.49 ± 0.45 |

SY3 |

23.12 ± 1.62 |

279.46 ± 19.56 |

16.47 ± 1.15 |

SY4 |

32.82 ± 2.30 |

454.63 ± 31.82 |

12.36 ± 0.87 |

SY5 |

21.15 ± 1.48 |

1026.61 ± 71.86 |

3.02 ± 0.21 |

SY6 |

29.90 ± 2.09 |

454.54 ± 31.82 |

61.77 ± 4.32 |

SY7 |

33.89 ± 2.37 |

1145.07 ± 80.15 |

10.32 ± 0.72 |

SY8 |

3.83 ± 0.27 |

1146.54 ± 80.26 |

29.31 ± 2.05 |

SY9 |

11.64 ± 0.81 |

597.22 ± 41.81 |

65.95 ± 4.62 |

SY10 |

18.03 ± 1.26 |

362.22 ± 25.36 |

27.43 ± 1.92 |

SY11 |

8.01 ± 0.56 |

455.58 ± 31.89 |

3.11 ± 0.22 |

SY12 |

12.34 ± 0.86 |

767.65 ± 53.74 |

1.31 ± 0.09 |

SY13 |

1.26 ± 0.09 |

25.28 ± 1.77 |

16.43 ± 1.15 |

SY14 |

1.36 ± 0.10 |

899.57 ± 62.97 |

24.22 ± 1.70 |

SY15 |

0.67 ± 0.05 |

650.28 ± 45.52 |

2.41 ± 0.17 |

SY16 |

3.64 ± 0.26 |

525.18 ± 36.76 |

1.31 ± 0.09 |

Gibberellic acid production

According to the experimental data, the yeast isolates generated GA3 at a rate ranging from 25.28 ± 1.77 to 2581.86 ± 180.73 µg mL-1. A greater quantity of gibberellic acid (2581.86 ± 180.73 µg mL-1) was produced by SY2, followed by SY8 and SY5 (Table 3).

Siderophore production

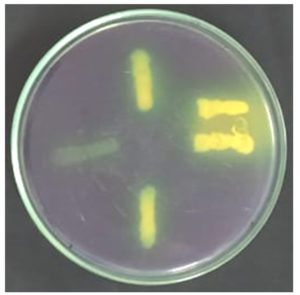

Qualitative assay

Siderophore production was confirmed for all 16 isolates by positive results from the plate assay (Figure 4) and was quantified using a spectrophotometer.

Quantitative assay

The supernatant from the centrifugation of the broth-grown isolates was utilized to determine the amount of siderophores produced. The SY9 isolate generated the greatest quantity of siderophores at 65.95 ± 4.62%, followed by SY6 at 61.77 ± 4.32%. The quantity of siderophores produced by the soil yeast isolates is presented in Table 3.

HCN production

The cultures were evaluated for the production of HCN. Only isolate SY4 produced HCN, which was confirmed by the transformation of the yellow to brown color of the filter paper. The rest of the isolates were incapable of secreting HCN.

Antagonistic activity

The outcomes of the dual plate assay for antagonistic activity revealed that soil yeasts have the potential to function as antagonists against Pythium sp., a soil pathogen. The diameter of the inhibition zone produced by the soil yeast isolates against the pathogen ranged from 1 mm to 4.1 mm. Pythium sp. was effectively inhibited by the yeast isolate SY4.

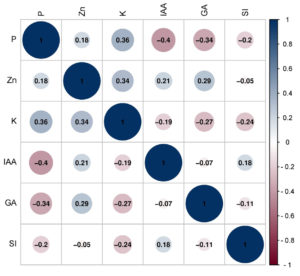

Correlation analysis

Correlation analysis was performed for all the plant growth-promoting traits of the soil yeasts. Pearson correlation was determined between the roles of yeasts in soil and the positive and negative correlations. P was positively correlated with Zn solubilization (r = 0.182) and K release potential (r = 0.361), whereas P was negatively correlated with IAA (-0.404), GA (r = -0.341) and siderophore (r = -0.199) production (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Correlation map showing the relationship between nutrient mobilization and growth hormone production among the soil yeasts

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis was employed to determine the correlation between soil properties and yeast isolates in the rhizosphere soil (Table 4). The first three eigenvectors (with eigenvalues greater than 1) were considered to constitute the minimum data set of principal components for explaining the maximum significant variation in the investigated variables. According to the PCA, all 3 selected PCs accounted for 69.06% of the total variation.

Table (4):

Principal component analysis with varimax rotation

Factors |

PC1 |

PC2 |

PC3 |

|---|---|---|---|

Eigenvalue |

1.905 |

1.370 |

1.175 |

% of Variance |

28.058 |

21.430 |

19.579 |

Cumulative variance |

28.058 |

49.488 |

69.067 |

P solubilization (%) |

0.657 |

-0.473 |

0.179 |

Zn solubilization (%) |

-0.065 |

0.050 |

0.939 |

K releasing potential (%) |

0.587 |

-0.259 |

0.538 |

IAA Production (µg mL-1) |

-0.139 |

0.823 |

0.279 |

GA3 Production (µg mL-1) |

-0.877 |

-0.252 |

0.269 |

Siderophore production (%) |

0.061 |

0.663 |

-0.223 |

Bold-faced values are highly weighted factors

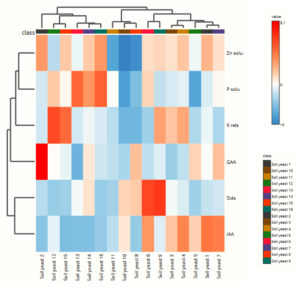

PC1 accounted for 28.0% of the total variance, and PC2 contributed 21.4% to the variance (Figure 6). This finding supports the strong relationship between P and Zn solubilization and the plant growth-promoting potential of yeast isolates. The highly weighted variables in PC1 were P solubilization (%) and K release potential (%), which showed more than 50% variation. High associations with other soil biological indicators make PC1 a strong variable that determines the function of yeast isolates. PC2 was labelled IAA and siderophore production, whereas in PC3, the highly weighted variable was the Zn solubilizing nature of the yeast. PCA revealed that the yeast isolates were differentially correlated with various soil properties that were studied.

Figure 6. Principal component analysis (PCA) of the plant growth promotion traits of 16 yeasts isolated from different ecosystems

Heatmap analysis

The heatmap visualized the response of the yeast isolates to the soil properties and revealed positive (red), medium (white), and negative (blue) impacts of the yeast isolates on the soil parameters (Figure 7). The maximum P solubilizing potential was observed in SY13, SY16, and the reference strain, which are indicated by red patches, whereas the minimum values recorded in SY10 and SY5 are indicated by blue patches. The heatmap-based clustering analysis divided the sixteen yeast isolates into seven clusters. Cluster 1 included only SY2. Cluster 1 included SY12 and SY15, which indicates that these isolates play a substantial role in solubilizing nutrients. Cluster 3 consisted of SY16, SY14, and SY13, whereas SY10, SY11 and SY8 belonged to cluster 4. SY6 and SY9 were distributed in cluster 5. Cluster 6 included SY4 and SY3. Yeast isolates SY1, SY5 and SY7 were classified under cluster 7.

A total of 61 soil yeasts were isolated in the current investigation from soil samples of diverse soil ecosystems such as dryland, wetland, gardenland, saline, and forest soils, by adopting the isolation methodology of Yarrow.33 As this method of isolation includes selective media and antibiotics to supress bacterial growth thereby maximizing the recovery of yeast. Based on their colony characteristics, cellular morphology, and microscopic examination, the isolates were identified. Following the incubation period, colonies that were milky in color and did not exhibit a shiny appearance were purified and preserved for subsequent investigations. Yeast identity was confirmed for sixteen of these isolates by molecular characterization. The 18S rRNA gene is widely used for molecular characterization of yeast because of its conserved and variable sections, which allow both universal amplification and species-specific identification. Its appropriate length and the availability of universal primers make it a viable option for consistent and reliable sequencing. Despite limits in differentiating closely related species, 18S rRNA is nevertheless a valuable tool in yeast taxonomy and phylogenetics.34

Based on the available literature, it is evident that the mean yeast population in agricultural soils was approximately 1.12 × 103 CFU/g, whereas in forest soils, it was approximately 1.4 × 104 CFU/g.35 According to Yarrow, the yeasts were not suppressed by high concentrations of undissociated acids in the medium; therefore, an identical procedure was utilized to isolate the soil yeasts. Based on the findings of the current investigation, it is apparent that yeast isolates are more pervasive in orchard soil. This finding is in agreement with the results reported by Phaff et al.,36 who reported that yeasts are more prevalent and abundant in soils in the vicinity of fruit-bearing trees.

The current study revealed that of the sixteen yeast isolates that were examined, fifteen exhibited the capacity to dissolve inorganic phosphate, and among 15, SY16 showed the highest P solubilization efficacy (59.77 ± 4.18%), which was comparable to that of the reference strain (Pb1) (57.18 ± 4.00%). Zinc solubilization was detected in 13 isolates. Although fourteen isolates can release potassium, their efficacy is significantly inferior to that of phosphorous and zinc solubilization. The potassium release efficacy was comparable between one isolate (SY12, 58.33 ± 4.08%) and the reference strain (KRB 9, 59.25 ± 4.15%).

The yeast Yarrowia lipolytica can solubilize rock phosphate.37 In addition, Vassileva et al.37 and Alonso et al.38 studied several other yeast strains for their capacity to dissolve insoluble inorganic P sources, such as rock phosphates, calcium, and iron. Amprayn et al.39 reported that Candida tropicalis HY exhibited the greatest ability to solubilize P, with a value of 119 ± 10 g mL-1. Hesham and Mohamed40 examined the solubility of phosphorous in yeast isolates. Alonso et al.38 reported that yeasts such as Rhodotorula and Cryptococcus are capable of solubilizing phosphate. Their study disclosed the initial report on the zinc solubilization and potassium release capabilities of soil yeasts, as no earlier research has documented these properties. The findings indicate that 94% of the isolates demonstrated the ability to solubilize P, 81% demonstrated solubilization potential for Zn, and 88% demonstrated potassium release potential.

The current investigation revealed that all sixteen isolates exhibited favourable outcomes in terms of IAA production. SY1 yeast isolates demonstrated the highest level of IAA production among all the isolates (35.42 ± 2.48 µg mL-1). This represents the highest reported IAA production by yeast isolates to date. This is in accordance with the findings of Shih et al.,18 who indicated that yeasts that promote plant growth can generate IAA. Amprayn et al.39 reported the ability of Candida tropicalis HY, a soil yeast, to produce IAAs and further suggested that IAA production gradually increased with time. In addition, the ability of endophytic yeast to produce IAA, the primary group of auxin, has been documented.8 Correlation analysis of the plant growth-promoting traits of soil yeasts indicated that the P solubilization efficiency of soil yeasts was negatively correlated with the ability to produce IAA (r = -0.404), GA (r = -0.341), and siderophores (r = -0.199).

Pandya and Desai41 reported that giberellins from growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) improved the growth and yield of several crops. According to the findings of the present study, gibberellic acid was produced by each of the sixteen yeast isolates, and isolate SY2 was identified as the primary producer. According to a study by Twfiq,9 baker’s yeast is capable of producing GA3. GA3 was produced at concentrations of 6.15, 4.54, and 7.67 µg ml-1 by the yeast isolates Trichosporon asahii, Candida valida, and Rhodotorula sp., respectively.42 Since gibberellic acid production is an important characteristic of plant growth-promoting microbes and, from these studies, yeast shows GA-producing capability, it is evident that soil yeasts may serve as potential plant growth-promoting yeasts (PGPY). However, GA production was negatively correlated with P solubilization (r = -0.341) and the K release potential (r = -0.272), whereas a positive correlation was obtained with Zn solubilization (r = 0.295). Heatmap analysis indicated that the nutrient solubilization potentials of two yeast isolates, SY12 and SY15, were comparable to those of the reference strains used.

Plant growth is enhanced by microorganisms that produce siderophores by increasing the availability of iron near roots or by inhibiting the colonization of roots by plant pathogens or other detrimental bacteria.43 According to the findings of our present study, all the isolates produced siderophores in significant quantities. Overall, SY9 showed increased siderophore production (65.95 ± 4.62%), five isolates showed weak siderophore production, and the remaining isolates produced a considerable amount of siderophores. This discovery is consistent with a prior investigation carried out by Calvente.3 The author stated that Rhodotorula strains generate rhodotorulic acid, which accounts for 60% of siderophores, and yeasts generate hydroxamate-type siderophores (iron-binding compounds) in reaction to Fe stress conditions. These siderophores play a crucial role in the biocontrol of postharvest diseases affecting apple and pear crops. According to Verma et al.,44 the iron-transport capabilities of siderophores are crucial for facilitating plant growth and inhibiting the impact of plant pathogens. The findings of this study indicate that the chosen soil yeasts can generate siderophores, which consequently have the potential to facilitate plant development and mitigate the proliferation of plant pathogens to a certain extent.

The only yeast isolate among the sixteen strains that produced HCN was SY4, as determined by the picric acid solution assay. Hydrogen cyanide, a potent antifungal compound produced by PGPR, is utilized in biological control.45 This finding supports our finding that the yeast isolate SY4 could be utilized as a biocontrol agent.

Principal component analysis of the plant growth-promoting traits revealed a clear separation of the 16 yeast isolates collected from 3 different ecosystems, explaining 69% of the total variation (Figure 1). The main variables explaining this separation were P solubilization (%) and K release potential (%) with higher values in fields from the orchard and garden lands, whereas Zn solubilization (%) was greater in garden land fields located in Thondi. Component two accounted for 21% of the total variation and was associated mainly with GAA production, which was greater in yeasts isolated from black gram soil of garden land fields in Thondi, whereas IAA was associated with SY1. The heatmap analysis effectively distinguished the plant growth-promoting capabilities of the studied strains and clustered them into seven distinct groups.

At present, the use of biocontrol agents to manage disease has been explored as an effective alternative to synthetic chemicals. The additional discovery of novel antagonists is preferable due to the enhanced efficacy of antagonists identified in particular geographic regions against the strains of pathogens prevalent in that area.46 The current study revealed that the antimicrobial efficacy of soil yeasts against the soil-dwelling pathogen Pythium sp. Pythium sp. was effectively inhibited by the yeast isolate SY4, which exhibited an inhibition zone measuring 4.1 mm in diameter. El-Tarabily42 reported that the combined use of three yeast species, C. valida, R. glutinis, and T. asahii, produced significant biocontrol activity against sugar beet diseases caused by Rhizoctonia solani, including damping off and crown and root rot. The production of cell wall-degrading enzymes by yeast isolates is regarded as one of the most advantageous biocontrol mechanisms. Consistent with these earlier reports, the findings of the current investigation demonstrate that soil yeast has the potential to function as a biocontrol agent in the management of plant diseases.

The findings of the current investigation have illuminated the latent capacity of soil yeasts to serve as potential inoculants for enhancing plant growth. Research on soil yeasts in India is still in its nonage phase, with soil yeasts continuing to be utilized as an unidentified component in microbial inoculants. The current study proved the potential of soil yeasts as diverse plant growth promoters. Sixteen of the sixty-one isolates obtained were validated as yeasts through molecular analysis with 18S rRNA sequencing. These isolates demonstrated a wide range of plant growth-promoting (PGP) properties, including inorganic nutrient solubilization, phytohormone production, siderophore synthesis, and resistance to soil-borne diseases. Notably, isolates SY16, SY13, and SY12 displayed superior phosphate, zinc, and potassium solubilization efficiency, whereas SY1, SY2, and SY8 produced large levels of IAA and gibberellic acid. SY9 and SY6 were powerful siderophore makers, while SY4 produced HCN and had antagonistic action against Pythium sp., suggesting a dual involvement in nutrient mobilization and pathogen suppression. Correlation and principal component studies revealed significant relationships between important nutrient-solubilizing and hormone-producing traits, underlining the metabolic interdependence of these mechanisms. Heatmap analysis revealed a significant clustering pattern among isolates, highlighting the presence of distinct yeast groups with particular growth-promoting qualities. Further investigation into the impact of soil yeasts on promoting plant growth via pot culture and field trials will lead to the identification of a viable yeast candidate that can be utilized for sustaining the production of crop plants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful to Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF), Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, for the technical support rendered through the project entitled “Development of yeast inoculant for soil and plant health improvement and drought mitigation (SUR/2022/001739)”. The authors also like to acknowledge Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India, for providing research facilities to conduct this research programme.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

RPD, PY, KS, and DB conceptualized the study. RPD, PY, KS, and SV applied methodology. KS, DUN, and SV performed software work. RPD, PY, KS, DB, DUN, SV, and DR collected resources, performed data curation, investigation, formal analysis, visualization and validation. RPD, KS, DUN, and SV wrote the manuscript. RPD, DB, and DR performed supervision. RPD, PY, KS, DB, DUN, SV, and DR reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Ekelund F, Ronn R, Christensen S. Distribution with depth of protozoa, bacteria and fungi in soil profiles from three Danish forest sites. Soil Biol Biochem. 2001;33(4-5):475-481.

Crossref - Yamunasri P, Manikandan A, Balachandar D, et al. Microbial Inoculants-A Boon to Overcome the Challenges of Soil Problems. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2025;56(8):1272-1290.

Crossref - Calvente V, de Orellano ME, Sansone G, Benuzzi D, De Tosetti MIS. A simple agar plate assay for screening siderophore producer yeasts. J Microbiol Methods. 2001;47(3):273-279.

Crossref - Sampedro I, Aranda E, Scervino GM, et al. Improvement by soil yeasts of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis of soybean (Glycine max) colonized by Glomus mosseae. Mycorrhiza. 2004;14(4):229-234.

Crossref - Vogel K, Hinnen A. The yeast phosphatase system. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4(12):3-7.

Crossref - Ramya P, Gomathi V, Devi P, Balachandar D. Isolation and screening of soil yeasts for plant growth promoting traits. Madras Agric J. 2019;106(7-9).

Crossref - Falih AM, Wainwright M. Nitrification, S-oxidation and P-solubilization by the soil yeast Williopsis californica and by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mycol Res. 1995;99(2):2-4.

Crossref - Spaepen S, Vanderleyden J, Remans R. Indole-3-acetic acid in microbial and microorganism-plant signalling. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2007, 31(4):425-448.

Crossref - Twfiq AA, Al-Shaheen MR, Farhan MA, Al-Shaheen MR. The possibility of cytokinins production from regular dry bakery yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Int J Recent Innov Food Sci Nutr. 2018;1(1):1-4.

- Devi RP, Yamunasri P, Balachandar D, Murugananthi D. Potentials of Soil Yeasts for Plant Growth and Soil Health in Agriculture: A Review. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2025;19(1):1-18.

Crossref - Ramya P, Gomathi V, Devi P, Balachandar D. Pichia kudriavzevii a potential soil yeast candidate for improving soil physical, chemical and biological properties. Arch Microbiol. 2021:203.

Crossref - Agamy R, Hashem M, Alamri S. Effect of soil amendment with yeasts as biofertilizers on the growth and productivity of sugar beet. Afr J Agric Res. 2013;8(1):46-56.

- Kumutha K, Devi RP, Marimuthu P, Krishnamoorthy R. Shelf Life Studies of Seed Coat Formulation of Rhizobium and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus (AMF) for Pulses – A New Perspective in Biofertilizer Technology. Indian J Agric Res. 2023;57(1):89-94.

Crossref - Devi RP, Gnanachitra M, Marimuthu S. Studies on combined application of bacterial and fungal bioinoculants on growth and yield of blackgram. Journal of Food Legumes. 2024;35(4):305-308.

- Ramalakshmi, A, Devi RP. Performance Evaluation of Co-Inoculation of Rhizobium, Phosphobacteria and AM Fungi in Greengram var Paiyur1. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2018;7(05):3726-3730.

Crossref - Abd El-Hafez AE. Field evaluation of yeasts as a biofertilizer for some vegetable crops. Arab Universities J Agric Sci. 2001;9:169-182.

- Edi-Premono M, Moawad A, Vlek P. Effect of phosphate-solubilizing Pseudomonas putida on the growth of maize and its survival in the rhizosphere. Indonesian Journal of Crop Science. 1996;11:13-23.

- Shih PM, Vuu K, Mansoori N, et al. A robust gene-stacking method utilizing yeast assembly for plant synthetic biology. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13215.

Crossref - Viana AR, Noro BG, Santos D, et al. Detection of new phytochemical compounds from Vassobia breviflora (Sendtn.) Hunz: Antioxidant, cytotoxic and antibacterial activity of the hexane extract. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2022;86(2-3):51-68.

Crossref - Chen J, Luo Y, Xia J, et al. Stronger warming effects on microbial abundances in colder regions. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18032.

Crossref - Scherer S, Stevens DA. Application of DNA typing methods to epidemiology and taxonomy of Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25(4):675-679.

Crossref - Pinjon E, Sullivan D, Salkin I, Shanley D, Coleman D. Simple, Inexpensive, Reliable Method for Differentiation of Candida dubliniensis from Candida albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36(7):2093-2095.

Crossref - Harju S, Fedosyuk H, Peterson KR. Rapid isolation of yeast genomic DNA: Bust n’Grab. BMC Biotechnol. 2004;4(1):8.

Crossref - Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual (2nd eds)Cold spring harbor laboratory press. 1989.

- Sperber JI. Release of phosphate from soil minerals by hydrogen sulfide. Nature. 1958;181;934.

Crossref - Bunt JS, Rovira AD. Microbiological studies of some subantartic soils. J Soil Sci. 1955;6(1):119-128.

Crossref - Aleksandrov VG, Blagodyr RN, Ilev IP. Liberation of phosphoric acid from apatite by silicate bacteria. Mikrobiolz. 1967;29:111-114.

- Gordon SA, Weber RP. Colorimetric estimation of indoleacetic acid. Plant Physiol. 1951;26(1):192.

Crossref - Mahadevan A, Sridhar R. Methods in physiological plant pathology. 2nd eds, Sivakami Publications, Madras, 1982. OCLC Number/Unique Identifier:475771748

- Schwyn B, Neilands JB. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem. 1987;160(1):47-56.

Crossref - Higgins VJ, Millar R. Degradation of alfalfa phytoalexin by Stemphylium loti and Colletotrichum phomoides. Phytopathology. 1970;60:269-271.

Crossref - Wisniewski M, Biles C, Droby S, McLaughlin R, Wilson C, Chalutz E. Mode of action of the postharvest biocontrol yeast, Pichia guilliermondii. I. Characterization of attachment to Botrytis cinerea. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1991;39(4):245-258.

Crossref - Yarrow D. Methods for the isolation, maintenance and identification of yeasts. In: Kurtzman CP, Fel JW. eds. The Yeasts. 1998:77-100.

Crossref - Yarza P, Yilmaz P, Panzer K, Glockner FO, Reich M. A phylogenetic framework for the kingdom Fungi based on 18S rRNA gene sequences. Marine Genomics. 2017;36:33-39.

Crossref - Slavikova E, Vadkertiova R. The occurrence of yeasts in the forest soils. J Basic Microbiol. 2000;40(3):207-212.

Crossref - Phaff HJ, Miller MW, Mrak EM. The life of yeasts: Their nature, activity, ecology, and relation to mankind. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard Univ. Press. 1966. ISBN0674863550, 9780674863552.

- Vassileva M, Azcon R, Barea JM, Vassilev N. Rock phosphate solubilization by free and encapsulated cells of Yarrowia lipolytica. Process Biochem. 2000;35(7):693-697.

Crossref - Alonso LM, Kleiner D, Ortega E. Spores of the mycorrhizal fungus Glomus mosseae host yeasts that solubilize phosphate and accumulate polyphosphates. Mycorrhiza. 2008;18(4):197-204.

Crossref - Amprayn KO, Rose MT, Kecskes M, Pereg L, Nguyen HT Kennedy IR. Plant growth promoting characteristics of soil yeast (Candida tropicalis HY) and its effectiveness for promoting rice growth. Appl Soil Ecol. 2012;61:295-299.

Crossref - Hesham AEL, Mohamed HM. Molecular genetic identification of yeast strains isolated from Egyptian soils for solubilization of inorganic phosphates and growth promotion of corn plants. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;21(1):55-61.

Crossref - Pandya ND, Desai PV. Screening and characterization of GA3 producing Pseudomonas monteilii and its impact on plant growth promotion. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2014;3(5):110-115.

- El Tarabily KA. Suppression of Rhizoctonia solani diseases of sugar beet by antagonistic and plant growth promoting yeasts. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;96(1):69-75.

Crossref - Alexander DB, Zuberer DA. Use of chrome azurol S reagents to evaluate siderophore production by rhizosphere bacteria. Biol Fert Soils. 1991;12(1):39-45.

Crossref - Verma VC, Singh SK, Prakash S. Bio control and plant growth promotion potential of siderophore producing endophytic Streptomyces from Azadirachta indica A. Juss. J Basic Microbiol. 2011;51(5):550-556.

Crossref - Haas D, Defago G. Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent pseudomonads. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(4):307.

Crossref - Wilson CL, Wisniewski ME. Biological control of postharvest diseases of fruits and vegetables: an emerging technology. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1989;27(1):425-441.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.