ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Intercropping and fertilization practices are increasingly promoted as ecological alternatives to improve soil health and crop productivity. This work examined their combined effects on soil microbial communities and onion yield over two growing seasons. The aim of this study was to assess how different intercropping systems combined with organic and mineral fertilization influence soil microbial communities and onion performance. Treatments included onion monoculture and intercropping with carrot, pepper or fennel, under compost and NPK fertilization, arranged in a randomized block design. Soil analyses focused on bacterial, fungal and actinomycetes loads, microbial biomass carbon (MBC), and their relationship with onion yield. Results indicated that growing season, fertilization, and intercropping, as well as their interactions, had significant effects on all microbial parameters and yield (p < 0.001). Compost application led to the highest microbial stimulation, increasing bacterial populations by 42%, fungal counts by 33%, actinomycetes by 45%, and MBC by 32%, compared to the unfertilized control. Carrot intercropping further enhanced soil activity, raising actinomycetes by 48% and MBC by 35%. This cropping system also improved onion performance, with yield rising from 2.5 kg/plant in the control to 5.4 kg/plant under compost treatments and 5.1 kg/plant with carrot intercropping, highlighting the positive link between microbial enhancement and productivity. Moderate positive correlations were observed between microbial parameters and yield, particularly for bacteria (R² = 0.27) and actinomycetes (R² = 0.20). These findings emphasize the potential of integrating organic fertilization with strategic intercropping to enhance soil biological functioning and promote sustainable onion production.

Ecological Intensification, Crop Productivity, Compost Amendment, Rhizospheric Microbial Community, Agroecological Practices

In Morocco, Onion (Allium cepa L.) ranks second after potato in economic importance.1 However, onions shallow and sparsely branched roots make it highly vulnerable to nutrient deficiencies, necessitating careful soil fertility management.2 With growing demands on arable land due to population growth and resource scarcity, onion production is often based on monoculture and conventional tillage practices, which can accelerate soil erosion, reduce soil fertility, and contribute to long-term soil degradation, ultimately limiting the sustainability and ecological value of onion cultivation.1,3,4 Farming systems are under increasing pressure to adopt methods that maximize output without compromising ecological integrity.5 In this context, integrated cropping systems have emerged as a promising solution, aiming to optimize solar energy use while preserving soil fertility, maintaining ecosystem health, and promoting biodiversity.6-8 Compared to conventional monoculture, diversified systems such as intercropping represent a more holistic and sustainable approach to agriculture,1,5 with transformative applications in horticulture and agro-industry.9-11

Intercropping is the simultaneous cultivation of two or more crops or species in the same field. It is increasingly regarded as an agroecological practice for sustainable intensification.5,8,12 Historically, it has been adopted to boost productivity,13-15 improve land-use efficiency,16,17 and reduce environmental risks.18,19 One of its lesser-known but highly valuable outcomes is its impact on the soil microbiome. 20-22 Microbial communities are essential for key processes like organic matter decomposition, nutrient cycling, and plant development.23-25 Microbial biomass carbon (MBC), in particular, serves as a strong indicator of soil health, contributing significantly to nutrient availability, soil aggregation, and carbon storage.26,27

Organic fertilizers such as compost are being used to improve productivity, soil structure and health, nutrient content, and biological activity.2,28 Compost contributes not only to plant nutrition but also to microbial stimulation and soil carbon stabilization29 due to its porosity, surface area, and humic substance content.30

Various tools have been developed to assess microbial communities and biomass, including culture-based plate counting,31 phospholipid fatty acid analysis,32 chloroform fumigation extraction,33 and DNA-based methods.34 According to Mangla et al.35 plate counting remains widely used for its accuracy in estimating viable microbial populations through colony forming units (CFU), offering a clear picture of culturable microbes.

Studies have increasingly shown that intercropping promotes microbial biomass and activity in the rhizosphere, enhancing yield, nutrient cycling and ecosystem resilience.22,36 For example, sugarcane-peanut intercropping has been shown to improve enzymatic activity and microbial diversity,37 while lily-maize combinations enriched beneficial bacteria in the rhizosphere.38 Similar trends were observed in proso millet-mung bean systems, which supported diverse bacterial and fungal communities and improved yield.39 Organic amendments have demonstrated strong potential as substitutes for mineral fertilizers, offering improved microbial activity and soil health.23,24,40,41 Compost has also been shown to significantly influence microbial community structure and function across agroecosystems.11,42

However previous studies have primarily focused on the effects of either organic amendments or intercropping systems as single factors on soil microbial dynamics.43-45 For instance, compost has been shown to improve microbial activity and carbon sequestration, while intercropping has been linked to increased microbial diversity and root-microbe interactions.36,46 However, research addressing the synergistic impact of combining organic fertilization with intercropping, particularly in onion-based systems, remains scarce. The main objective of this study is to assess the effects of onion intercropping with pepper (Capsicum annuum), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) and carrot (Daucus carota), combined with either organic (compost) or chemical (NPK) fertilization on soil microbial biomass carbon and the densities of bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes. The study also aims to evaluate how these agroecological strategies affect onion yield, in order to identify productive and biologically enriched cropping systems that enhance soil fertility and promote sustainable vegetable production.

Geographical location and description of the field site

Field experiments related to the study were carried out in the AGREE platform (AGREE = Agroecology and Environment) of National School of Agriculture in Meknes (33°502 363 N 5°282 393 W and 546 m above sea level), during two consecutive growing seasons (2020-2021) and (2021-2022). According to the Koppen-Geiger classification, the climate of the experimental area is typically a warm temperate Mediterranean climate and the rainfall and average annual temperature in the area are 511 mm and 19.2 °C, respectively. To assess the physicochemical attributes of the soil, two samples were gathered from depths ranging from 0-30 cm using the Z sampling technique.47 Following the collection, the samples underwent sieving and were then sent to the Labomag soil analysis laboratory located in Meknes, Morocco. The soil texture at the site is loam clay sand. Soil characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Table (1):

Physical and chemical characteristics of the soil (depth: 0-30 cm) before sowing, in the first (2020-2021) and second (2021-2022) growing seasons

| Soil property | First growing season (2020-2021) | Second growing season (2021-2022) |

|---|---|---|

| Texture | Clay loam sand | |

| Organic matter (%) | 2.76 | 2.77 |

| pH | 8.5 | 8.6 |

| Electrical conductivity(ms/cm) | 0.17 | 0.06 |

| N-NH4 | 0.15 | 1.98 |

| MgO (mg/kg) | 2297.5 | 918.1 |

| P (mg/kg) | 45 | 63.4 |

| K (mg/kg) | 280.5 | 104.9 |

| Na2O (mg/kg) | 196.5 | 221.9 |

| CaO (mg/kg) | 10470.5 | 9000 |

Cropping system, intercultural operations and fertilizer application

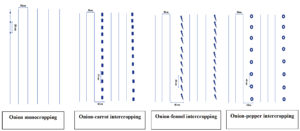

The experiment was arranged in a factorial complete block design involving three factors: cropping system (onion monoculture or intercropping), fertilization type (mineral, organic, or control), and growing seasons (2020-2021 and 2021-2022). The trial area covered approximately 9372 and was divided into three blocks, each 4.5 meters wide and spaced 1.5 meters apart (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the different cropping systems used in the field experiment: onion monocropping (20 x 30 cm), onion-carrot (25 x 30 cm), onion-fennel (20 x 60 cm) and onion-pepper (40 x 45 cm). Each intercropping system followed a 3:1 ratio (three rows of onion to one row of intercrop)

The field experiment was structured into blocks, each containing 12 elementary plots corresponding to different cropping treatments (Table 2). Each plot measured 4.5 meters wide by 4 meters long, with 0.80 meter spacing between them to prevent overlap of crop influence. In each plot, onions were either grown alone or intercropped with carrot, fennel, or pepper, following a 3:1 ratio of onions to the intercrop (Figure 1). To reduce edge effects, two additional rows of onions were planted around the perimeter of each plot. Crops were manually sown in April of both the 2021 and 2022 seasons. The planting layout followed specific intra and inter-row spacings tailored to each crop growth needs: 20 × 30 cm for onion transplants, 25 × 30 cm for carrot seeds, 20 × 60 cm for fennel seeds, and 40 × 45 cm for pepper. Throughout the growing seasons, the crops were maintained under typical field conditions. Irrigation was provided for 1 hour/day, and weeds were removed manually. Pest management was carried out as needed, depending on crop sensitivity and field observations. Fertilization followed local farming practices in the Fez-Meknes region. Compost was used as organic fertilizer at a rate of 36 kg per plot, split into two applications once after sowing and one post-seed emergence. Chemical fertilization consisted in a synthetic NPK fertilizer (10:30:20) which was used at 2 kg per plot for onion monoculture and 2.5 kg per plot for the intercropped systems. Onion bulbs were harvested in mid-August, when 80% of onion leaves had naturally fallen over. The mature bulbs were manually pulled and left to dry in the sun for 15 days before measuring yield.

Table (2):

Number of rows in each cropping system and description of the different treatments contained therein

Cropping systems (CS) |

Code |

Treatment Description |

Number of rows |

|---|---|---|---|

CS1 |

On |

Onion sole crop |

8 |

CS2 |

OnI |

Onion + NPK fertilizer |

8 |

CS3 |

OnO |

Onion + Compost amendment |

8 |

CS4 |

OnP |

Onion + Pepper (3:1) |

8 |

CS5 |

OnPI |

Onion + Pepper + NPK fertilizer (3:1) |

8 |

CS6 |

OnPO |

Onion + Pepper + Compost amendment (3:1) |

8 |

CS7 |

OnF |

Onion + Fennel (3:1) |

8 |

CS8 |

OnFI |

Onion + Fennel + NPK fertilizer (3:1) |

8 |

CS9 |

OnFO |

Onion + Fennel + Compost amendment (3:1) |

8 |

CS10 |

OnC |

Onion + Carrot (3:1) |

8 |

CS11 |

OnCI |

Onion + Carrot + NPK fertilizer (3:1) |

8 |

CS12 |

OnCO |

Onion + Carrot + Compost amendment (3:1) |

8 |

Soil sampling, method protocol and analytical studies

Soil samples were collected from each treatment in T0 (before sowing), T1 (53 days after sowing DAS), T2 (96 DAS) and after harvest Tf (134 DAS). During the sampling process, sterile paper was used to wipe the remains that were attached to the spade and sanitize the spade before collecting the next soil sample to avoid contamination between treatments and keep samples fresh. The samples (about 200 g) were collected at 0-15 cm soil depths using an auger of 5 cm diameter in the rhizosphere of onion, were then put in sterile plastic bags and transported to the laboratory. The soil samples were air-dried in the shade, ground to pass through a 2 mm sieve and were also stored at 4 °C for the enumeration of cultivable microbial indicators.

Microbial biomass carbon

Microbial biomass carbon was measured utilizing the fumigation extraction method as described by Vance et al.48 Five sets of 10 g soil samples were carefully weighed and fumigated with ethanol-free chloroform for 24 h and extracted with 40 mL of 0.5 M K2SO4. The extracts were oxidized with potassium dichromate and sulfuric acid and titrated with ferrous ammonium sulfate. MBC was calculated as the difference in extractable carbon between fumigated and non-fumigated samples.

Organic C % = (Vb – Vs) × 0.003 × N × 100 / Ws

Where:

VS = Volume of 0.2 N [Fe (NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O] titrated for the sample (mL)

VB = Digested blank titration volume (mL)

N = Normality of [Fe (NH4)2(SO4)2·6H2O] solution = 0.005N

0.003 = 3 × 10-3, where 3 is equivalent weight of C

Ws = Weight sample (10 g)

Bioassay of microbial community

To assess the cultivable microbial communities in rhizosphere soils, the colony forming units (CFUs) were quantified using a plate count method. Each soil sample underwent analysis in triplicate. Pure and viable microbial counts were obtained through a serial dilution technique on nutrient agar medium. Soil samples (n = 36) were collected before sowing, 53 days after sowing (DAS), 96 days after sowing (DAS), and post-harvest (134 DAS). For each soil sample, 10 g was mixed with 90 ml of sterile distilled water. After homogenization for 30 minutes, the resulting mother solution was diluted from 10-1 to 10-5, and aliquots (100 µl) of the resulting dilutions were spread onto appropriate culture media.49 Following bacterial incubation on LPGa medium,50 fungal growth on PDA medium,51 and actinomycetes on Kuster medium,52 the colony-forming unit (CFU) was determined after days of incubation at 20 °C and was expressed per gram (g-1) of dry soil.

CFU/g dry soil = Number of colonies × Dilution factor / Volume plated (mL) × Dry weight of soil (g)

Statistics

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used in the study to diagnose the effect of factors separately and in combination on soil traits.53 Pearson’s correlation test was carried out to investigate the possible associations between yield and microbiological traits.54 Principal component analysis (PCA) was used as a multivariate test in the aim of evaluating relationships between soil traits and treatments.55 All tests made in the study were carried out using XLStat software.

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) conducted in this study provided a comprehensive assessment of the effects of each factor and their interactions on the variability of microbiological traits and onion yield (Table 3). The three factors growing season, fertilizer, and intercropping as well as their interactions, significantly influenced the variability of all traits measured in the study. For bacterial and actinomycetes counts, the growing season emerged as the primary source of variability, followed by intercropping and fertilizer factors. In the case of microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and fungal counts, intercropping was identified as the principal source of variability, followed by growing season and fertilizer factors. Conversely, the main source of variability in onion yield was the fertilizer factor, followed by intercropping and growing season factors (Table 3).

Table (3):

Mean squares of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the microbial characteristics evaluated (bacteria, fungi, actinomycetes and microbial biomass carbon MBC) and yield in onion in the different cropping systems

Source of variability |

Df |

Bacteria |

Fungi |

Actino |

MBC |

Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Replicate |

2 |

4.13E+07 |

5.66E+01 |

4.39E+08 |

2650 |

0.04 |

Year (Y) |

1 |

3.48E+10*** |

1.03E+04*** |

3.71E+11*** |

20571*** |

0.63*** |

Fertilizer (F) |

3 |

2.86E+10*** |

7.23E+03*** |

8.98E+10*** |

29971*** |

12.30*** |

Intercropping (I) |

3 |

1.43E+10*** |

1.17E+04*** |

1.99E+11*** |

161875*** |

7.83*** |

Y*F |

3 |

6.38E+08*** |

7.06E+02*** |

4.53E+10*** |

5465** |

0.12*** |

Y*I |

3 |

1.54E+09*** |

5.41E+02*** |

7.59E+10*** |

3645* |

0.28*** |

F*I |

9 |

9.61E+08*** |

6.40E+02*** |

7.84E+09*** |

2725** |

0.24*** |

Y*F*I |

9 |

6.82E+08*** |

2.68E+02*** |

7.95E+09*** |

1548 |

0.03*** |

Error |

38 |

3.57E+07 |

3.63E+01 |

1.22E+08 |

860 |

0.00 |

Total |

71 |

Df: Degree of freedom; *: significant at 0.05; **: significant at 0.01; ***: significant at 0.005; Actino: Actinomycetes; MBC: Microbial biomass Carbon

Means comparison

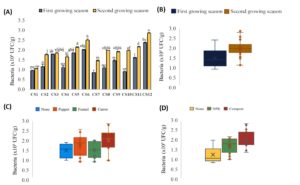

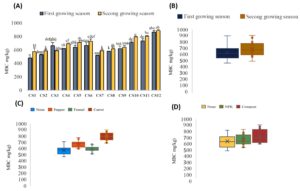

The variation in rhizospheric bacterial counts across the 12 different cropping systems are shown in Figure 2. The lowest bacterial count (about 1.05 × 105 CFU/g) was reported in Cs1 (On) for both growing seasons, and in Cs2 (OnI), Cs4 (OnP), Cs7 (OnF), Cs8 (OnFI), and Cs10 (OnC) during the first growing season (Figure 2a). The highest bacterial counts were recorded in Cs12 (OnCO) in both the first and second growing seasons, with 2.5 × 105 and 3 × 105, respectively, followed by Cs6 (OnPO) with 2 × 105 and 2.5 × 105 in the first and second growing seasons, respectively, and Cs5 (OnPI) with 1.9 × 105 and 2.3 × 105 (Figure 2a). Figure 2b, showing the effect of the growing season on bacterial count variability, recorded a significant bacterial count increase in the second growing season by around 30% compared to the first. Regarding the intercropping factor manifested in Figure 2c, carrots showed the highest significant increase (27%) compared to the control (without intercropping = None). For the fertilizer factor (Figure 2d), a significant increase in bacterial count was reported in the case of NP Regarding actinomycete counts K and organic fertilization (compost) when compared to the control (no fertilizer added). Organic fertilizer showed a high bacterial count increase (42%) compared to NPK (35%).

Figure 2. Variation in rhizospheric bacterial counts across the 12 cropping systems under this study. The results are presented both as combined factors (A) and as individual factors: Growing season (B), intercropping (C) and fertilization (D)

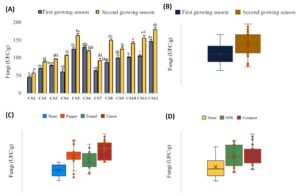

Figure 3. Variability in fungi counts for each cropping system studied (A) and the effect of each factor: Growing season (B), intercropping (C) and fertilization (D)

Cs1 (On) in both growing seasons recorded the lowest scores (⁓50 CFU/g). The highest scores were reported in the second growing season for Cs12 (OnCO) (⁓180 CFU/g), Cs5 (OnPI), Cs11 (OnCI), and Cs8 (OnFI) (⁓160 CFU/g) (Figure 3a). Regarding the effect of the growing season factor, fungi counts in the second growing season were around 25% higher than in the first season (Figure 3b). For the intercropping factor, all three intercropping systems showed higher fungi counts than the onion culture without intercropping. The highest fungi count was reported in the carrot intercropping system, with a 53% increase, followed by pepper (40%) and fennel (18%) (Figure 3c). Concerning the fertilization factor, both NPK and organic fertilizers similarly increased fungi counts by around 32% compared to the control (no fertilization) (Figure 3d).

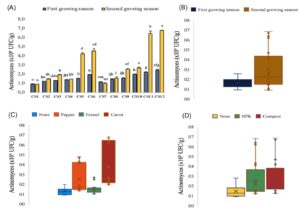

Figure 4. Variability in actinomycetes counts in the different cropping systems studied presented in combined factors (A) and each experimental factor effect: Growing season (B), intercropping (C) and fertilization (D)

Regarding actinomycete counts (Figure 4), the lowest values (around 105 CFU/g) were recorded in Cs1 (On) and Cs7 (OnF) for both growing seasons. The highest scores were reported for Cs12 (OnCO) (7 x 105 CFU/g), Cs11 (OnCI) (6.5 x 105 CFU/g), Cs6 (OnPO) (5 x 105 CFU/g), and Cs5 (OnPI) (4.5 x 105 CFU/g) in the second growing season (Figure 4a). Figure 4b shows a significant increase in actinomycete counts in the second growing season by around 40% compared to the first. For the intercropping factor, when compared to the control, the cropping system OnF had no significant impact. In contrast, carrot and pepper significantly increased actinomycete counts by around 40% and 25%, respectively (Figure 4c). Concerning the fertilization factor, organic fertilizer showed the highest increase in actinomycete counts (40%) compared to the control (Figure 4d).

Regarding MBC trait, the lowest scores were noted in the first growing season of Cs1 (On), Cs2 (OnI), and Cs7 (OnF) (around 500 mg/kg). The highest MBC levels were reported in both growing season of Cs12 (OnCO) (⁓900 mg/kg), Cs11 (OnCI) (⁓780 mg/kg), and Cs10 (OnC) (780 mg/kg) (Figure 5a). The growth season factor seems had not a significant effect on MBC variability (Figure 5b). For intercropping factor, using fennel has not showed any significant difference compared to the control (only onion without intercropping). In contrast, MBC significantly increased in the case of carrot and pepper by around 25% and 15%, respectively (Figure 5c). On the other hand, no significant effect was revealed for fertilization factor (Figure 5d).

Figure 5. Variability in microbial biomass carbon (MBC) across the cropping systems both presented as combined factors (A) and the effects of each factor: growing season (B), intercropping (C) and fertilization (D)

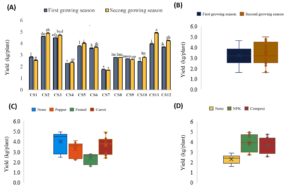

Figure 6. Variability in onion crop yield across different treatments in onion cropping systems. The results are presented both as combined factors (A) and the effects of each factor: growing season (B), intercropping (C) and fertilization (D)

The lowest yields were recorded in Cs7 (OnF), Cs4 (OnP) and Cs1 (On), with values of 1.5, 2.2, and 2.7 kg/plant, respectively (Figure 6a). The growing season had no significant impact on onion yield (Figure 6b). Notably, intercropping with fennel led to a significant reduction in onion yield by 28% compared to the control (Figure 6c). Regarding the fertilization, both NPK and organic fertilizers significantly increased onion yield by approximately 62% relative to the control with no significant difference observed between the two fertilizer treatments (Figure 6d).

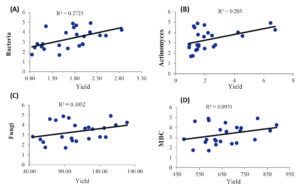

Correlation test

The correlation test (Pearson) showed in Figure 7 revealed the potential association of onion yield production with other microbiological traits. No significant (p ≥ 0.05) correlations recorded for onion yield with fungi count and MBC traits. On the other hand, onion yield correlated positively and significantly with bacteria count (R2 = 0.35*) and actinomycetes count (R2 = 0.29*).

Figure 7. Linear relations between onion yield and microbial parameters across the experimental treatments in onion cropping systems (A) bacteria, (B) actinomyces, (C) fungi, (D) microbial biomass carbon (MBC)

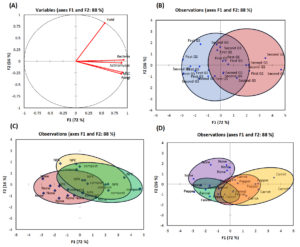

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was adopted in the current study to show the effect of treatments on soil microbiological traits and onion yield (Figure 8). The first two principal components (PC) PC1 and PC2 presents 88% of the total variation, with PC1 accounting for 72% and PC2 for 16%. All traits studied were presented on the positive side of PC1. The associations between soil microbiological traits and onion yield, shown in Figure 8a, revealed high significant association between bacteria and actinomycetes counts and between MBC and fungi count.

Figure 8b shows the distribution of plots of growing season factor, the majority of the second growing season plots are ranked in the positive area of PC1 with high scores of yield and bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes counts, as well as MBC trait, against low value for the first growing season where most of plots are ranked in the negative side of PC1 and near to the axe. For fertilization factor, plots linked to NPK and organic fertilizer are presented in the positive side of PC1 with high scores of onion yield and bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes counts, as well as MBC trait. However, the plots of non-fertilized onion are ranked in the negative side of PC1 with low scores of last traits (Figure 8c). For intercropping factor, the highest effect was recorded in the case of carrot, where the carrot plots are clearly discriminated in the positive side of PC1 with high scores of yield and microbiological traits. In contrast, no discrimination recorded for other crops and control (no intercropping) plots (Figure 8d).

Figure 8. Principal component analysis (PCA) biplot showing relationships between microbial traits (bacteria, actinomycetes, fungi and microbial biomass carbon, MBC) and onion yield across cropping systems and fertilization treatments during the two growing seasons, (A) Variables on F1 and F2 axes, (B) growing season, (C) fertilization treatment, (D) cropping system

In the present study, we aimed to identify the impact of two different agroecological practices, namely organic fertilizer and intercropping patterns, on onion yield, microbial load (bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes), and microbial biomass carbon (MBC), and to reveal the relationships between yield and soil microbial characteristics within the intercropping system.

Effect of intercropping on microbial biomass carbon, microbial load, and yield

Soil microorganisms are essential to soil health, acting as key players in nutrient cycling and overall soil ecosystem functioning. According to Janke et al.41,56 an imbalance in the structure of soil microbial communities can result in reduced crop yields and declining soil quality. Bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes play a central role in breaking down organic matter and supporting plant growth. Their abundance and activity offer valuable insights into dynamic interactions between soil, crops, and microbial communities, especially within intercropping systems.57 In this study, microbial counts varied considerably between intercropping and monoculture systems. Across all treatments, bacterial and actinomycete populations were consistently higher than fungal populations over both growing seasons. This shift from a fungal-dominated to a bacterial-dominated profile suggests an overall improvement in soil biological quality, as bacterial communities are generally associated with faster nutrient cycling, greater enzymatic activity, and enhanced disease suppression.56,58,59 This transition toward a bacterial-type soil is particularly beneficial in systems recovering from soil fatigue caused by continuous monoculture.60 Our results confirm that intercropping enhances microbial characteristics compared to monocropping. Intercropping is a sustainable and efficient agronomic practice involving the simultaneous cultivation of two or more crops or species in the same field.5,57,61 This system improves the use of natural resources (light, water, nutrients, and space) and ultimately enhances crop productivity. In addition to yield benefits, intercropping also improves soil fertility, supports water conservation, reduces pest and disease pressure, and strengthens the resilience of agroecosystems to environmental stresses.5,62 These outcomes are closely attributed to changes in the soil microbiome, which plays a critical role in nutrient cycling, organic matter decomposition, disease suppression, and broader ecosystem functionality.22,62 Increased plant diversity in the root zone can stimulate microbial proliferation through the release of root exudates and improved carbon availability. This is likely due to the increased presence of crop residues in intercropping systems, which support microbial incorporation and organic matter turnover.6 Several studies have reported that intercropping leads to higher microbial biomass carbon (MBC), potentially due to greater root biomass and residue production.6,63-66 Our results align with those of Zhou et al.,67 who found that relay intercropping with garlic improved microbial activity, organic matter breakdown, and nutrient uptake, driven by increased bacterial abundance and a relative reduction in fungal populations. Among the three intercropping systems evaluated, the onion-carrot system emerged as the most effective, resulting in significantly higher MBC and microbial counts than either the control or the other intercropping combinations. This performance is due to the complementarity between onion and carrot. Onion, a member of the Liliaceae family, develops a shallow root system, whereas carrot, a root vegetable, produces a deeper, vertically oriented taproot. As a result, each crop explores different soil layers for water and nutrients.68 Moreover, carrot roots are known to release exudates that promote microbial growth, contributing to the observed increase in microbial biomass.1,69 These observations are consistent with earlier findings showing that intercropping enhances microbial activity through increased root exudation, improved moisture retention, and greater root surface area.5,15,70,71 The onion-pepper system also resulted in a measurable increase in MBC and microbial load compared to the onion sole crop, though the effect was notably lower than that of onion-carrot. This intermediate performance may be due to weaker root complementarity or less stimulatory exudate profiles in pepper, which may be less efficient at supporting microbial activity in the shared rhizosphere.72,73 In contrast, the onion-fennel intercropping system showed the lowest values of MBC and microbial density. Several factors may explain this underperformance. According to Luqman et al.,74 there is more interspecific competition for soil nutrients, space, water, and light under intercropping conditions than under monocropping. Competition between onion and fennel may result in poor resource sharing due to differing nutrient requirements and the dominance of fennel.1,75-79 Furthermore, fennel is known to release allelopathic compounds that inhibit both onion development and microbial growth.73,78,80 This crop combination may lack any synergistic root exudate interactions, leading to a neutral or even suppressive rhizosphere environment. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that fennel intercropped with onion, garlic, or carrot negatively affects neighboring crop growth,1,73,77 and with work showing fennel dominance in combinations with fenugreek,81 cabbage, and cauliflower.79 The limited effectiveness of this combination may therefore be attributed to both physiological competition and unfavorable biochemical interactions, which reduce microbial activity and soil health. While intercropping generally improved microbial attributes, yield results were more nuanced. Onion monoculture recorded the highest yield. This finding is consistent with studies noting that onions grown alone outperform those intercropped with coriander or fennel,75 or chilies.74 This may be due to reduced interspecific competition and more efficient resource use by onions in monoculture. Fennel, in particular, was highly competitive, with a consistent yield-suppressing effect on onion across seasons.73,77 However, the onion-carrot combination maintained relatively high yields while significantly enhancing microbial activity, suggesting it may offer a beneficial compromise between productivity and soil health. This is supported by the positive correlation (Figure 7) between onion yield and rhizospheric bacterial and actinomycete counts, suggesting that the soil microbiome may play an active role in enhancing crop productivity.57,62 In contrast, the weak correlation between yield and both fungal abundance and microbial biomass carbon suggests these factors may not have had a strong or consistent influence on crop productivity in this study. Although fungi contribute to nutrient mobilization and help stabilize soil structure, their effects may depend on specific environmental conditions or particular mycorrhizal relationships not captured by total fungal counts.82,83 Similarly, microbial biomass carbon, while often used as a broad indicator of microbial activity, may not reflect the presence or activity of key functional microbial groups directly linked to yield.62

Effect of organic fertilization on microbial biomass carbon, microbial load, and yield

Fertilization plays a vital role in enhancing plant development and in promoting soil microbial communities, which are essential for maintaining soil health and productivity. In the present study, both types of fertilizers (organic and mineral) significantly improved onion yield and microbial characteristics compared to the control treatment, demonstrating the strong influence of inputs on the biological functioning of soil. Onion yield was significantly improved with both NPK and compost by approximately 62% compared to the unfertilized control. Onions are particularly sensitive to nutrient deficiencies due to their shallow root systems and limited root branching, making them highly dependent on external fertilizer inputs.84,85 The increase in bacterial count, which rose by 35% and 42% under mineral (NPK) and organic (compost) treatments respectively, suggests that when compost is applied, nutrients are released slowly, minimizing nutrient losses and improving nutrient absorption capacity due to increased cation exchange capacity.86 Both fertilizers also led to similar increases in fungal counts (about 32%) relative to the unfertilized onion treatment, confirming that microbial groups interact positively with improved nutrient availability regardless of fertilizer type. Conversely, Bebber and Richards40 reported that organic fertilization significantly improves functional and prokaryotic taxonomic diversity but does not necessarily impact fungal diversity. Actinomycete measurements demonstrated a strong response to compost, increasing by 40% compared to the control. According to Li et al.,62 actinomycetes are recognized for their ability to decompose complex organic matter and produce antimicrobial compounds that may suppress pathogens, thereby indirectly improving soil functioning and sustainability. Fertilization positively influenced microbial biomass carbon (MBC), although the overall effect was not statistically significant. The highest MBC values were observed in fertilized treatments: CS12 (900 mg/kg), CS11 (780 mg/kg), and CS10 (780 mg/kg). According to Yasin et al.87 and Mirzaei et al.,25 the absence of fertilization can negatively affect microbial biomass due to nutrient depletion. This suggests that compost enhances microbial biomass by improving carbon availability and stimulating microbial activity. These results are in line with previous findings30,88 showing that organic amendments improve soil structure, promote aggregation, and create favorable habitats for microbial communities. Compost offers a diverse and accessible carbon source for microbes,29,42 which promotes microbial growth and may initiate a positive feedback loop supporting long-term carbon storage. As reported by Peng et al.23 and Zhang et al.,24 organic manures increase soil organic matter and microbial activity, thereby enhancing nutrient cycling. The promising results seen here, particularly in compost treatments, confirm the findings of Gupta et al.,63 who observed increased MBC and yield in onion systems following organic amendments. This aligns with the PCA results (Figure 8), where fertilized plots clustered in the quadrant associated with higher microbial activity and yield, reinforcing the importance of soil amendments in enhancing soil biological function and crop performance. Integrating intercropping with organic fertilization presents a promising strategy for improving soil microbial health, nutrient cycling, and long-term agricultural productivity. Numerous studies21,22,57,89,90 have shown that these practices support the accumulation of microbial biomass carbon (MBC), thereby enhancing soil carbon sequestration and contributing to climate change mitigation by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.65 The use of organic amendments instead of synthetic fertilizers has been shown to increase bacterial, fungal, and total microbial biomass by supplying a steady stream of organic substrates that sustain microbial growth.91-94 Organic fertilization is also associated with improved microbial diversity and abundance, as highlighted by Bebber and Richards40 and Lori et al.,95 although effects on fungal diversity may be more variable. In our study, both intercropping and compost application significantly boosted soil microbial populations. This observation is consistent with Rekha et al.,96 who demonstrated that microbial dynamics are strongly influenced by the interaction between cropping systems and fertilization regimes. Moreover, Heo et al.97 reported that organic amendments in intercropping systems can reduce the presence of pathogenic fungi such as Aspergillus and Ilyonectria, indicating that these inputs promote beneficial microbial groups while suppressing harmful ones. Organic manures like compost and biochar have been recognized for their ability to improve soil health and reduce pathogen load.40,44,97 When intercropping is combined with tailored fertilization management, microbial communities tend to exhibit stronger interactions and reduced energetic stress, resulting in more resilient and functionally efficient ecosystems.5 For example, Wang et al.98 showed that combining green manure with intercropping (soybean and milk vetch in tea systems) improved soil multifunctionality under stress conditions, while Dodiya et al.99 reported more efficient nutrient use in intercropping systems due to complementary root architecture and improved humus content. Agricultural management practices and cropping strategies have long been recognized for their critical influence on productivity, soil health, and microbial dynamics.5,64,65,68 These effects are largely attributed to the enrichment of functional genes related to carbon cycling and the long-term stability of soil organic matter. Rai et al.100 further confirmed that integrated nutrient management in legume-based systems improved soil carbon sequestration and reduced the carbon footprint. Similarly, He et al.90 found that combining organic fertilization with potato-onion intercropping enhanced nutrient uptake, regulated microbial communities, and improved overall crop productivity. Compost, when paired with legume-based intercropping, has also been shown to boost olive tree growth and soil health.101 However, it is worth noting that while Jannoura et al.102 observed increased microbial activity with organic fertilization, they did not find a significant effect from intercropping alone. In this study, the proportions of bacterial, fungal, and actinomycete populations increased under different intercropping systems. Both monoculture and intercropping affect microbial communities, but intercropping shows greater sensitivity to microbial community changes than monoculture.57,89 This suggests that intercropping could enhance bacterial and fungal communities within the soil microbiota.57,62

This study highlights the potential of onion-based intercropping systems, particularly when combined with organic fertilization, to enhance both soil microbiological quality and crop productivity in agroecosystems. The onion-carrot combination under compost application (OnCO) emerged as the most effective treatment, showing significant increases in microbial biomass carbon (MBC), fungi, actinomycetes, and bacteria counts, along with the highest yield per plant. Notably, microbial biomass carbon reached up to 946 mg/kg in OnCO during the second growing season, while actinomycetes counts exceeded 7 × 105 UFC/g. These results underline a strong positive correlation between microbial activity and onion yield. These findings demonstrate that sustainable practices such as intercropping and organic inputs can improve the biological health of soils which is an essential factor for long-term agricultural resilience. The use of compost not only enriched microbial diversity but also supported soil microbiome ecological balance. Adopting diversified cropping systems and favoring organic fertilization offers a promising strategy to promote soil biodiversity, improve yield, and reduce dependency on synthetic inputs. These findings offer practical recommendations for developing biologically enriched, productive onion cultivation systems and emphasize the critical role of soil microbiomes in advancing sustainable vegetable production. However, while this study provided important quantitative insights into microbial abundance and activity, a deeper understanding of soil microbial diversity in Moroccan agroecosystems would benefit from qualitative approaches. Techniques such as metagenomic analysis could further reveal the taxonomic composition and functional potential of microbial communities, offering a more comprehensive view of soil ecosystem health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

NEG conceptualized the study. YE designed the study. IL and AI applied the methodology. YE performed the experiments and analysed the data. KD and FR supervised the study, funding acquisition, performed validation and project administration. MF performed the statistical analyses and contributed to data curation. NEG performed validation. YE wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analysed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Elouattassi Y, Ferioun M, El Ghachtouli N, Derraz K, Rachidi F. Enhancing onion growth and yield through agroecological practices: Organic fertilization and intercropping. Acta Ecologica Sinica. 2023;44(3):547-557.

Crossref - Petrovic B, Kopta T, Pokluda R. Effect of biofertilizers on yield and morphological parameters of onion cultivars. Folia Horticulturae. 2019;31(1):51-59.

Crossref - de Haan JL, Vasseur L. Above and below ground interactions in monoculture and intercropping of onion and lettuce in greenhouse conditions. Am J Plant Sci. 2014;5(21):3319.

Crossref - Ndjadi SS, Vissoh P V, Vumilia RK, et al. Yield potential and land-use efficiency of onion (Allium cepa L.) intercropped with peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) under organic soil fertility management in South-Kivu, Eastern DR Congo. Bulg J Agric Sci. 2022;28(4):647-657.

- Elouattassi Y, Ferioun M, El Ghachtouli N, Derraz K, Rachidi F. Agroecological concepts and alternatives to the problems of contemporary agriculture: Monoculture and chemical fertilization in the context of climate change. J Agric Environ Int Dev. 2023;117(2):41-98.

Crossref - Sharma SD, Kumar P, Bhardwaj SK, Chandel A. Agronomic performance, nutrient cycling and microbial biomass in soil as affected by pomegranate based multiple crop sequencing. Sci Hortic. 2015;197:504-515.

Crossref - Lopez-Garcia D, Carrascosa-Garcia M. Sustainable food policies without sustainable farming? Challenges for agroecology-oriented farmers in relation to urban (sustainable) food policies. J Rural Stud. 2024;105:103160.

Crossref - Requier-Desjardins M, Boughamoura O, Lemaitre-Curri E. Characterizing Agroecology in North Africa, a Review of 88 Sustainable Agriculture Projects. Land (Basel). 2024;13(9):1457.

Crossref - Altieri MA, Nicholls CI. Agroecology Scaling Up for Food Sovereignty and Resiliency. In: Lichtfouse, E. (eds) Sustainable Agriculture Reviews. Sustainable Agriculture Reviews, vol 11. Springer, Dordrecht.. 2012:1-29.

Crossref - Bybee-Finley KA, Ryan MR. Advancing intercropping research and practices in industrialized agricultural landscapes. Agriculture (Switzerland). 2018;8(6):1-24.

Crossref - Shah M, Gul S, Baloch MK, et al. Soil properties under monocropping and tree-based intercropping systems. Materion. 2025;2(1):1-6.

Crossref - Gardarin A, Celette F, Naudin C, et al. Intercropping with service crops provides multiple services in temperate arable systems: a review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2023;42:39.

Crossref - Maitra S. Potential of Intercropping System in Sustaining Crop Productivity. Int J Agric Environ Biotechnol. 2019;12(1).

Crossref - Altieri MA. Agroecology: The Science of Sustainable Agriculture. Intermediate Technology Publications Ltd (ITP). 1995:433. https://repository.graduateinstitute.ch/record/82348/. Accessed April 19, 2023.

- Altieri MA. Agroecology: The Science of Sustainable Agriculture. CRC Press. 2018.

Crossref - Bitew Y, Alemayehu G, Adego E, Assefa A. Boosting land use efficiency, profitability and productivity of finger millet by intercropping with grain legumes. Cogent Food Agric. 2019;5(1):1702826.

Crossref - Xu Z, Li C, Zhang C, Yu Y, van der Werf W, Zhang F. Intercropping maize and soybean increases efficiency of land and fertilizer nitrogen use; A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2020;246:107661.

Crossref - Kaur G, Gupta G, Hooda K. Intercropping Systems in Wheat (Triticum sativum L.) for Insect Pests and Disease Management – A Review. J Pharm Res Int. 2021;33(53B):122-129.

Crossref - Jaya IKD, Santoso BB, Jayaputra. Intercropping red chili with leguminous crops to improve crop diversity and farmers’ resilience to climate change effects in dryland. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2023;1192(1):012001.

Crossref - Solanki MK, Wang FY, Li CN, et al. Impact of Sugarcane-Legume Intercropping on Diazotrophic Microbiome. Sugar Tech. 2020;22(1):52-64.

Crossref - Sun Y, Chen L, Zhang S, et al. Plant interaction patterns shape the soil microbial community and nutrient cycling in different intercropping scenarios of aromatic plant species. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:888789.

Crossref - Cuartero J, Pascual JA, Vivo JM, et al. A first-year melon/cowpea intercropping system improves soil nutrients and changes the soil microbial community. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2022;328:107856.

Crossref - Peng L, Deng S, Wu Y, et al. A rapid increase of soil organic carbon in paddy fields after applying organic fertilizer with reduced inorganic fertilizer and water-saving irrigation is linked with alterations in the structure and function of soil bacteria. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2025;379:109353.

Crossref - Zhang S, Huang F, Guo S, et al. Mitigation of soil organic carbon mineralization in tea plantations through replacement of pruning litter additions with pruning litter derived biochar and organic fertilizer. Ind Crops Prod. 2025;225:120518.

Crossref - Mirzaei M, Holl D, Hassine MB, et al. Soil Health and Nitrogen Dynamics as Affected by Organic Amendments in Monocropping and Intercropping of Maize and Mung Bean Systems. Soil Use Manag. 2025;41(3):e70122.

Crossref - Hao X, Abou Najm M, Steenwerth KL, Nocco MA, Basset C, Daccache A. Are there universal soil responses to cover cropping? A systematic review. Sci Total Environ. 2023;861:160600.

Crossref - Wang B, An S, Liang C, Liu Y, Kuzyakov Y. Microbial necromass as the source of soil organic carbon in global ecosystems. Soil Biol Biochem. 2021;162:108422.

Crossref - Jindo K, Chocano C, Melgares de Aguilar JM, Gonzalez D, Hernandez T, Garcia C. Impact of Compost Application during 5 Years on Crop Production, Soil Microbial Activity, Carbon Fraction, and Humification Process. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2016;47(16):1907-1919.

Crossref - Kutos S, Stricker E, Cooper A, et al. Compost amendment to enhance carbon sequestration in rangelands. J Soil Water Conserv. 2023;78(2):163-177.

Crossref - Wang D, Lin JY, Sayre JM, et al. Compost amendment maintains soil structure and carbon storage by increasing available carbon and microbial biomass in agricultural soil-A six-year field study. Geoderma. 2022;427:116117.

Crossref - Nazir R, Rehman S, Nisa M, ali Baba U. Exploring bacterial diversity: from cell to sequence. In: Bandh SA, Shafi S, Shameem N (eds) Freshwater Microbiology Perspectives of Bacterial Dynamics in Lake Ecosystems. Academic Press; 2019:263-306.

Crossref - Omer M, Idowu OJ, Pietrasiak N, et al. Agricultural practices influence biological soil quality indicators in an irrigated semiarid agro-ecosystem. Pedobiologia (Jena). 2023;96:150862.

Crossref - Habekost M, Eisenhauer N, Scheu S, Steinbeiss S, Weigelt A, Gleixner G. Seasonal changes in the soil microbial community in a grassland plant diversity gradient four years after establishment. Soil Biol Biochem. 2008;40(10):2588-2595.

Crossref - Piazza G, Ercoli L, Nuti M, Pellegrino E. Interaction between conservation tillage and nitrogen fertilization shapes prokaryotic and fungal diversity at different soil depths: evidence from a 23-year field experiment in the Mediterranean area. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2047.

Crossref - Mangla H, Dave S, Jain S, Pathak H. Study of Multiple Regression Modal between Soil Properties and Colony-forming Unit Collected from Diverse Regions of Rajasthan, India. Int J Environ Health Eng. 2025;14(3):18.

Crossref - Nyawade SO, Karanja NN, Gachene CKK, Gitari HI, Schulte-Geldermann E, Parker ML. Short-term dynamics of soil organic matter fractions and microbial activity in smallholder potato-legume intercropping systems. Appl Soil Ecol. 2019;142:123-135.

Crossref - Tang X, Zhang Y, Jiang J, et al. Sugarcane/peanut intercropping system improves physicochemical properties by changing N and P cycling and organic matter turnover in root zone soil. Peer J. 2021;9:e10880.

Crossref - Zhou L, Wang Y, Xie Z, et al. Effects of lily/maize intercropping on rhizosphere microbial community and yield of Lilium davidii var. unicolor. J Basic Microbiol. 2018;58(10):892-901.

Crossref - Dang K, Gong X, Zhao G, Wang H, Ivanistau A, Feng B. Intercropping alters the soil microbial diversity and community to facilitate nitrogen assimilation: a potential mechanism for increasing proso millet grain yield. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:601054.

Crossref - Bebber DP, Richards VR. A meta-analysis of the effect of organic and mineral fertilizers on soil microbial diversity. Appl Soil Ecol. 2022;175:104450.

Crossref - Janke RR, Menezes-Blackburn D, Al Hamdi A, Rehman A. Organic Management and Intercropping of Fruit Perennials Increase Soil Microbial Diversity and Activity in Arid Zone Orchard Cropping Systems. Sustainability. 2024;16(21):9391.

Crossref - Sharaf H, Thompson AA, Williams MA, Peck GM. Compost applications increase bacterial community diversity in the apple rhizosphere. Soil Science Society of America Journal. 2021;85(4):1105-1121.

Crossref - Li S, Wu F. Diversity and co-occurrence patterns of soil bacterial and fungal communities in seven intercropping systems. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1521.

Crossref - Asiloglu R, Samuel SO, Sevilir B, et al. Biochar affects taxonomic and functional community composition of protists. Biol Fertil Soils. 2021;57:15-29.

Crossref - Yang Y, Zhang S, Li N, et al. Metagenomic insights into effects of wheat straw compost fertiliser application on microbial community composition and function in tobacco rhizosphere soil. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6168.

Crossref - Tang X, Jiang J, Huang Z, et al. Sugarcane/peanut intercropping system improves the soil quality and increases the abundance of beneficial microbes. J Basic Microbiol. 2021;61(2):165-176.

Crossref - Moghbeli T, Bolandnazar S, Panahande J, Raei Y. Evaluation of yield and its components on onion and fenugreek intercropping ratios in different planting densities. J Clean Prod. 2019;213:634-641.

Crossref - Vance ED, Brookes PC, Jenkinson DS. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol Biochem. 1987;19(6):703-707.

Crossref - Vieira FCS, Nahas E. Comparison of microbial numbers in soils by using various culture media and temperatures. Microbiol Res. 2005;160(2):197-202.

Crossref - Chave M, Dabert P, Brun R, Godon JJ, Poncet C. Dynamics of rhizoplane bacterial communities subjected to physicochemical treatments in hydroponic crops. Crop Protection. 2008;27(3-5):418-426.

Crossref - Dhingra OD, Sinclair JB (Eds.) Basic Plant Pathology Methods. CRC press. 2017.

Crossref - Qin S, Miao Q, Feng WW, et al. Biodiversity and plant growth promoting traits of culturable endophytic actinobacteria associated with Jatropha curcas L. growing in Panxi dry-hot valley soil. Appl Soil Ecol. 2015;93:47-55.

Crossref - Ferioun M, Zouitane I, Bouhraoua S, et al. PGPR consortia promote soil quality and functioning in barley rhizosphere under different levels of drought stress. Ecological Frontiers. 2025;45(2):444-454.

Crossref - Ferioun M, Bouhraoua S, Srhiouar N, et al. Advanced multivariate approaches for selecting Moroccan drought-tolerant barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars. Ecological Frontiers. 2024;44(4):820-828.

Crossref - Ferioun M, Bouhraoua S, Boussakouran A, et al. Enhancing drought tolerance and yield production in barley cultivars using PGPR consortia. S Afr J Bot. 2025;182:56-67.

Crossref - Behera N, Sahani U. Soil microbial biomass and activity in response to Eucalyptus plantation and natural regeneration on tropical soil. For Ecol Manage. 2003;174(1-3):1-11.

Crossref - Liu PF, Zhao YK, Ma JN, et al. Impact of various intercropping modes on soil quality, microbial communities, yield and quality of Platycodon grandiflorum (Jacq.) A. DC. BMC Plant Biol. 2025;25(1):503.

Crossref - Du L, Huang B, Du N, Guo S, Shu S, Sun J. Effects of garlic/cucumber relay intercropping on soil enzyme activities and the microbial environment in continuous cropping. HortScience. 2017;52(1):78-84.

Crossref - Liu Y, Fan Y, Kuzyakov Y, Dai J, Zhang C, Li C. Effects of maize/soybean intercropping on nitrogen mineralization and fungal communities in soil. Plant Soil. 2025:1-15.

Crossref - Yin R, Zhang H, Huang J, Lin X, Wang J, Cao Z. Comparison of microbiological properties between soils of rice-wheat rotation and vegetable cultivation. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Fertilizers. 2004;10(1):57-62.

- Li SM, Li L, Zhang FS, Tang C. Acid phosphatase role in chickpea/maize intercropping. Ann Bot. 2004;94(2):297-303.

Crossref - LI Y, LI K, LI J, et al. Effects of organic fertilizer and intercropping on soil microbial characteristics and yield and quality of red pitaya in dry-hot region. Chinese Journal of Ecology. 2024;43(3):656-664.

Crossref - Gupta R, Rai AP, Swami S. Soil enzymes, microbial biomass carbon and microbial population as influenced by integrated nutrient management under onion cultivation in sub-tropical zone of Jammu. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2019;8(3):194-199.

- Li N, Gao D, Zhou X, Chen S, Li C, Wu F. Intercropping with potato-onion enhanced the soil microbial diversity of tomato. Microorganisms. 2020;8(6):834.

Crossref - Morugan-Coronado A, Perez-Rodriguez P, Insolia E, Soto-Gomez D, Fernandez-Calvino D, Zornoza R. The impact of crop diversification, tillage and fertilization type on soil total microbial, fungal and bacterial abundance: A worldwide meta-analysis of agricultural sites. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2022;329:107867.

Crossref - Xu Y, Tang H, Xiao X, et al. Effects of long-term fertilization management practices on soil microbial carbon and microbial biomass in paddy soil at various stages of rice growth. Rev Bras Cienc Solo. 2018;42:111.

Crossref - Zhou X, Yu G, Wu F. Effects of intercropping cucumber with onion or garlic on soil enzyme activities, microbial communities and cucumber yield. Eur J Soil Biol. 2011;47(5):279-287.

Crossref - Seremesic S, Manojlovic M, Ilin Z et al. Effect of intercropping on the morphological and nutritional properties of carrots and onions in organic agriculture. Journal on Processing and Energy in Agriculture. 2018;22(2):80-84.

Crossref - Singh G, Mukerji KG. Root Exudates as Determinant of Rhizospheric Microbial Biodiversity. In: Mukerji KG, Manoharachary C, Singh J (eds) Microbial Activity in the Rhizoshere. Soil Biology, vol 7. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 2006:39-53.

Crossref - Duchene O, Vian JF, Celette F. Intercropping with legume for agroecological cropping systems: Complementarity and facilitation processes and the importance of soil microorganisms. A review. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2017;240:148-161.

Crossref - Rhioui W, Al Figuigui J, Mikou K, Benabderrahmane A, Belmalha S. Effect of mulching, aqueous extract of Thymus zygis (L.) and Melia azedarach (L.), and intercropping with Coriandrum sativum (L.), on weed management, yield, agronomic and physiological parameters of bell pepper crop (Capsicum annuum L.). Vegetos. 2024 (37):701-716.

Crossref - Kabura BH, Musa B, Odo PE. Evaluation of the yield components and yield of onion (Allium cepa L.)-pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) intercrop in the Sudan Savanna. Journal of Agronomy. 2008;7(1):88-92.

Crossref - Zyada HG, Mohsen AAM, Nosir WS. Using intercropping systems to obtain high yield and good competitive indices of fennel and onion under different potassium fertilizer levels. Zagazig Journal of Agricultural Research. 2022;49(2):193-207.

Crossref - Luqman, Hussain Z, Ilyas M, Khan IA, Bakht T. Influence of sowing orientation and intercropping of chilies on onion yield and its associated weeds in peshawar, Pakistan. Pak J Bot. 2020;52(1):95-100.

Crossref - Abdelkader MA, Mohsen AAM. Effect of intercropping patterns on growth, yield components, chemical constituents and comptation indices of onion, fennel and coriander plants. Zagazig Journal of Agricultural Research. 2016;43(1):67-83.

Crossref - Willey RW, Rao MR. A competitive ratio for quantifying competition between intercrops. Exp Agric. 1980;16(2):117-125.

Crossref - Mehta RS, Singh B, Meena SS, Lal G, Singh R, Aishwath OP. Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.) based intercropping for higher system productivity. International J Seed Spices. 2015;5(1):56-62.

- Ghaderimokri L, Rezaei-Chiyaneh E, Ghiyasi M, Gheshlaghi M, Battaglia ML, Siddique KHM. Application of humic acid and biofertilizers changes oil and phenolic compounds of fennel and fenugreek in intercropping systems. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):5946.

Crossref - Yadav BL, Patel AM, Patel BS, Shaukat A, Jitendra S. Quality and soil fertility as influenced by different row spacing and intercropping systems in Rabi fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.). Advance Research Journal of Crop Improvement. 2017;8(1):75-79.

Crossref - Rezaei-Chiyaneh E, Amirnia R, Machiani MA, Javanmard A, Maggi F, Morshedloo MR. Intercropping fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) with common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) as affected by PGPR inoculation: A strategy for improving yield, essential oil and fatty acid composition. Sci Hortic. 2020;261:108951.

Crossref - Boori PK, Shivran AC, Meena S, Giana GK. Growth and productivity of fennel (Foeniculum Vulgare Mill.) as influenced by intercropping with fenugreek (Trigonella Foenum-Graecum L.) and sulphur fertilization. Agricultural Science Digest-A Research Journal. 2017;37(1):32-36.

Crossref - Pavithra D, Yapa N. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation enhances drought stress tolerance of plants. Groundw Sustain Dev. 2018;7:490-494.

Crossref - Turan V. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and pistachio husk biochar combination reduces Ni distribution in mungbean plant and improves plant antioxidants and soil enzymes. Physiol Plant. 2021;173(1):418-429.

Crossref - Amare G. Review on Mineral Nutrition of Onion (Allium cepa L). Open Biotechnol J. 2020;14:134-144.

Crossref - Brewster JL. Onions and other vegetable Alliums Wallingford. CAB International Wallingford. 1994:236.

- Brady NC. The Nature and Properties of Soils, Macmillan Publishing Company. New York. 1990.

- Yasin HM, Nabiyu A, Abebe T. Analyses of agronomic and system productivity of maize (Zea mays L.)-common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Intercropping under organic and inorganic fertilization in southwestern Ethiopia. European Journal of Agronomy. 2025;171:127791.

Crossref - Liang C, Schimel JP, Jastrow JD. The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2(8):1-6.

Crossref - Wang J, Lu X, Zhang J, et al. Intercropping perennial aquatic plants with rice improved paddy field soil microbial biomass, biomass carbon and biomass nitrogen to facilitate soil sustainability. Soil Tillage Res. 2021;208:104908.

Crossref - He X, Xie H, Gao D, Rahman MKU, Zhou X, Wu F. Biochar and Intercropping With Potato-Onion Enhanced the Growth and Yield Advantages of Tomato by Regulating the Soil Properties, Nutrient Uptake, and Soil Microbial Community. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:695447.

Crossref - Song D, Dai X, Guo T, et al. Organic amendment regulates soil microbial biomass and activity in wheat-maize and wheat-soybean rotation systems. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2022;333:107974.

Crossref - Ning C, Gao P, Wang B, Lin W, Jiang N, Cai K. Impacts of chemical fertilizer reduction and organic amendments supplementation on soil nutrient, enzyme activity and heavy metal content. J Integr Agric. 2017;16(8):1819-1831.

Crossref - Misra P, Maji D, Awasthi A, et al. Vulnerability of Soil Microbiome to Monocropping of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants and Its Restoration Through Intercropping and Organic Amendments. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2604.

Crossref - Ferioun M, Zouitane I, Bouhraoua S, et al. Applying microbial biostimulants and drought-tolerant genotypes to enhance barley growth and yield under drought stress. Front Plant Sci. 2025;15:1494987.

Crossref - Lori M, Symnaczik S, Mader P, De Deyn G, Gattinger A. Organic farming enhances soil microbial abundance and activity-A meta-analysis and meta-regression. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180442.

Crossref - Rekha RG, Desai BK, Umesh MR, Rao S, Shubha S. Soil microflora as influenced by different intercropping systems and nitrogen management practices. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2017;6(6):889-891.

- Heo YM, Lee H, Kim K, et al. Fungal diversity in intertidal mudflats and abandoned solar salterns as a source for biological resources. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(11):601.

Crossref - Wang T, Duan Y, Liu G, et al. Tea plantation intercropping green manure enhances soil functional microbial abundance and multifunctionality resistance to drying-rewetting cycles. Sci Total Environ. 2022;810:151282.

Crossref - Dodiya TP, Gadhiya AD, Patel GD. A Review: Effect of Inter Cropping in Horticultural Crops. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2018;7(2):1512-1520.

Crossref - Rai AK, Basak N, Dixit AK, et al. Changes in soil microbial biomass and organic C pools improve the sustainability of perennial grass and legume system under organic nutrient management. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1173986.

Crossref - Chehab H, Tekaya M, Ouhibi M, et al. Effects of compost, olive mill wastewater and legume cover cropson soil characteristics, tree performance and oil quality of olive trees cv. Chemlali grown under organic farming system. Sci Hortic. 2019;253:163-171.

Crossref - Jannoura R, Joergensen RG, Bruns C. Organic fertilizer effects on growth, crop yield, and soil microbial biomass indices in sole and intercropped peas and oats under organic farming conditions. European Journal of Agronomy. 2014;52(Part B):259-270.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2026. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.