ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Spodoptera frugiperda is one of the most destructive pests affecting economically important crops like maize and sorghum. Traditional management strategies rely highly on chemical insecticides, leading to environmental concerns and resistance development issues, necessitating alternative strategies for effective pest management. Biopesticides, particularly Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt)-based formulations, offer an environment friendly alternative due to their specificity and safety. However, the efficacy of the Bt often hindered by issues related to stability and application efficiency. This research focuses on development of formulation and evaluation of Bt-based water-soluble emulsion for the management of S. frugiperda. The Bt strain T414 containing cry and vip genes, was used to formulate a stable water-soluble emulsion. Mineral oil (light liquid paraffin) was chosen as a carrier oil, and Tween®80 and Span®80 were used as surfactant mixtures for enhanced miscibility, and stability. The final formulation, incorporating glycerol and trehalose as stabilizers, exhibited a droplet size of 177-187 nm and zeta potential of -28 mV, indicating good colloidal stability. The pH remained within an optimal range (6.92), and viscosity analysis confirmed shear-thinning behaviour, ensuring ease of application. Laboratory bioassay demonstrated that the emulsion formulation exhibited higher insecticidal activity, with a calculated LC50 of 0.006 µg/ml, compared to the spore-crystal mixture. This enhanced insecticidal efficacy suggests improved bioavailability of the active ingredients in the emulsion formulation. This study emphasizes the ability of Bt-based water-soluble emulsion formulation as environmentally safe and effective alternative for pest management, reducing dependence on chemical insecticides, subsequently promoting sustainable pest control.

Bacillus thuringiensis, Spodoptera frugiperda, Emulsion Formulation, Bioassay, Pest Management

Insect pests are the most important challenges faced by global agriculture, posing a major threat to crop productivity and food security.1 Insect pests, particularly in the order Lepidoptera, account for extensive damage to a wide range of crops due to their voracious feeding habit and rapid reproduction and are difficult to manage.2 Among the lepidopteran insect pests, Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith, 1797), commonly known as the fall armyworm, is known to infest more than 100 plant species, with a preference for grasses like maize and sorghum.3 S. frugiperda, originally from the Neotropical region of Central and South America, has recently become one of the most significant global pests infesting maize.4 In 2016, fall armyworm (FAW) was recorded in West Africa, marking its first incidence outside its native range of the Americas.5 It quickly invaded neighbouring countries, before reaching Middle East and India in 2018. Since then, it has continued to expand throughout Asia and, by early 2020, has reached mainland Australia.6 Its ability to complete multiple overlapping generations annually, combined with its high fecundity and migratory potential, makes it a persistent and challenging pest to control.7 Infestations by S. frugiperda lead to maize yield losses ranging from 11.57% to 58%, with noticeable damage on leaves, silk, tassels, and cob, causing substantial reductions in final yield.8

Traditionally farmers have relied heavily on chemical insecticides to manage S. frugiperda infestations.9 Over time, the discriminate and excessive use of these chemicals have also led to environmental contamination, adverse effects on non-target organisms, and the accumulation of toxic residues in soil, water, and food.10 There are numerous reports on the development of insecticides resistant populations in FAW.11 Biopesticides derived from natural sources such as bacteria, fungi, viruses and nematodes, offer environmentally safe and targeted solutions for pest control.12 Among biopesticides, entomopathogenic bacteria, particularly Bacillus thuringiensis is one of the most widely used microbial biopesticides globally.13 Bt produces crystal protein, also known as δ-endotoxin, which is toxic to various insect pests, primarily to members of the orders Lepidoptera, Diptera, and Coleoptera.14 When ingested by susceptible insects, the Cry proteins disrupt the midgut cells, leading to lysis and ultimately insect mortality.15 Bt-based biopesticides, such as Dipel and Biobit, are commercially available and have been successfully used to manage lepidopteran pests, including S. frugiperda.16 The shelf-life and stability of bio-based products present challenges that could hinder their widespread adoption, with particular emphasis on the formulation of the inoculant, further emphasizing the need for innovative approaches to enhance the efficacy and susceptibility of Bt-based pest control strategies.

This study focuses on the formulation and assessment of Bt-based water-soluble emulsion against S. frugiperda under laboratory condition. The use of water-soluble emulsion offers several benefits including ease of application, improved adherent to plant surfaces, and better penetration into pest feeding sites. By integrating the benefits of biopesticide with advancement in formulation technology, this research aims to contribute to sustainable pest management practices.

Bacillus thuringiensis strain and culture

B. thuringiensis strain T414, used in this study, was obtained from the repository of Department of Plant Biotechnology, Centre for Plant Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore, India. Strain T414 was selected for biopesticide production and formulation studies due to its reported toxicity, against a broad spectrum of lepidopteran insect larvae which could be attributed to the presence of genes cry1Aa, cry1Ab, cry1Ac, cry2Aa, cry2Ab, cyt1, and vip3Aa.17

The Bt culture was revived from glycerol stock on T3 agar medium (per litre: 2.0 g Tryptose, 3.0 g Tryptone, 1.5 g Yeast extract powder, 8.9 g Na2HPO4, 6.9 g NaH2PO4, and 0.005 g MnCl and 10.0 g agar, adjusted to pH 6.8-7.0) incubated at 30 °C for 24 hours to allow the revival of bacterial colonies. A loopful of the revived bacterial culture was inoculated into T3 broth (100 ml) in 500 ml conical flask. The inoculated culture was incubated at 30 °C for 48 hours in shaker-incubator set at 200 rpm. Once the culture achieved approximately 90% cell lysis, the sporulated culture was centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5810)18 and resulting pellet was washed twice with 10 mM PBS and diluted with 2 ml of PBS buffer for further use.19

Selection of oil and hydrophilic surfactant for emulsion

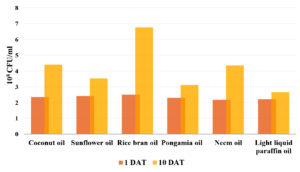

Various oils, including edible oils (coconut oil, rice bran oil, sunflower oil), non-edible oils (pongamia oil and neem oil) and mineral oil (light liquid paraffin) were placed in a cavity block (40 x 40 mm) and inoculated with 10% of Bt culture broth. Observations were made macroscopically for turbidity and CFU (Colony-forming unit) count on 10th day.

Non-ionic hydrophilic surfactants, including Tween 80, Tween 20, Triton X-100, were individually mixed with the above selected oil, at a ratio of 2:5 (v/v) of 0.7 ml per batch. These components were mixed together using a magnetic stirrer at 1000 rpm and added with 9.3 ml of PBS buffer. Visual assessments were performed to monitor the phase separation.20 The most suitable non-ionic hydrophilic surfactants were selected based on the miscibility condition and phase separation time.

Selection of surfactant mixture

The chosen non-ionic hydrophilic surfactant was combined with 2% of the lipophilic surfactants, Span®20, Span®80. The blends were prepared in ratios of 4:1, 3:2 (v/v) to achieve a hydrophilic-lipophilic balances (HLBs) of 10.

Preparation of water-soluble emulsion

The optimized surfactant blends were incorporated into a final formulation, comprising of selected oil, glycerol as omniprotectant, trehalose to maintain the viability of cells and Bt spore crystal mixture with PBS buffer. The components were thoroughly mixed by homogenization to ensure uniform distribution and stability of emulsion.21 The prepared formulation was divided and stored at four different temperatures (4 °C, 20 °C, 27 ± 2 °C and 37 ± 2 °C).22

Characterization of the water-soluble emulsion

pH determination

pH of the formulations was measured using a Mettler Toledo FiveEasy™ pH/mV bench meter, after calibrating the pH meter with standard buffer solution at 25 °C.

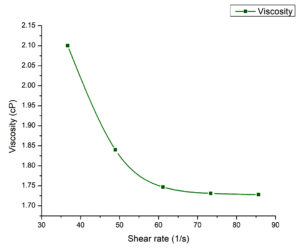

Viscosity determination of emulsion

The viscosity was determined using the Rotational Viscometer Anton Paar’s ViscoQC 300 at 25 °C for the emulsion formulation. Using spindle type UL26 with over 90% torque, the apparatus was auto-zeroed and calibrated before use. The samples were exposed to different shear rate ranging from 1 to 100 s-1 to assess their flow properties.23

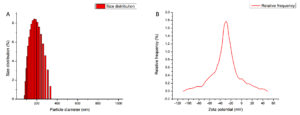

Droplet size and Zeta potential of emulsion

The droplet size of the emulsion formulation was determined as the hydrodynamic diameter or average particle size using Dynamic light scattering (DLS) with Malvern Panalytical Zetasizer Ver. 7.13. Zeta potential analysis was conducted to evaluate the stability of the emulsion using the same instrument.

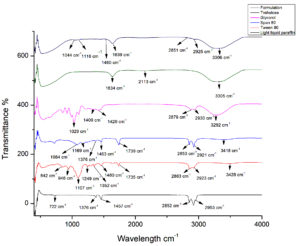

Infrared spectroscopic analysis

The FT-IR (FT/IR-8X1 Type A model, JASCO International) was used for analysing the Infrared spectroscopic patterns of selected oil, surfactants, other additives, and emulsion formulation.

Stability assessment under accelerated conditions

The emulsion formulation was placed in centrifuge vials and subjected to centrifugation using Eppendorf Centrifuge 5810 at 4,000 rpm for 10 min over two consecutive runs. Following centrifugation, the sample was examined macroscopically for phase separation or liquefaction signs. The creaming index was determined by following the method of Petrovic et al.24

Creaming index (%) = HS / HE x 100

Where HE is the total height of the emulsion, and HS is the height of the cream layer as measured after centrifugation. Smaller the value indicates greater stability of the emulsion.

Short term stability evaluation

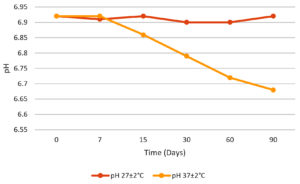

The physical stability of the emulsions stored in vials were assessed under both room temperature conditions (27 ± 2 °C), and at higher temperature (37 ± 2 °C). The samples were monitored for changes in pH, odour and colour, along with any indication of phase separation at specific time intervals of 0, 7, 15, 30, 60, and 90 days.25

Contact angle

A standard contact angle meter (KYOWA – FAMAS; Kyowa Interface Science Co., Japan) was utilized to determine the contact angle. 10 µL droplet of emulsion was precisely dispensed onto the surface of a maize leaf using an automated pipette. The mean contact angle for each trial was calculated based on the tangent angle at emulsion droplet surface. Image analysis was conducted using FAMAS software.

Shelf-life evaluation of the formulation

The shelf-life of the formulations was determined from samples stored at different temperatures (4 °C, 20 °C, 27 ± 2 °C and 37 ± 2 °C). The samples were drawn at monthly intervals for a period of 6 months with three replicates for each condition and assessed for the CFU/ml count of Bt by serial dilution and spread plate method on T3 media. The CFU/ml was calculated using the formula:

CFU/ml = (Number of colonies × Dilution factor) / Volume of culture plated (in ml)

Efficacy of Bt emulsion formulation under laboratory condition

The insecticidal activity of the prepared formulation was evaluated against neonates of S. frugiperda using the leaf dip method. Maize leaf discs of 2.5 cm diameter were used for bioassay. The leaf discs were embedded on the 1% agar surface of 3-4 mm thickness in the plastic cups (3 cm diameter) to avoid desiccation. One larva was released on each leaf disc without any physical damage to the larva. Each treatment consists of three replicates, with 10 larvae per replicate. Observations of larval mortality were recorded at 24 hour intervals for a duration of 7 days. The LC50 value was determined through bioassays at different concentrations viz., 0.0025, 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1 ppm. A commercially available formulation Dipel L Bt kurstaki strain HD-1, 3.5% ES formulation (17600 IU/mg potency) was utilized as a reference standard for comparison.

Statistical analysis

Observations of larval mortality in the laboratory bioassays were used to determine the lethal concentration for 50% mortality (LC50). The data were analysed using probit regression analysis, with POLO-PC software.

Selection of oil and surfactant blend

Among various oils tested, mineral oil (LLP) was selected for emulsion formulation due to its ability to maintain the stability of CFU count on Bt T414 spores over a 10-day period. Unlike other oils, mineral oil demonstrated stability by maintaining a consistent CFU count (Figure 1). Additionally, it exhibited lower turbidity (Supplementary Figure 1), which is indicative of its ability to prevent excessive growth of Bt while keeping the spores viable. This property of mineral oil makes it an ideal choice for long-term stability and efficacy of the emulsion formulation.

In order to develop emulsion formulation, hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) of the surfactant or surfactant mixture is considered as a crucial factor. It is associated with the interaction of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic segments of a surfactant molecule. Typically, oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions require surfactants with HLB values ranging from 8 and 18, whereas, water-in-oil (W/O) emulsions are formed using surfactants with HLB values between 3 and 7.26,27 Among the surfactants tested, Tween®80 exhibited the highest solubilization capacity as a hydrophilic surfactant compared to Tween®20 and Triton® X-100. In our experiments, we obtained complete miscibility without phase separation of water and oil with 2% of Tween®80. For the other surfactants tested, phase separation was obtained (Supplementary Figure 2). Therefore, they were not used in further studies.

It is identified that a single surfactant is often insufficient to develop a stable single-phase emulsion, and an appropriate combination of surfactants may be necessary to optimize emulsion formulation.28 Therefore, Tween®80 was combined with the hydrophobic surfactants, Span®20 and Span®80 to create surfactant mixture, allowing for screening and selection of optimal surfactant mixture for preparing oil-in-water emulsions. The solubilization results of surfactant mixture indicated that the Tween®80 and Span®80 mixture at a 3:2 (v/v) ratio exhibited the highest miscibility capacity, with an HLB value of 10.72.

Incorporation of Bt spore-crystal mixture, other additives and homogenization

The optimized surfactant blend (2%) was incorporated into the final formulation to create a stable and effective oil-in-water emulsion. The formulation (Figure 2) includes 5% mineral oil (Light liquid paraffin) as the oil phase, which served as a carrier to improve the delivery and adhesion of active ingredient along with 73% of PBS buffer with 10% of Bt-spore crystal which provided active ingredient. Additionally, 5% glycerol was added, which functions effectively as a co-surfactant and in dispersed phases due to its salting-in effect, enabling the incorporation of glycerol into the surfactant layer and enhancing interfacial fluidity.29 Furthermore, 5% on 10 mM trehalose was included as a stabilizer to maintain the structural integrity and preserve the virulence of the spores. Trehalose, a disaccharide, is known for its protective properties, particularly its ability to stabilize proteins, spores, and other biological materials during formulation and storage, ensuring the viability of culture over time.30

To ensure thorough mixing and a stable emulsion, all components were combined and mixed using magnetic stirrer set at 1000 rpm for 24 hours. This stirring process was essential to achieve uniform distribution of the oil droplets within the water phase, minimize phase separation and to ensure homogeneity.

Characterization of the water-soluble emulsion

The pH of the emulsion formulation was 6.92, indicating that the emulsion is nearly neutral. The pH level is within the optimal range of Bt growth and viability. El-Bendary et al.,31 have demonstrated that an initial pH between 6.5 and 8.5 influences spore production and bacterial growth, 6.5 yielding the highest growth. Since Bt growth typically occurs within a pH range of 6.5 to 8.5, the initial pH of 6.92 is well suited for maintaining microbial activity and ensuring a stable environment for endotoxin and spore viability. The emulsion pH balance suggests its suitability for long term storage, field application and environmental compatibility.

The flow curve of oil-in water emulsion (Figure 3) decreases in viscosity as shear rate increases, confirming that the emulsion exhibits shear-thinning, which is also known as pseudoplastic behaviour, is common in emulsions and dispersions where structural elements breakdown under shear.32 The viscosity drops, from 2.1 cP at 36.69 s-1 to 1.73 cP at 85.63 s-1 showing a progressive reduction in resistance to flow with increasing shear, making the emulsion well-suited for application requiring controlled flow properties.

DLS analysis revealed that droplets with mean sizes between 177 to 187 nm

(Figure 4A). Based on the size distribution the emulsion can be classified as nanoemulsion (NE) since nanoemulsions typically have droplet size within the 20-200 nm range.33 Nanoemulsions are isotropic, kinetically stable in which two immiscible phases such as oil and water, are combined into single phase mixture with the aid of surfactants.34 The stability of these emulsions is attributed to the small droplet size, which prevents phase separation and enhance the bioavailability of active components. The nano sized droplets enhance stability, bioavailability, and uniform dispersion, ensuring better adherence to plant surfaces.35 Zeta potential was measured at -28 mV at room temperature (Figure 4B). Zeta potential represents the surface charge of droplets in a colloidal system and is a key factor in electrostatic behaviour, especially in the systems with a high surface area to volume ratio. The stability of the emulsion was assessed by measuring its zeta potential, as this parameter influences the extent of droplet aggregation.36 Typically, emulsion with zeta potential values ≥±30 mV exhibit excellent stability.37 While the -28 mV value in this study is slightly below this threshold, it still indicates moderate stability, reducing the risk of droplet aggregation or sedimentation of bioactive components over time. The negative charge likely originates from the surfactant system38 or the natural charge of Bt spores39 A stable zeta potential enhances shelf life of the formulation, ensuring the bioactive components remain uniformly distributed over time.

The FTIR spectra presents information regarding the chemical interactions between the components during the formation of Bt-based emulsion (Figure 5). The FTIR spectrum of light liquid paraffin showed C-H stretching between 2953.45-2852.2 cm-1, characteristics of alkanes. C-H bending vibrations were observed between 1457.92-1376.93 cm-1, while the CH2 vibration appeared at 722.211 cm-1, indicating the occurrence of long chain hydrocarbons.40 The Tween 80 presented specific bands at 3428 cm-1 represents O-H stretching, 2923 cm-1 and 2863 cm-1 corresponds to C-H stretching, 1735 cm-1 attributed to C=O stretching, C-H bending at 1460 cm-1, 1352 cm-1 and 1249 cm-1, and C-O stretching at 1107 cm-1. Additionally, C-H deformation peaks noticed at 948 cm-1, 842 cm-1 confirming ester and alkyl functional groups. Span 80 presented with specific bands at 3418.21 cm-1 represents O-H stretching, C–H stretching at 2921 cm-1, 2853 cm-1, and at 1739.48 cm-1 attributed to C=O stretching, 1463.71 cm-1 and 1376.93 cm-1 represents C–H bending, while C-O stretching was observed at 1169.62 cm-1, 1084.76 cm-1, confirming the presence of ester and hydroxyl groups.41 The FTIR spectrum of the glycerol exhibited O-H stretching at 3292 cm-1, while C-H stretching was indicated by peaks within the range of 2879.2 cm-1 to 2930.31 cm-1. Additionally, bending of the C-O-H group was observed between 1400 to 1420 cm-1.42 The FTIR of trehalose displayed a typical vibrational band at 3305 cm-1 indication of -OH and NH groups.43 Additional bands were detected at 2113.6 cm-1 corresponding to stretching vibration of the C-H bond and at 1634.38 cm-1 attributed to the C=O bond.

Figure 5. FTIR spectra of emulsion and its components (Trehalose, Glycerol, Span 80, Tween 80 and Light liquid paraffin)

The spectrum of the water-soluble emulsion formulation showed the characteristic bands of light liquid paraffin, at 2925.48 cm-1 and 2851.24 cm-1 represents C-H stretching and 1460.81cm-1 represents C-H bending, confirm the presence of long hydrocarbon chains, essential for the stability. The presence of glycerol and trehalose was validated by O-H stretching band at 3306.36 cm-1. Tween 80 and Span 80 were identified by shifts at 2925.48 cm-1 and 2851.24 cm-1 represents C-H stretching, 1639.2 cm-1 represents C=O stretching, and 1116.58 cm-1 and 1044.26 cm-1 represents C-O stretching. The prescence of C-O stretching indicate the prescence of ester and ether linkages, supporting the structural integrity of the formulation.

As emulsions are inherently thermodynamically unstable, they gradually separate into their respective oil and aqueous phases over time.44 Several physiochemical mechanisms contribute to this instability, including partial coalescence, coalescence, gravitational separation (creaming), Ostwald ripening, and flocculation.45 In biphasic systems, creaming serves as an indicator of emulsion destabilization.46 The creaming index is widely utilized to assess emulsion stability, where a lower value signifies better resistance to phase separation. Specifically, emulsion with a creaming index between

0% to 5% demonstrate minimal separation and higher stability.47 The creaming index of the developed emulsion formulation was measured at 2.8%, indicating highly stable formulation. This stability ensures good structural integrity, facilitating the effective dispersion of active ingredients in the aqueous medium.

The physical stability of emulsion stored in vials was assessed at ambient conditions and elevated temperature. The emulsions maintained a consistent pH (Figure 6) and odour, as determined by sensory evaluation with no significant variation observed at room temperature. However, slight variation in pH and minor colour changes and minimal phase instability was observed at 37 ± 2 °C. The slight pH fluctuations and minor colour changes at higher temperature suggest some degree of thermal sensitivity, potentially due to ingredient interactions or oxidative changes and also minor phase instability suggest the higher temperature may impact emulsion structural integrity over time. The stable physical stability at ambient condition suggests that the emulsion is well suited for long-term storage at room temperature without compromising its stability or performance.

Figure 6. pH variation of the water-soluble emulsion stored at 25 ± 2 °C and 37 ± 2 °C over a 90 day period

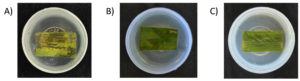

The water-soluble emulsion formulation was applied to maize leaf, and the contact angle was measured. The mean contact angle was measured at an angle of 41.47° on both right and left side (Figure 7). In general, small contact angles (<90°) indicate high wettability, while larger contact angles (>90°) indicate lower wettability.48 The observed reduction in the contact angle suggests an increasing in wettability, leading to improved water retention on leaf surface. This enhanced water retention is beneficial, as it prolongs the longevity of sprays applied to the crop. The extended retention of these sprays on the leaf surface ensures a longer duration of effectiveness in crop protection.

Shelf-life of the formulation

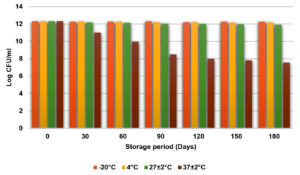

Initially, Log CFU/ml of Bt spores in emulsion was 12.301. The log CFU/ml values of the emulsion remained stable at -20 °C, 4 °C, and 27 ± 2 °C with a slight decline to 12.253, 12.176, and 11.903, respectively, after 180 days, indicating excellent stability at lower temperature and room temperature. However, at 37 ± 2 °C, CFU/ml decline to 7.544 occurred, highlighting poor stability and degradation at higher temperature. Thus, lower temperature (-20 °C and 4 °C) and room temperature (27 ± 2 °C), are ideal for long-term storage, as they effectively maintain the microbial viability (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Effect of storage temperature on the shelf life and viability of emulsion over time (Log CFU/ml)

Bio-efficacy of Bt-based water-soluble emulsion

Bioassay was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of Bt T414 spore crystal mixture, and emulsion formulation. The mortality of larvae following treatment with Bt-based water-soluble emulsion exhibited decreased leaf feeding compared with control (Figure 9). LC50 of the tested population at 7 DAT was found to be 0.017 µg/ml for Bt T414 spore crystal mixture and 0.006 µg/ml for emulsion formulation (Table). These results indicate that the emulsion formulation exhibited enhanced toxicity compared to spore-crystal mixture. When evaluated in terms of potency, the Bt T414 spore-crystal mixture exhibited an activity of 10,352 IU/mg, whereas the Bt T414 emulsion formulation displayed a markedly high potency of 29,333 IU/mg, compared to Dipel (17600 IU/mg potency) which was used as the reference standard. This substantial increase in potency suggest that the emulsion formulation significantly improved the bioavailability and effectiveness of Bt T414 against S. frugiperda larvae.

Table:

Comparative LC50 analysis of Bt emulsion formulation and Bt Spore crystal mixture on neonate S. frugiperda larvae

| No. | Treatment |

LC50 (µg/ml) | Confidence limits (95%) | LC95 (µg/ml) | Confidence limits (95%) | Regression equation | Chi-square | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit |

Upper limit |

||||||

| 1. | Bt emulsion formulation | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.441 | 0.084 | 2.319 | Y = 0.8996x + 7.09195 | 1.1558 |

| 2. | Bt Spore crystal mixture | 0.017 | 0.006 | 0.048 | 1.290 | 0.306 | 5.442 | Y = 0.9457x + 6.6284 | 0.8873 |

| 3. | Bt commercial formulation | 0.010 | 0.003 | 0.033 | 0.470 | 0.168 | 1.314 | Y = 0.8998x + 6.8818 | 2.324 |

Figure 9. Bioassay of S. frugiperda (A) Control, (B) Bt T414 Spore crystal mixture and (C) Bt T414 emulsion formulation

The difference in LC50 between the spore-crystal mixture and emulsion formulation highlights the importance of formulation in increasing the effectiveness of Bt against the insect pest. The reduced Bt content in emulsion formulation to achieve higher larvicidal effects imply that emulsification enhance the insecticidal efficiency of Bt T414. This enhancement is likely due to better dispersion, increased adhesion to treated surfaces and increased ingestion by larva, all of which contributed to improved toxicity. The emulsification process may also enhance the persistence and stability of Bt toxin on foliage, leading to prolonged insecticidal action. The ability to achieve greater efficacy with lower Bt concentration is a notable advantage, as it decreases the requirement and making it more sustainable option for pest control.

The development of Bt-based water-soluble emulsion formulation offers a promising advancement in biopesticide formulation for managing S. frugiperda. The optimized formulation, incorporating mineral oil, surfactant blends, and stabilizers, exhibited excellent physiochemical properties, including stability, nano-sized droplet distribution, and suitable pH. Laboratory bioassays confirmed its high efficacy against S. frugiperda, demonstrating its potential as an environmentally safe alternative to conventional insecticides. The enhanced bioavailability and adherence of the formulation suggest improved field performance making it a viable candidate for large-scale agricultural applications. This study emphasizes the importance of integration of formulation technologies with microbial pesticide to advance sustainable pest management practices in modern agriculture.

Additional file: Figure S1-S2.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the Centre for Plant Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, and the Department of Agricultural Entomology, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, for the infrastructure facility.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

NS and NB conceptualized the study. NB supervised the study. MR, NB and NS applied methodology. MR collected resources, software and wrote the original draft. SH, DJSS, MM, NB, GR, NS and RR wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analysed during this study are included in this manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Ali MA, Abdellah IM, Eletmany MR. Towards sustainable management of insect pests: Protecting food security through ecological intensification. Int J Chem Biochem Sci. 2023; 24(4):386-394.

- Ouaba J, Tchuinkam T, Waimane A, Magara HJO, Niassy S, Meutchieye F. Lepidopterans of economic importance in Cameroon: A systematic review. J Agric Food Res. 2022;8:100286.

Crossref - Kamakshi N, Srujana Y, Krishna TM, Sameera SK, Parveen SI. Mitigation of exotic fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) on dryland Sorghum in Southern parts of India. Int J Trop Insect Sci. 2023;43(4):1169-1177.

Crossref - Van den Berg J, Brewer MJ, Reisig DD. A special collection: Spodoptera frugiperda (fall armyworm): Ecology and management of its world-scale invasion outside of the Americas. J Econ Entomol. 2022;115(6):1725-1728.

Crossref - Goergen G, Kumar PL, Sankung SB, Togola A, Tamò M. First report of outbreaks of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae), a new alien invasive pest in West and Central Africa. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0165632.

Crossref - Overton K, Maino JL, Day R, et al. Global crop impacts, yield losses and action thresholds for fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda): A review. Crop Prot. 2021;145:105641.

Crossref - Deshmukh SS, Prasanna BM, Kalleshwaraswamy CM, Jaba J, Choudhary B. Fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda). In Omkar (eds.). Polyphagous Pests of Crops. Springer, Singapore. 2021:349-372.

Crossref - Chimweta M, Nyakudya IW, Jimu L, Bray Mashingaidze A. Fall armyworm [Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith)] damage in maize: management options for flood-recession cropping smallholder farmers. Int J Pest Manag. 2020;66(2):142-154.

Crossref - Kumela T, Simiyu J, Sisay B, et al. Farmers’ knowledge, perceptions, and management practices of the new invasive pest, fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) in Ethiopia and Kenya. Int J Pest Manag. 2019;65(1):1-9.

Crossref - Ali S, Ullah MI, Sajjad A, Shakeel Q, Hussain A. Environmental and health effects of pesticide residues. In: Amuddin, Ahamed MI, Lichtfouse E. (eds.). Sustainable Agriculture Reviews. 2021;48:311-336.

Crossref - Gutierrez-Moreno R, Mota-Sanchez D, Blanco CA, et al. Field-evolved resistance of the fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to synthetic insecticides in Puerto Rico and Mexico. J Econ Entomol. 2019;112(2):792-802.

Crossref - Khursheed A, Rather MA, Jain V, et al. Plant based natural products as potential ecofriendly and safer biopesticides: A comprehensive overview of their advantages over conventional pesticides, limitations and regulatory aspects. Microb Pathog. 2022;173(Pt A):105854.

Crossref - Ruiu L. Microbial biopesticides in agroecosystems. Agronomy. 2018;8(11):235.

Crossref - Aswathi N, Balakrishnan N, Srinivasan T, Kokiladevi E, Raghu R. Diversity of Bt toxins and their utility in pest management. Egypt J Biol Pest Control. 2024;34(1):40.

Crossref - Lu K, Gu Y, Liu X, Lin Y, Yu XQ. Possible insecticidal mechanisms mediated by immune-response-related Cry-binding proteins in the midgut juice of Plutella xylostella and Spodoptera exigua. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65(10):2048-2055.

Crossref - Ragasruthi M, Balakrishnan N, Murugan M, Swarnakumari N, Harish S, Sharmila DJS. Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt)-based biopesticide: Navigating success, challenges, and future horizons in sustainable pest control. Sci Total Environ. 2024;954:176594.

Crossref - Reyaz AL, Balakrishnan N, Udayasuriyan V. Genome sequencing of Bacillus thuringiensis isolate T414 toxic to pink bollworm (Pectinophora gossypiella Saunders) and its insecticidal genes. Microb Pathog. 2019;134:103553.

Crossref - Gothandaraman R, Venkatasamy B, Thangavel T, Eswaran K, Subbarayalu M. Molecular characterization and toxicity evaluation of indigenous Bacillus thuringiensis isolates against key lepidopteran insect pests. Egypt J Biol Pest Control. 2022;32(1):143.

Crossref - Yaakov N, Kottakota C, Mani KA, et al. Encapsulation of Bacillus thuringiensis in an inverse Pickering emulsion for pest control applications. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2022;213:112427.

Crossref - Hierrezuelo JM, Molina-Bolivar JA, Ruiz CC. An energetic analysis of the phase separation in non-ionic surfactant mixtures: the role of the headgroup structure. Entropy. 2014;16(8):4375-4391.

Crossref - McClements DJ. Biopolymers in Food Emulsions. In: Kasapis S, Norton IT, Ubbink JB, eds. Modern Biopolymer Science: Bridging the Divide Between Fundamental Treatise and Industrial Application. Academic Press; 2009:129-166.

Crossref - Bakr SZ, Alrahman SSA. Effect of thermal storage on the stability and efficacy of bioformulation bicont-t against fig moth larvae Ephestia cautella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Int J Agricult Stat Sci. 2021;17(1):2221-2228.

- Pipe CJ, Majmudar TS, McKinley GH. High shear rate viscometry. Rheol Acta. 2008;47(5):621-642.

Crossref - Petrovic LB, Sovilj VJ, Katona JM, Milanovic JL. Influence of polymer-surfactant interactions on o/w emulsion properties and microcapsule formation. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2010;342(2):333-339.

Crossref - Badruddoza AZM, Yeoh T, Shah JC, Walsh T. Assessing and Predicting Physical Stability of Emulsion-Based Topical Semisolid Products: A Review. J Pharm Sci. 2023;112(7):1772-1793.

Crossref - Lawrence MJ, Rees GD. Microemulsion-based media as novel drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2000;45(1):89-121.

Crossref - Barbosa FG, Ribeaux DR, Rocha T, et al. Biosurfactants: sustainable and versatile molecules. J Braz Chem Soc. 2022;33(8):870-893.

Crossref - Ghaicha L, Leblanc RM, Villamagna F, Chattopadhyay AK. Monolayers of mixed surfactants at the oil-water interface, hydrophobic interactions, and stability of water-in-oil emulsions. Langmuir. 1995;11(2):585-590.

Crossref - Patel H, Raval G, Nazari M, Heerklotz H. Effects of glycerol and urea on micellization, membrane partitioning and solubilization by a non-ionic surfactant. Biophys Chem. 2010;150(1-3):119-128.

Crossref - Ghosh S, Basistha B, Ghosh AK. Trehalose, an anti-stress disaccharide protecting life-forms in adverse conditions. In Chakraborty B, Chakraborty C (eds.). Annual Review of Plant Pathology. 2014;6:155-188.

- El-Bendary MA, Elsoud MMA, Hamed SR, Mohamed SS. Optimization of mosquitocidal toxins production by Bacillus thuringiensis under solid state fermentation using Taguchi orthogonal array. Acta Biol Szeged. 2017;61(2):135-140.

- Goodarzi F, Zendehboudi S. A comprehensive review on emulsions and emulsion stability in chemical and energy industries. Can J Chem Eng. 2019;97(1):281-309.

Crossref - Marhamati M, Ranjbar G, Rezaie M. Effects of emulsifiers on the physicochemical stability of Oil-in-water Nanoemulsions: A critical review. J Mol Liq. 2021;340:117218.

Crossref - Kumar A, Kanwar R, Mehta SK. Nanoemulsion as an effective delivery vehicle for essential oils: Properties, formulation methods, destabilizing mechanisms and applications in agri-food sector. Next Nano. 2024;7:100096.

Crossref - Ding X, Gao F, Cui B, et al. The key factors of solid nanodispersion for promoting the bioactivity of abamectin. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2024;201:105897.

Crossref - Kumar N, Mandal A. Surfactant stabilized oil-in-water nanoemulsion: stability, interfacial tension, and rheology study for enhanced oil recovery application. Energy Fuel. 2018;32(6):6452-6466.

Crossref - Lunardi CN, Gomes AJ, Rocha FS, Tommaso J De, Patience GS. Experimental methods in chemical engineering: Zeta potential. Can J Chem Eng. 2021;99(3):627-639.

Crossref - Tian Y, Chen L, Zhang W. Influence of ionic surfactants on the properties of nanoemulsions emulsified by nonionic surfactants span 80/tween 80. J Dispers Sci Technol. 2016; 37(10):1511-1517.

Crossref - Chung E, Kweon H, Yiacoumi S, et al. Adhesion of spores of Bacillus thuringiensis on a planar surface. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(1):290-296.

Crossref - Lana K, Susilo W, Widarto, Dharma PNM, Argo S. Characteristics of paraffin shielding of kartini reactor, Yogyakarta. ASEAN J Sci Technol Dev. 2020;35(3):195-198.

Crossref - Fu X, Kong W, Zhang Y, Jiang L, Wang J, Lei J. Novel solid-solid phase change materials with biodegradable trihydroxy surfactants for thermal energy storage. RSC Adv. 2015;5(84):68881-68889.

Crossref - Danish M, Mumtaz MW, Fakhar M, Rashid U. Response surface methodology based optimized purification of the residual glycerol from biodiesel production process. Chiang Mai J Sci. 2017;44(4):1570-1582.

- Muhoza B, Xia S, Wang X, Zhang X. The protection effect of trehalose on the multinuclear microcapsules based on gelatin and high methyl pectin coacervate during freeze-drying. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;105:105807.

Crossref - Nie C, Han G, Ni J, et al. Stability dynamic characteristic of oil-in-water emulsion from alkali-surfactant-polymer flooding. ACS Omega. 2021;6(29):19058-19066.

Crossref - Ravera F, Dziza K, Santini E, Cristofolini L, Liggieri L. Emulsification and emulsion stability: The role of the interfacial properties. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;288:102344.

Crossref - Singh Y, Meher JG, Raval K, et al. Nanoemulsion: Concepts, development and applications in drug delivery. J Contr Release. 2017;252:28-49.

Crossref - Karaca AC, Nickerson MT, Low NH. Lentil and chickpea protein-stabilized emulsions: optimization of emulsion formulation. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(24):13203-13211.

Crossref - Yuan Y, Lee TR. Contact angle and wetting properties. In Bracco G, Holst B. (eds.). Surface Science Techniques. Springer, Berlin. 2013;51:3-34.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.