ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

Fleas of the genus Ctenocephalides that infest cats and dogs are known to harbor various pathogenic bacteria with potential zoonotic importance. This study aimed to isolate, characterize, and identify bacterial species from the gastrointestinal tracts of Ctenocephalides felis and Ctenocephalides canis using biochemical profiling, antibiotic susceptibility testing, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. A total of ten bacterial isolates were obtained, showing different biochemical and antibiotic resistance profiles. Biochemical identification revealed the presence of Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Francisella, and Sphingomonas species, while molecular identification indicated variations at both the genus and species levels. Notably, isolates from C. canis exhibited higher resistance compared to those from C. felis, with Benzylpenicillin being the most resistant antibiotic. These findings highlight the species divergence and antibiotic resistance patterns of flea-associated bacteria, emphasizing their potential role in zoonotic transmission and the need for integrated monitoring of flea-borne pathogens.

Pure Culture, Bacteria, Ctenocephalides Felis, Ctenocephalides Canis

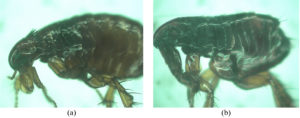

Companion animals such as dogs and cats play an essential role in human society, offering emotional and social benefits but also serving as potential sources of zoonotic infections.1,2 Their close association with humans increases the risk of exposure to ectoparasites, particularly fleas of the genus Ctenocephalides, which are among the most prevalent and medically significant parasites affecting domestic animals worldwide.3 Ctenocephalides felis primarily infests cats, while Ctenocephalides canis is more frequently found on dogs.4-6 Although these two species are morphologically similar, they differ in host specificity, ecological adaptation, and microbial associations.7

Fleas are well-documented vectors of various pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and rickettsiae, that can cause diseases in animals and humans. Beyond their external role as vectors, the gastrointestinal tract of fleas constitutes a crucial internal niche for microbial colonization, survival, and transmission. Bacteria residing in this compartment may interact with both the flea host and ingested blood, influencing the flea’s physiology and its competence as a disease vector.8-11 Previous studies have identified several pathogenic bacterial taxa in fleas, such as Bartonella henselae, Rickettsia felis, and Francisella tularensis, highlighting their role in zoonotic cycles.8,9 However, most of these studies have focused on metagenomic detection, with limited information available on the biochemical traits and antibiotic resistance patterns of individual bacterial isolates within flea species.

Understanding the biochemical and molecular characteristics of flea-associated bacteria is vital for evaluating their pathogenic potential and antimicrobial resistance, particularly in the context of the growing global concern over antibiotic-resistant zoonotic microorganisms. Comparative investigations between C. felis and C. canis may further reveal species-specific bacterial assemblages that reflect host preference, ecological behavior, and differing transmission capacities.12-14

Therefore, the present study aims to isolate, characterize, and identify bacterial species from the gastrointestinal tracts of Ctenocephalides felis and Ctenocephalides canis through biochemical profiling, antibiotic susceptibility testing, and 16S rRNA gene-based molecular analysis (Figure 1). By integrating phenotypic and genotypic approaches, this work seeks to provide insights into the microbial diversity, antibiotic resistance, and potential zoonotic relevance of bacteria associated with cat and dog fleas.

Samples

Adult fleas (Ctenocephalides felis and Ctenocephalides canis) were collected from domestic dogs and cats in Minahasa Regency (1°222 443 N, 124°332 523 E to 1°012 113 N, 125°042 213 E) and Tomohon City (1°152 N, 124°502 E), North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Thirty flea specimens were obtained from fifteen animals of each host species using sterile forceps. Live specimens were placed in sterile containers and transported immediately to the laboratory for bacterial isolation. For molecular analysis, representative samples were preserved in 95% ethanol and stored at -20 °C until DNA extraction.

Research Procedure

Bacterial isolation

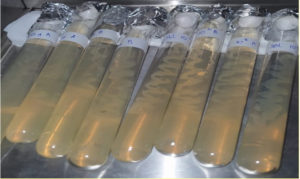

Each flea was dissected aseptically on a sterile Petri dish under a stereomicroscope. The digestive tract was excised and streaked onto nutrient agar (NA) plates using a sterile inoculating loop. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 hours. Colonies with distinct morphology were subcultured three times on nutrient agar slants to obtain pure cultures (Figure 2). Stable isolates were selected for further biochemical and molecular analyses.

Figure 2. Pure culture of bacterial isolates from the digestive tract Ctenocephalides felis and Ctenocephalides canis

Biochemical analysis with Vitect 2 compact

Biochemical characterization and identification were conducted using the Vitek 2 Compact automatic identification instrument (Figure 3). The analysis was conducted in a certified medical laboratory, the Laboratory of Dr. Kandouw Government General Hospital, Manado, North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Vitek 2 Compact is an automatic microorganism identification tool. The latest technology using Vitek 2 Compact consists of three stages of examination for biochemical identification and antibiotic sensitivity. Vitect2 Compact has been validated and interpreted according to the Clinical Laboratory Standard International (CLSI).15,16 Before biochemical identification, Gram staining was performed on each isolate. The three stages are preparation or standardization of inoculum turbidity, data entry with a barcode system, and insertion of an identification card into the device.

Furthermore, the device will automatically carry out the entire process of inoculation, incubation, reading, validation, and interpretation of results. Furthermore, the completed examination will automatically produce a printout, while the system will automatically discard the ID/AST (Identification/Antimicrobial Sensitivity Test) card. The principle of automatic identification is to use an identification card; on the card, there is a well or a biochemical test medium modified for rapid bacterial identification. The testing procedure with the Vitek 2 Compact device starts from the gram test, card selection, and making bacterial suspensions according to the McFarland standard and identification using the device until the identification results sheet is issued. Based on the theory that the results obtained in identification with the Vitek 2 Compact are expressed in percentages for the correctness of the identified organisms (Table 1).16,17

A total of 47 biochemical test parameters were used for each bacterial isolate. The biochemical test result indicators are positive (+) and/or negative (-) (Table 2).

Table (1):

VITEK 2 Compact Output Analysis Standard

Confidence Level |

Choice |

% Probability |

|---|---|---|

Excellent |

1 |

96 to 99 |

Very Good |

1 |

93 to 95 |

Good |

1 |

89 to 92 |

Acceptable |

1 |

85 to 88 |

Table (2):

Biochemical parameters in VITEK 2 Compact

No. |

Symbol |

Chemical nomenclature |

|---|---|---|

1 |

H2S |

H2S Production |

2 |

BGLU |

Beta-Glucose |

3 |

BGURr |

Beta-Glucuronidase |

4 |

PyrA |

L-Pyrrolydonyl-Arylamidase |

5 |

SAC |

Saccharose/Sucrose |

6 |

dTRE |

D-Trehalose |

7 |

dMAN |

D-Mannitol |

8 |

APPA |

Ala-Phe-Pro Arylamidase |

9 |

ILATk |

L-Lactate alkalinization |

10 |

GlyA |

Glycine Arylamidase |

11 |

O129r |

O/129 Resistance |

12 |

dMAL |

D-Maltose |

13 |

LIP |

Lipase |

14 |

dTAG |

D-Tagatosa |

15 |

AGLU |

Alpha-Glucosidase |

16 |

ODC |

Ornithine Decarboxylase |

17 |

dGLU |

D-Glucose |

18 |

dMNE |

D-Mannose |

19 |

TyrA |

Tyrosine Arylamidase |

20 |

CIT |

Citrate/Sodium |

21 |

dCEL |

D-Cellobiose |

22 |

GGT |

Gamma-Glutamyl-Transferase |

23 |

BXYL |

B-Xylose |

24 |

URE |

Urease |

25 |

ProA |

L-Proline Arylamidase |

26 |

GGAA |

Glu-Gly-Arg-Arylamidase |

27 |

PLE |

Palatinose |

28 |

AGLTp |

Glutamyl Arylamidase Pna |

29 |

SUCT |

Succinate alkalinization |

30 |

ELLM |

Ellman |

31 |

BGAL |

Beta-Galactosidase |

32 |

OFF |

Fermentation Glucose |

33 |

LDC |

Lysine Decarboxylase |

34 |

IMTLa |

L-Malate assimilation |

35 |

IARL |

L-Arabitol |

36 |

NAGA |

Beta-N-Acetyl |

37 |

IHISa |

Histidine assimilation |

38 |

BAlap |

Beta-Alanine Arylamidase |

39 |

dSOR |

D-Sorbitol |

40 |

5KG |

5-Keto-D-Gluconate |

41 |

PHOS |

Phosphatase |

42 |

ADO |

Adonitol |

43 |

BNAG |

Beta-N-Acetyl-Glucosaminidase |

44 |

ILATa |

L-Lactate assimilation |

45 |

MNT |

Malonate |

46 |

AGAL |

Alpha-Galactosidase |

47 |

CMT |

Coumarate |

Antibiotic resistance test

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) was conducted concurrently with biochemical identification using the Vitek 2 Compact system. A panel of 21 antibiotics representing different classes (β-lactams, aminoglycosides, macrolides, tetracyclines, glycopeptides, and fluoroquinolones) was employed. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were automatically calculated by the instrument. Resistance and susceptibility interpretations were determined according to CLSI (2021) breakpoints. Antibiotic resistance was analyzed using variance and Tukey’s test.6,17

Molecular identification of pure cultures of bacteria

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA from pure bacterial cultures was extracted using the Quick-DNA™ Fungal/Bacterial Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 50-100 mg of bacterial cells were lysed in BashingBead™ buffer and processed in a bead beater at maximum speed for 5 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min, and the supernatant was purified through a Zymo-Spin™ column. DNA was eluted in 100 µL of elution buffer and stored at -20 °C for PCR amplification.18,19

16S rRNA amplification and sequencing

16S rRNA gene amplification was performed using primers: 16sA (5’CGC CTG TTT AAC AAA AAC AT 3′) (Forward), 16sB2 (5’TTT AAT CCA ACA TCG AGG 3′) (Reverse). PCR amplification was performed with 2x PCR components MyTaq HS Red Mis Bioline 25 µl; 10 pmol primers consisting of 1 µl forward primer, 1 µl reverse primer, 2 µl DNA template, and 21 µl ddH2O. At the same time, the PCR conditions used a 35x cycle with Denaturation of 94 °C for 70 seconds, annealing of 55 °C for 35 seconds, extension of 70 °C for 40 seconds, and a final extension of 70 °C for 40 seconds. Amplicon visualization used the 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis method. The PCR products were then sent to the sequencing service company 1st BaseTM in Singapore for sequencing using the Sanger method.18

Analysis of sequencing results

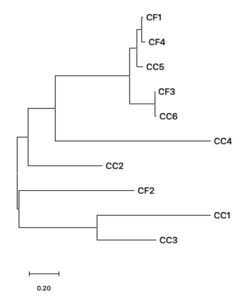

Raw sequences were trimmed and assembled using MEGA version 12. Consensus sequences were aligned using BLASTn (National Center for Biotechnology Information, NCBI) to determine taxonomic identity based on sequence similarity. Phylogenetic trees were constructed in MEGA 12 using the Neighbor-Joining and Minimum Evolution methods with 1,000 bootstrap replications. Sequences showing ≥97% identity were considered to belong to the same bacterial species.18,19

Bacterial Isolation

A total of ten pure bacterial isolates were successfully recovered from the gastrointestinal tracts of Ctenocephalides felis (four isolates) and Ctenocephalides canis (six isolates). All isolates exhibited distinct colony morphologies and stable growth following three successive subcultures. The higher bacterial diversity observed in C. canis may reflect its broader host interactions and greater environmental exposure, consistent with previous reports suggesting that C. canis exhibits higher microbial carriage variability compared to C. felis.

Biochemical identification and characterization

Biochemical profiling using the Vitek 2 Compact system revealed clear interspecific differences between bacterial isolates from C. felis and C. canis. Isolates from C. felis predominantly belonged to the genus Staphylococcus (e.g., S. sciuri, S. lentus), whereas isolates from C. canis included Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas fluorescens, and Sphingomonas paucimobilis (Table 3). The presence of Staphylococcus spp. in both flea species is noteworthy, as these bacteria are known for their adaptability and frequent association with skin and mucosal surfaces of mammals. However, the occurrence of Francisella tularensis like isolates in C. felis and Pseudomonas spp. in C. canis indicates species-specific microbial assemblages. This variation could be influenced by physiological differences between the flea hosts, their feeding patterns, or the microbial composition of their respective mammalian hosts. These findings reinforce the role of the flea gastrointestinal tract as an ecological reservoir supporting taxonomically diverse bacteria. Such diversity may contribute to the fleas’ competence as potential vectors of opportunistic and pathogenic microorganisms.

Table (3):

Results of biochemical tests of bacterial isolates from C. felis and C. canis

| No. | Isolate | Positive Biochemical Test Results | Number of Biochemical Parameters tested | Species/Gram Staining | % Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctenocephalides felis |

|||||

| 1 | CF1 | AMY, dRIB, dXYL, BGURr, NAG, dMAL, PHOS, BGUR dan BACi | 43 | Staphylococcus sciuri/ + | 97 |

| 2 | CF2 | AMY, dRIB, OPTO, NC6.5, dXYL, dMANE, SAL, NAG, dMNE, SAC, PLYB, dMAL, MBdG, dTRE, BACi | 47 | Staphylococcus lentus/ + | 96 |

| 3 | CF3 | ProA, PyrA | 47 | Francisella tularensis/ – | 93 |

| 4 | CF4 | dRIB, NOVO, OPTO, dXYL, LAC, dMAN, URE, SAC, dMAL, dTRE, BGUR | 43 | Staphylococcus arlettae/ + | 94 |

| Ctenocephalides canis |

|||||

| 1 | CC1 | AMY, LeuA, dRIB, dXYL, BGURr, NAG, dMAL, PHOS, BGUR dan BACi, ADH2s | 47 | Staphylococcus aureus/ + | 96 |

| 2 | CC2 | AMY, AlaA dRIB, OPTO, PIPLC, NC6.5, dXYL, dMANE, SAL, NAG, dMNE, SAC, PLYB, dMAL, MBdG, dTRE, BACi | 43 | Staphylococcus aureus/ + | 95 |

| 3 | CC3 | APPA, ProA, PyrA, dGLU, BGAL, BGUR | 47 | Staphylococcus haemolyticus/ +

|

96 |

| 4 | CC4 | AMY, APPA, dRIB, NOVO, OPTO, dXYL, LAC, dMAN, URE, SAC, dMAL, dTRE, BGUR, BACl | 43 | Pseudomonas fluorescens/ – | 90 |

| 5 | CC5 | AMY, APPA, dRIB, NOVO, OPTO, dXYL, LAC, dMAN, URE, NAG, SAC, dMAL, dTRE, BGUR, BACl | 47 | Pseduomonas stutzeri/ – | 90 |

| 6 | CC6 | LeuA, dRIB, NOVO, OPTO, dXYL, LAC, dMAN, URE, SAC, dMAL, dTRE, BGUR, BACl | 43 | Sphingomonas paucimobilis/ – | 94 |

Antibiotic resistance test

The results of antibiotic resistance tests of four Ctenocephalides felis bacterial isolates and six Ctenocephalides canis bacterial isolates showed different resistance and susceptibility responses. A total of 21 types of antibiotics were used to test the resistance of bacterial isolates. Bacterial isolates CF1, CF2, CF3 only showed resistance to Benzylpenicillin (MIC: <0.03; <0.5; <0.03; <0.03). Isolate CF4 showed resistance to Benzylpenicillin and Vancomycin (MIC: <0.03 and <0.05) (Appendix 1).

Antibiotic resistance test on C. canis isolates using 20 types of antibiotics. Isolate CC1 showed resistance to Benzylpenicillin (MIC: >0.5), Oxacillin (MIC: >4), and Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole (MIC: >320). Isolate CC2 showed resistance to Cefazolin (MIC: >64) and Aztreonam (MIC: 32). Isolate CC3 showed resistance to Benzylpenicillin (MIC: >0.5), Oxacillin (MIC: >4) and Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole (MIC: 80). Isolate CC4 did not show resistance to the antibiotics tested. Isolate CC5 showed resistance to Cefazolin (MIC: <4) and Aztreonam (MIC: >64). Isolate CC6 showed resistance to Cefazolin (MIC: >64) and Aztreonam (MIC: 32) (Appendix 2).

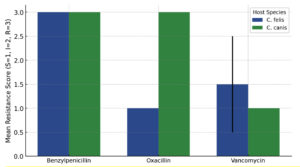

Analysis of antibiotic susceptibility revealed distinct resistance profiles among bacterial isolates from Ctenocephalides felis and C. canis (Table 4). Overall, isolates from both flea species exhibited high resistance to Benzylpenicillin, with all tested isolates classified as resistant (score = 3), indicating no interspecific variation for this antibiotic. In contrast, a pronounced difference was observed for Oxacillin resistance. ANOVA indicated a statistically significant variation between the two flea species (F = ∞, p < 0.001), with isolates from C. canis showing complete resistance (score = 3) whereas those from C. felis were fully susceptible (score = 1). This suggests species-specific bacterial communities or differential exposure to β-lactam antibiotics in their respective hosts. For Vancomycin, no significant difference was detected between C. felis and C. canis (p = 0.356), though C. felis isolates displayed slightly higher mean resistance scores (1.75 ± 0.50) compared to C. canis (1.33 ± 0.52). These findings indicate that while both flea species harbor bacteria with similar glycopeptide sensitivity, β-lactam resistance profiles vary markedly between hosts.

Table (4):

Analysis of variance of antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic |

Mean ± SD (C. felis) |

Mean ± SD (C. canis) |

F-statistic |

p-value |

Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Benzylpenicillin |

3.00 ± 0.00 |

3.00 ± 0.00 |

– |

– |

ns |

Oxacillin |

1.00 ± 0.00 |

3.00 ± 0.00 |

∞ |

0.0000 |

* |

Vancomycin |

1.75 ± 0.50 |

1.33 ± 0.52 |

1.00 |

0.356 |

ns |

Description: S = 1, I = 2, R = 3; * = significant (p < 0.05); ns = no significant

Oxacillin showed a significant difference in resistance (p < 0.001) between C. felis and

C. canis. Isolates from C. canis had higher resistance to Oxacillin than C. felis. Benzylpenicillin could not be analyzed because all isolates showed the same resistance pattern (R), so the variance = 0. Vancomycin showed no significant difference (p > 0.05) between the two tick species (Table 5).

Table (5):

Differences in resistance levels

Antibiotic |

F-statistic |

P-value |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

Benzylpenicillin |

– |

– |

Cannot be calculated (all values are the same = R, no variation). |

Oxacillin |

¥ |

0.0000 |

The differences are very significant between C. felis (all S) and C. canis (all R). |

Vancomycin |

1.00 |

0.356 |

Not significant; resistance was similar between the two species. |

Oxacillin menunjukkan perbedaan resistansi yang signifikan (p < 0.001) antara C. felis dan C. canis. Isolat dari C. canis memiliki resistansi yang lebih tinggi terhadap Oxacillin dibanding C. felis. Benzylpenicillin tidak dapat dianalisis karena semua isolat menunjukkan pola resistansi yang sama (R), sehingga varians = 0. Vancomycin menunjukkan tidak ada perbedaan signifikan (p > 0.05) antara kedua spesies kutu. Bars represent the mean (±SD) resistance scores for each antibiotic, where S = 1, I = 2, and R = 3. The two flea species exhibited distinct resistance profiles, with C. canis showing significantly higher resistance to Oxacillin (p < 0.001), as indicated by the red asterisk. No significant differences were observed for Benzylpenicillin or Vancomycin. These results highlight host-specific variations in bacterial resistance patterns associated with different flea species (Figure 3).

Molecular identification of bacterial isolates

The results of molecular identification using the 16S rRNA gene showed the similarity of each species of bacterial isolates obtained from C. felis and C. canis, which differed from the results of biochemical tests. Each 16S rRNA gene sequence of bacterial isolates from C. felis and C. canis was aligned with BLAST on the NCBI site. Based on the percent identity obtained, CF2 showed similarity to Achromobacter insolitus with a percent identity of 85.96%, while CF4 showed similarity to Sphingobacterium faecium with the highest percent identity of 98.76%. On the other hand, isolate CC1 showed similarity to Bacillus sp. (in: firmicutes) with the highest percent identity of 100%. In comparison, isolate CC4 showed similarity to Bacillus paralicheniformis, with the lowest percent identity being 94.45% (Table 6).

Table (6):

Identical species of 16S rRNA gene sequences of bacterial isolates C. felis and C. canis using the NCBI BLAST method

| No. | Isolate | Species termirip hasil BLAST NCBI | Perc. Ident | Accession Number | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctenocephalides felis |

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi |

||||

| 1 | CF1 | Pedobacter suwonensis | 88.33% | CP031708.1 | |

| 2 | CF2 | Achromobacter insolitus | 85.96% | CP038034.1 | |

| 3 | CF3 | Pseudochrobactrum sp. XF203 | 96.28% | CP084392.1 | |

| 4 | CF4 | Sphingobacterium faecium | 98,76% | CP123861.1 | |

| Ctenocephalides canis |

|||||

| 1 | CC1 | Bacillus sp. (in: firmicutes) | 100% | PQ097125.1 | |

| 2 | CC2 | Gamma proteobacterium | 97.35% | ON406394.1 | |

| 3 | CC3 | Enterobacter cloacae | 100% | MT613361.1 | |

| 4 | CC4 | Bacillus paralicheniformis | 94.45% | CP043501.1 | |

| 5 | CC5 | Sphingobacterium sp. | 99.10% | CP079104.1 | |

| 6 | CC6 | Pseudochrobactrum sp. | 97.53% | CP084392.1 | |

To obtain phylogenetic relationships, the 16S rRNA gene sequences of bacterial isolates from C. felis and C. canis were used to construct a phylogenetic tree. The phylogenetic construction produced two main monophyletic groups (Figure 4). Based on the phylogenetic tree formed, three bacterial isolates were in the same monophyletic group, namely CC2, CC1, and CC3. Thus, the three isolates have a close relationship. At the same time, the CC2 isolate is in its monophyletic group. CC4 is in the same group as CF1, CF4, CF3, and CC6, but not at the same node. This means that CC2 and CC4 have genetic variations compared to CF3, CC6, CC5, CF4 and CF1 (Figure 4). The results of this study indicate that bacterial isolates in both C. canis and C. felis have high species divergence.

The combined biochemical, antimicrobial, and molecular data from this study reveal distinct and ecologically meaningful differences in the bacterial assemblages associated with Ctenocephalides felis and C. canis. Phenotypically, isolates from both species exhibited broad carbohydrate metabolism and enzymatic versatility, including the ability to utilize D-amygdalin, D-ribose, D-galactose, D-xylose, and N-acetylglucosamine.20 However, specific enzymatic activities—such as leucine arylamidase and phosphatidylinositol phospholipase C in C. canis isolates, and L-proline and alanine arylamidases in C. felis suggest niche-driven adaptations to differing gut environments or host-derived nutritional substrates.21 Such host-specific biochemical patterns align with previous metagenomic reports showing that flea microbiota composition varies according to host species, geography, and blood meal origin.22-25

Molecular identification based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing revealed that the bacterial isolates belonged to multiple genera, including Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Sphingomonas, and Francisella, thereby extending the known microbial diversity of flea-associated bacteria.26 Several discrepancies between biochemical and molecular identifications were observed, for instance where isolates biochemically classified as Staphylococcus were genetically aligned with Achromobacter or Sphingobacterium.27-29 These inconsistencies highlight the limitations of phenotypic methods such as VITEK 2 for environmental or host-associated isolates, due to restricted clinical reference databases and phenotypic plasticity within bacterial taxa.30-33 Such findings underscore the necessity of a polyphasic taxonomic approach integrating phenotypic, genotypic, and phylogenetic analyses to achieve accurate identification, as has been emphasized in comparative microbiome studies of arthropod vectors.34-36

The antibiotic susceptibility data demonstrated marked interspecific variation. All isolates were resistant to Benzylpenicillin, confirming the ubiquity of β-lactam resistance, while ANOVA revealed a significant difference in Oxacillin resistance (p < 0.001) between the two flea species.37,38 Isolates from C. canis were consistently resistant, whereas those from C. felis were fully susceptible. This divergence likely reflects differential exposure to antimicrobial residues through host blood or environmental contact, leading to distinct microbial selection pressures. Such results are consistent with reports that coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) species, including S. sciuri and S. lentus, can act as reservoirs of β-lactamase and mecA resistance determinants transferable to more virulent species like S. aureus.39,40 The presence of S. arlettae and S. haemolyticus both recognized for their genomic plasticity and multidrug-resistance further reinforces the fleas’ potential role as carriers of resistance genes in domestic ecosystems.

Among Gram-negative isolates, Pseudomonas fluorescens, P. stutzeri, and Sphingomonas paucimobilis were recovered predominantly from C. canis. Although typically environmental, these bacteria have been associated with opportunistic and nosocomial infections, particularly in immunocompromised hosts.38 Their presence within flea gastrointestinal tracts may therefore represent an indirect but significant link between environmental microbial pools and companion animals, suggesting that fleas could serve as intermediate reservoirs facilitating the persistence and potential transfer of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria across ecological boundaries. The detection of Francisella tularensis related sequences in C. felis isolates also warrants attention, as it implies the coexistence of potentially pathogenic taxa within the flea microbiome that might interact with symbiotic or commensal populations.30-33

The integrated interpretation of biochemical, molecular, and resistance data provides a more holistic understanding of the microbial ecology of C. felis and C. canis. The metabolic flexibility observed among isolates likely confers survival advantages within the nutrient-variable flea gut, while differences in resistance profiles suggest that the microbiota of C. canis is under greater selective pressure, possibly due to repeated environmental exposure or differences in host pharmacological backgrounds. Furthermore, the observed discrepancies between phenotypic and genotypic identifications support the hypothesis that environmental bacterial isolates within fleas are evolving under unique selective regimes, potentially facilitating horizontal gene transfer events that contribute to antimicrobial resistance dissemination. This interpretation is consistent with the broader One Health perspective, which posits that arthropods, particularly ectoparasites, can function as micro-reservoirs within the interconnected network of human, animal, and environmental health.

Collectively, these findings advance our understanding of the complex microbial ecology of cat and dog fleas. They reveal that flea-associated bacteria are metabolically diverse, taxonomically heterogeneous, and variably resistant to clinically relevant antibiotics. Importantly, they suggest that fleas may represent overlooked but ecologically significant reservoirs and vectors of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. Future research should employ whole-genome sequencing and resistome analysis to elucidate the genetic mechanisms underlying these resistance patterns, trace the mobility of resistance genes across taxa, and quantify the potential contribution of fleas to AMR transmission within domestic and public health contexts.

This study provides integrative evidence that the gastrointestinal bacterial communities of Ctenocephalides felis and C. canis differ substantially in their biochemical characteristics, molecular composition, and antimicrobial resistance profiles. The bacterial isolates displayed host-specific metabolic adaptations and variable antibiotic resistance, particularly toward β-lactam antibiotics, with C. canis associated isolates exhibiting broader resistance patterns. Molecular identification through 16S rRNA sequencing confirmed a diverse microbiota encompassing both opportunistic and environmental taxa, including Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Sphingomonas, and Francisella species. The coexistence of metabolically versatile and multidrug-resistant bacteria within these flea species suggests that fleas may act as ecological reservoirs and potential vectors for antimicrobial resistance within domestic and peri-domestic environments. These findings underscore the importance of including ectoparasites in One Health surveillance frameworks and highlight the need for genomic-based approaches to characterize the resistome and mobile genetic elements contributing to bacterial persistence and resistance dissemination across host species.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful to the Directorate of Research, Technology and Community Service, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology, Republic of Indonesia, for funding this research. The authors are also thankful to the management and staff of the Clinical Laboratory of Dr. Kandow Government General Hospital, Manado, North Sulawesi, for providing laboratory analysis facilities, and the Head of the Biology Laboratory, Faculty of Mathematics, Natural Sciences and Earth Sciences, Manado State University, for allowing the use of the laboratory for bacterial isolation and molecular identification of bacterial isolates.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

DVR, MYS, and OAW conceptualized the study. DVR and JSBT applied methodology. DVR, OAW, and MYS investigated the study. MYS and JSBT performed data and formal analysis. DVR and JSBT collected the resources. DVR and MYS wrote the original draft. MYS JSBT and OAW wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript, and HHA performed supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

FUNDING

This study was funded by the DRTPM Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia in 2024, under contract number 084/ES/PG.02.00.PL/2024, through the Fundamental Research scheme.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

- Kumar A, Rana T, Bhatt S, Kumar A. Insecta Infestations in Dogs and Cats. In: Rana T eds. Principles and Practices of Canine and Feline Clinical Parasitic Diseases. John Wiley & Sons, Inc 2024;61-72.

Crossref - Nyema J, Nath TC, Bhuiyan MJU, et al. Morpho-molecular investigation of ectoparasitic infestation of companion animals in Sylhet city, Bangladesh. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports. 2024;7:100953.

Crossref - Colella V, Nguyen VL, Tan DY, et al. Zoonotic Vectorborne Pathogens and Ectoparasites of Dogs and Cats in Eastern and Southeast Asia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020:26(6):1221-1233.

Crossref - Yanase T, Otsuka Y, Doi K, et al Other Medically Important Vectors. In: Sawabe, K., Sanjoba, C., Higa, Y. (eds) Medical Entomology in Asia. Entomology Monographs. Springer, Singapore. 2024.

Crossref - Fular A, Geeta, Nagar G, et al. Infestation of Ctenocephalides felis orientis and Ctenocephalides felis felis in human- a case report. Int J Trop Insect Sci. 2020;40(12):651-656.

Crossref - Zurita A, Benkacimi L, El Karkouri K, Cutillas C, Parola P, Laroche M. New records of bacteria in different species of fleas from France and Spain. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;76:101648.

Crossref - Rombot D, Pelealu J, Semuel MY. The diversity and composition of new pathogenic bacteria in cat fleas. Int J Pharm Res. 2021;13(2):2624-2633.

Crossref - Rombot DV, Mokosuli YS. The Metagenomic Analysis of Potential Pathogenic Emerging Bacteria in Fleas. Pak J Biol Sci. 2021;24(10):1084-1090.

Crossref - Rombot D, Semuel MY. Biochemical characteristics and antibiotic resistance of bacterial isolate from Ctenocephalides felis. J Phys Conf Ser. 2021;1968(1):012006.

Crossref - Zhang T, Wu Q, Zhang Z. Probable pangolin origin of SARS-CoV-2 associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr Biol. 2020;30(7):1346-1351.

Crossref - Qiu X, Liu Y, Sha A. SARS CoV 2 and natural infection in animals. J Med Virol. 2023;95(1):e28147.

Crossref - Stepani M, Duvnjak S, Reil I. et al. Epidemiology of Bartonella henselae infection in pet and stray cats in Croatia with risk factors analysis. Parasit Vectors. 2024;17:48.

Crossref - Moore C, Breitschwerdt EB, Kim L, et al. The association of host and vector characteristics with Ctenocephalides felis pathogen and endosymbiont infection. Front Microbiol. 2023;14;1137059.

Crossref - Barghash SM, Yassin SE, Sadek ASM, et al. Epidemiological exploration of fleas and molecular identification of flea-borne viruses in Egyptian small ruminants. Sci Rep. 2024;14:15166.

Crossref - Rampacci E, Trotta M, Fani C, et al. Comparative Performances of Vitek-2, Disk Diffusion, and Broth Microdilution for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Canine Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J Clin Microbio. 2021;159(9).

Crossref - Paluch M, Lleres-Vadeboin M, Poupet H, et al. Multicenter evaluation of rapid antimicrobial susceptibility testing by VITEK® 2 directly from positive blood culture. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023;106(3):115950.

Crossref - Torres-Sangiao E, Rodriguez BL, Pajaro MC, Montero RC, Pazos NP. Direct Urine Resistance Detection Using VITEK 2. Antibiotics. 2022;11(5):663.

Crossref - Rombot DV, Semuel MY, Kanan M. Bacterial Species Associate on the Body Surface of Musca domestica L from Various Habitats based on 16S rRNA Sequencing. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2023;17(3):1486-1494.

Crossref - Kanan M, Salaki C, Mokosuli YS. Molecular Identification of Bacterial species from Musca domesfica L. and Chrysomya megachepala L. Luwuk City, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2020;14(2):1595-1607.

Crossref - Ebani VV. Staphylococci, Reptiles, Amphibians, and Humans: What Are Their Relations? Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland). 2024;13(7):607.

Crossref - Thomson P, Garcia P, Miles J, et al. Isolation and Identification of Staphylococcus Species Obtained from Healthy Companion Animals and Humans. Vet Sci. 2022;9(2):79.

Crossref - Meservey A, Sullivan A, Wu C, Lantos PM. Staphylococcus sciuri peritonitis in a patient on peritoneal dialysis. Zoonoses Public Health. 2020;67(1):93-95.

Crossref - Algammal AM, Hetta HF, Elkelish A, et al. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): one health perspective approach to the bacterium epidemiology, virulence factors, antibiotic-resistance, and zoonotic impact. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:3255-3265.

Crossref - GOmez-Sanz E, Haro-Moreno JM, Jensen SO, Roda-GarcIa JJ, LOpez-PErez M. The resistome and mobilome of multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus sciuri C2865 unveil a transferable trimethoprim resistance gene, designated dfrE, spread unnoticed. Msystems. 2021;6(4):10-1128.

Crossref - Sands K, Carvalho MJ, Spiller OB, et al. Characterisation of Staphylococci species from neonatal blood cultures in low-and middle-income countries. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):593.

Crossref - Choudhury A, Vamadevan S, Parchani A, Kumar S, Gangadharan J, Bairwa M. A Rare Presentation of Ecthyma Gangrenosum-like Lesions due to Staphylococcus lentus in an Immunocompetent Adult: A Case Report. Indian J Crit Care Case Rep. 2023;2(4):85-87.

Crossref - Silva V, Alfarela C, Canica M, et al. A one health approach molecular analysis of Staphylococcus aureus reveals distinct lineages in isolates from Miranda donkeys (Equus asinus) and their handlers. Antibiotics. 2022;11:(3):374.

Crossref - Hay CY, Sherris DA. Staphylococcus lentus Sinusitis: A New Sinonasal Pathogen. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020;99(6):NP62-NP63.

Crossref - Rey Perez J, Zalama Rosa L, Garcia Sanchez A, et al. Multiple Antimicrobial Resistance in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus sciuri Group Isolates from Wild Ungulates in Spain. Antibiotics. 2021;10(8):920.

Crossref - Bahuaud O, Le Brun C, Lemaignen A. Host Immunity and Francisella tularensis: A Review of Tularemia in Immuno-compromised Patients. Microorganisms. 2021;9(12):2539.

Crossref - Kinkead LC, Krysa SJ and Allen L-AH. Neutrophil Survival Signaling During Francisella tularensis Infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:889290.

Crossref - Catanzaro KCF, Inzana TJ. The Francisella tularensis Polysaccharides: What Is the Real Capsule? Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2020;84:e00065-19.

Crossref - Degabriel M, Valeva S, Boisset S, Henry T. Pathogenicity and virulence of Francisella tularensis. Virulence. 2023;14(1):2274638.

Crossref - Chai Q, Wang L, Liu CH, Ge B. New insights into the evasion of host innate immunity by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:901-913.

Crossref - Han G, Zhang J, Luo Z, et al. Characteristics of a novel temperate bacteriophage against Staphylococcus arlettae (vB_SarS_BM31). Int Microbiol. 2023;26(2):327-341.

Crossref - Wong AHK, Lai GKK, Griffin SDJ, Leung FCC. Complete Genome Sequence of Staphylococcus arlettae AHKW2e, Isolated from a Dog’s Paws in Hong Kong. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2022;11(7):e00350-22.

Crossref - Rossi CC, Ahmad F, Giambiagi-deMarval, M. Staphylococcus haemolyticus: an updated review on nosocomial infections, antimicrobial resistance, virulence, genetic traits, and strategies for combating this emerging opportunistic pathogen. Microbiol Res. 2024;282:127652.

Crossref - Dier-Pereira AP, Thihara T, Duarte FC, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus haemolyticus displaying reduced susceptibility to vancomycin and high biofilm-forming ability. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2021;21(7):63-70.

Crossref - Lima LM, da Silva BNM, Barbosa G, Barreiro EJ. β-lactam antibiotics: An overview from a medicinal chemistry perspective. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;208:112829.

Crossref - Astore MA, Pradhan AS, Thiede EH, Hanson SM. Protein dynamics underlying allosteric regulation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2024;84:102768.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.