ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

In developing nations, neonatal sepsis is still a major leading health concern, especially with the increasing threat posed by antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and the prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms. The objective of this study is to examine the resistance patterns of antibiotics and assess the occurrence of multidrug-resistant organisms in neonatal sepsis cases at a tertiary care hospital in India. A cross-sectional observational study was conducted from July 2023 to February 2025 in the NICU of a tertiary care hospital. We included all neonates after 35 weeks of gestation with suspected sepsis admitted to the Department of Pediatrics, SGT Hospital. Neonates who had received antibiotics for more than 24 hours prior to admission were excluded. The sample size was calculated using the single population proportion formula, considering the prevalence of neonatal sepsis to be 20.7%. The calculated sample size was 253; however, we planned to enroll 300 neonates to obtain a round figure and ensure adequate representation. Blood specimens from 300 neonates presenting with clinical signs of sepsis were processed for culture using the automated BACTEC system. Bacterial isolates were characterized, and their antibiotic resistance profiles were determined following established standard procedures. Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel. Of 300 neonates, 68 (23%) had culture-confirmed sepsis. Gram-positive cocci (66.18%) were more prevalent than Gram-negative bacilli (33.82%). The predominant isolates included Coagulase-negative Staphylococci (61.36%), Klebsiella pneumoniae (34.78%), and Acinetobacter spp. (21.74%). Gram-positive isolates showed high resistance to erythromycin (44.44%) and penicillin (38.88%), while Gram-negative isolates demonstrated the highest resistance to ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and gentamicin (47.82% each). Multidrug-resistance was common, notably in Klebsiella pneumoniae (87.5%), Acinetobacter lwoffii (50%), Escherichia coli (50%), Staphylococcus saprophyticus (100%), and Streptococcus mitis (100%). The high prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms, especially among Gram-negative isolates, highlights an urgent need for strengthened antimicrobial stewardship through measures such as rational antibiotic use, periodic antibiotic susceptibility surveillance, and implementation of strict infection control practices including hand hygiene, aseptic procedures, and isolation of resistant cases. Continuous surveillance and rational antibiotic use are essential to mitigate the threat of AMR in neonatal care settings.

Antimicrobial Resistance, Gram-negative Bacilli, Gram-positive Cocci, Multidrug-resistance, Neonatal Sepsis, NICU

Neonatal sepsis is a serious health problem in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) around the world, particularly in developing countries, where it leads to high rates of complications and deaths. Nearly one-fourth of all newborn infection-related deaths occur in India alone. Neonatal sepsis poses a major hindrance to decreasing newborn death rates in resource-limited settings.1 Preterm

newborns and those with low birth weight are more vulnerable.2 The treatment of MDR bacterial infections poses a major challenge due to their resistance to several first-line antibiotics.3-5 As a consequence of limited therapeutic options, neonatal sepsis remains a major contributor to illness and death in newborns, even with antibiotic use.6

In 2023, around 2.3 million babies died within the first month of life worldwide-about 6,300 newborn deaths each day.7 From 1990 to 2023, the global neonatal mortality rate dropped by an average of 2.3% per year, which is slower compared to a 3.3% yearly decline among children aged 1 to 59 months.7 India’s share of global neonatal deaths decreased from 30.7% in 1990 to 17.6% in 2023.7 Despite this progress, neonatal infections remain a major contributor to mortality, and in limited-resource settings, treating infections caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria is even more challenging due to restricted availability of effective antibiotics.8

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) represents a significant global health concern, especially with the rise of multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), and pan-drug-resistant (PDR) bacterial strains. Mild resistance is defined as bacterial resistance to a single class of antimicrobial agents.9 Moderate resistance refers to resistance observed against two different antimicrobial classes. Multidrug-resistance (MDR) refers to the non-susceptibility of a microorganism to at least one drug in three or more distinct antibacterial agent classes. Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) organisms exhibit resistance to all but one or two antimicrobial categories, leaving only a few therapeutic options available. In contrast, PDR indicates resistance to all available antimicrobial agents, leaving no treatment options.9

In some cases, doctors need to use a combination of antibiotics, including carbapenems, to treat these infections.10 However, these strong antibiotics are not easily available in low-resource settings, and overusing them can lead to more resistance. This makes it vital to prevent MDR infections in newborns.8 Good hygiene practices, strong infection control in hospitals, wise use of antibiotics, timely diagnosis, and maintaining cleanliness in neonatal care units are all key steps in reducing the risk of such infections.6

In many low- and middle-income countries, Gram-negative bacilli and coagulase-negative Staphylococci (CoNS) are frequently implicated in neonatal sepsis. Conversely, in high-income settings, Group B Streptococcus (GBS), Escherichia coli, and Listeria monocytogenes are more commonly reported as primary pathogens.11 In the Indian context, the predominant organisms associated with neonatal sepsis include CoNS, Klebsiella spp., Acinetobacter spp., and E. coli.12 The effective management of these infections is particularly challenging in resource-limited regions due to constraints such as inadequate diagnostic infrastructure, poor implementation of infection control practices, and the absence of robust antibiotic stewardship policies.13 These challenges often result in delayed or inappropriate therapy, contributing to increased neonatal morbidity and mortality. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to assess the antibiotic resistance patterns and prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms among neonatal sepsis cases in a tertiary care hospital.

Over the course of three years, a cross-sectional observational study was conducted in a hospital in the Department of Microbiology, in collaboration with the Department of Paediatrics, at a tertiary care teaching hospital. The study received ethical clearance from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC). In this study, a total of 300 (≥35 weeks gestation) neonates were enrolled. Neonates who had received antibiotics for more than 24 hours prior to admission were excluded. Sepsis was categorized as culture-positive or probable (based on ≥2 abnormal lab parameters), and further classified as early-onset (≤72 hours) or late-onset (>72 hours). Trained nursing staff collected venous blood samples from neonates admitted to the NICU who were clinically suspected of having sepsis, for the purpose of blood culture and other sepsis-related investigations. Enrolment was done following the receipt of informed consent from parents or guardians, and each infant was observed throughout their hospital stay until discharge or death. During enrolment and follow-up, data on various factors-including demographic details, neonatal and maternal risk factors, clinical symptoms, laboratory findings, microbiological results, and antimicrobial treatments-were recorded using case report forms (CRFs).

Blood cultures were processed using the BacT/ALERT 3D system, with positive samples subcultured and identified by standard methods and confirmed with the VITEK 2 Compact ID/AST system. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing followed CLSI M100, 33rd Edition (2023) guidelines. The Hi-PCR 16S rRNA SYBR PCR Kit was used to identify Gram-positive cocci (GPC) and Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) based on DNA extracted from bacterial samples for molecular confirmation.

Statistical analysis

For data entry and analysis, Microsoft Excel 2016 was used. Descriptive statistics, including tables and graphs, were utilized to present the distribution of bacterial isolates and their corresponding antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiles.

The study enrolled a total of 300 neonates, including 171 males (57.0%) and 129 females (43.0%). Among them, 68 cases (23%) were confirmed to have sepsis based on positive blood culture results. The majority of cases (83.0%) presented within the first three days of life, while 17.0% were aged four days or older. Clinical and demographic association with culture positivity which was significantly higher among neonates shown in Table 1. The identified variables showed a significant association with an elevated risk of neonatal sepsis.

Table (1):

Clinical and demographic correlates of positive bacterial blood cultures in neonates evaluated for sepsis

| Variables | Category | Blood culture result | Total | Pearson χ2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative n = 232 (%) | Positive n = 68 (%) | |||||

| Gestational age at Birth | <37 GA | 137 | 57 | 194 | 14.123 | <0.001 |

| ≥37 GA | 95 | 11 | 106 | |||

| Weight at birth | <2500 g (LBW) | 141 | 36 | 177 | 1.334 | 0.003 |

| >2500 g (Normal) | 91 | 32 | 123 | |||

| Mode of delivery | Vaginal delivery | 171 | 51 | 222 | 0.046 | 0.024 |

| Caesarean section | 61 | 17 | 78 | |||

| Type of sepsis | Early onset (≤72 hours) | 203 | 46 | 249 | 14.689 | <0.001 |

| Late onset (>72 hours) | 29 | 22 | 51 | |||

| Premature rupture of membranes | Yes <18 h | 11 | 21 | 139 | 32.119 | <0.001 |

| Yes >18 h | 848 | 38 | 86 | |||

| No | 66 | 09 | 75 | |||

Among the 300 suspected cases, 249 (83.0%) were identified as EOS and 51 (17.0%) as LOS.

The occurrence of culture proven neonatal sepsis was 68 (23%). Among the 68 culture-positive cases, Gram-positive cocci (n = 45, 66.18%) were more commonly isolated than Gram-negative bacilli (n = 23, 33.82%) (Table 2).

Table (2):

Distribution of Bacterial Isolates Identified from Neonatal Sepsis Cases (n = 68)

| Bacterial Isolates | Frequency (n = 68) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive (n = 45) | ||

| • Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus aureus (CoNS) | 27 | 61.36 |

| • Staphylococcus aureus | 4 | 9.09 |

| • Staphylococcus hominis | 3 | 6.82 |

| • Staphylococcus epidermis | 3 | 6.82 |

| • Enterococcus spp. | 3 | 6.82 |

| • Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 2 | 4.55 |

| • Staphylococcus saprophyticus | 1 | 2.27 |

| • Enterococcas fecalis | 1 | 2.27 |

| • Streptococcus mitis | 1 | 2.27 |

| Gram-negative (n = 23) | ||

| • Klebsiella pneumoniae | 8 | 34.78 |

| • Acinetobacter baumanni | 5 | 21.74 |

| • Acinetobacter loffii | 2 | 8.7 |

| • Enterobacter cloacae | 2 | 8.7 |

| • Escherichia coli | 2 | 8.7 |

| • Burkholderia cepacia | 1 | 4.35 |

| • Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 | 4.35 |

| • Pseudomonas stutzeri | 1 | 4.35 |

| • Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 | 4.35 |

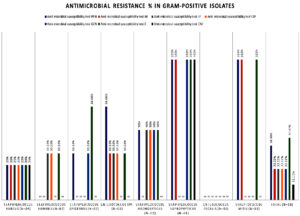

The antimicrobial resistance profile of Gram-positive bacterial isolates (n = 18) from suspected neonatal sepsis cases showed the highest resistance to erythromycin (44.44%) and penicillin (38.88%). Moderate resistance was observed for levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and minocycline (22.22% each), while chloramphenicol resistance remained low (11.11%). Multidrug-resistance was predominantly seen in Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and Enterococcus spp. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Antimicrobial susceptibility test result showing resistance for Gram-positive bacterial pathogens isolated from suspected of neonatal sepsis

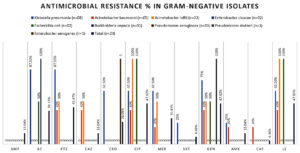

For Gram-negative isolates (n = 23), the highest resistance was noted against ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and gentamicin (47.82% each). Moderate resistance levels were detected for amoxicillin-clavulanate (39.13%), meropenem (30.43%), and ceftriaxone (26.08%). Resistance to ampicillin-sulbactam and amikacin was relatively low (13.04%), and the lowest was for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (8.69%) and chloramphenicol (4.34%). Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter spp. demonstrated significant multidrug-resistance (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Antimicrobial susceptibility test results resistance for Gram-negative bacterial isolates from suspected of neonatal sepsis

Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial isolates demonstrated multidrug- resistance (MDR). Among Gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus saprophyticus and Streptococcus mitis showed 100% MDR, while Staphylococcus aureus, S. haemolyticus, Enterococcus spp., S. hominis, and S. epidermidis exhibited MDR rates ranging from 33.3% to 50%. Among Gram-negative isolates, Klebsiella pneumoniae had the highest MDR rate (87.5%), followed by Acinetobacter lwoffii and Escherichia coli (50% each). Other isolates, including Enterobacter cloacae, Burkholderia cepacia, Pseudomonas spp., and Enterobacter aerogenes, showed minimal or no MDR.

In the present study, blood cultures identified etiologic agents in 23% of neonates with suspected sepsis. This detection rate falls within the global range of 6.7%-55.4% and aligns moderately with previous Indian studies reporting positivity between 33% and 64%.14-17 Lower rates observed in studies by Jatsho et al.18 Gupta and Kashyap,19 and Ansari et al.20 may reflect differences in methodology. The use of an automated system (BD BACTEC) in our study likely enhanced detection sensitivity compared to manual systems used in earlier research.21 Additionally, the high proportion of coagulase-negative Staphylococci (CoNS) isolates (61.36%) which may represent true infections or, in some cases, potential contaminants-could have contributed to increased culture positivity. The predominance of Gram-positive cocci in EOS cases in our study may be attributed to intrapartum antibiotic use and variations in local epidemiological patterns.

Gram-positive isolates exhibited high resistance to erythromycin (44.44%) and penicillin (38.88%), consistent with global and regional patterns of β-lactamase-mediated resistance.22 Chloramphenicol showed the highest efficacy (88.88%), followed by minocycline, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and gentamicin (77.77% each). These findings are in agreement with data from a tertiary care center in Tamil Nadu, where similar susceptibility patterns were observed.22

Among Gram-negative isolates, chloramphenicol remained the most effective agent (95.65%), followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (91.3%), and ampicillin-sulbactam, ceftazidime, and amikacin (87% each). In contrast, levofloxacin showed reduced sensitivity (69.56%), likely due to widespread use and resistance mechanisms such as efflux pumps and target mutations. Notably, Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae exhibited reduced sensitivity to β-lactam agents, suggesting the presence of ESBL or carbapenemase activity. This finding aligns with a study by Garg and Usha, who reported high susceptibility of Gram-negative isolates to chloramphenicol (84%) and amikacin (68%).23 Alarmingly, K. pneumoniae demonstrated resistance to amoxiclav and piperacillin-tazobactam (87.5%), and 62.5% resistance to ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, and meropenem, corroborating the trends observed by Marwah et al.24

Despite rising resistance, 90% of neonates in this study were managed empirically with ampicillin and gentamicin. The prevalence of MDR pathogens, particularly S. aureus and K. pneumoniae, raises clinical concern. Similar resistance burdens have been documented by Jain, who reported MDR in 84.3% of K. pneumoniae and 57.1% of S. aureus isolates.1 Additionally, Gashaw highlighted S. aureus as a predominant neonatal sepsis pathogen, with 57.1% methicillin resistance and widespread resistance among K. pneumoniae strains.26 Studies from North India also report high MDR rates among Gram-negative isolates.25,26 These findings underscore the urgent need for continuous antimicrobial resistance surveillance and robust antibiotic stewardship programs to guide empirical therapy and curb the spread of MDR organisms in neonatal intensive care units.

Neonatal sepsis remains a significant clinical and public health concern, particularly in developing countries, due to its high morbidity and mortality among vulnerable neonates. Early detection and efficient treatment of sepsis remain difficult despite improvements in neonatal care, largely due to its nonspecific presentation and rising antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotic susceptibility patterns suggest that while agents like chloramphenicol and aminoglycosides retain efficacy, resistance to routinely used antibiotics remains a critical concern. These findings call for judicious use of antimicrobials and the implementation of robust antibiotic stewardship programs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the laboratory staff of the Department of Microbiology and the Central Molecular Laboratory (especially Mr. Ajay and Mr Amit), as well as the nursing staff of the NICU, for their invaluable support in helping us achieve the required sample size. The authors are also sincerely grateful to SGT Hospital and SGT University for their support and for providing the necessary facilities to conduct this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of SGT University and Hospital, Budhera, Gurugram, India.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants before enrolling in the study.

- Jain K, Kumar V, Plakkal N, et al. Multidrug-resistant sepsis in special newborn care units in five district hospitals in India: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2025;13(5):E870–E878.

Crossref - Wattal C, Kler N, Oberoi JK, Fursule A, Kumar A, Thakur A. Neonatal sepsis: mortality and morbidity in neonatal sepsis due to multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms: part 1. Indian J Pediatr. 2020;87:117-121.

Crossref - Perez-Palacios P, Girlich D, Soraa N, et al. Multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales responsible for septicaemia in a neonatal intensive care unit in Morocco. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2023;33:208-217.

Crossref - Wu X, Wang C, He L, et al. Clinical characteristics and antibiotic resistance profile of invasive MRSA infections in newborn inpatients:a retrospective multicenter study from China. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23(1):264.

Crossref - Readman J, Acman M, Hamawandi A, et al. Cefotaxime/sulbactam plus gentamicin as a potential carbapenem- and amikacin-sparing first-line combination for neonatal sepsis in high ESBL prevalence settings. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2023;78(8):1882-1890.

Crossref - Rallis D, Giapros V, Serbis A, Kosmeri C, Baltogianni M. Fighting antimicrobial resistance in neonatal intensive care units:rational use of antibiotics in neonatal sepsis. Antibiotics. 2023;12(3):508.

Crossref - UNICEF. Neonatal mortality [Internet]. Available from:https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/neonatal-mortality. Accessed 2025 May 30.

- Gashaw M, Ali S, Berhane M, et al. Neonatal sepsis due to multidrug-resistant bacteria at a tertiary teaching hospital in Ethiopia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2024;43(7):687-693.

Crossref - Walana W, Vicar EK, Kuugbee ED, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of clinical bacterial isolates according to the WHO’s AWaRe and the ECDC-MDR classifications:the pattern in Ghana’s Bono East Region. Front Antibiotics. 2023;2:1291046.

Crossref - Rizvi MQ, Singh MV, Mishra N, Shrivastava A, Maurya M, Siddiqui SA. Intravenous immunoglobulin in the management of neonatal sepsis:a randomised controlled trial. Trop Doct. 2023;53(2):222-226.

Crossref - Shah NS, Srivastava R, Mehta T, Shah A, Chandwani C. Study of etiological profile, risk factors and immediate outcome of neonatal sepsis. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2025;12(5):755-762.

Crossref - Panigrahi P, Chandel DS, Hansen NI, et al. Neonatal sepsis in rural India:timing, microbiology, and antibiotic resistance in a population-based prospective study in the community setting. J Perinatol. 2017;37(8):911–921.

Crossref - Toan ND, Darton TC, Boinett CJ, et al. Clinical features, antimicrobial susceptibility patterns and genomics of bacteria causing neonatal sepsis in a children’s hospital in Vietnam:protocol for a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e019611.

Crossref - Devkota K, Kanodia P, Joshi B. Sepsis among neonates admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit in a tertiary care centre. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2024;62(270):76-78.

Crossref - Berhane M, Gidi NW, Eshetu B, et al. Clinical profile of neonates admitted with sepsis to neonatal intensive care unit of Jimma Medical Center, a tertiary hospital in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2021;31(3):485-494.

Crossref - Sethi K, Verma RK, Yadav RK, Singh DP, Singh S. A study on bacteriological profile in suspected cases of neonatal sepsis and its correlation with various biomarkers in the rural population of a university hospital. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2023;12(10):2313-2317.

Crossref - NNPD Network. National neonatal-perinatal database (report 2002–2003). New Delhi: Department of Pediatrics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences;2005. Accessed on 06 May 2025. https://www.newbornwhocc.org/pdf/nnpd_report_2002-03.pdf

- Jatsho J, Nishizawa Y, Pelzom D, Sharma R. Clinical and bacteriological profile of neonatal sepsis:a prospective hospital based study. Int J Pediatr. 2020;2020(1):1835945.

Crossref - Khanal LK. Bacteriological profile of blood culture and antibiogram of the bacterial isolates in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Health Sci Res. 2020;10(8):10-4

- Ansari S, Nepal HP, Gautam R, Shrestha S, Neopane P, Chapagain ML. Neonatal septicemia in Nepal:early-onset versus late-onset. Int J Pediatr. 2015;2015(1):379806.

Crossref - Ahmad A, Iram S, Hussain S, et al. Diagnosis of paediatric sepsis by automated blood culture system and conventional blood culture. Yeast. 2017;5(3).

- Dasari SN, Raja JA, Kumar KS, Jothi DS. Bacterial profiles and their antibiotic susceptibility patterns in neonatal sepsis at tertiary care hospital Tamil Nadu:a retrospective study. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2024;31(11):802-812.

Crossref - Garg P, Usha MG. A study of neonatal septicaemia in a tertiary care hospital. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2018;12(1):369-374.

Crossref - Marwah P, Chawla D, Chander J, Guglani V, Marwah A. Bacteriological profile of neonatal sepsis in a tertiary-care hospital of Northern India. Indian Pediatr. 2015;52(2):158-159.

- Jajoo M, Manchanda V, Chaurasia S, et al. Alarming rates of antimicrobial resistance and fungal sepsis in outborn neonates in North India. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0180705.

Crossref - Investigators of the Delhi Neonatal Infection Study (DeNIS) collaboration. Characterisation and antimicrobial resistance of sepsis pathogens in neonates born in tertiary care centres in Delhi, India:a cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(10):e752–60.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.