ISSN: 0973-7510

E-ISSN: 2581-690X

This study aimed to assess bacterial co-infections in patients diagnosed with positive COVID-19 with respiratory dysfunction and severe pneumonia symptoms admitted in intensive care unit (ICU) of tertiary care hospital. This research was an observational study performed on 166 clinical bacterial isolates obtained from sputum, blood, urine of 20 critically ill COVID-19 positive patients diagnosed by RT PCR technique. Pathogens included were 82 Gram-negative and 84 Gram-positive clinical isolates. Antibiotic susceptibility was determined by broth MIC method. Among Gram-negative organisms, carbapenem resistance was found to be 54.55%, 33.33%, 93.33% in Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, respectively. Cefepime/zidebactam was found to be most active antibacterial agent tested. In Gram-positive isolates S. aureus and Enterococcus sp. were the most encountered isolates. Against Enterococcus sp. linezolid, daptomycin, vancomycin, tigecycline showed 100% susceptibility. For S. aureus, levonadifloxacin (WCK 771) was found to be most active antibiotic with 100% susceptibility followed by linezolid, teicoplanin. Presence of β-lactamases was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaNDM, blaCMY, blaOXA-48-like. In E. coli, NDM was most encountered β-lactamase whereas in K. pneumoniae, ESBL were predominantly detected. Dual carbapenemase i.e. NDM and OXA-48 like observed in K. pneumoniae. Most of the P. aeruginosa showed presence of OXA-4 and VEB type β-lactamase presence. Study clearly demonstrated early determination of co-infections and need of developing targeted antibacterial therapy as the highest priority. Findings showed presence of β-lactamases in bacterial pathogens that render the antibiotic resistant characteristics which significantly affect the clinical outcome and recovery of COVID-19 positive patients. Hence, it has become an urgent need to discover new antibiotics.

COVID-19, ICU, Antibiotic, Resistance, β-lactamases, Bacterial Coinfections, Susceptibility, Comorbidity, Mortality

In December 2019, formerly unidentified microbial agents leading to respiratory tract infections were observed in patients in Wuhan, China. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a novel β-coronavirus, was reported as the causative pathogen and WHO termed the disease as COVID-19.1,2 Patients with COVID-19 positive results need admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) due to the wide spectrum of clinical complications of the disease from mild infection to respiratory failure. Even though global vaccination lead to the decrease in mortality rate, milder disease with newly emerged variants, and improvement in therapeutic options, high risk patients may still require admission in ICU admission.3 During initial months of COVID-19 pandemic, mortality rate in ICU was reported to be found between 30%-50% depending on the mechanical ventilation, level of the ICU, and study populations. Older age, diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, oncologic, hematologic malignancy, interstitial lung disease, and secondary bacterial infections are the main risk factors of mortality among the patients with COVID-19 being treated in ICU.4,5

Secondary bacterial infections leading to mortality in ICUs has been understood as one of the leading causes. Duration of intubation, status, catheter insertion and duration of ICU stay are the main attributes of secondary bacterial infections. In addition, use of corticosteroids and anti-cytokine medicines negatively impact immunity results in development of secondary infections. Consequently, respiratory viral infections including influenza with secondary bacterial infections is a well-known issue; however, their role in COVID-19 still has uncertainties and complicated.6,7 The rate of secondary bacterial infection was recorded to be 8.1% (ranging from 0%-25%) among ICU patients in a meta-analysis. This study was performed with the aim to determine the impact of secondary bacterial infections on mortality rate in the ICU and to investigate the etiology of secondary bacterial infections in COVID-19 as a result of their attributable effects, as compared to non-COVID-19 patients.8,9

In last three years, the world has been hit by two major COVID-19 pandemic waves. The first wave of pandemic led to overall low fatality rates and ICU admissions. However, during the second wave, the disease was often complicated owing to significantly elevated severity of infections, thereby leading to ICU admissions.10 In the COVID-19 pneumonia during second wave, highest fatality rates were encountered. It was observed that, the concurrence of bacterial infection in COVID-19 positive patients was also an important factor associated with mortality and severity of infection. A study reported the disease, with its clinical presentation including cough, fever, and lung infiltrates, resembles bacterial pneumonia in the subset of COVID-19 patients admitted to hospitals.11-13

It has been reported that, a scenario of 3.5% and 28% secondary bacterial infections were observed in ICU admitted COVID-19 patients. The pathogens involved in these bacterial infections were Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae being the most common isolates observed that the incidence of ICU-acquired bacterial infection was as high as 51.2%. The respiratory infections were 38.5% predominant, followed by complicated urinary tract infections (28.0%) and blood stream infections (30.7%).14-17

Another study reported that, bacterial infections were present in both non-COVID-19 (1001) and COVID-19 (1398) and patients (13% vs. 8%). Mostly nosocomial infections were reported in COVID-19 patients whereas patients with negative COVID-19 had community acquired infections. The severity of infections in patients with COVID-19 was found to be 81% which was also significant based on chest X-ray with higher bilateral infiltrates as compared to 48% in non-COVID-19 patients. Mortality rate was higher in patients with COVID-19 bacterial pneumonia compared to non-COVID-19 patients (15% vs. 9% respectively).18-20

In a survey comprising of 166 participants from 23 countries and 82 different hospitals, clinical presentation was recognized as the most important reason for the start of antibiotics. When antibiotics were started, most respondents rated as the highest the need for coverage of Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa. Combination of fluoroquinolones and β-lactams was often deployed for the treatment of these pathogens. It is known about the piperacillin/tazobactam as the most preferred prescribed antibiotic for the patients admitted in the ICU. The mean duration of antibiotic treatment was reported to be 7.12 (SD = 2.44) days.21-23

In past, several studies showed the role of bacterial co-infection in COVID-19 pneumonia patients and the impact on clinical outcome. However, limited data is available assessing the frequency, identification of pathogens, resistance mechanisms expressed and impact of antibiotic therapies in predicting the clinical outcome in COVID-19 positive patients. This will help in determining the COVID-19 associated bacterial infections and help evolve treatment guidelines and identify the unmet need in treating bacterial infections in such patients.24-30

Hence, aim of this study was to evaluate the secondary bacterial infections and investigate their antibiotic resistance characteristics in COVID-19 positive patients admitted to ICUs. The present study also focused to determine the correlation of resistance mechanisms expressed by bacterial pathogens, antibiotic therapy used and clinical outcome in terms of mortality.

Patient inclusion criteria

The patients admitted in ICU of 500 bedded tertiary care MGM Medical College and Hospital in Chhatrapati. Sambhajinagar, with confirmed infection of COVID-19 (RT-PCR positive and hRCT score of >6) were enrolled for the study. Experimental work of this project includes antibiotic susceptibility testing and identification of β-lactamases using PCR method was performed in central research laboratory, MGM Medical College and Hospital in Chhatrapati. Sambhajinagar. Proposed research work was carried out strictly in accordance with the ethical guidelines prescribed by Central Ethics Committee on Human Research (CECHR). The details of the proposed departmental research work were also discussed and approved by MGM-ECRHS Institutional Ethics Committee.

Bacterial isolates and susceptibility testing

The microbiological assessments were done on day 3, 7 and 14. Total n = 166 non-duplicate isolates were recovered from twenty COVID-19 patients. The bacterial identification was done using biochemical method and MALDI-TOF based identification was performed for all isolates. The antibiotic susceptibility of various antibiotics was determined against all the isolates according to CLSI guidelines. In addition, recently approved antibiotics such as ceftazidime/avibactam, imipenem/relebactam, ceftolozane/tazobactam and levonadifloxacin and antibiotic under phase III clinical trial cefepime/zidebactam, were also evaluated.

The commercial formulations were used for MIC testing. Zidebactam, tazobactam, levonadifloxacin, ceftolozane, relebactam, avibactam were provided by Wockhardt Research Center, India.

The susceptibilities of bacterial isolates were interpreted using CLSI breakpoints (for levonadifloxacin package insert based and for cefepime/zidebactam PK/PD based susceptibility criteria was used.

β-lactamase identification

β-lactamase genes of blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaNDM, blaCMY, blaOXA-48-like were amplified with PCR method using appropriate primers described previously.

Demography of patients

Twenty critically ill patients admitted in ICU were enrolled in the present study. They include 17 male and 3 female patients. Median age of participants was 59 ± 12.3 years. Comorbidities were present in 50% patients. The demographic descriptive analysis was presented in Table 1.

Table (1):

Descriptive analysis of demographic characteristics, comorbidities in patients with secondary respiratory tract infection among COVID-19 positive patients

Patient ID |

Gender |

Age (Years) |

Comorbidities |

Length of stay in ICU (Days) |

End status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

P1 |

M |

69 |

Diabetes Mellitus |

10 |

Deceased |

P2 |

M |

60 |

None |

21 |

Survived |

P3 |

M |

55 |

None |

19 |

Survived |

P4 |

M |

57 |

None |

17 |

Deceased |

P5 |

M |

47 |

Diabetes Mellitus and Hypertension |

7 |

Survived |

P6 |

M |

31 |

None |

8 |

Survived |

P7 |

M |

57 |

Diabetes Mellitus |

8 |

Survived |

P8 |

M |

56 |

Interstitial Lung disease |

9 |

Deceased |

P9 |

M |

67 |

Diabetes Mellitus and Hypertension |

33 |

Deceased |

P10 |

M |

70 |

None |

10 |

Deceased |

P11 |

M |

53 |

Hypertension |

6 |

Survived |

P12 |

M |

67 |

Coronary Artery disease (CAD) |

1 |

Survived |

P13 |

F |

71 |

None |

7 |

Survived |

P14 |

F |

65 |

None |

17 |

Deceased |

P15 |

M |

74 |

None |

11 |

Survived |

P16 |

M |

74 |

Diabetes Mellitus, Hypertension |

12 |

Survived |

P17 |

M |

58 |

None |

22 |

Deceased |

P18 |

M |

35 |

Diabetes Mellitus |

6 |

Survived |

P19 |

F |

70 |

Hypertension |

9 |

Deceased |

P20 |

M |

40 |

None |

10 |

Survived |

Median |

59 ± 12.3 |

10 ± 7.2 |

Bacterial isolates

Total 166 bacterial isolates were recovered from the sputum, blood and urine samples on various assessment days. The organisms included 82 Gram-negative and 84 Gram-positive isolates. Among Gram-negative isolates, K. pneumoniae was encountered the most followed by E. coli, P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter sp. complex. While among Gram-positive isolates, Enterococci sp. was encountered the most followed by S. aureus and Streptococcus parasanguinis. The complete description of bacterial isolates is provided in Table 2.

Table (2):

Bacterial isolates recovered from various samples from COVID-19 positive patients

Organism |

Sputum |

Blood |

Urine |

|---|---|---|---|

K. pneumoniae |

21 |

1 |

|

E. coli |

14 |

2 |

|

Pseudomonas sp. |

11 |

||

Acinetobacter sp. |

10 |

||

A. baumannii |

7 |

||

Burkholderia cenocepacia |

2 |

||

Chryseobacterium gleum |

2 |

||

E. cloacae |

2 |

||

Enterobacter |

1 |

1 |

|

Pluralibacter gergoviae |

2 |

||

Chryseobacterium indologenes |

1 |

||

Elizabethkingia anophelis |

1 |

2 |

|

Stenotrophomonas |

1 |

||

Citrobacter amalonaticus |

1 |

||

Enterococci |

22 |

1 |

4 |

Staphylococcus aureus |

16 |

5 |

2 |

S. epidermidis |

1 |

||

S. parasanguinis |

10 |

||

S. mitis/oralis |

6 |

||

S. pneumoniae |

3 |

||

Streptococci mittis |

3 |

||

Streptococci sp. |

2 |

||

Granulicatella adiacens |

2 |

||

Lysinibacillus fusiformis |

2 |

2 |

|

Abiotrophia deftiva |

1 |

||

Enterococci faecalis |

1 |

||

Rothia mucilaginosa |

1 |

||

Total |

145 |

12 |

9 |

Antibacterial agents used for treatment

COVID-positive patients with suspected bacterial infections were prescribed antibacterial agents based on symptoms. Ceftriaxone was the most prescribed antibiotic followed by meropenem, piperacillin/tazobactam and colistin. Among newly approved agents ceftazidime/avibactam and levonadifloxacin were prescribed to five and one patient respectively. Detailed description of antibiotic prescription is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Clinical outcomes

The overall mortality was 40.0% (08/20). The comorbidities among survived and deceased and the mortality was similar (50.0%) in patients with and without comorbidities. There was no associated higher mortality with diabetes, hypertension of coronary artery disease presented in Table S2.

Antibiotic susceptibility

Antibiotic susceptibility was determined by broth MIC method using CLSI guidelines. Among Gram-negative organisms carbapenem resistance was 54.55%, 33.33% and 93.33% in Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii respectively. Cefepime/zidebactam was the most active antibacterial agent tested as shown in Table 3.

Table (3):

Antibiotic susceptibility (%) for Gram-negative bacterial isolates recovered from COVID-19 positive patients

| Antibiotic | Susceptibility (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Enterobacterales (N = 33) | Pseudomonas (N = 9) | Acinetobacter sp. (N = 15) | |

| Cefepime | 27.27 | 88 | 26.67 |

| Cefepime/zidebactam* | 100 | 100 | 66.67 |

| Ceftazidime | 15.15 | 66.67 | 6.67 |

| Ceftazidime/avibactam | 48.48 | 88.88 | NT |

| Colistin | NA | NA | NA |

| Imipenem | 45.45 | 66.67 | 13.33 |

| Meropenem | 45.45 | 77.78 | 6.67 |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 33.33 | 88.88 | 25 |

| Aztreonam/avibactam# | 87.88 | 100 | NT |

| Amikacin | 45.45 | 100 | 33.33 |

*Cefepime/zidebactam tested in 1:1 ratio as per CLSI, PK/PD based breakpoints were used

#aztreonam/avibactam current breakpoint of aztreonam was applied

NA – breakpoint are not available, NT – not tested

In Gram-positive isolates S. aureus and Enterococcus sp. were the most encountered isolates. Against Enterococcus sp. linezolid, daptomycin, vancomycin and tigecycline showed 100% susceptibility. While for S. aureus levonadifloxacin (WCK 771) was the most active antibiotic with 100% susceptibility followed by linezolid and teicoplanin as shown in Table 4.

Table (4):

Antibiotic percentage susceptibility for Gram-positive Enterococci sp. and Staphylococci sp. isolates recovered from COVID-19 positive patients

| Antibiotic | Susceptibility (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Staphylococci (n = 21) | Enterococci (n = 21) | |

| Linezolid | 95.24 | 100 |

| Daptomycin | NT | 100 |

| Vancomycin | 100 | 100 |

| Levofloxacin | 42.86 | 38.81 |

| Ampicillin | NT | 66.67 |

| Tigecycline | NT | 100 |

| Synercid | NT | 38.81 |

| WCK 771 (Levonadifloxacin) | 100 | 38.81 |

| Teicoplanin | 95.24 | NT |

| Cefoxitin | 23.81 | NT |

| Minocycline | 80.95 | NT |

| Clindamycin | 66.67 | NT |

Only one S. epidermidis was isolated and it was found to be susceptible to vancomycin, minocycline, linezolid, clindamycin, and was resistant to cefoxitin and WCK 771

Against Streptococcus sp. clindamycin was the most active agent followed by nafithromycin, whereas solithromycin and levofloxacin showed limited activity. Among Streptococcus sp. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid susceptibility was observed among 50% isolates whereas penicillin was 100% non-susceptible against Streptococci sp. as shown in Table 5.

Table (5):

Antibiotic percentage susceptibility for Gram-positive Streptococci sp. isolates recovered from COVID-19 positive patients

| Antibiotic | Susceptibility (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| S. pneumoniae (n = 4) | S. mitis/oralis (n = 7) | S. parasanguinis (10) | |

| Azithromycin | 25 | 14.28 | 10 |

| Clindamycin | 100 | 85.72 | 80 |

| WCK 4873 (Nafithromycin) | 100 | 85.72 | 40 |

| Solithromycin | 100 | 28.56 | 40 |

| Levofloxacin | 100 | 28.56 | 50 |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 50 | 0 | 50 |

| Penicillin-G | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| WCK 771 | 100 | 42.84 | 50 |

β-lactamase in Gram-negative isolates

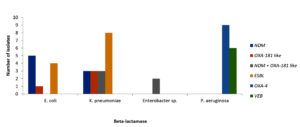

The presence of β-lactamases was confirmed by performing polymerase chain reaction for blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, blaNDM, blaCMY, blaOXA-48-like. In E. coli NDM was the most encountered β-lactamase whereas in K. pneumoniae ESBL were predominant. Dual carbapenemases i.e. NDM and OXA-48 like were observed in K. pneumoniae. All A.baumannii isolates showed the presence of OXA 23 and OXA 58, including three showed the presence of NDM as well in Table 6 and Figure. Most of the P. aeruginosa showed presence of OXA-4 and VEB type β-lactamase presence as shown in Table 7 and Figure.

Table (6):

Activity of recently approved/pipeline and older antibiotics against Acinetobacter spp. (n = 11) recovered from COVID-19 positive patients

| Acinetobacter IDs | β-lactamases | MIC (mg/L) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEP | FEP-ZID 1:1 | IPM | IPM+4234-4 | SUL | ||

| MGM-16 | OXA-23, OXA-58 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0.25 | 4 |

| MGM-19 | OXA-23, OXA-58 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0.5 | 8 |

| MGM-21 | OXA-23, OXA-58 | 16 | 4 | 16 | 32 | >128 |

| MGM-32 | OXA-58 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.5 | 128 |

| MGM-21 | OXA-23, OXA-58 | 128 | 32 | 128 | 32 | 64 |

| MGM-87 | OXA-23, OXA-58 | >128 | 32 | >128 | 128 | 128 |

| MGM-115 | OXA-23, OXA-58 | >128 | 32 | >128 | 128 | 128 |

| MGM-113 | NDM, OXA-23, OXA-58 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 128 |

| MGM-160 | NDM, OXA-23, OXA-58 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 128 |

| MGM-161 | OXA-23, OXA-58 | 128 | 64 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| MGM-162 | NDM, OXA-23, OXA-58 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | 128 |

FEP : Cefepime; ZID : Zidebactam ; IPM: imipenem; WCK4234: a potent class D (OXA carbapenemase) β-lactamase inhibitor; SUL: sulbactam

Table (7):

Activity of recently approved/pipeline and older antibiotics against P. aeruginosa (n = 9) recovered from COVID-19 positive patients

| P. aeruginosa IDs | β-lactamases | MIC (mg/L) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEP | FEP/ZID 1:1 | CAZ | CAZ/ AVI | CST | IPM | IPM/REL | MEM | PIP/TAZ | AMK | ||

| MGM-4 | OXA-4, VEB | 64 | 1 | >128 | >128 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | >128 | 8 |

| MGM-15 | OXA-4 | 64 | 4 | >128 | 16 | 0.5 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 | >128 |

| MGM-27 | OXA-4, VEB | 8 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 32 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| MGM-95 | OXA-4, VEB | 2 | 0.25 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 8 | >64 | 16 | 2 | 1 |

| MGM-98 | OXA4, OXA-2, VEB | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 4 |

| MGM-125 | OXA4, OXA-2, VEB | 4 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 8 | 4 |

| MGM-137 | OXA-4, VEB | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 16 | 2 |

| MGM-145 | OXA-4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 8 | 2 |

| MGM-71 | OXA-4, VEB | 16 | 0.25 | >64 | 4 | 0.5 | 16 | 32 | 1 | >64 | 2 |

FEP: cefepime; ZID: zidebactam; CAZ: ceftazidime; AVI: avibactam; CST: colistin; IPM: imipenem; REL: relebactam; MEM: meropenem; PIP/TAZ: piperacillin/tazobactam; AMK: amikacin

A viral pneumonia with an unusual outbreak, COVID-19 was considered as major health concern and accountable for 7 million deaths worldwide. In addition to COVID-19, bacteria and fungi are reported to cause Coinfections in critically ill patients, which increase its morbidity and mortality. In an observational study of COVID-positive patients, 58.8% bacterial culture positive rates were reported by Shiralizadeh et al.5

In present study median stay in ICU was 10 ± 7 days; undoubtedly this duration for bacteria was an excellent opportunity to infect the patients. Furthermore, sampling was done multiple times to evaluate the bacterial coinfection in the patients, which resulted in increased culture positivity rates. With emphasis on secondary bacterial infection of the COVID-positive patients, among Gram-negative isolates, K. pneumoniae (13.25%) was the most common organism followed by A. baumannii complex (10.24%). Similar observation was reported from Turkiye and Wuhan in two independent retrospective studies conducted during 2020 and 2022 by Stoian et al1 and Chen et al.2 In Gram-positive isolates Enterococcus (16.26%) and S. aureus (13.85%) were most frequently encountered.

Infection with E. coli, S. aureus and A. baumannii was observed significantly higher percentage in deceased patients. It was confirmed in a study performed by Liu et al. that the co-infection of extensively antibiotic-resistant A. baumannii and avian influenza A virus in the patients with invasive mechanical ventilation is a key factor for the high mortality and severity of the disease.3 It was note withstanding that only one antibiotic was prescribed to all the discharged patients whereas more than two antibiotics were prescribed for patients who died. This clearly indicates currently available antibacterial therapy against MDR pathogens is inadequate and more specifically infection caused by β-lactamase producing pathogen the treatment decisions have become scarce and thus multiple amalgamations were used in the anticipation of cure. Nevertheless β-lactamases such as blaNDM, blaOXA_48 like either alone or in combinations shows increasing trends in India among Enterobacterales. In case of Acinetobacter baumannii blaNDM, blaOXA_23 presents the toughest treatment challenge.

The study clearly demonstrated early determination of co-infection and the need to develop targeted antibacterial therapy as the highest priority. Findings showed significance of presence of potential β-lactamases in bacterial pathogens that render the antibiotic-resistant characteristics which significantly affect the clinical outcome and recovery of COVID-19 positive patients.

Moreover, there is an urgent need to discover and develop new antibiotics as an unmet medical need to reduce the burden of infectious diseases, which can tackle the bacterial infections caused by β-lactamase producing organisms.

Clinical outcomes and significance

The overall mortality was 40.0% (08/20). The comorbidities among survived and deceased and the mortality was similar (50.0%) in patients with and without comorbidities. There was no associated higher mortality with diabetes, hypertension of coronary artery disease presented in Table S2.

Additional file: Table S1-S2.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful to the MGM trust for providing the necessary and dedicated research laboratory facilities within MGM Medical College and Hospital to perform experimental work. The authors are thankful to the Department of Pharmacy, Birla Institute of Technology and Sciences (BITS) Pilani, for their collaborative support for intellectual inputs. Authors are very much thankful to Wockhardt Ltd. for providing the antibiotics- Zidebactam, tazobactam, levonadifloxacin, ceftolozane, relebactam, and avibactam as gift samples for this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

FUNDING

None.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All datasets generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and/or in the supplementary files.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, MGM Medical College and Hospital, (Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar) Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India, vide identification number as MGM-ECRHS/2020/01.

INFORMED CONSENT

Written informed consents were obtained from participating patients before enrolling them into the study.

- Stoian M, Azamfirei L, Andone A, et al. Incidence and Risk Factors of Secondary Infections in Critically Ill SARS-CoV-2 Patients: A Retrospective Study in an Intensive Care Unit. Biomedicines. 2025;13(6):1333.

Crossref - Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507-513.

Crossref - Singh A, Tanwar M, Singh TP, Sharma S, Sharma P. Unveiling Natural Power: Morin and Myricetin as Potent Inhibitors of Histidinol-Phosphate Aminotransferase in Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. ACS Omega. 2025;10(8):7920-7936.

Crossref - Areta ML, Valiton A, Diana A, et al. Flu and pertussis vaccination during pregnancy in Geneva during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multicentric, prospective, survey-based study. Vaccine. 2022;40(25):3455-3460.

Crossref - Shiralizadeh S, Azimzadeh M, Keramat F, et al. Investigating the Prevalence of Bacterial Infections in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 Hospitalized in Intensive Care Unit and Determining their Antibiotic Resistance Patterns. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2025;25(4):e18715265338445.

Crossref - Randolph AG, Xu R, Novak T, Newhams MM, et al. Vancomycin Monotherapy May Be Insufficient to Treat Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Coinfection in Children With Influenza-related Critical Illness. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(3):365-372.

Crossref - Hedayati-Ch M, Ebrahim-Saraie HS, Bakhshi A. Clinical and immunological comparison of COVID-19 disease between critical and non-critical courses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1341168.

Crossref - Hanna JJ, Most ZM, Cooper LN, et al. Mortality in hospitalized SARS-CoV-2 patients with contemporaneous bacterial and fungal infections. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2024;4(1):e142.

Crossref - Panda B, Singh N, Singh G, et al. RT-PCR Result of SARS-CoV-2 Viral RNA in Cadavers and Viral Transmission Risk to Handlers. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2024;28(6):614-616.

Crossref - Jiang L, Jin Y, Li J, et al. Respiratory Pathogen Coinfection During Intersecting COVID-19 and Influenza Epidemics. Pathogens. 2024;13(12):1113.

Crossref - Doubravska L, Htoutou MS, Fiserova K, et al. Bacterial Community- and Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia in Patients with Critical COVID-19: A Prospective Monocentric Cohort Study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2024;13(2):192.

Crossref - Jeong JH, Heo M, Park S, et al. Association between Age-Adjusted Endothelial Activation and Stress Index and Intensive Care Unit Mortality in Patients with Severe COVID-19. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2024;87(4):524-531.

Crossref - Wu HY, Chang PH, Huang YS, et al. Recommendations and guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) associated bacterial and fungal infections in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2023;56(2):207-235.

Crossref - Murgia F, Fiamma M, Serra S, et al. The impact of secondary infections in COVID-19 critically ill patients. J Infect. 2022;84(6):e116-e117.

Crossref - Fazel P, Sedighian H, Behzadi E, et al. Interaction Between SARS-CoV-2 and Pathogenic Bacteria. Curr Microbiol. 2023;24;80(7):223.

Crossref - Antuori A, Gimenez M, Linares G, Cardona PJ. Characterization of respiratory bacterial co-infection and assessment of empirical antibiotic treatment in patients with COVID-19 at hospital admission. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):19302.

Crossref - Sannathimmappa MB, Marimuthu Y, Al Subhi SMMS, et al. Incidence of secondary bacterial infections and risk factors for in-hospital mortality among coronavirus disease 2019 subjects admitted to secondary care hospital: A single-center cross-sectional retrospective study. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2024;14(2):94-100.

Crossref - Masuda S, Jinushi R, Imamura Y, et al. Association of short-course antimicrobial therapy and bacterial resistance in acute cholangitis: Retrospective cohort study. Endosc Int Open. 2024;12(2):E307-E316.

Crossref - Rawson TM, Wilson RC, Holmes A. Understanding the role of bacterial and fungal infection in COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(1):9-11.

Crossref - Chagas ALD, Araujo JCDS, Serra JCP, et al. Co-Infection of SARS-CoV-2 and Klebsiella pneumoniae: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14(11):1149.

Crossref - Lakbar I, Delamarre L, Curtel F, et al. Antimicrobial Stewardship during COVID-19 Outbreak: A Retrospective Analysis of Antibiotic Prescriptions in the ICU across COVID-19 Waves. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(11):1517.

Crossref - Yang S, Hua M, Liu X, et al. Bacterial and fungal Coinfections among COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit. Microbes Infect. 2021;23(4-5):104806.

Crossref - Suleiman AS, Islam MA, Akter MS, Amin MR, Werkneh AA, Bhattacharya P. A meta-meta-analysis of co-infection, secondary infections, and antimicrobial resistance in COVID-19 patients. J Infect Public Health. 2023;16(10):1562-1590.

Crossref - Al-Ali AY, Salam A, Almuslim O, Alayouny M, Alhabib M, AlQadheeb N. Bacterial Superinfections in Critically Ill Patients With SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Intensive Care Med. 2025;40(4):447-455.

Crossref - Romanelli F, Stolfa S, Ronga L, et al. Coinfections in intensive care units. Has anything changed with Covid-19 pandemia? Acta Biomed. 2023;14;94(3):e2023075.

Crossref - Boia ER, Hut AR, Roi A, et al. Associated Bacterial Coinfections in COVID-19-Positive Patients. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(10):1858.

Crossref - Pawlak M, Lewtak K, Nitsch-Osuch A. Effectiveness of Antiepidemic Measures Aimed to Reduce Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in the Hospital Environment. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2022;2022:9299258.

Crossref - Kassem AB, Al Meslamani AZ, Elmaghraby DH, et al. The pharmacists’ interventions after a Drug and Therapeutics Committee (DTC) establishment during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2024;17(1):2372040.

Crossref - Papic I, Bistrovic P, Cikara T, et al. Corticosteroid Dosing Level, Incidence and Profile of Bacterial Blood Stream Infections in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Viruses. 2024;16(1):86.

Crossref - Siddiqui SS, Chatterjee S, Yadav A, et al. Cytomegalovirus Coinfection in Critically Ill Patients with Novel Coronavirus-2019 Disease: Pathogens or Spectators? Indian J Crit Care Med. 2022;26(3):376-380.

Crossref

© The Author(s) 2025. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.